Revised Sixth National Development Plan Final Evaluation Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sister Brigid Gallagher Feast of St

.- The story of the Sisters of the Sacred Hearts of )> Jesus and Mary in Zambia Brigid Gallagher { l (Bemba: to comfort, to cradle) The story of the Sisters of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary in Zambia 1956-2006 Sisters of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary Let us praise illustrious people, our ancestors in their successive generations ... whose good works have not been forgotten, and whose names live on for all generations. Book of Ecclesiasticus, 44:1, 1 First published in the United Kingdom in 2014 by Sisters of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary Text© 2014 Sisters of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary ISBN 978-0-99295480-2 Production, cover design and page layout by Nick Snode ([email protected]) Cover image by Michael Smith (dreamstime.com) Typeset in Palatino 12.5/14.Spt Printed and bound by www.printondemand-worldwide.com, Peterborough, UK Contents Foreword ................................... 5 To th.e reader ................................... 6 Mother Antonia ................................ 7 Chapter 1 Blazing the Trail .................... 9 Chapter 2 Preparing the Way ................. 19 Chapter 3 Making History .................... 24 Chapter4 Into Africa ......................... 32 Chapters 'Ladies in White' - Getting Started ... 42 Chapter6 Historic Events ..................... 47 Chapter 7 'A Greater Sacrifice' ................. 52 Bishop Adolph Furstenberg ..................... 55 Chapter 8 The Winds of Change ............... 62 Map of Zambia ................................ 68 Chapter 9 Eventful Years ..................... 69 Chapter 10 On the Edge of a New Era ........... 79 Chapter 11 'Energy and resourcefulness' ........ 88 Chapter 12 Exploring New Ways ............... 96 Chapter 13 Reading the Signs of the Times ...... 108 Chapter 14 Handing Over .................... 119 Chapter 15 Racing towards the Finish ......... -

FORM #3 Grants Solicitation and Management Quarterly

FORM #3 Grants Solicitation and Management Quarterly Progress Report Grantee Name: Maternal and Child Survival Program Grant Number: # AID-OAA-A-14-00028 Primary contact person regarding this report: Mira Thompson ([email protected]) Reporting for the quarter Period: Year 3, Quarter 1 (October –December 2018) 1. Briefly describe any significant highlights/accomplishments that took place during this reporting period. Please limit your comments to a maximum of 4 to 6 sentences. During this reporting period, MCSP Zambia: Supported MOH to conduct a data quality assessment to identify and address data quality gaps that some districts have been recording due to inability to correctly interpret data elements in HMIS tools. Some districts lacked the revised registers as well. Collected data on Phase 2 of the TA study looking at the acceptability, level of influence, and results of MCSP’s TA model that supports the G2G granting mechanism. Data collection included interviews with 53 MOH staff from 4 provinces, 20 districts and 20 health facilities. Supported 16 districts in mentorship and service quality assessment (SQA) to support planning and decision-making. In the period under review, MCSP established that multidisciplinary mentorship teams in 10 districts in Luapula Province were functional. Continued with the eIMCI/EPI course orientation in all Provinces. By the end of the quarter under review, in Muchinga 26 HCWs had completed the course, increasing the number of HCWs who improved EPI knowledge and can manage children using IMNCI Guidelines. In Southern Province, 19 mentors from 4 districts were oriented through the electronic EPI/IMNCI interactive learning and had the software installed on their computers. -

MAIN REPORT Mapping of Health Links in the Zambian

Tropical Health and Education Trust Ministry of Health UNITED KINGDOM ZAMBIA MAIN REPORT Mapping of Health Links in the Zambian Health Services and Associated Academic Institutions under the Ministry of Health Submitted to: The Executive Director Tropical Health and Education Trust (THET) 210 Euston Road, London NW1 2BE UNITED KINGDOM and The Permanent Secretary Ministry of Health Ndeke House, Haile Selassie Avenue PO Box 30205, Lusaka ZAMBIA August 2007 CAN Investments Limited 26 Wusakili Crescent, Northmead PO Box 39485, Lusaka, Zambia Tel/Fax: 260-1-230418, E-mail: [email protected] MAIN REPORT The Tropical Health and Education Trust Mapping of Health Links in the Zambian Health In conjunction with Services and Associated Academic Institutions The Ministry of Health of Zambia under the Ministry of Health CONTENTS PAGE ACRONYMS USED...................................................................................................................................III FOREWORD AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.......................................................................................V 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..................................................................................................................1 1.1 INTRODUCTION..............................................................................................................................1 1.2 METHODOLOGY AND APPROACH ..................................................................................................1 1.3 EXISTING HEALTH LINKS ..............................................................................................................1 -

Consultancy Services for Techno Studies, Detailed Engineering

Consultancy Services for Techno Studies, Detailed Engineering Design and Preparation of THE REPUBLIC Tender Documents for the Rehabilitation of the OF ZAMBIA AFRICAN Chinsali-Nakonde Road (T2) DEVELOPMENT Draft ESIA Report BANK Consultancy Services for Techno Studies, Detailed Engineering Design and Preparation of Tender Documents for the Rehabilitation of the Chinsali-Nakonde Road (T2) Draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) Issue No: 01 First Date of Issue: January 2015 Second Date of Issue: February 2015 Prepared by: Chamfya Moses Quality Control: Chansa Davies Approved: Mushinge Renatus i Consultancy Services for Techno Studies, Detailed Engineering Design and Preparation of THE REPUBLIC Tender Documents for the Rehabilitation of the OF ZAMBIA AFRICAN Chinsali-Nakonde Road (T2) DEVELOPMENT Draft ESIA Report BANK DECLARATION: DEVELOPER I, , on behalf of the Road Development Agency of Zambia, hereby submit this Draft Environmental and Social Impact Statement for the proposed rehabilitation of the 210Km T2 Road from Chinsali to Nakonde Roads in accordance with the Environmental Management Act 2011 and the Environmental Impact Assessment Regulations S.I. No. 28 of 1997. Signed at LUSAKA on this day of , 2015 Signature: Designation: ROAD DEVELOPMENT AGENCY DECLARATION: CONSULTING ENGINEER I, , on behalf of BICON (Z) Ltd, hereby submit this Draft Environmental and Social Impact Statement for the proposed rehabilitation of the 210Km T2 Road from Chinsali to Nakonde Road in accordance with the Environmental Management Act 2011 and the -

District 413 Zambia Directory

LIONSLIONSLIONS CLUBSCLUBSCLUBS INTERNATIONALINTERNATIONALINTERNATIONAL DISTRICTDISTRICTDISTRICT 413413413 -- ZAMBIAZAMBIAZAMBIA DISTRICTDISTRICT DIRECTORYDIRECTORY 20182018 -- 1919 are rich in heritage and pride The International Association of Lions Clubs began as the dream of Chicago businessman Melvin Jones.. He believed that local business clubs should expand their horizons from purely professional concerns to the betterment of their communities and the world at large.. Today, our “We Serve” motto continues, represented by more volunteers in more places than any other service club organization in the world. We are friends, neighbors and leaders ready to help our communities grow and thrive.. Melvin Jones lionsclubs.org For information on a club in your area contact: [email protected] Our mission is to empower volunteers to serve their communities, meet humanitarian needs, encourage peace and promote international understanding through Lions clubs. Contents Distict Governor’s Message 1 International President’s Message 2 International President’s Office 3 ISAAME Secretariat 4 District Governor’s Office 5 Global Action Team 7 Council of Past District Governors 8 Region Chairpersons 11 Zone Chairpersons 12 District Committee Chairpersons 15 Leo District 24 Leo District President’s Office 25 District Clubs 26 Melvin Jones Fellows 39 Loyal Toasts 44 Lions Code of Ethics 45 Lions Clubs International Purposes 46 Past District Governors 47 Lions Funeral service / Necrology 48 DISTRICT 413 GOVERNOR DR. GEORGE SM BANDA As Lions how can we build on our already impressive legacy? It's simple, we will do what Lions have always done. We will get creative and reach within our communities, clubs and selves to discover a new level of service. -

Overall Grant Program Title

FORM #3 Grants Solicitation and Management Quarterly Progress Report Grantee Name: Maternal and Child Survival Program Grant Number: # AID-OAA-A-14- 00028 Primary contact person regarding this report: Mira Thompson ([email protected]) Reporting for the quarter Period: Year 2, Quarter 4 (July to September 2018) 1. Briefly describe any significant highlights/accomplishments that took place during this reporting period. Please limit your comments to a maximum of 4 to 6 sentences. • Following the gaps that were identified during the routine TA visits to the districts in the first and second quarters, MCSP engaged the districts in the supported provinces in revising their 2018 annual workplans and budgets based on the data (scorecards) and service quality assessment (SQA) findings. Using these tools, MCSP influenced the inclusion of appropriate high-impact interventions (HIIs) to respond to identified gaps in the revised workplans and recommended the allocation of resources in an equitable manner. Consequently, Districts revised the 2018 CoC plans to incorporate these recommendations and identified interventions that would be included in the 2019 plans in all provinces. Additional details are provided in the provincial report annexes. • MCSP provided technical assistance (TA) during the provincial integrated management meeting (PIM) across all of the four target provinces. These meetings provided an opportunity for MCSP to identify areas requiring TA in a context-specific and responsive manner to the needs of each district. MCSP contributed to discussions in those meetings by making on-the-spot recommendations for improving specific indicators. For example, using a very brief role play, MCSP graphically showed districts a simple way of estimating the number of new FP acceptors. -

Download Tariff Book 2012.Pdf

PREAMBLE The third edition of the Tanzania Zambia Railway Authority (TAZARA) Official Tariff Book contains Regulations, Condition and Charges worked out in accordance with the provisions of the Tanzania Zambia Railway Authority Act, 1995 This edition effective, 1st January 2012 is for the guidance of employees charged with the responsibility of ensuring that TAZARA offers a world class railway transport service within and between East, Central and Southern Africa as promulgated in its Vision and Mission statements. MANAGING DIRECTOR 1 TANZANIA ZAMBIA RAILWAY AUTHORITY HEAD OFFICE (DAR ES SALAAM) MANAGING DIRECTOR P.O. BOX 2834 DAR ES SALAAM Telephone: +255 222860380/4 Fax: +255 22 2865192/ +255 0748 771417 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.tazarasite.com REGIONAL OFFICES Regional General Manager (T) Area of operations - P.O. BOX 40160 Dar-es-Salaam Port to Tunduma DAR ES SALAAM Telephone: +255 222864992 Fax: +255 222864992 E-mail: [email protected] Regional General Manager (Z) Area of operations - P.O. BOX T01 New Kapiri-Mposhi to Nakonde MPIKA Telephone: +260 4370684/ +260 4370228 Fax: +260 4370228 E-mail: [email protected] BUSINESS CONTACTS Marketing Manager P.O. BOX 2834 Dar es Salaam Telephone +255 222862412 E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] Head Commercial (T) P.O. BOX 40160 Dar es Salaam Telephone +255 222863265 E-mail: [email protected] Head Commercial (Z) P.O. BOX 810036 Kapiri Mposhi Telephone +260 5271148 E-mail: [email protected] Area Manager P.O. BOX 31784 -

Subject: Fw: MIEP Documentation

LEARNING TOGETHER IN THE MPIKA INCLUSIVE EDUCATION PROJECT Child-to-Child Trust 2003 Contents Acknowledgements 3 1: How MIEP started and how it grew 4 2: Key strategies and techniques 14 3: A six-step approach approach to learning and action 22 4: Lessons from the project 30 2 Acknowledgements The text of this document was drafted by Patrick Kangwa (MIEP co-ordinator) and Grazyna Bonati (Child-to-Child Trust adviser), and edited by Prue Chalker (Child-to-Child Trust adviser) and Christine Scotchmer (Child-to-Child Trust executive secretary). William Gibbs (Child-to- Child Trust chairman) and Susie Miles (Enabling Education Network [EENET] co-ordinator, University of Manchester, UK) read the text and gave valuable comments. The text draws heavily on MIEP documentation, especially reports, lesson plans and case studies by the teachers and heads from the schools involved in the project. It also includes material from the project evaluation carried out by Gertrude Mwape from the University of Zambia and Freda Chisala. The illustrations are by David Gifford. MIEP was funded from 1999 to 2002 by Comic Relief. 3 1: How MIEP started and how it grew Introduction During the years 1999 to 2002, children with disabilities have studied in the regular classrooms of 17 local primary schools in the Mpika district of Northern Province, Zambia, as part of the Mpika Inclusive Education Project (MIEP). The term inclusive education is often taken to refer solely to the inclusion of children with disabilities in regular classrooms. However, in MIEP, the term inclusion has been extended over time to take on the broader meaning of including all marginalized children, whatever their circumstances, without discrimination, as outlined in the Salamanca Statement,1 and in accordance with the fundamental tenets of children’s rights. -

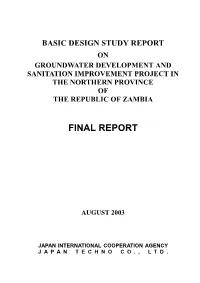

Final Report

BASIC DESIGN STUDY REPORT ON GROUNDWATER DEVELOPMENT AND SANITATION IMPROVEMENT PROJECT IN THE NORTHERN PROVINCE OF THE REPUBLIC OF ZAMBIA FINAL REPORT AUGUST 2003 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY JAPAN TECHNO CO., LTD. Lake Tanganyika GROUNDWATER DEVELOPMENT AND SANITATION Lake Lake Mweru TANZANIA IMPROVEMENT PROJECT IN THE NORTHERN PROVINCE Mweru Wantipa Mpulungu OF THE REPUBLIC OF ZAMBIA Mbala N ⑥ ⑤ Republic of ZAMBIA LOCATION MAP OF PROJECT AREA Kalungwishi ④ Nakonde Isoka Luwingu Kasama ③ ⑦ ChambeshiChinsali DEMOCRATIC Lake ② REPUBLIC Bangweulu OF CONGO Luapula : Project Area Mansa (7 Districts ) ⑥ ⑤ Lake ④ Kampolombp Northern ③ Province Bangweulu ⑦ Solwezi ① Mpika ② Swamp Luapula Province ① Copper North- Western -belt Province Province Province Luangwa Luwombwa Central Province Easterne Ndola KABOMPO Western Lusaka Province Province KAFUE MALAWI Southern Province LUNGWEBUNGU Chipata PONGWE Busanga Swamp Number of Lukanga Project Area Swamp Survey Sites Lunsemfwa Mongu ① Mpika Dist. 45 MOZAMBIQUE ② Chinsali Dist. 36 LUSAKA Zambezi National Capital ③ Isoka Dist. 43 Provincial Headquarters ④ Nakonde Dist. 36 District Headquarters ⑤ Mbala Dist. 53 International Boundary Provincial Boundary ZAMBEZI KARIBA ⑥ Mpulungu Dist. 43 ANGOLA District Boundary ⑦ Luwingu Dist. 44 LAKE ZIMBABWE km Total of Survey Sites 300 0 100 200 NAMIBIA KALOMO BOTSWANA Livingstone LIST OF FIGURES AND TABLES Figures Page Figure 2-1 Location Map of Project Sites ……………………………………… 2-7 Figure 2-2 Organization Chart of Ministry of Energy and Water Development -

The Role and Conditions of Service

THE ROLE AND CONDITIONS OF SERVICE OF AFRICAN MEDICAL AUXILIARIES IN CATHOLIC MISSION HEALTH INSTITUTIONS IN ZAMBIA: A CASE STUDY OF CHILONGA MISSION HOSPITAL IN MPIKA DISTRICT, 1905-1973 BY GODFREY KABAYA KUMWENDA A Dissertation Submitted to the University of Zambia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History. THE UNIVERSITY OF ZAMBIA LUSAKA © 2015 i ii DECLARATION This dissertation is the result of my own work and has not previously been submitted for a degree at this or any other university and does not incorporate any an unacknowledged published work or material from another dissertation. Signed ……………………………………….. Date …………………………………………. i COPYRIGHT All rights reserved. No part of this dissertation may be produced or stored in any form or by any means without prior permission in writing from the author or the University of Zambia. ii APPROVAL This dissertation of Godfrey Kabaya Kumwenda is approved as fulfilling the partial requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Arts in History by the University of Zambia. Signed: Date ............................................ ……………………………. ……………………………... ……………………………. ……………………………… …………………………… ……………………………. ……………………………. iii ABSTRACT Many studies on missionary medicine ignore the functions that African medical auxiliaries performed in colonial mission hospitals and clinics. These studies do not also examine the conditions of service under which auxiliaries lived and worked. This is because studies on missionary medicine in Africa focus on the activities and achievements of European doctors and nurses. Such studies push African medical employees to the lowest level of missionary hospital hierarchies and exhort Western doctors. Therefore, there is little knowledge about the role auxiliaries play in mission hospital and about their social and economic life. -

Hipc Northern Province Report 1.0 Executive Summary

HIPC NORTHERN PROVINCE REPORT 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The third tracking and monitoring visit to Northern Province started in June 2003 after the second visit to Lusaka Province of November 2002. A total of 80 projects were inspected and evaluated. This is more than 75% of the total number of projects funded from 2001, the beginning of HIPC disbursements for poverty reduction programmes. The Team flagged off the tracking and monitoring by first calling upon the Provincial Permanent Secretary’s Office and through that office requested for meetings with first the Provincial Heads of Government Departments to get an overview of the management of the HIPC funds and indeed the implementation of the projects and programmes. The Heads of Departments or their representatives shared their experiences with the Team and indeed made observations and recommendations on how best to enhance the management process of ensuring that the intended target population equitably benefited from the poverty reduction programmes financed by the HIPC funds. The Team also took opportunity of the meetings to once more emphasise on the need to promote transparency and accountability through the strict adherence to the HIPC Guidelines and indeed used the findings from the other provinces as cases for better management. At district level, the Team also called on the Offices of the District Administrators and had similar meetings with the District Heads of Government Departments like those held at the provincial level. Kaputa district was not visited as it was the Team’s view that the district was easier visited when inspecting and evaluating HIPC projects in Luapula Province. -

Main Document.Pdf

Declaration I hereby declare that the work presented in this study for a Masters’ Degree of Public Health is the product of my own work and that it has not been presented for any other degree. It has been prepared in accordance with the guidelines for Master of Public Health Dissertation of the University of Zambia. I further declare that, other peoples’ work has been duly acknowledged and referenced thereto, to which I owe them. Signed………………………………………………………. Date………………………………… Candidate Supervisors: We the undersigned have read this dissertation and have approved it for examination. Signed ……………………………………………………. Date……………………………….. Supervisor Signed ……………………………………………………. Date……………………………….. Supervisor i Approval of Admission of Dissertation This dissertation bySr.Rosemary Mwaba Kabonga is in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the Master of Public Health degree (MPH) by the University of Zambia, Lusaka. Examiners: ………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Names: ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………. Signature. …………………………………………………………………………………………………………. Date:………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. Examiners:.………………………………………………………………………………………………………. Names: ………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. Signature:……………………………………………………………………………………………………….. Date:…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. Head of Department Names: ………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. Signature:………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Date:……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ii Dedication This dissertation is affectionately dedicated