Reenacting Operation Market Garden in Theirs Is the Glory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LEPT Study Tour Amsterdam, Arnhem, Rotterdam 12-14 May 2019

Facilitating Electric Vehicle Uptake LEPT study tour Amsterdam, Arnhem, Rotterdam 12-14 May 2019 1 Background Organising the study tour The London European Partnership for Transport (LEPT) has sat within the London Councils Transport and Mobility team since 2006. LEPT’s function is to coordinate, disseminate and help promote the sustainable transport and mobility agenda for London and London boroughs in Europe. LEPT works with the 33 London boroughs and TfL to build upon European knowledge and best practice, helping cities to work together to deliver specific transport policies and initiatives, and providing better value to London. In the context of a wider strategy to deliver cleaner air and reduce the impact of road transport on Londoners’ health, one of London Councils’ pledges to Londoners is the upscaling of infrastructures dedicated to electric vehicles (EVs), to facili- tate their uptake. As part of its mission to support boroughs in delivering this pledge and the Mayor’s Transport Strategy, LEPT organised a study tour in May 2019 to allow borough officers to travel to the Netherlands to understand the factors that led the country’s cities to be among the world leaders in providing EV infrastructure. Eight funded positions were available for borough officers working on electric vehicles to join. Representatives from seven boroughs and one sub-regional partnership joined the tour as well as two officers from LEPT and an officer that worked closely on EV charging infrastructure from the London Councils Transport Policy team (Appendix 1). London boroughs London’s air pollution is shortening lives and improving air quality in the city is a priority for the London boroughs. -

DIN 2019DIN01-014: Selection Process And

Defence Instructions and Notices (Not to be communicated to anyone outside HM Service without authority) Title: Selection Process and Service with Pathfinders (PF), 16 Air Assault Brigade’s Advance Force Audience: All Service Personnel Applies: Immediately Expires: When rescinded or replaced Replaces: 2015DIN01-207 Reference: 2019DIN01-014 Status: Current Released: January 2019 Channel: 01 Personnel Content: Information about service in Pathfinders, including the Application and Selection process. PF is a Tri Service unit. Sponsor: Pathfinders 16X Contact: xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx Keywords: Pathfinders; Pathfinder; Advance Force; Course Dates; Selection; PF; Local PFPC, PFSC Keywords: Supplements: N/A (Please click on the links to access >>>> ) Related Info: Classification: OFFICIAL Background 1. The Pathfinders (PF) were formally established in 1985 having existed in various forms as far back as 1942. They provide the Advance Force (AF) to facilitate Theatre Entry and subsequently form a Long Range Reconnaissance Patrol (LRRP) capability working direct to 16 Air Assault Brigade (16X) HQ. PF are a small unit who are constantly at very high readiness as part of the Air Assault Task Force (AATF). General 2. PF are currently based in Merville Barracks, Colchester and applications to join are accepted from soldiers and officers from all three services and all cap badges and trades. Within each PF patrol there exists a range of specialist skills including Forward Air Controllers, Snipers, Demolitionists and Medics. In addition all soldiers are trained in HAHO and HALO parachuting, Heavy Weapons, Mobility and SERE. Operating as an AF requires high calibre soldiers and officers who are well motivated, mentally and physically robust, reliable, determined and capable of working at significant distances from supporting forces. -

Film Club Sky 328 Newsletter Freesat 306 FEB/MAR 2021 Virgin 445

Freeview 81 Film Club Sky 328 newsletter Freesat 306 FEB/MAR 2021 Virgin 445 You can always call us V 0808 178 8212 Or 01923 290555 Dear Supporters of Film and TV History, It’s been really heart-warming to read all your lovely letters and emails of support about what Talking Pictures TV has meant to you during lockdown, it means so very much to us here in the projectionist’s box, thank you. So nice to feel we have helped so many of you in some small way. Spring is on the horizon, thank goodness, and hopefully better times ahead for us all! This month we are delighted to release the charming filmThe Angel Who Pawned Her Harp, the perfect tonic, starring Felix Aylmer & Diane Cilento, beautifully restored, with optional subtitles plus London locations in and around Islington such as Upper Street, Liverpool Road and the Regent’s Canal. We also have music from The Shadows, dearly missed Peter Vaughan’s brilliant book; the John Betjeman Collection for lovers of English architecture, a special DVD sale from our friends at Strawberry, British Pathé’s 1950 A Year to Remember, a special price on our box set of Together and the crossword is back! Also a brilliant book and CD set for fans of Skiffle and – (drum roll) – The Talking Pictures TV Limited Edition Baseball Cap is finally here – hand made in England! And much, much more. Talking Pictures TV continues to bring you brilliant premieres including our new Saturday Morning Pictures, 9am to 12 midday every Saturday. Other films to look forward to this month include Theirs is the Glory, 21 Days with Vivien Leigh & Laurence Olivier, Anthony Asquith’s Fanny By Gaslight, The Spanish Gardener with Dirk Bogarde, Nijinsky with Alan Bates, Woman Hater with Stewart Granger and Edwige Feuillère,Traveller’s Joy with Googie Withers, The Colour of Money with Paul Newman and Tom Cruise and Dangerous Davies, The Last Detective with Bernard Cribbins. -

During the Month of September, the 504Th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82Nd Airborne Division, Commemorates the WWII Events That

During the month of September, the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division, commemorates the WWII events that occurred during OPERATION MARKET GARDEN in 1944. On September 15tn, word came down for a proposed jump ahead of Gen. Dempsey’s British Second Army. The mission called for the Airborne Army to descend from the skies and occupy bridges over the extensive waterways of Southern and Central Holland. The 504th, jumping as part of the 82nd Airborne Division, was to descend 57 miles behind enemy lines in the vincity of Grave, Holand and take the longest span bridge in Europe over the Maas River, along with two other bridges over the Maas-Waal Canal. At 1231, pathfinder men of the 504th landed on the DZ and thus became the first Allied troops to land in Holland; 34 minutes later the regiment “hit the silk” and the greatest airborne invasion in history was officially on The 2nd BN, 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR), was given the mission to take the bridge over the Maas River. E Company of the 2nd BN, 504th was to jump south of the Maas River while the remainder of the 2nd BN would descend north of the river. The Hero of this article is 1LT John Thompson, who was 27 years old and the Platoon Leader of 3rd Platoon E Company, 2nd BN, 504th PIR . His mission was to take the southern end of the grave bridge over the Maas River. At fifteen hundred feet long, with nine spans, the bridge was the largest and most modern in all of Europe. -

Title: Study Visit Energy Transition in Arnhem Nijmegen City Region And

Title: Study Visit Energy Transition in Arnhem Nijmegen City Region and the Cleantech Region Together with the Province of Gelderland and the AER, ERRIN Members Arnhem Nijmegen City Region and the Cleantech Region are organising a study visit on the energy transition in Gelderland (NL) to share and learn from each other’s experiences. Originally, the study visit was planned for October 31st-November 2nd 2017 but has now been rescheduled for April 17-19 2018. All ERRIN members are invited to participate and can find the new programme and registration form online. In order to ensure that as many regions benefit as possible, we kindly ask that delegations are limited to a maximum of 3 persons per region since there is a maximum of 20 spots available for the whole visit. Multistakeholder collaboration The main focus of the study visit, which will be organised in cooperation with other interregional networks, will be the Gelders’ Energy agreement (GEA). This collaboration between local and regional industries, governments and NGOs’ in the province of Gelderland, Netherlands, has pledged for the province to become energy-neutral by 2050. It facilitates a co-creative process where initiatives, actors, and energy are integrated into society. a A bottom-up approach The unique nature of the GEA resides in its origin. The initiative sprouted from society when it faced the complex, intricate problems of the energy transition. The three initiators were GNMF, the Gelders’ environmental protection association, het Klimaatverbond, a national climate association and Alliander, an energy network company. While the provincial government endorses the project, it is not a top-down initiative. -

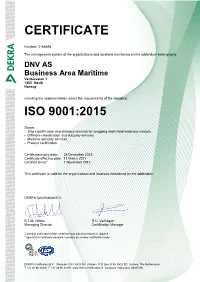

ISO 9001 Certificate

CERTIFICATE Number: 2166898 The management system of the organizations and locations mentioned on the addendum belonging to: DNV AS Business Area Maritime Veritasveien 1 1363 Høvik Norway including the implementation meets the requirements of the standard: ISO 9001:2015 Scope: - Ship classification and statutory services for seagoing and inland waterway vessels - Offshore classification and statutory services - Maritime advisory services - Product certification Certificate expiry date: 28 December 2023 Certificate effective date: 11 March 2021 Certified since*: 1 November 2013 This certificate is valid for the organizations and locations mentioned on the addendum. DEKRA Certification B.V. j E B.T.M. Holtus R.C. Verhagen Managing Director Certification Manager © Integral publication of this certificate and adjoining reports is allowed * against this certifiable standard / possibly by another certification body DEKRA Certification B.V. Meander 1051, 6825 MJ Arnhem P.O. Box 5185, 6802 ED Arnhem, The Netherlands T +31 88 96 83000 F +31 88 96 83100 www.dekra-certification.nl Company registration 09085396 page 1 of 13 ADDENDUM To certificate: 2166898 The management system of the organizations and locations of: DNV AS Business Area Maritime Veritasveien 1 1363 Høvik Norway Certified organizations and locations: DNV GL Angola Serviços Limitada DNV GL Argentina S.A Belas Business Park, Etapa V, Avenida Leandro N. Alem 790, 9th andar, Torre Cuanza Sul, Piso 6 – CABA, Talatona, Luanda Buenos Aires - C1001AAP Angola Argentina DNV GL Australia Pty -

WESTERTERP CV.Pdf

CURRICULUM VITAE Professor Klaas R Westerterp Education MSc Biology, University of Groningen, The Netherlands, 1971. Thesis: The energy budget of the nestling Starling Sturnus vulgaris: a field study. Ardea 61: 127-158, 1973. PhD University of Groningen, The Netherlands, 1976. Thesis: How rats economize – energy loss in starvation. Physiol Zool 50: 331-362, 1977. Professional employment record 1966-1971 Teaching assistant, Animal physiology, University of Groningen 1968-1971 Research assistant, Institute for Ecological Research, Royal Academy of Sciences, Arnhem 1971 Lecturer, Department of Animal Physiology, University of Groningen 1976 Lecturer, Department of Animal Ecology, University of Groningen 1977 Postdoctoral research fellow, University of Stirling, Scotland 1980 Postdoc, Animal Ecology, University of Groningen and Royal Academy of Sciences, Arnhem 1982 Senior lecturer, Department of Human Biology, Maastricht University 1998 Visiting professor, KU Leuven, Belgium 2001 Professor of Human Energetics, Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University Research The focus of my work is on physical activity and body weight regulation, where physical activity is measured with accelerometers for body movement registration and as physical activity energy expenditure, under confined conditions in a respiration chamber and free-living with the doubly labelled water method. Management, advisory and editorial board functions Head of the department of Human Biology (1999-2005); PhD dean faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences (2007- 2011); member of the FAO/WHO/UNU expert group on human energy requirements (2001); advisor Philips Research (2006-2011); advisor Medtronic (2006-2007); editor in chief Proceedings of the Nutrition Society (2009-2012); editor in chief European Journal of Applied Physiology (2012-present). -

British Cinema of the 1950S: a Celebration

A Tale of Two Cities and the Cold War robert giddings There was probably never a book by a great humorist, and an artist so prolific in the conception of character, with so little humour and so few rememberable figures. Its merits lie elsewhere. (John Forster, The Life of Charles Dickens (1872)) R T’ A Tale of Two Cities of 1958 occupies a secure if modest place among that bunch of 1950s British releases based on novels by Dickens, including Brian Desmond Hurst’s Scrooge (1951) and Noel Langley’s The Pickwick Papers (1952).1 When all the arguments about successfully filming Dickens are considered it must be conceded that his fiction offers significant qualities that appeal to film-makers: strong and contrasting characters, fascinating plots and frequent confrontations and collisions of personality. In unsuspected ways, Ralph Thomas’s film is indeed one of the best film versions of a Dickens novel and part of this rests upon the fact that, as Dickens’s novels go, A Tale of Two Cities is unusual. Dickens elaborately works up material in this novel which must have been marinating in his imagination. Two themes stand out: the dual personality, the doppelgänger or alter ego; and mob behaviour when public order collapses. Several strands come together. Dickens had voluminously researched the Gordon Riots which were, up to then, the worst public riots in British history. Charles Mackay’s Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds (1845) I am Professor Emeritus in the School of Media Arts, Bournemouth Univer- sity. My schooling was interrupted by polio, but I was very well educated by wireless, cinema and second-hand books. -

Militairen in De Collectieve Herinnering Aan De Slag Om

MILITAIREN IN DE COLLECTIEVE HERINNERING AAN DE SLAG OM ARNHEM Een onderzoek naar de aandacht voor Britse gewonden en krijgsgevangenen en hun functie in het discours. Naam: Pim Gerritzen Studentnummer: 4516540 Studie: BA-Geschiedenis Instituut: Radboud Universiteit Plaats: Nijmegen Begeleider: Dr. Joost Rosendaal Datum: 15-6-2018 Inhoudsopgave Inleiding ................................................................................................................................................... 3 Status Quaestionis ............................................................................................................................... 4 Omgang met militairen in Nederland .............................................................................................. 4 Omgang met militairen in Groot-Brittannië .................................................................................... 6 Vraagstelling ........................................................................................................................................ 7 Methode .............................................................................................................................................. 8 1. De Slag om Arnhem en de functie van militairen .............................................................................. 11 1.1 De Slag om Arnhem en het voortleven in de collectieve herinnering ........................................ 11 1.2 De functie van militairen in het verhaal ..................................................................................... -

Download (2631Kb)

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/58603 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. A Special Relationship: The British Empire in British and American Cinema, 1930-1960 Sara Rose Johnstone For Doctorate of Philosophy in Film and Television Studies University of Warwick Film and Television Studies April 2013 ii Contents List of figures iii Acknowledgments iv Declaration v Thesis Abstract vi Introduction: Imperial Film Scholarship: A Critical Review 1 1. The Jewel in the Crown in Cinema of the 1930s 34 2. The Dark Continent: The Screen Representation of Colonial Africa in the 1930s 65 3. Wartime Imperialism, Reinventing the Empire 107 4. Post-Colonial India in the New World Order 151 5. Modern Africa according to Hollywood and British Filmmakers 185 6. Hollywood, Britain and the IRA 218 Conclusion 255 Filmography 261 Bibliography 265 iii Figures 2.1 Wee Willie Winkie and Susannah of the Mounties Press Book Adverts 52 3.1 Argentinian poster, American poster, Hungarian poster and British poster for Sanders of the River 86 3.2 Paul Robeson and Elizabeth Welch arriving in Africa in Song of Freedom 92 3.3 Cedric Hardwicke and un-credited actor in Stanley and Livingstone -

FM 3-21.38 Pathfinder Operations

FM 3-21.38 Pathfinder Operations APRIL 2006 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. Headquarters Department of the Army This publication is available at Army Knowledge Online (www.us.army.mil) and General Dennis J. Reimer Training and Doctrine Digital Library at (www.train.army.mil). *FM 3-21.38 Field Manual Headquarters No. 3-21.38 Department of the Army Washington, DC, 25 April 2006 Pathfinder Operations Contents Page PREFACE............................................................................................................................................ viii Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................................1-1 Employment .........................................................................................................1-1 Capabilities...........................................................................................................1-2 Limitations ............................................................................................................1-2 Equipment ............................................................................................................1-2 Communications Security ....................................................................................1-5 Training ................................................................................................................1-5 Chapter 2 PLANS, ORGANIZATION, CONDUCT, AND THREAT...........................................2-1 -

Renown Pictures New Dvd Release Includes Everything on These Two Pages

Freeview 81 Film Club Sky 328 newsletter Freesat 306 MAY/JUNE 2021 Virgin 445 You can always call us V 0808 178 8212 Or 01923 290555 Dear Supporters of Film and TV History, At last, we can finally announce that tickets are now on sale for our 8th Festival of Film/ Road Show on Sunday 10th October 2021, 11am-7pm at the iconic Plaza, Stockport. We also have a special event planned on Saturday 9th at the beautiful Savoy Cinema, just around the corner at Heaton Moor. The Savoy is very much like ‘The Bijou’ from The Smallest Show on Earth, (without all the problems!), so we decided to hold a proper Saturday Morning Pictures Show on Saturday 9th October 2021 from 9am-12pm – bring your pop guns and wear your badges! There will be a special guest and a separate Film Quiz with Afternoon Tea in the afternoon from 1-4pm. It will be a smaller event than The Plaza on the Sunday so get your tickets quick! There’s not many seats available at The Savoy. If you have specific seating requests for ANY EVENT, then call us to book your tickets rather than online or on the order form. When booked we will send you a fact sheet on parking and hotels etc. Exciting times – we’ve got some great guests lined up for this year! For those of you who have tickets already from last year – we will post out your new packs as soon as we can. More details on pages 26-28. At last we can all have a get together to look forward to! This month there’s something very special for Gracie Fields fans, a limited edition necklace with her autograph, and TWO DVDs for just £20.