A Relational Theory of Fair Trade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bob Baffert, Five Others Enter Hall of Fame

FREE SUBSCR ER IPT IN IO A N R S T COMPLIMENTS OF T !2!4/'! O L T IA H C E E 4HE S SP ARATOGA Year 9 • No. 15 SARATOGA’S DAILY NEWSPAPER ON THOROUGHBRED RACING Friday, August 14, 2009 Head of the Class Bob Baffert, five others enter Hall of Fame Inside F Hall of Famer profiles Racing UK F Today’s entries and handicapping PPs Inside F Dynaski, Mother Russia win stakes DON’T BOTHER CHECKING THE PHOTO, THE WINNER IS ALWAYS THE SAME. YOU WIN. You win because that it generates maximum you love explosive excitement. revenue for all stakeholders— You win because AEG’s proposal including you. AEG’s proposal to upgrade Aqueduct into a puts money in your pocket world-class destination ensuress faster than any other bidder, tremendous benefits for you, thee ensuring the future of thorough- New York Racing Associationn bred racing right here at home. (NYRA), and New York Horsemen, Breeders, and racing fans. THOROUGHBRED RACING MUSEUM. AEG’s Aqueduct Gaming and Entertainment Facility will have AEG’s proposal includes a Thoroughbred Horse Racing a dazzling array Museum that will highlight and inform patrons of the of activities for VLT REVENUE wonderful history of gaming, dining, VLT OPERATION the sport here in % retail, and enter- 30 New York. tainment which LOTTERY % AEG The proposed Aqueduct complex will serve as a 10 will bring New world-class gaming and entertainment destination. DELIVERS. Yorkers and visitors from the Tri-State area and beyond back RACING % % AEG is well- SUPPORT 16 44 time and time again for more fun and excitement. -

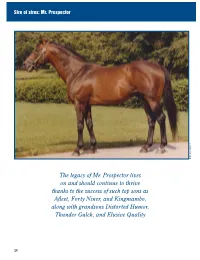

The Legacy of Mr. Prospector Lives on and Should Continue to Thrive

Sire of sires: Mr. Prospector Dell Hancock photo The legacy of Mr. Prospector lives on and should continue to thrive thanks to the success of such top sons as Afleet, Forty Niner, and Kingmambo, along with grandsons Distorted Humor, Thunder Gulch, and Elusive Quality 14 A tree of many branches Grandson of the great Native Dancer has numerous male-line descendants at stud BY JOHN P. SPARKMAN Northern Dancer.) The male lines of Alydar, THE CURRENT level of influence Exclusive Native, *Sea-Bird, of Thoroughbred racing’s first and Sharpen Up all have faded television hero, Native Dancer, over time, but the line of Mr. could hardly have been predicted Prospector has thrived under at his death in 1967. Forty-three modern conditions and spread years on, there are more male- worldwide. line descendants of Native Dancer in the THOROUGHBRED TIMES Commercial star Stallion Directory, mostly through Bred in Kentucky by Leslie his grandson Mr. Prospector, than Combs II, Mr. Prospector was of any of his contemporaries. the second foal of Gold Digger, An undefeated two-year-old by Nashua, a very good race- champion in 1952, Native Dancer mare who was a great-grand- raced into the nation’s con- daughter of the Combs family’s sciousness in his only losing ef- great foundation mare fort, the 1953 Kentucky Derby. Myrtlewood, by Blue Larkspur. Short of work off a rushed prepa- Champion sprinter and cham- ration, he fell just a head short of Leonard photo Tony pion handicap mare of 1936, catching the classy front-runner Conquistador Cielo, who along with Fusaichi Pegasus ranks among Myrtlewood produced cham- Dark Star after encountering Mr. -

Sunset Thomas (2002)

TesioPower Rancho San Antonio Sunset Thomas (2002) Pharos PHALARIS 1 NEARCO Scapa Flow 13 Nogara Havresac II 8 Nearctic (1954) Catnip 4-r HYPERION Gainsborough 2 Lady Angela SELENE 6 Sister Sarah Abbots Trace 4-j Northern Dancer (1961) Sarita 14-c Polynesian Unbreakable 4 NATIVE DANCER Black Polly 14-a Geisha DISCOVERY 23 Natalma (1957) Miyako 5-f MAHMOUD Blenheim II 1 ALMAHMOUD Mah Mahal 9-c Arbitrator Peace Chance 10-d Dixieland Band (1980) Mother Goose 2 ALIBHAI HYPERION 6 Traffic Judge Teresina 6 Traffic Court DISCOVERY 23 Delta Judge (1960) Traffic 3-n Noor NASRULLAH 9 Beautillion Queen Of Baghdad 16-h Delta Queen Bull Lea 9 Mississippi Mud (1973) Bleebok 12-c Determine ALIBHAI 6 Warfare Koubis 5-j War Whisk War Glory 11-b Sand Buggy (1963) Tidy Whisk 4-m Heliopolis HYPERION 6 Egyptian Drift 8 Evening Mist EIGHT THIRTY 11 Dixie Union (1997) Misty Isle 4-m Boldnesian BOLD RULER 8 Bold Reasoning Alanesian 4 Reason To Earn HAIL TO REASON 4-n Seattle Slew (1974) Sailing Home 1-k Poker Round Table 2 My Charmer Glamour 1-x Fair Charmer Jet Action 1 Capote (1984) Myrtle Charm 13 NASRULLAH NEARCO 4 Bald Eagle Mumtaz Begum 9 Siama Tiger 13 Too Bald (1964) China Face 4-m Dark Star Royal Gem II 1 Hidden Talent Isolde 3-n Dangerous Dame NASRULLAH 9 She's Tops (1989) Lady Kells 21 NATIVE DANCER Polynesian 14 Raise A Native Geisha 5-f Raise You Case Ace 1-k Mr Prospector (1970) Lady Glory 8-f Nashua NASRULLAH 9 Gold Digger Segula 3-m Sequence Count Fleet 6 She's A Talent (1983) Miss Dogwood 13 BOLD RULER NASRULLAH 9 Bold Hour Miss Disco 8 Seven -

The 2020 the 2020

Saturday, July 4, 2020 Year 1 • No. 5 The 2020 Unique Thoroughbred Racing Coverage Since 2001 Mr. Met Code Of Honor eyes Grade 1 Mile Tod Marks Tod 2 THE 2020 SPECIAL SATURDAY, JULY 4, 2020 Tod Marks Saturday Horse. Steeplechaser Lonely Weekend lives up to his name – perfect for a pandemic – before running at the Virginia Gold Cup last weekend. NAMES OF THE DAYBelmont Park here&there...in racing Mr Jaggers, fourth race. Pam and Marty Wygod’s homebred 3-year-old is named for a character in the Charles Dickens nov- Presented by Shadwell Farm el Great Expectations, as is his dam Miss Havisham. BY THE NUMBERS 1.1: Million dollars paid for most expensive horse at Fasig-Tipton Midlantic 2-year-olds in training sale – Hip 118, Pilot Episode, sixth race. Chiefswood Stable’s homebred filly 1:10: Post time for regular race days at the upcoming spec- Virginia-bred colt by Uncle Mo out of the Mineshaft mare Miss is out of Original Script. tator-free Saratoga Race Course meeting. Cards with a steeple- Ocean City purchased by Michael Lund Petersen and sold by chase race will start at 12:50 p.m. Pike Racing. Cross Border, 10th race. The 6-year-old is a son of English Channel and Empresse Josephine. 2: Hours of coverage of Saturday’s Epsom Derby and Epsom 23,572,500: Dollars paid for the 303 horses reported sold Oaks on FS1 starting at 10 a.m. EDT. at the Fasig-Tipton Midlantic 2-year-olds in training sale Mon- day and Tuesday in Timonium, Md. -

Moon Deck (QH) (1950)

TesioPower jadehorse Moon Deck (QH) (1950) Domino 23 Commando Emma C 12 PETER PAN HERMIT 5 Cinderella Mazurka 2 Pennant (1911) Hampton 10 Royal Hampton PRINCESS 11 Royal Rose Beaudesert 8 Belle Rose Monte Rosa 8 Equipoise (1928) Bramble 9 Ben Brush Roseville A1 BROOMSTICK Galliard 13 Elf SYLVABELLE 16 Swinging (1922) St Gatien 16 Meddler Busybody 1 Balancoire II Ayrshire 8 Ballantrae Abeyance 5 Equestrian (1936) Spendthrift A3 Hastings Cinderella 21 Fair Play TADCASTER Fairy Gold Dame Masham 9 MAN O' WAR (1917) Sainfoin 2 Rock Sand Roquebrune 4 Mahubah Merry Hampton 22 Merry Token Mizpah 4 Frilette (1924) Bramble 9 Ben Brush Roseville A1 BROOMSTICK Galliard 13 Elf SYLVABELLE 16 Frillery (1913) HANOVER 15 HAMBURG Lady Reel 23 Petticoat SIR DIXON 4 Elusive Vega A1 Top Deck (1945) Musket 3 Carbine The Mersey 2 SPEARMINT Minting 1 Maid Of The Mint Warble 1 Chicle (1913) HANOVER 15 HAMBURG Lady Reel 23 Lady Hamburg II ST SIMON 11 Lady Frivoles Gay Duchess 31 Chicaro (1923) Domino 23 Commando Emma C 12 PETER PAN HERMIT 5 Cinderella Mazurka 2 Wendy (1917) Ben Brush A1 BROOMSTICK Elf 16 Remembrance Exile 19 Forget Forever 5 River Boat () Flying Fox 7 Ajax Amie 2 Teddy Bay Ronald 3 Rondeau Doremi 2 Sir Gallahad III (1920) Carbine 2 SPEARMINT Maid Of The Mint 1 Plucky Liege ST SIMON 11 Concertina Comic Song 16 Last Boat (1932) Hastings 21 Fair Play Fairy Gold 9 MAN O' WAR Rock Sand 4 Mahubah Merry Token 4 Taps (1923) Ben Brush A1 BROOMSTICK Elf 16 Shady Disguise II 10 Sylvan SYLVABELLE 16 Isonomy 19 Moon Deck (QH) (1950) Isinglass Dead Lock 3 John -

War Relic A++ Based on the Cross of Fair Play and His Sons/Friar Rock Variant = 13.41 Breeder: (USA)

09/28/13 12:48:10 EDT War Relic A++ Based on the cross of Fair Play and his sons/Friar Rock Variant = 13.41 Breeder: (USA) *Australian, 58 ch Spendthrift, 76 ch Aerolite, 61 ch Hastings, 93 br =Tomahawk (GB), 63 br *Cinderella, 85 b =Manna, 74 b Fair Play, 05 =Doncaster (GB), 70 ch =Bend Or (GB), 77 ch =Rouge Rose (GB), 65 ch *Fairy Gold, 96 ch =Galliard (GB), 80 dk b/ =Dame Masham (GB), 89 br =Pauline (GB), 83 b Man o' War, 17 ch =Springfield (GB), 73 b =Sainfoin (GB), 87 ch =Sanda (GB), 78 ch *Rock Sand, 00 br =St. Simon (GB), 81 b =Roquebrune (GB), 93 br =St Marguerite (GB), 79 Mahubah, 10 ch =Hampton (GB), 72 b =Merry Hampton (GB), 84 b =Doll Tearsheet (GB), 77 *Merry Token, 91 b b War Relic =Macgregor (GB), 67 b Chestnut Horse =Mizpah, 80 b Foaled Jan 01, 1938 =Underhand Mare (GB), in United States 63 b =Springfield (GB), 73 b =Sainfoin (GB), 87 ch =Sanda (GB), 78 ch *Rock Sand, 00 br =St. Simon (GB), 81 b =Roquebrune (GB), 93 br =St Marguerite (GB), 79 Friar Rock, 13 ch =Doncaster (GB), 70 ch =Bend Or (GB), 77 ch =Rouge Rose (GB), 65 ch *Fairy Gold, 96 ch =Galliard (GB), 80 dk b/ =Dame Masham (GB), 89 Friar's Carse, 23 ch br =Pauline (GB), 83 b Domino, 91 Commando, 98 b Emma C., 92 b Superman, 04 ch =Bend Or (GB), 77 ch *Anomaly, 96 ch =Blue Rose (GB), 92 b Problem, 14 =Friar's Balsam (GB), 85 *Voter, 94 ch ch Query, 06 ch *Mavourneen, 88 ch Himyar, 75 b Quesal, 86 b Queen Ban, 80 ch Pedigree Statistics Dosage Information Coefficient of Relatedness: 13.87% Pedigree Completeness: 100.00% Dosage Profile: 0 0 4 24 4 Inbreeding Coefficient: -

2020 International List of Protected Names

INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (only available on IFHA Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 03/06/21 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne-Billancourt, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org The list of Protected Names includes the names of : Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally renowned, either as main stallions and broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or jump) From 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine following international races : South America : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil Asia : Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup Europe : Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes North America : Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf Since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous following international races : South America : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil Asia : Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup Europe : Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion North America : Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf The main stallions and broodmares, registered on request of the International Stud Book Committee (ISBC). Updates made on the IFHA website The horses whose name has been protected on request of a Horseracing Authority. Updates made on the IFHA website * 2 03/06/2021 In 2020, the list of Protected -

WILD COURT 2006 Bay - Height 16.0 - Dosage Profile: 4-1-3-0-0; DI: 4.33; CD: +1.13

WILD COURT 2006 Bay - Height 16.0 - Dosage Profile: 4-1-3-0-0; DI: 4.33; CD: +1.13 Native Dancer RACE AND (STAKES) RECORD Raise a Native Raise You Age Starts 1st 2nd 3rd Earnings Native Royalty *Nasrullah 2 unraced Queen Nasra Bayborough 3 unraced Ruthie’s Native Bull Lea 4 5000 $3,600 Citation *Hydroplane II Right About *Blenheim II IN THE STUD Whirl Right Dustwhirl Arlene’s Valentine (1985) WILD COURT entered stud in 2012. His first foals are 4- Polynesian Native Dancer year-olds of 2016. Geisha Grand Revival *Princequillo Venice MALE LINE Delta Odessa J. C. Johnstown WILD COURT is by ARLENE’S VALENTINE, stakes win- Gee Whiz Blessed Again ner of 8 races, 2 to 4, $320,486, Red Bank H.-G3, Fort Daughter Whiz War Relic War Amber Marcy H.-G3, Japan Racing Association H.-L, Palisades Second Spring Wild Court H.-L, Restoration S., New Jersey Breeders’ S.-R, 2nd Boldnesian Bold Reasoning Reason to Earn Choice H.-G3, Camden County S., Mercer County S., Seattle Slew Poker 3rd Bougainvillea H.-G2, Camden H.-L. Sire of-- My Charmer Fair Charmer Browneyedvalentine. Placed at 3. Turkey Shoot *Khaled Swaps Iron Reward Lovely Morning WILD COURT’s granddsire is RUTHIE’S NATIVE, stakes *Princequillo Misty Morn Grey Flight winner of 7 races to 3, $209,533, Florida Derby-G1, Downy Miss (1996) *Nasrullah Fountain of Youth S.-G3, Tropical Park Derby, 2nd Nash- Bald Eagle Siama ua S., 3rd Minuteman H.-G3. Sire of 13 stakes winners-- Road At Sea *Turn-to Hard-a-Lee BROUGHT TO MIND. -

2008 International List of Protected Names

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities _________________________________________________________________________________ _ 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Avril / April 2008 Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : ) des gagnants des 33 courses suivantes depuis leur ) the winners of the 33 following races since their création jusqu’en 1995 first running to 1995 inclus : included : Preis der Diana, Deutsches Derby, Preis von Europa (Allemagne/Deutschland) Kentucky Derby, Preakness Stakes, Belmont Stakes, Jockey Club Gold Cup, Breeders’ Cup Turf, Breeders’ Cup Classic (Etats Unis d’Amérique/United States of America) Poule d’Essai des Poulains, Poule d’Essai des Pouliches, Prix du Jockey Club, Prix de Diane, Grand Prix de Paris, Prix Vermeille, Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe (France) 1000 Guineas, 2000 Guineas, Oaks, Derby, Ascot Gold Cup, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, St Leger, Grand National (Grande Bretagne/Great Britain) Irish 1000 Guineas, 2000 Guineas, Derby, Oaks, Saint Leger (Irlande/Ireland) Premio Regina Elena, Premio Parioli, Derby Italiano, Oaks (Italie/Italia) -

Man O' War by Kathleen Jones

Man o' War by Kathleen Jones There is very little one can say about Man o' War which has not already been said, but it would be unconscionable to remain silent in regards to the most beloved figure in American racing history. Man o' War was the second foal of his dam, the first having been a full sister named Masda. Masda was a stakes winner but is probably more important as the third dam of Triple Crown winner, Assault. Man o' War's dam, Mahubah was sometimes referred to as "Fair Play's wife" as she produced foals only to that stallion. Man o' War was born a few minutes before midnight, on March 29, and quickly grew into a big horse of great power. His chestnut coat and imposing presence earned him the nickname "Big Red." When his trainer, Louis Reustel, first laid eyes on him as a yearling, he described him as "very tall, gangly and thin. So leggy as to give the same impression one gets when seeing a week-old foal." Perhaps not the powerhouse as a yearling that he would be later in life, he sold at Saratoga's yearling sale in August 1918 for $5000. Man o' War debuted at Belmont Park on June 6th, 1919, in a purse race against six other contenders. He won easily by 6 lengths. Three days later, he stepped up to stakes company and dusted five others in the Keene Memorial Stakes. Rested for eleven days, he reappeared to win the Youthful Stakes at Jamaica Park. Then, two days after that, was showed up at Aqueduct where he was entered in the Hudson Stakes. -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

Download the Free Meet the Triple Crown Winners

MEET THE TRIPLE CROWN WINNERS MEET THE TRIPLE CROWN WINNERS JUSTIFY 2018 3 AMERICAN PHAROAH 2015 5 AFFIRMED 1978 7 SEATTLE SLEW 1977 9 SECRETARIAT 1973 11 CITATION 1948 13 ASSAULT 1946 15 COUNT FLEET 1943 17 WHIRLAWAY 1941 19 WAR ADMIRAL 1937 21 OMAHA 1935 23 GALLANT FOX 1930 25 SIR BARTON 1919 27 Key Facts and Pedigree Fun Facts written by Kellie Reilly MEET THE TRIPLE CROWN WINNERS 2 TRIPLE CROWN WINNERS Justify American Pharoah AFFIRMEd Seattle Slew 2018 2015 1978 1977 Secretariat Citation Assault Count Fleet 1973 1948 1946 1943 Whirlaway War Admiral Omaha Gallant Fox 1941 1937 1935 1930 Sir Barton 1919 MEET THE TRIPLE CROWN WINNERS 3 2018CHAMPION JUSTIFY The latest Triple Crown winner defied precedent twice over: Justify did not race at two and finished his meteoric career unbeaten. KEY FACTS Bred by the father-daughter team of John and Tanya Gunther at Trained like American Pharoah Glennwood Farm, Justify commanded $500,000 as a Keeneland by Bob Baffert, the $500,000 September yearling. He hailed from the penultimate crop of international Keeneland September yearling sire Scat Daddy. set an entirely different historical marker by becoming the first Justify’s ownership consortium was led by WinStar Farm and China Horse unraced 2-year-old to win the Club, with SF Racing also involved. Head of Plains Partners and Starlight Triple Crown. Racing came aboard after his debut. That premiere didn’t come until February 18, 2018 – by historical Justify pressed a fast pace in the standards, too late to sweep the Triple Crown. No unraced juvenile had slop at Churchill Downs (becoming even won the Kentucky Derby since Apollo in 1882, long before the Triple the first Derby winner to start his Crown era.