Return for America's Red Wolves

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

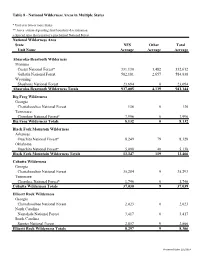

Table 8 — National Wilderness Areas in Multiple States

Table 8 - National Wilderness Areas in Multiple States * Unit is in two or more States ** Acres estimated pending final boundary determination + Special Area that is part of a proclaimed National Forest National Wilderness Area State NFS Other Total Unit Name Acreage Acreage Acreage Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness Montana Custer National Forest* 331,130 1,482 332,612 Gallatin National Forest 582,181 2,657 584,838 Wyoming Shoshone National Forest 23,694 0 23,694 Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness Totals 937,005 4,139 941,144 Big Frog Wilderness Georgia Chattahoochee National Forest 136 0 136 Tennessee Cherokee National Forest* 7,996 0 7,996 Big Frog Wilderness Totals 8,132 0 8,132 Black Fork Mountain Wilderness Arkansas Ouachita National Forest* 8,249 79 8,328 Oklahoma Ouachita National Forest* 5,098 40 5,138 Black Fork Mountain Wilderness Totals 13,347 119 13,466 Cohutta Wilderness Georgia Chattahoochee National Forest 35,284 9 35,293 Tennessee Cherokee National Forest* 1,746 0 1,746 Cohutta Wilderness Totals 37,030 9 37,039 Ellicott Rock Wilderness Georgia Chattahoochee National Forest 2,023 0 2,023 North Carolina Nantahala National Forest 3,417 0 3,417 South Carolina Sumter National Forest 2,857 9 2,866 Ellicott Rock Wilderness Totals 8,297 9 8,306 Processed Date: 2/5/2014 Table 8 - National Wilderness Areas in Multiple States * Unit is in two or more States ** Acres estimated pending final boundary determination + Special Area that is part of a proclaimed National Forest National Wilderness Area State NFS Other Total Unit Name Acreage Acreage -

After Long-Term Decline, Are Aspen Recovering in Northern Yellowstone? ⇑ Luke E

Forest Ecology and Management 329 (2014) 108–117 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Forest Ecology and Management journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foreco After long-term decline, are aspen recovering in northern Yellowstone? ⇑ Luke E. Painter a, , Robert L. Beschta a, Eric J. Larsen b, William J. Ripple a a Department of Forest Ecosystems and Society, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331, USA b Department of Geography and Geology, University of Wisconsin – Stevens Point, Stevens Point, WI 54481-3897, USA article info abstract Article history: In northern Yellowstone National Park, quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides) stands were dying out in the Received 18 December 2013 late 20th century following decades of intensive browsing by Rocky Mountain elk (Cervus elaphus). In Received in revised form 28 May 2014 1995–1996 gray wolves (Canis lupus) were reintroduced, joining bears (Ursus spp.) and cougars (Puma Accepted 30 May 2014 concolor) to complete the guild of large carnivores that prey on elk. This was followed by a marked decline in elk density and change in elk distribution during the years 1997–2012, due in part to increased pre- dation. We hypothesized that these changes would result in less browsing and an increase in height of Keywords: young aspen. In 2012, we sampled 87 randomly selected stands in northern Yellowstone, and compared Wolves our data to baseline measurements from 1997 and 1998. Browsing rates (the percentage of leaders Elk Browsing effects browsed annually) in 1997–1998 were consistently high, averaging 88%, and only 1% of young aspen Trophic cascade in sample plots were taller than 100 cm; none were taller than 200 cm. -

Wilderness Visitors and Recreation Impacts: Baseline Data Available for Twentieth Century Conditions

United States Department of Agriculture Wilderness Visitors and Forest Service Recreation Impacts: Baseline Rocky Mountain Research Station Data Available for Twentieth General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-117 Century Conditions September 2003 David N. Cole Vita Wright Abstract __________________________________________ Cole, David N.; Wright, Vita. 2003. Wilderness visitors and recreation impacts: baseline data available for twentieth century conditions. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-117. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 52 p. This report provides an assessment and compilation of recreation-related monitoring data sources across the National Wilderness Preservation System (NWPS). Telephone interviews with managers of all units of the NWPS and a literature search were conducted to locate studies that provide campsite impact data, trail impact data, and information about visitor characteristics. Of the 628 wildernesses that comprised the NWPS in January 2000, 51 percent had baseline campsite data, 9 percent had trail condition data and 24 percent had data on visitor characteristics. Wildernesses managed by the Forest Service and National Park Service were much more likely to have data than wildernesses managed by the Bureau of Land Management and Fish and Wildlife Service. Both unpublished data collected by the management agencies and data published in reports are included. Extensive appendices provide detailed information about available data for every study that we located. These have been organized by wilderness so that it is easy to locate all the information available for each wilderness in the NWPS. Keywords: campsite condition, monitoring, National Wilderness Preservation System, trail condition, visitor characteristics The Authors _______________________________________ David N. -

Report Highlights

Consensus Study Report October 2020 HIGHLIGHTS A Research Strategy to Examine the Taxonomy of the RED WOLF Dramatic reductions in the population of modern WHY DO MORE RESEARCH ON red wolf, Canis rufus in the eastern United States led to THE RED WOLF? their re-introduction by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service There are three possible explanations for the significant (USFWS) into North Carolina in the early 1980s. Since amount of coyote ancestry in modern red wolves. First, then, USFWS has managed a population of red wolves that the extant red wolves may be hybrids between coyotes was established from re-introduced individuals. However, and either gray wolves or what were once red wolves. subsequent genetic studies of the managed population Hybridization may have occurred long ago or in more indicated that these wolves displayed evidence of significant recent years. Evidence suggests that some hybridization coyote ancestry. This discovery raised the issue of whether certainly occurred in the 20th century as red wolf the extant managed1 population in North Carolina was a populations dwindled in size while coyotes expanded valid species that was eligible for conservation and recovery. their range eastward. Second, the extant red wolves may In March 2019, at the request of USFWS, the National have diverged from coyotes recently enough that they Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine issued continue to share alleles, even though each species has its a report that provided evidence that retained the existing own forward evolutionary trajectory— a situation referred taxonomic designation of the red wolf and reinforced the to as incomplete lineage sorting. -

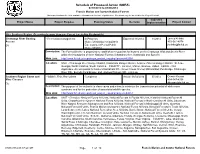

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA)

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 07/01/2014 to 09/30/2014 Francis Marion and Sumter National Forests This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact R8 - Southern Region, Occurring in more than one Forest (excluding Regionwide) Chattooga River Boating - Recreation management In Progress: Expected:11/2014 11/2014 James Knibbs Access Notice of Initiation 07/24/2013 803-561-4078 EA Est. Comment Period Public [email protected] Notice 07/2014 Description: The Forest Service is proposing to establish access points for boaters on the Chattooga Wild and Scenic River within the boundaries of three National Forests (Chattahoochee, Nantahala and Sumter). Web Link: http://www.fs.fed.us/nepa/nepa_project_exp.php?project=42568 Location: UNIT - Chattooga River Ranger District, Nantahala Ranger District, Andrew Pickens Ranger District. STATE - Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina. COUNTY - Jackson, Macon, Oconee, Rabun. LEGAL - Not Applicable. Access points for boaters:Nantahala RD - Green Creek; Norton Mill and Bull Pen Bridge; Chattooga River RD - Burrells Ford Bridge; and, Andrew Pickens RD - Lick Log. Southern Region Caves and - Wildlife, Fish, Rare plants Completed Actual: 06/02/2014 07/2014 Dennis Krusac Mine Closures 404-347-4338 CE [email protected] Description: The purpose of the action is to close caves and mines to minimize the transmission potential of white nose -

Wolf Interactions with Non-Prey

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln USGS Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center US Geological Survey 2003 Wolf Interactions with Non-prey Warren B. Ballard Texas Tech University Ludwig N. Carbyn Canadian Wildlife Service Douglas W. Smith US Park Service Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsnpwrc Part of the Animal Sciences Commons, Behavior and Ethology Commons, Biodiversity Commons, Environmental Policy Commons, Recreation, Parks and Tourism Administration Commons, and the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Ballard, Warren B.; Carbyn, Ludwig N.; and Smith, Douglas W., "Wolf Interactions with Non-prey" (2003). USGS Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center. 325. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsnpwrc/325 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the US Geological Survey at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in USGS Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 10 Wolf Interactions with Non-prey Warren B. Ballard, Ludwig N. Carbyn, and Douglas W. Smith WOLVES SHARE THEIR ENVIRONMENT with many an wolves and non-prey species. The inherent genetic, be imals besides those that they prey on, and the nature of havioral, and morphological flexibility of wolves has the interactions between wolves and these other crea allowed them to adapt to a wide range of habitats and tures varies considerably. Some of these sympatric ani environmental conditions in Europe, Asia, and North mals are fellow canids such as foxes, coyotes, and jackals. America. Therefore, the role of wolves varies consider Others are large carnivores such as bears and cougars. -

Land Areas of the National Forest System, As of September 30, 2019

United States Department of Agriculture Land Areas of the National Forest System As of September 30, 2019 Forest Service WO Lands FS-383 November 2019 Metric Equivalents When you know: Multiply by: To fnd: Inches (in) 2.54 Centimeters Feet (ft) 0.305 Meters Miles (mi) 1.609 Kilometers Acres (ac) 0.405 Hectares Square feet (ft2) 0.0929 Square meters Yards (yd) 0.914 Meters Square miles (mi2) 2.59 Square kilometers Pounds (lb) 0.454 Kilograms United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Land Areas of the WO, Lands National Forest FS-383 System November 2019 As of September 30, 2019 Published by: USDA Forest Service 1400 Independence Ave., SW Washington, DC 20250-0003 Website: https://www.fs.fed.us/land/staff/lar-index.shtml Cover Photo: Mt. Hood, Mt. Hood National Forest, Oregon Courtesy of: Susan Ruzicka USDA Forest Service WO Lands and Realty Management Statistics are current as of: 10/17/2019 The National Forest System (NFS) is comprised of: 154 National Forests 58 Purchase Units 20 National Grasslands 7 Land Utilization Projects 17 Research and Experimental Areas 28 Other Areas NFS lands are found in 43 States as well as Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. TOTAL NFS ACRES = 192,994,068 NFS lands are organized into: 9 Forest Service Regions 112 Administrative Forest or Forest-level units 503 Ranger District or District-level units The Forest Service administers 149 Wild and Scenic Rivers in 23 States and 456 National Wilderness Areas in 39 States. The Forest Service also administers several other types of nationally designated -

United States Department of the Interior

United States Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service RG Stephens, Jr. Federal Building 355 E. Hancock Ave, Room 320, Box 7 Athens, GA 30601 West Georgia Sub Office Coastal Georgia Sub Office Post Office Box 52560 4980 Wildlife Drive, NE Fort Benning, Georgia 31995-2560 Townsend, Georgia 31331 May 28, 2020 Colonel Daniel Hibner U.S. Anny Corps of Engineers Savannah District - Regulatory Division 100 West Oglethorpe Avenue Savannah, Georgia 31401-3640 Attention: Ms. Holly Ross Re: USFWS File Number 2020-1618 Dear Colonel Hibner: The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) has reviewed the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) Joint Public Notice (JPN) SAS-2018-00554 and associated information concerning the proposed Twin Pines demonstration mining project (project) in Charlton County, Georgia. The project was proposed after a similar larger mining project application was withdrawn. We again appreciate the efforts expended by USACE to include the extensive supporting information in the JPN to aid in the review. As with the previous mining application, we have concerns that the proposed project may pose risks to the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge (OKENWR) and the natural environment due to the location, associated activities, and cumulative effects of similar projects in the area. We opine that the impacts are not sufficiently known and whatever is done may be permanent. We provide the following as information on issues to be considered in your decision on the level of environmental review that is appropriate for this proposed project. Our comments are submitted in accordance with provisions of the Endangered Species Act (ESA) of 1973, as amended; (16 U.S.C. -

Introduction

00i-xvi_Mohl-East-00-FM 2/18/06 8:25 AM Page xv INTRODUCTION During the rapid development of the United States after the American Rev- olution, and during most of the 1900s, many forests in the United States were logged, with the logging often followed by devastating fires; ranchers converted the prairies and the plains into vast pastures for livestock; sheep were allowed to venture onto heretofore undisturbed alpine areas; and great amounts of land were turned over in an attempt to find gold, silver, and other minerals. In 1875, the American Forestry Association was born. This organization was asked by Secretary of the Interior Carl Schurz to try to change the con- cept that most people had about the wasting of our natural resources. One year later, the Division of Forestry was created within the Department of Agriculture. However, land fraud continued, with homesteaders asked by large lumber companies to buy land and then transfer the title of the land to the companies. In 1891, the American Forestry Association lobbied Con- gress to pass legislation that would allow forest reserves to be set aside and administered by the Department of the Interior, thus stopping wanton de- struction of forest lands. President Benjamin Harrison established forest re- serves totaling 13 million acres, the first being the Yellowstone Timberland Reserve, which later became the Shoshone and Teton national forests. Gifford Pinchot was the founder of scientific forestry in the United States, and President Theodore Roosevelt named him chief of the Forest Ser- vice in 1898 because of his wide-ranging policy on the conservation of nat- ural resources. -

Red Wolves: Creating Economic Opportunity Through Ecotourism in Rural North Carolina

Red Wolves: Creating Economic Opportunity Through Ecotourism in Rural North Carolina Report By Dr. Gail Y. B. Lash & Pamela Black Ursa International For Defenders of Wildlife Washington, DC February 2005 Red Wolves: Creating Economic Opportunity Through Ecotourism in Rural North Carolina Report By Dr. Gail Y. B. Lash & Pamela Black Ursa International Published By Defenders of Wildlife Washington, DC February 2005 Defenders of Wildlife 1130 Seventeenth Street NW Washington, DC 20036-4604 USA phone: 1-202-682-9400 web: http://www.defenders.org Ursa International 366 Oakland Ave., SE Atlanta, GA 30312-2233 USA phone: 1-404-222-9595 web: http://www.ursainternational.org Red Wolf Ecotourism Report, p. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Foreword .............................................................................................................................4 Executive Summary.............................................................................................................5 List of Tables .......................................................................................................................7 List of Figures......................................................................................................................8 List of Abbreviations ...........................................................................................................9 Introduction........................................................................................................................10 Purpose of Study....................................................................................................10 -

Red Wolf Brochure

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Endangered Red Wolves The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is reintroducing red wolves to prevent extinction of the species and to restore the ecosystems in which red wolves once occurred, as mandated by the Endangered Species Act of 1973. According to the Act, endangered and threatened species are of aesthetic, ecological, educational, historical, recreational, and scientific value to the nation and its people. On the Edge of Extinction The red wolf historically roamed as a top predator throughout the southeastern U.S. but today is one of the most endangered animals in the world. Aggressive predator control programs and clearing of forested habitat combined to cause impacts that brought the red wolf to the brink of extinction. By 1970, the entire population of red wolves was believed to be fewer than 100 animals confined to a small area of coastal Texas and Louisiana. In 1980, the red wolf was officially declared extinct in the wild, while only a small number of red wolves remained in captivity. During the 1970’s, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service established criteria which helped distinguish the red wolf species from other canids. From 1974 to 1980, the Service applied these criteria to find that only 17 red wolves were still living. Based on additional Greg Koch breeding studies, only 14 of these wolves were selected as founders to begin the red wolf captive breeding population. The captive breeding program is coordinated for the Service by the Point Defiance Zoo & Aquarium in Tacoma, Washington, with goals of conserving red wolf genetic diversity and providing red wolves for restoration to the wild. -

Our 25Th Year of Blazing a Trail for Longleaf Restoration

19005112_Longleaf-Leader-WINTER-2020_rev.qxp_Layout 1 1/9/20 10:44 AM Page 2 Our 25th Year of Blazing a Trail for Longleaf Restoration Volume Xii - issue 4 WiNTeR 2020 19005112_Longleaf-Leader-WINTER-2020_rev.qxp_Layout 1 1/9/20 10:44 AM Page 3 19005112_Longleaf-Leader-WINTER-2020_rev.qxp_Layout 1 1/9/20 10:44 AM Page 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS 14 56 23 44 10 President’s Message....................................................2 LANDOWNER CORNER .......................................23 Calendar ....................................................................4 TECHNOLOGY CORNER .....................................26 Letters from the Inbox ...............................................5 REGIONAL UPDATES .........................................29 Understory Plant Spotlight........................................7 Wildlife Spotlight .....................................................8 ARTS & LITERATURE ........................................40 2019 – A Banner Year for Longleaf ..........................10 Longleaf Destinations ..............................................44 The Alliance Teaches its 100th Longleaf Academy: PEOPLE .................................................................47 A Look Back............................................................14 SUPPORT THE ALLIANCE ................................50 RESEARCH NOTES .............................................18 Heartpine ................................................................56 PUBLISHER The Longleaf Alliance, E D I T O R Carol Denhof, ASSISTANT EDITOR