A Study of D'orbigny's “Voyage Dans L'amerique

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Generic Distinction of Pied Woodpeckers

THE GENERIC DISTINCTION OF PIED WOODPECKERS M. RALPH BROWNING, 170 JacksonCreek Drive, Jacksonville,Oregon 97530 ABSTRACT: The ten speciesof New World four-toedwoodpeckers (scalaris, nuttallii, pubescens, villosus, stricklandi, arizonae, borealis, albolarvatus, lignarius,and m ixtusand the two borealthree-toed species (arcticus and tridactylus), currentlycombined in the genusPicoides, differ, in additionto the numberof toes,in modificationsof the skull,ribs, the belly of the pubo-ischio-femoralismuscle, head plumage,and behavior. I recommendthat the genericname Dryobates be reinstituted for the New World four-toedwoodpeckers. There are three generalmorphological groups of pied woodpeckers,a groupof nine four-toedspecies of the New World, a groupof 22 four-toed speciesof the Old World, and a groupof two three-toedspecies straddling bothregions. ! referto thesegroups of piedwoodpeckers beyond as the New World,Old World,and three-toedgroups. The three-toedspecies have long beenin the genusPicoides Lac•p•de, 1799, but the four-toedgroups have been combinedat the genericlevel in differentways. All four-toedpied woodpeckerswere long includedin the genusDryobates Boie, 1826, later changed to Dendrocopos Koch, 1816 an earlier name (Voous 1947, A.O.U. 1947, Peters 1948). Despite the differencein number of toes, Dendrocoposwas combined with Picoidesbecause of generalsimilarities in anatomy (Delacour 1951, Short 1971a), plumage and behavior (Short 1974a), and vocalizations(Winkler and Short 1978). The A.O.U (1976) followedthis mergerof the genera.On the basisof skeletalcharacters Rea (1983) was skepticalof the merger,but he did not providedetails. On the otherhand, Ouellet(1977), concludingthat the two generadiffer in external morphologyand some behaviors and vocalizations, separated the Old World four-toedwoodpeckers in Dendrocoposand three-toedand New World four-toedwoodpeckers in Picoides.The A.O.U. -

Southeast Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna, Oct-Nov 2016

Tropical Birding Trip Report Southeast Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna, Oct-Nov 2016 SOUTHEAST BRAZIL: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna October 20th – November 8th, 2016 TOUR LEADER: Nick Athanas Report and photos by Nick Athanas Helmeted Woodpecker - one of our most memorable sightings of the tour It had been a couple of years since I last guided this tour, and I had forgotten how much fun it could be. We covered a lot of ground and visited a great series of parks, lodges, and reserves, racking up a respectable group list of 459 bird species seen as well as some nice mammals. There was a lot of rain in the area, but we had to consider ourselves fortunate that the rainiest days seemed to coincide with our long travel days, so it really didn’t cost us too much in the way of birds. My personal trip favorite sighting was our amazing and prolonged encounter with a rare Helmeted Woodpecker! Others of note included extreme close-ups of Spot-winged Wood-Quail, a surprise Sungrebe, multiple White-necked Hawks, Long-trained Nightjar, 31 species of antbirds, scope views of Variegated Antpitta, a point-blank Spotted Bamboowren, tons of colorful hummers and tanagers, TWO Maned Wolves at the same time, and Giant Anteater. This report is a bit light on text and a bit heavy of photos, mainly due to my insane schedule lately where I have hardly had any time at home, but all photos are from the tour. www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Tropical Birding Trip Report Southeast Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna, Oct-Nov 2016 The trip started in the city of Curitiba. -

IGUAZU FALLS Extension 1-15 December 2016

Tropical Birding Trip Report NW Argentina & Iguazu Falls: December 2016 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour NW ARGENTINA: High Andes, Yungas and Monte Desert and IGUAZU FALLS Extension 1-15 December 2016 TOUR LEADER: ANDRES VASQUEZ (All Photos by Andres Vasquez) A combination of breathtaking landscapes and stunning birds are what define this tour. Clockwise from bottom left: Cerro de los 7 Colores in the Humahuaca Valley, a World Heritage Site; Wedge-tailed Hillstar at Yavi; Ochre-collared Piculet on the Iguazu Falls Extension; and one of the innumerable angles of one of the World’s-must-visit destinations, Iguazu Falls. www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] p.1 Tropical Birding Trip Report NW Argentina & Iguazu Falls: December 2016 Introduction: This is the only tour that I guide where I feel that the scenery is as impressive (or even surpasses) the birds themselves. This is not to say that the birds are dull on this tour, far from it. Some of the avian highlights included wonderfully jeweled hummingbirds like Wedge-tailed Hillstar and Red-tailed Comet; getting EXCELLENT views of 4 Tinamou species of, (a rare thing on all South American tours except this one); nearly 20 species of ducks, geese and swans, with highlights being repeated views of Torrent Ducks, the rare and oddly, parasitic Black-headed Duck, the beautiful Rosy-billed Pochard, and the mountain-dwelling Andean Goose. And we should not forget other popular bird features like 3 species of Flamingos on one lake, 11 species of Woodpeckers, including the hulking Cream-backed, colorful Yellow-fronted and minuscule Ochre-collared Piculet on the extension to Iguazu Falls. -

Supplemental Wing Shape and Dispersal Analysis

Data Supplement High dispersal ability inhibits speciation in a continental radiation of passerine birds Santiago Claramunt, Elizabeth P. Derryberry, J. V. Remsen, Jr. & Robb T. Brumfield Museum of Natural Science and Department of Biological Sciences, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803, USA HAND-WING INDEX AND FLIGHT PERFORMANCE IN NEOTROPICAL FOREST BIRDS We investigated the relationship between wing shape and flight distances determined during 'dispersal challenge' experiments conducted in Gatun Lake in the Panama Canal (Moore et al. 2008). During the experiments, birds were released from a boat at incremental distances from shore and the distance flown or the success or failure in reaching the coast was recorded. To investigated the relationship between the hand-wing index and flight distance in Neotropical birds we used data on mean distance flown from table 3 in ref. We estimated hand-wing indices for the 10 species reported in those experiments (Table S1) . Wing measurements were taken by SC for four males of each species at LSUMNS. The relationship between the hand-wing index and distance flown was evaluated statistically using phylogenetic generalized least-squares (PGLS, Freckleton et al. 2002). We generated a phylogeny for the species involved in the experiment or an appropriate surrogate using DNA sequences of the slow-evolving RAG 1 gene from GenBank (Table S2). A maximum likelihood ultrametric tree was generated in PAUP* (Swofford 2003) using a GTR+! model of nucleotide substitution rates, empirical nucleotide frequencies, and enforcing a molecular clock. We found that the hand-wing index was strongly related to mean distance flown (R2 = 0.68, F = 20, d.f. -

Evolution of the Ovenbird-Woodcreeper Assemblage (Aves: Furnariidae) Б/ Major Shifts in Nest Architecture and Adaptive Radiatio

JOURNAL OF AVIAN BIOLOGY 37: 260Á/272, 2006 Evolution of the ovenbird-woodcreeper assemblage (Aves: Furnariidae) / major shifts in nest architecture and adaptive radiation Á Martin Irestedt, Jon Fjeldsa˚ and Per G. P. Ericson Irestedt, M., Fjeldsa˚, J. and Ericson, P. G. P. 2006. Evolution of the ovenbird- woodcreeper assemblage (Aves: Furnariidae) Á/ major shifts in nest architecture and adaptive radiation. Á/ J. Avian Biol. 37: 260Á/272 The Neotropical ovenbirds (Furnariidae) form an extraordinary morphologically and ecologically diverse passerine radiation, which includes many examples of species that are superficially similar to other passerine birds as a resulting from their adaptations to similar lifestyles. The ovenbirds further exhibits a truly remarkable variation in nest types, arguably approaching that found in the entire passerine clade. Herein we present a genus-level phylogeny of ovenbirds based on both mitochondrial and nuclear DNA including a more complete taxon sampling than in previous molecular studies of the group. The phylogenetic results are in good agreement with earlier molecular studies of ovenbirds, and supports the suggestion that Geositta and Sclerurus form the sister clade to both core-ovenbirds and woodcreepers. Within the core-ovenbirds several relationships that are incongruent with traditional classifications are suggested. Among other things, the philydorine ovenbirds are found to be non-monophyletic. The mapping of principal nesting strategies onto the molecular phylogeny suggests cavity nesting to be plesiomorphic within the ovenbirdÁ/woodcreeper radiation. It is also suggested that the shift from cavity nesting to building vegetative nests is likely to have happened at least three times during the evolution of the group. -

AOS Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2018-B 17 January 2018

AOS Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2018-B 17 January 2018 No. Page Title 01 02 Split Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus into four species 02 05 Restore Canada Jay as the English name of Perisoreus canadensis 03 13 Recognize two genera in Stercorariidae 04 15 Split Red-eyed Vireo (Vireo olivaceus) into two species 05 19 Split Pseudobulweria from Pterodroma 06 25 Add Tadorna tadorna (Common Shelduck) to the Checklist 07 27 Add three species to the U.S. list 08 29 Change the English names of the two species of Gallinula that occur in our area 09 32 Change the English name of Leistes militaris to Red-breasted Meadowlark 10 35 Revise generic assignments of woodpeckers of the genus Picoides 11 39 Split the storm-petrels (Hydrobatidae) into two families 1 2018-B-1 N&MA Classification Committee p. 280 Split Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus into four species Effect on NACC: This proposal would change the species circumscription of Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus by splitting it into four species. The form that occurs in the NACC area is nominate pacificus, so the current species account would remain unchanged except for the distributional statement and notes. Background: The Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus was until recently (e.g., Chantler 1999, 2000) considered to consist of four subspecies: pacificus, kanoi, cooki, and leuconyx. Nominate pacificus is highly migratory, breeding from Siberia south to northern China and Japan, and wintering in Australia, Indonesia, and Malaysia. The other subspecies are either residents or short distance migrants: kanoi, which breeds from Taiwan west to SE Tibet and appears to winter as far south as southeast Asia. -

Woodpeckers and Allies)

Coexistence, Ecomorphology, and Diversification in the Avian Family Picidae (Woodpeckers and Allies) A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Matthew Dufort IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY F. Keith Barker and Kenneth Kozak October 2015 © Matthew Dufort 2015 Acknowledgements I thank the many people, named and unnamed, who helped to make this possible. Keith Barker and Ken Kozak provided guidance throughout this process, engaged in innumerable conversations during the development and execution of this project, and provided invaluable feedback on this dissertation. My committee members, Jeannine Cavender-Bares and George Weiblen, provided helpful input on my project and feedback on this dissertation. I thank the Barker, Kozak, Jansa, and Zink labs and the Systematics Discussion Group for stimulating discussions that helped to shape the ideas presented here, and for insight on data collection and analytical approaches. Hernán Vázquez-Miranda was a constant source of information on lab techniques and phylogenetic methods, shared unpublished PCR primers and DNA extracts, and shared my enthusiasm for woodpeckers. Laura Garbe assisted with DNA sequencing. A number of organizations provided financial or logistical support without which this dissertation would not have been possible. I received fellowships from the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program and the Graduate School Fellowship of the University of Minnesota. Research funding was provided by the Dayton Fund of the Bell Museum of Natural History, the Chapman Fund of the American Museum of Natural History, the Field Museum of Natural History, and the University of Minnesota Council of Graduate Students. -

Threatened Birds of the Americas

GREY-HEADED ANTBIRD Myrmeciza griseiceps E2 This rare formicariid is confined to patches of bamboo and dense undergrowth in semi-deciduous moist forest and cloud-forest in the Pacific slope foothills of the Andes in south-west Ecuador and north-west Peru, where it is threatened by habitat destruction. DISTRIBUTION The Grey-headed Antbird (see Remarks 1) is confined to the Pacific slope of the Andes in El Oro and Loja provinces, south-west Ecuador, and Tumbes and Piura departments, north-west Peru, where it is found at elevations ranging from 600 to 2,900 m. The bird is known from few specimens, and is generally distributed in five areas, where localities (coordinates from Paynter and Traylor 1977 and Stephens and Traylor 1983) are as follows: Ecuador (El Oro) La Chonta, 610 m (Chapman 1926, Zimmer 1932), at 3°35’S 79°53’W (see Remarks 2); San Pablo, 1,200 m, at 3°41’S 79°33’W, near Zaruma, where a bird (possibly this species) was heard calling in 1991 (Williams and Tobias 1991); (Loja) above Vicentino, 1,250-1,450 m, at c.3°56’S 79°55’W (five males singing in February 1991: Best 1992); Alamor, 1,400 m (Chapman 1926) at 4°02’S 80°02’W; Celica, 2,100 m (Zimmer 1932) at 4°07’S 79°59’W; 8 km west of Celica, 1,900 m (one specimen collected and others seen in August 1989: R. S. Ridgely in litt. 1989); near San José de Pozul along the road to Pindal, 1,600 m, at 4°07’S 80°03’W (sightings in April–May 1989: P. -

Phylogenetic Analysis of the Nest Architecture of Neotropical Ovenbirds (Furnariidae)

The Auk 116(4):891-911, 1999 PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSIS OF THE NEST ARCHITECTURE OF NEOTROPICAL OVENBIRDS (FURNARIIDAE) KRZYSZTOF ZYSKOWSKI • AND RICHARD O. PRUM NaturalHistory Museum and Department of Ecologyand Evolutionary Biology, University of Kansas,Lawrence, Kansas66045, USA ABSTRACT.--Wereviewed the tremendousarchitectural diversity of ovenbird(Furnari- idae) nestsbased on literature,museum collections, and new field observations.With few exceptions,furnariids exhibited low intraspecificvariation for the nestcharacters hypothe- sized,with the majorityof variationbeing hierarchicallydistributed among taxa. We hy- pothesizednest homologies for 168species in 41 genera(ca. 70% of all speciesand genera) and codedthem as 24 derivedcharacters. Forty-eight most-parsimonious trees (41 steps,CI = 0.98, RC = 0.97) resultedfrom a parsimonyanalysis of the equallyweighted characters using PAUP,with the Dendrocolaptidaeand Formicarioideaas successiveoutgroups. The strict-consensustopology based on thesetrees contained 15 cladesrepresenting both tra- ditionaltaxa and novelphylogenetic groupings. Comparisons with the outgroupsdemon- stratethat cavitynesting is plesiomorphicto the furnariids.In the two lineageswhere the primitivecavity nest has been lost, novel nest structures have evolved to enclosethe nest contents:the clayoven of Furnariusand the domedvegetative nest of the synallaxineclade. Althoughour phylogenetichypothesis should be consideredas a heuristicprediction to be testedsubsequently by additionalcharacter evidence, this first cladisticanalysis -

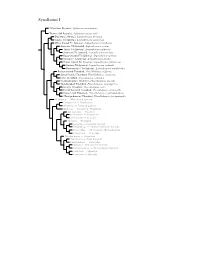

Synallaxini Species Tree

Synallaxini I ?Masafuera Rayadito, Aphrastura masafuerae Thorn-tailed Rayadito, Aphrastura spinicauda Des Murs’s Wiretail, Leptasthenura desmurii Tawny Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura yanacensis White-browed Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura xenothorax Araucaria Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura setaria Tufted Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura platensis Striolated Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura striolata Rusty-crowned Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura pileata Streaked Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura striata Brown-capped Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura fuliginiceps Andean Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura andicola Plain-mantled Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura aegithaloides Rufous-fronted Thornbird, Phacellodomus rufifrons Streak-fronted Thornbird, Phacellodomus striaticeps Little Thornbird, Phacellodomus sibilatrix Chestnut-backed Thornbird, Phacellodomus dorsalis Spot-breasted Thornbird, Phacellodomus maculipectus Greater Thornbird, Phacellodomus ruber Freckle-breasted Thornbird, Phacellodomus striaticollis Orange-eyed Thornbird, Phacellodomus erythrophthalmus ?Orange-breasted Thornbird, Phacellodomus ferrugineigula Hellmayrea — White-tailed Spinetail Coryphistera — Brushrunner Anumbius — Firewood-gatherer Asthenes — Canasteros, Thistletails Acrobatornis — Graveteiro Metopothrix — Plushcrown Xenerpestes — Graytails Siptornis — Prickletail Roraimia — Roraiman Barbtail Thripophaga — Speckled Spinetail, Softtails Limnoctites — ST Spinetail, SB Reedhaunter Cranioleuca — Spinetails Pseudasthenes — Canasteros Spartonoica — Wren-Spinetail Pseudoseisura — Cacholotes Mazaria – White-bellied -

Download File

Natural selection and demography shape the genomes of New World birds Lucas Rocha Moreira Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2021 © 2021 Lucas Rocha Moreira All Rights Reserved Abstract Natural selection and demography shape the genomes of New World birds Lucas Rocha Moreira Genomic diversity is shaped by the interplay between mutation, genetic drift, recombination, and natural selection. A major goal of evolutionary biology is to understand the relative contribution of these different microevolutionary forces to patterns of genetic variation both within and across species. The advent of massive parallel sequencing technologies opened new avenues to investigate the extent to which alternative evolutionary mechanisms impact the genome and the footprints they leave. We can leverage genomic information to, for example, trace back the demographic trajectory of populations and to identify genomic regions underlying adaptive traits. In this disser- tation, I employ genomic data to explore the role of demography and natural selection in two New World bird systems distributed along steep environmental gradients: the Altamira Oriole (Icterus gularis), a Mesoamerican bird that exhibits large variation in body size across its range, and the Hairy and Downy woodpecker (Dryobates villosus and D. pubescens), two sympatric species whose phenotypes vary extensively in response to environments in North America. In Chapter 1, I combine ecological niche model, phenotypic and ddRAD sequencing data from several individuals of I. gularis to investigate which spatial processes best explain geographic variation in phenotypes and alleles: (i) isolation by distance, (ii) isolation by history or (iii) isolation by environment. -

Geographic Variation, Zoogeography, and Possible Rapid Evolution in Some Cranioleuca Spinetails (Furnariidae) of the Andes

THE WILSON BULLETIN A QUARTERLY MAGAZINE OF ORNITHOLOGY Published by the Wilson Ornithological Society VOL. 96, No. 4 DECEMBER 1984 PAGES 5 15-775 Wilson Bull., 96(4), 1984, pp. 5 15-523 GEOGRAPHIC VARIATION, ZOOGEOGRAPHY, AND POSSIBLE RAPID EVOLUTION IN SOME CRANIOLEUCA SPINETAILS (FURNARIIDAE) OF THE ANDES J. V. REMSEN, JR. The humid slopes of the Andes Mountains of South America provide one of the worlds’ greatest natural laboratories for the study of evolution and zoogeography. Although the “population structure,” nature of geo- graphic variation, and location of zoogeographic boundaries have been described for numerous taxa of the puna and paramo zones of the Andes (Vuilleumier 1980) relatively little has been published concerning birds of the humid, forested eastern slopes. In this paper, I analyze the geo- graphic variation and distribution of the Cranioleuca albiceps superspe- ties (Fumariidae), here considered to consist of Light-crowned Spinetail (C. a/biceps) (with two subspecies), Marcapata Spinetail (C. marcapatae), and a previously undescribed form, here considered a subspecies of C. marcapatae, to be called: Cranioleuca marcapatae weskeisubsp. nov. HOLOTYPE.-American Museum of Natural History No. 820557; male from Cordillera Vilcabamba, elev. 3250 m, Dpto. Cuzco, Peru (12”36S,’ 733O’ W),’ 22 July 1968; John S. Weske, original number 1825. DIAGNOSIS.-Ventrally very similar to Crunioleuca m. marcupatae, but malar region more strongly washed buff; dorsally, virtually identical to white-crowned individuals of Cranioleuca a.