Undergraduate Dissertation Trabajo Fin De Grado

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blockbusters: Films and the Books About Them Display Maggie Mason Smith Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints Presentations University Libraries 5-2017 Blockbusters: Films and the Books About Them Display Maggie Mason Smith Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/lib_pres Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Mason Smith, Maggie, "Blockbusters: Films and the Books About Them Display" (2017). Presentations. 105. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/lib_pres/105 This Display is brought to you for free and open access by the University Libraries at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Presentations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Blockbusters: Films and the Books About Them Display May 2017 Blockbusters: Films and the Books About Them Display Photograph taken by Micki Reid, Cooper Library Public Information Coordinator Display Description The Summer Blockbuster Season has started! Along with some great films, our new display features books about the making of blockbusters and their cultural impact as well as books on famous blockbuster directors Spielberg, Lucas, and Cameron. Come by Cooper throughout the month of May to check out the Star Wars series and Star Wars Propaganda; Jaws and Just When you thought it was Safe: A Jaws Companion; The Dark Knight trilogy and Hunting the Dark Knight; plus much more! *Blockbusters on display were chosen based on AMC’s list of Top 100 Blockbusters and Box Office Mojo’s list of All Time Domestic Grosses. - Posted on Clemson University Libraries’ Blog, May 2nd 2017 Films on Display • The Amazing Spider-Man. Dir. Marc Webb. Perf. Andrew Garfield, Emma Stone, Rhys Ifans. -

Theaters 3 & 4 the Grand Lodge on Peak 7

The Grand Lodge on Peak 7 Theaters 3 & 4 NOTE: 3D option is only available in theater 3 Note: Theater reservations are for 2 hours 45 minutes. Movie durations highlighted in Orange are 2 hours 20 minutes or more. Note: Movies with durations highlighted in red are only viewable during the 9PM start time, due to their excess length Title: Genre: Rating: Lead Actor: Director: Year: Type: Duration: (Mins.) The Avengers: Age of Ultron 3D Action PG-13 Robert Downey Jr. Joss Whedon 2015 3D 141 Born to be Wild 3D Family G Morgan Freeman David Lickley 2011 3D 40 Captain America : The Winter Soldier 3D Action PG-13 Chris Evans Anthony Russo/ Jay Russo 2014 3D 136 The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader 3D Adventure PG Georgie Henley Michael Apted 2010 3D 113 Cirque Du Soleil: Worlds Away 3D Fantasy PG Erica Linz Andrew Adamson 2012 3D 91 Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs 2 3D Animation PG Ana Faris Cody Cameron 2013 3D 95 Despicable Me 3D Animation PG Steve Carell Pierre Coffin 2010 3D 95 Despicable Me 2 3D Animation PG Steve Carell Pierre Coffin 2013 3D 98 Finding Nemo 3D Animation G Ellen DeGeneres Andrew Stanton 2003 3D 100 Gravity 3D Drama PG-13 Sandra Bullock Alfonso Cuaron 2013 3D 91 Hercules 3D Action PG-13 Dwayne Johnson Brett Ratner 2014 3D 97 Hotel Transylvania Animation PG Adam Sandler Genndy Tartakovsky 2012 3D 91 Ice Age: Continetal Drift 3D Animation PG Ray Romano Steve Martino 2012 3D 88 I, Frankenstein 3D Action PG-13 Aaron Eckhart Stuart Beattie 2014 3D 92 Imax Under the Sea 3D Documentary G Jim Carrey Howard Hall -

RESISTANCE MADE in HOLLYWOOD: American Movies on Nazi Germany, 1939-1945

1 RESISTANCE MADE IN HOLLYWOOD: American Movies on Nazi Germany, 1939-1945 Mercer Brady Senior Honors Thesis in History University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Department of History Advisor: Prof. Karen Hagemann Co-Reader: Prof. Fitz Brundage Date: March 16, 2020 2 Acknowledgements I want to thank Dr. Karen Hagemann. I had not worked with Dr. Hagemann before this process; she took a chance on me by becoming my advisor. I thought that I would be unable to pursue an honors thesis. By being my advisor, she made this experience possible. Her interest and dedication to my work exceeded my expectations. My thesis greatly benefited from her input. Thank you, Dr. Hagemann, for your generosity with your time and genuine interest in this thesis and its success. Thank you to Dr. Fitz Brundage for his helpful comments and willingness to be my second reader. I would also like to thank Dr. Michelle King for her valuable suggestions and support throughout this process. I am very grateful for Dr. Hagemann and Dr. King. Thank you both for keeping me motivated and believing in my work. Thank you to my roommates, Julia Wunder, Waverly Leonard, and Jamie Antinori, for being so supportive. They understood when I could not be social and continued to be there for me. They saw more of the actual writing of this thesis than anyone else. Thank you for being great listeners and wonderful friends. Thank you also to my parents, Joe and Krista Brady, for their unwavering encouragement and trust in my judgment. I would also like to thank my sister, Mahlon Brady, for being willing to hear about subjects that are out of her sphere of interest. -

Jaap Buitendijk-CV.Docx

For portfolio & availability requests: Barbara Lakin Represents Tel. 702/379-9449 Fantastic Beasts: Part 1,2,3, Ready Player One, The Big Short, Bridge Of Spies, 12 Years a Slave, World War Z, Hugo, Harry Potter and The Deathly Hallows: Part 1 & 2, Children of Men, Gladiator Member of The Association Of Motion Picture Stills Photographers Winner Fuji Professional Award Publicists Guild of America Excellence in Unit Still Photography Nominee 2017 Publicists Guild of America Excellence in Unit Still Photography Nominee 2016 Member of IATSE Local 600 2020 Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them 3 director: David Yates cast: Mads Mikkelsen, Jude Law, Eddie Redmayne, Katherine Waterston, Ezra Miller client: Warner Bros. 2019 The Mauritanian (specials) director: Kevin Macdonald cast: Benedict Cumberbatch, Jodie Foster, Shailene Woodley, Zachary Levi client: SunnyMarch 2019 Louis Wain director: Will Sharpe cast: Benedict Cumberbatch, Claire Foy client: Amazon Studios, StudioCanal 2019 Downhill director: Nat Fixon, Jim Rash cast: Will Ferrell, Julia Louis-Dreyfus, Zach Woods client: Fox Searchlight Pictures 2018 Maleficent: Mistress of Evil director: Joachim Ronning cast: Angelina Jolie, Michelle Pfeiffer, Elle Fanning, Sam Reilly client: Walt Disney Pictures 2018 Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald director: David Yates cast: Eddie Redmayne, Katherine Waterston, Ezra Miller, Jude Law, Johnny Depp client: Warner Bros. 1 2018 Ready Player One director: Steven Spielberg cast: Tye Sheridan, Olivia Cooke, Mark Rylance, Simon Pegg client: Warner Bros. 2017 T2: Trainspotting director: Danny Boyle cast: Ewan McGregor, Robert Carlyle, Jonny Lee Miller, Ewen Bremner client: TriStar Pictures 2015 Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them director: David Yates cast: Eddie Redmayne, Katherine Waterston, Ezra Miller, Colin Farrell, Samantha Morton client: Warner Bros. -

Camera Operator/ Steadicam Operator

PRINCESTONE ( +44 (0) 208 883 1616 8 [email protected] SIMON BAKER Assoc. BSC / GBCT / ACO Camera Operator/ Steadicam Operator FEATURES: Title Director / DOP Production Co BLITHE SPIRIT Edward Hall / Fred Films / Powderkeg Pictures / B Camera operator / Steadicam Ed Wilde Align Cast: Emilia Fox, Isla Fisher, Judy Dench, Dan Stevens DOWNTON ABBEY Michael Engler / Carnival Films / Focus Features / B Camera operator / Steadicam Ben Smithard Perfect World Pictures Cast: Hugh Bonneville, Matthew Goode, Maggie Smith, Michelle Dockerty,Tuppence Middleton PETER RABBIT 2 (UK Unit) Will Gluck / Sony Pictures / B Camera Operator Peter Menzies Jnr Rose Line Productions Cast: Domhnall Gleeson, Rose Byrne, James Corden HIS HOUSE Remi Weekes / New Regency / BBC Films Camera operator / Steadicam Jo Willems Cast: Sope Dirisu, Munmi Mosaku, Matt Smith FANTASTIC BEASTS: CRIMES OF GRINDLEWALD Stephen Woolfenden / Warner Bros 2nd Unit B camera /Steadicam Jean-Phillippe Gossart A&B camera/ Steadicam on Main Unit David Yates / Phillipe Rousselot Cast: Eddie Redmayne, Johnny Depp ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Ridley Scott / Sony / Tristar / Imperative / B camera operator (2wks reshoots) Darius Wolski Scott Free Productions Cast: Christopher Plummer, Michelle Williams PETER RABBIT (UK Unit) Will Gluck / Columbia Pictures / B camera operator Peter Menzies Jnr Animal Logic Ent. Cast: Domhnall Gleeson, Rose Byrne, James Corden THE MAN WHO INVENTED CHRISTMAS Bharat Nalluri / Thunderbird / Bleeker Street B camera operator / Steadicam Ben Smithard Cast: Dan Stevens, -

INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS) - MASTER MATRIX Features

Work Package 2 Text analysis and development WP Leader: Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Anna Maszerowska Anna Matamala Pilar Orero Date: 8/2/2013 This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This report reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. Work Package 2 Deliverable 1. Introduction After gathering all the information regarding user needs, and detailed information abut audio description in Europe from WP1. This WP expects to go beyond that which has already been investigated, but only partially answered, with regard to What can be described? What should be described – scenes, characters, plot? What should not be described? How objective should the description be? What register of language should be adopted on what occasions? Thus the early objective, having taken stock of all that is valid in the current situation across Europe, in this WP we go further into the questions raised above and find criteria that will be useful across all language combinations and all kinds of material to be described ranging from film to opera to live events such as royal weddings. The use of eye-tracking technology, psychological studies and systemic linguistic investigation are examples of the kind of innovative approaches that will be brought to bear. Under WP2 (text analysis and development) all partners carried out extensive text analysis on a unique text. This is the first deviation from the original project proposal approved. After much debate amongst partners in face to face meetings (Munich March 2012) and the weekly online meetings (Mondays) it was decided to look for one common text which may contain most genres and problems. -

Emma Watson Talks About 'Harry Potter and the Deathly Hollows'

Photo By: Helen Krovski Emma Watson Talks About ‘Harry Potter and the Deathly Hollows’ By: Rebecca Murray mma Watson began the Harry Potter series as a fresh-faced, wild-haired big screen newcomer. Now with the final film finished shooting, the seventh film hitting theaters and only one more left Eto promote, Watson is thankful for the experience but ready to move on with life. She’s currently enrolled at Brown University and is enjoying her time as a college student. Though she had to take a couple of weeks off from her studies in order to promote Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, she’s look- ing forward to maybe working on a film a year—if that—and having as normal a college experience as possible. We didn’t make it to London for this year’s press junket for Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 1, but Warner Bros shared audio files from the next to last press tour for theHarry Potter franchise. Here are some of Emma Watson’s key answers regarding life on the set of Deathly Hallows, kissing her co-stars, and shooting that final Harry Potter scene. 2 — about Entertainment On Harry, Ron, and Hermione: Emma Watson: “You know, it was so nice not having that whole infrastructure of having the castle and the school year. As much as it’s been “The thing about working with amazing to work with all the talent, it can become quite stilted having all these kind of like barriers in David Yates is you always hear this place. -

I Am Not Your Negro

Magnolia Pictures and Amazon Studios Velvet Film, Inc., Velvet Film, Artémis Productions, Close Up Films In coproduction with ARTE France, Independent Television Service (ITVS) with funding provided by Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), RTS Radio Télévision Suisse, RTBF (Télévision belge), Shelter Prod With the support of Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image Animée, MEDIA Programme of the European Union, Sundance Institute Documentary Film Program, National Black Programming Consortium (NBPC), Cinereach, PROCIREP – Société des Producteurs, ANGOA, Taxshelter.be, ING, Tax Shelter Incentive of the Federal Government of Belgium, Cinéforom, Loterie Romande Presents I AM NOT YOUR NEGRO A film by Raoul Peck From the writings of James Baldwin Cast: Samuel L. Jackson 93 minutes Winner Best Documentary – Los Angeles Film Critics Association Winner Best Writing - IDA Creative Recognition Award Four Festival Audience Awards – Toronto, Hamptons, Philadelphia, Chicago Two IDA Documentary Awards Nominations – Including Best Feature Five Cinema Eye Honors Award Nominations – Including Outstanding Achievement in Nonfiction Feature Filmmaking and Direction Best Documentary Nomination – Film Independent Spirit Awards Best Documentary Nomination – Gotham Awards Distributor Contact: Press Contact NY/Nat’l: Press Contact LA/Nat’l: Arianne Ayers Ryan Werner Rene Ridinger George Nicholis Emilie Spiegel Shelby Kimlick Magnolia Pictures Cinetic Media MPRM Communications (212) 924-6701 phone [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 49 west 27th street 7th floor new york, ny 10001 tel 212 924 6701 fax 212 924 6742 www.magpictures.com SYNOPSIS In 1979, James Baldwin wrote a letter to his literary agent describing his next project, Remember This House. -

A Look Into the South According to Quentin Tarantino Justin Tyler Necaise University of Mississippi

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2018 The ineC matic South: A Look into the South According to Quentin Tarantino Justin Tyler Necaise University of Mississippi. Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Necaise, Justin Tyler, "The ineC matic South: A Look into the South According to Quentin Tarantino" (2018). Honors Theses. 493. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/493 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CINEMATIC SOUTH: A LOOK INTO THE SOUTH ACCORDING TO QUENTIN TARANTINO by Justin Tyler Necaise A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford May 2018 Approved by __________________________ Advisor: Dr. Andy Harper ___________________________ Reader: Dr. Kathryn McKee ____________________________ Reader: Dr. Debra Young © 2018 Justin Tyler Necaise ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii To Laney The most pure-hearted person I have ever met. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to my family for being the most supportive group of people I could have ever asked for. Thank you to my father, Heath, who instilled my love for cinema and popular culture and for shaping the man I am today. Thank you to my mother, Angie, who taught me compassion and a knack for looking past the surface to see the truth that I will carry with me through life. -

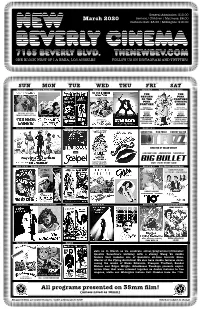

Newbev202003 FRONT

General Admission: $12.00 March 2020 Seniors / Children / Matinees: $8.00 NEW Cartoon Club: $8.00 / Midnights: $10.00 BEVERLY cinema 7165 BEVERLY BLVD. THENEWBEV.COM ONE BLOCK WEST OF LA BREA, LOS ANGELES FOLLOW US ON INSTAGRAM AND TWITTER! SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT March 1 & 2 Directed by Randal Kleiser March 3 March 4 & 5 March 6 & 7 Blake Edwards / Peter Sellers THE THE RETURN PINK OF THE PANTHER PINK STRIKES PANTHER AGAIN DIRECTED BY DIRECTED BY BLAKE EDWARDS BLAKE EDWARDS STARRING STARRING BROOKE SHIELDS PETER PETER CHRISTOPHER ATKINS SELLERS SELLERS CHRISTOPHER HERBERT LOM JOHN HUSTON’S PLUMMER COLIN BLAKELY CATHERINE SCHELL LEONARD ROSSITER HERBERT LOM LESLEY-ANNE DOWN March 8 & 9 Directed by Blake Edwards March 10 March 11 & 12 March 13 & 14 SIMON PEGG NICK FROST TIMOTHY DALTON DIRECTED BY EDGAR WRIGHT PLUS! BIGLAU CHING-WAN BULLET JORDAN CHAN THERESA LEE UGO TOGNAZZI MICHEL SERRAULT DIRECTED BY BENNY CHAN March 15 & 16 Barbara Stanwyck Double Feature March 17 March 18 & 19 March 20 & 21 Blake Edwards / Dudley Moore DUDLEY MOORE AMY IRVING ANN REINKING DUDLEY MOORE JULIE ANDREWS BO DEREK March 22 & 23 Directed by François Truffaut March 24 March 25 & 26 March 27 & 28 Quentin’s Birthday Double Feature JIMMY WANG YU Written, Directed by, and Starring Written & Directed by JIMMY WANG YU LO WEI March 29 & 30 March 31 Join us in March as we celebrate owner/programmer/fi lmmaker Quentin Tarantino’s birthday with a Jimmy Wang Yu double IB Tech Print feature that includes one of Quentin’s all-time favorite fi lms, IB Tech Print Master of the Flying Guillotine! We also have double features show- casing the works of Blake Edwards, François Truff aut, Randal Kleiser and Edgar Wright. -

Quentin Tarantino : the Iconic Filmmaker and His Work Pdf, Epub, Ebook

QUENTIN TARANTINO : THE ICONIC FILMMAKER AND HIS WORK PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Ian Nathan | 176 pages | 05 Dec 2019 | AURUM PRESS | 9781781317754 | English | London, United Kingdom Quentin Tarantino : The iconic filmmaker and his work PDF Book Each prestigious golf resort is presented with an expert review, covering its benefits on and off the fairways and greens. Sep 30, Richard rated it really liked it. I think I hear a symphony. A book like this, aimed at popular readership, demands large full color pictures and a dynamic look. Connie pushed the greats on him, but he gravitated to crime fiction. Aug 07, Janet rated it really liked it Shelves: artsy-crunchygranola , zzng-when- i-read , k-e-k. There beneath the smoky projector beam he first saw the genre-twisting dreams of Jean-Luc Godard, which moved him so very deeply. Error rating book. Other Editions 1. Nathan tackles all of Tarantino's movies and screenplays, which could make for a fascinating panorama, but as this is a short book, there is not much depth or structure to the analysis. Get to know the cult filmmaker of our generation. This is the ultimate celebration for any Tarantino fan. What clothes would they want to wear? Late in her pregnancy, Connie Tarantino — henceforth the redoubtable 'Connie' — became hooked on the Western serial 'Gunsmoke', featuring a young Burt Reynolds as Quint Asper, the half-Comanche blacksmith who appeared for three seasons. Your Cookie Preferences We use different types of cookies to optimize your experience on our website. Meanwhile, Tarantino switched acting classes. Remember me? In other words, the tenderfoot Tarantino did not go wanting. -

Inglourious Basterds' Premiere

id Software's Wolfenstein™ to Co-Sponsor the 'Inglourious Basterds' Premiere --Historic Gaming Franchise Set to Join Forces with Quentin Tarantino to Fight the Third Reich SANTA MONICA, Calif., July 28, 2009 /PRNewswire-FirstCall via COMTEX News Network/ -- Activision Publishing (Nasdaq: ATVI) and id Software have signed-on for the highly-anticipated Wolfenstein to be a title sponsor of The Weinstein Company and Universal Pictures International's upcoming feature film by Quentin Tarantino, "Inglourious Basterds." As an official sponsor, Activision will conduct a contest for two lucky winners to attend the "Inglourious Basterds" Hollywood premier at the historic Grauman's Chinese Theater on August 10. The prize pack includes two roundtrip tickets for a four day - three night stay in Los Angeles, two tickets to the premier and two tickets to the star-studded after party at Mondrian in West Hollywood. Check http://www.GameSpot.com for contest details, which begins today. The assault on the Third Reich kicks-off with the newest chapter of the famed Wolfenstein franchise hitting U.S. store shelves on August 18, and a second wave continues the fight with "Inglourious Basterds" going nation-wide in theaters August 21. About Wolfenstein Wolfenstein brings the Nazi's dark obsession with the occult to life, by intertwining fast-paced, intense story-driven combat with a diverse sci-fi experience. As BJ Blazkowicz, a highly decorated member of the Office of Secret Actions (OSA), you are sent on a special mission into the heart of the Third Reich to investigate evidence that the SS hierarchy may possess a new and mysterious power.