White Paper Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tom Thumb Comes to Town

TOM THUMB COMES TO TOWN By Marianne G. Morrow The Performance Tom Thumb had already performed twice in Hali- ver the years, the city of Char- fax, in 1847 and 1850, O lottetown has had many exotic but he had never come visitors, from British royalty t o gangsters. to Prince Edward Perhaps the most unusual, though, was Island. His visit in 1868 the celebrated "General" Tom Thumb probably followed a set and his troupe of performers. On 30 July pattern. The group's 1868, Tom Thumb, his wife Lavinia "Director of Amuse- Warren, her sister Minnie, and "Commo- ments" was one Sylvester dore" Nutt arrived fresh from a European Bleecker, but advance pub- tour to perform in the Island capital's licity was handled by a local Market Hall. agent, Ned Davies. There Tom Thumb was a midget, as would be five performances were the other members of his com- spread over a two-day period. pany. Midgets differ from dwarfs in "Ladies and children are con- that they are perfectly proportioned siderately advised to attend the beings, "beautiful and symmetri- Day exhibition, and thus avoid cally formed ladies and gentlemen the crowd and confusion of the in miniature," as the ads for evening performances." Thumb's performance promised. S The pitch was irresistible. What society considered a disability, \ "The Smallest Human Beings of Tom Thumb had managed to turn 1 Mature Age Ever Known on the into a career. By the time he arrived S Face of the Globe!" boasted one on Prince Edward Island, he had been 4 ad. -

Barnum Museum, Planning to Digitize the Collections

Narrative Section of a Successful Application The attached document contains the grant narrative of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful application may be crafted. Every successful application is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the NEH Division of Preservation and Access application guidelines at http://www.neh.gov/grants/preservation/humanities-collections-and-reference- resources for instructions. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Preservation and Access staff well before a grant deadline. Note: The attachment only contains the grant narrative, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: Planning for "The Greatest Digitization Project on Earth" with the P. T. Barnum Collections of The Barnum Museum Foundation Institution: Barnum Museum Project Director: Adrienne Saint Pierre Grant Program: Humanities Collections and Reference Resources 1100 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W., Rm. 411, Washington, D.C. 20506 P 202.606.8570 F 202.606.8639 E [email protected] www.neh.gov The Barnum Museum Foundation, Inc. Application to the NEH/Humanities Collections and Reference Resources Program Narrative Significance Relevance of the Collections to the Humanities Phineas Taylor Barnum's impact reaches deep into our American heritage, and extends far beyond his well-known circus enterprise, which was essentially his “retirement project” begun at age sixty-one. -

Five Points Book by Harrison David Rivers Music by Ethan D

Please join us for a Post-Show Discussion immediately following this performance. Photo by Allen Weeks by Photo FIVE POINTS BOOK BY HARRISON DAVID RIVERS MUSIC BY ETHAN D. PAKCHAR & DOUGLAS LYONS LYRICS BY DOUGLAS LYONS DIRECTED BY PETER ROTHSTEIN MUSIC DIRECTION BY DENISE PROSEK CHOREOGRAPHY BY KELLI FOSTER WARDER WORLD PREMIERE • APRIL 4 - MAY 6, 2018 • RITZ THEATER Theater Latté Da presents the world premiere of FIVE POINTS Book by Harrison David Rivers Music by Ethan D. Pakchar & Douglas Lyons Lyrics by Douglas Lyons Directed by Peter Rothstein** Music Direction by Denise Prosek† Choreography by Kelli Foster Warder FEATURING Ben Bakken, Dieter Bierbrauer*, Shinah Brashears*, Ivory Doublette*, Daniel Greco, John Jamison, Lamar Jefferson*, Ann Michels*, Thomasina Petrus*, T. Mychael Rambo*, Matt Riehle, Kendall Anne Thompson*, Evan Tyler Wilson, and Alejandro Vega. *Member of Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of Professional Actors ** Member of SDC, the Stage Directors and Choreographers Society, a national theatrical labor union †Member of Twin Cities Musicians Union, American Federation of Musicians FIVE POINTS will be performed with one 15-minute intermission. Opening Night: Saturday, April 7, 2018 ASL Interpreted and Audio Described Performance: Thursday, April 26, 2018 Meet The Writers: Sunday, April 8, 2018 Post-Show Discussions: Thursdays April 12, 19, 26, and May 3 Sundays April 11, 15, 22, 29, and May 6 This production is made possible by special arrangement with Marianne Mills and Matthew Masten. The videotaping or other video or audio recording of this production is strictly prohibited. As a courtesy to the performers and other patrons, please check to see that all cell phones, pagers, watches, and other noise-making devices are turned off. -

A Description of the Main Characters in the Movie the Greatest Showman

A DESCRIPTION OF THE MAIN CHARACTERS IN THE MOVIE THE GREATEST SHOWMAN A PAPER BY ELVA RAHMI REG.NO: 152202024 DIPLOMA III ENGLISH DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF CULTURE STUDY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH SUMATERA MEDAN 2018 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA AUTHOR’S DECLARATION I am ELVA RAHMI, declare that I am the sole author of this paper. Except where reference is made in the text of this paper, this paper contains no material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or in part from a paper by which I have qualified for or awarded another degree. No other person’s work has been used without due acknowledgement in the main text of this paper. This paper has not been submitted for the award of another degree in any tertiary education. Signed : ……………. Date : 2018 i UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA COPYRIGHT DECLARATION Name: ELVA RAHMI Title of Paper: A DESCRIPTION OF THE MAIN CHARACTERS IN THE MOVIE THE GREATEST SHOWMAN. Qualification: D-III / Ahli Madya Study Program : English 1. I am willing that my paper should be available for reproduction at the discretion of the Libertarian of the Diploma III English Faculty of Culture Studies University of North Sumatera on the understanding that users are made aware of their obligation under law of the Republic of Indonesia. 2. I am not willing that my papers be made available for reproduction. Signed : ………….. Date : 2018 ii UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA ABSTRACT The title of this paper is DESCRIPTION OF THE MAIN CHARACTERS IN THE GREATEST SHOWMAN MOVIE. The purpose of this paper is to find the main character. -

Barnum Institute of Science and History" in Low Relief

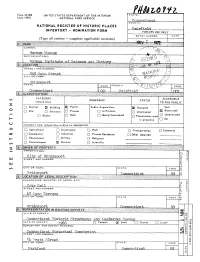

Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE: (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER DATE (Type all entries — complete applicable sections) &ifiif *y tfvtft. pillllii^ COMMON: r^<~~~~ r. , ~T~~~^ Barnum Museum /" ^, -v/\ AND/OR HISTORIC: /fc fttffiNftJ "'^ Barnum. .Institute of s.$-ienp,<? a.nr) History iffifoxv STREET AND NUMBER: ICO'. \ P Rn^ MATTI Street CITY OR TOWN: X%; ^^\^' Brido-fipnrt STATE CODE COUNTY: ^^J 1 I'f'^ \-^ CODE Connecti cut DQ T?n la^isld,,,.,.....,,,,............,. , ,,,,001...... li!l|$pli;!!iieil::!!::!!l!;;! STATUS ACCESSIBLE <c"«o™ ™«t™" TO THE PUBLIC G District 22 Building El Public Public Acquisition: BQ Occupied Yes: ,, . El Restricted G Site G Structure d Private G In Process D Unoccupied *Qsl i in . G Unrestricted G Object D Botn D Being Considerec G Preservation work in progress ' ' PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) G Agricultural G Government G Park 1 | Transportation 1 1 Comments G Commercial G Industrial G Private Residence n Other (Soecify) G Educational G Military G Religious 1 I Entertainment 53 Museum | | Scientific OWNER'S NAME: STATE: City of Bridgeport STREET AND NUMBER: Connecticut CITY OR TOWN: STA1TE: CODE ill .....Bridgeport C onnecticut O<9 COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: COUNTY: Citv Hal 1 STREET AND NUMBER: ^airfield It 1} T.yon Terrace CITY OR TOWN: STA1TE CODE Rridsre-nort p..7T)7iftCtPiffiTh OQ llltl!!!!^ TITUE OF SURVEY: a NUMBERENTRY Connecticut Historic Structures and Landmarks Survey Tl DATE OF SURVEY: -| Q££ r~j Federal Qfl State "G County G L°ca O 73 DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: Z TO CO CO Connecticut. -

CHOPIN and JENNY LIND

Icons of Europe Extract of paper shared with the Fryderyk Chopin Institute and Edinburgh University CHOPIN and JENNY LIND NEW RESEARCH by Cecilia and Jens Jorgensen Brussels, 7 February 2005 Icons of Europe TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 2 2. INFORMATION ON PEOPLE 4 2.1 Claudius Harris 4 2.2 Nassau W. Senior 5 2.3 Harriet Grote 6 2.4 Queen Victoria 7 2.5 Judge Munthe 9 2.6 Jane Stirling 10 2.7 Jenny Lind 15 2.8 Fryderyk Chopin 19 3. THE COVER-UP 26 3.1 Jenny Lind’s memoir 26 3.2 Account of Jenny Lind 27 3.3 Marriage allegation 27 3.4 Friends and family 27 4. CONCLUSIONS 28 ATTACHMENTS A Sources of information B Consultations in Edinburgh and Warsaw C Annexes C1 – C24 with evidence D Jenny Lind’s tour schedule 1848-1849 _______________________________________ Icons of Europe asbl 32 Rue Haute, B-1380 Lasne, Belgium Tel. +32 2 633 3840 [email protected] http://www.iconsofeurope.com The images of this draft are provided by sources listed in Attachments A and C. Further details will be specified in the final version of the research paper. All rights reserved. Copyright © 2003 Icons of Europe, B-1000 Brussels, Belgium. Filed with the United States Copyright Office of the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 1 Icons of Europe 1. INTRODUCTION This paper recapitulates all the research findings developed in 2003-2004 on the final year of Fryderyk Chopin’s life and his relationship with Jenny Lind in 1848-1849. Comments are invited by scholars in preparation for its intended publication as a sequel to the biography, CHOPIN and The Swedish Nightingale (Icons of Europe, Brussels, August 2003). -

Frank Furness Printed by Official Offset Corp

Nineteenth Ce ntury The Magazine of the Victorian Society in America Volume 37 Number 1 Nineteenth Century hhh THE MAGAZINE OF THE VICTORIAN SOCIETY IN AMERICA VOLuMe 37 • NuMBer 1 SPRING 2017 Editor Contents Warren Ashworth Consulting Editor Sara Chapman Bull’s Teakwood Rooms William Ayres A LOST LETTER REVEALS A CURIOUS COMMISSION Book Review Editor FOR LOCkwOOD DE FOREST 2 Karen Zukowski Roberta A. Mayer and Susan Condrick Managing Editor / Graphic Designer Wendy Midgett Frank Furness Printed by Official Offset Corp. PERPETUAL MOTION AND “THE CAPTAIN’S TROUSERS” 10 Amityville, New York Michael J. Lewis Committee on Publications Chair Warren Ashworth Hart’s Parish Churches William Ayres NOTES ON AN OVERLOOkED AUTHOR & ARCHITECT Anne-Taylor Cahill OF THE GOTHIC REVIVAL ERA 16 Christopher Forbes Sally Buchanan Kinsey John H. Carnahan and James F. O’Gorman Michael J. Lewis Barbara J. Mitnick Jaclyn Spainhour William Noland Karen Zukowski THE MAkING OF A VIRGINIA ARCHITECT 24 Christopher V. Novelli For information on The Victorian Society in America, contact the national office: 1636 Sansom Street Philadelphia, PA 19103 (215) 636-9872 Fax (215) 636-9873 [email protected] Departments www.victoriansociety.org 38 Preservation Diary THE REGILDING OF SAINT-GAUDENS’ DIANA Cynthia Haveson Veloric 42 The Bibliophilist 46 Editorial 49 Contributors Jo Anne Warren Richard Guy Wilson 47 Milestones Karen Zukowski A PENNY FOR YOUR THOUGHTS Anne-Taylor Cahill Cover: Interior of richmond City Hall, richmond, Virginia. Library of Congress. Lockwood de Forest’s showroom at 9 East Seventeenth Street, New York, c. 1885. (Photo is reversed to show correct signature and date on painting seen in the overmantel). -

Jenny Lind's Visit to Elizabethtown, April 1851

Jenny Lind’s visit to Elizabethtown, April 1851 Jenny Lind, the Swedish soprano, entertained the townspeople of Elizabethtown during a tour of the United States in April 1851. She had come to United States in September 1850, under a contract with P.T. Barnum to give 150 concerts for $1,000 dollars each. Jenny Lind, or the "Swedish nightingale," as she was known benefited from Barnum's skillful publicity that brought ex- cited crowds flocking to her concerts, and Lind's name was eventually tied to every kind of commodity, from songs to gloves, bonnets, chairs, sofas, and even pianos. Phineas Taylor Barnum (1810-1891), or P.T. Barnum as he was known is one of the most colorful and well known per- sonalities in American history. A consummate showman and entrepreneur, Barnum was famous for bringing both high and low culture to all of America. From the dulcet tones of opera singer Jenny Lind to the bizarre hoax of the Feejee Mermaid, from the clever and quite diminutive General Tom Thumb to Jumbo the Elephant, Barnum's oddities, Barnum in 1851, just spectacles, galas, extravaganzas, and events tickled the before he went on tour fancies, hearts, minds and imaginations of Americans of all with Jenny Lind. ages. On April 4, 1851, after giving a concert in Nashville, Ms. Lind embarked by stagecoach on her journey to Louisville. The trip over the Louisville and Nashville Turnpike required three days. During the trip, while horses were being changed and during overnight stops, she graciously enter- tained the local residents. The night of April 4th was spent at Bell’s Tavern (now Park City). -

Roebling and the Brooklyn Bridge

BOOK SUMMARY She built a monument for all time. Then she was lost in its shadow. Discover the fascinating woman who helped design and construct an American icon, perfect for readers of The Other Einstein. Emily Warren Roebling refuses to live conventionally―she knows who she is and what she wants, and she's determined to make change. But then her husband Wash asks the unthinkable: give up her dreams to make his possible. Emily's fight for women's suffrage is put on hold, and her life transformed when Wash, the Chief Engineer of the Brooklyn Bridge, is injured on the job. Untrained for the task, but under his guidance, she assumes his role, despite stern resistance and overwhelming obstacles. Lines blur as Wash's vision becomes her own, and when he is unable to return to the job, Emily is consumed by it. But as the project takes shape under Emily's direction, she wonders whose legacy she is building―hers, or her husband's. As the monument rises, Emily's marriage, principles, and identity threaten to collapse. When the bridge finally stands finished, will she recognize the woman who built it? Based on the true story of the Brooklyn Bridge, The Engineer's Wife delivers an emotional portrait of a woman transformed by a project of unfathomable scale, which takes her into the bowels of the East River, suffragette riots, the halls of Manhattan's elite, and the heady, freewheeling temptations of P.T. Barnum. It's the story of a husband and wife determined to build something that lasts―even at the risk of losing each other. -

Come Follow the Band and Join the Circus! Friday And

COME FOLLOW THE BAND AND JOIN THE CIRCUS! Music by Cy Coleman Book by Mark Bramble Lyrics by Michael Stewart FRIDAY AND SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 15-16, 2013 AT 7:30pm AND SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 17, 2012 AT 2:00pm (Snow Dates: February 22-24, 2013) AUDITION DATES: OCTOBER 29, 30 AND NOVEMBER 1, 2012 "Barnum's the name. PT. Barnum. And I want to tell you that tonight you are going to see bar none -every eight, wonder and miracle that name stands for!" Here is the show that traces the career of America's greatest, showman from 1835 to the year he joined with James A. Bailey to form The Greatest Show On Earth. We’re going to be looking for all sorts of talents when we transform MNMS into the Greatest Show on Earth! Actors, Singers, Dancers, Tumblers, Jugglers, Acrobats and Gymnasts as well as an AMAZING crew are all needed! CAST INFORMATION Phineas Taylor Barnum - The Prince of Humbug Chairy Barnum - His wife Joice Heth oldest woman alive Tom Thumb - Smallest man in the world Julius Goldschmidt - Jenny Lind's manager Jenny Lind - Swedish soprano Blues Singer - female alto James A Bailey - Small circus owner 2 Ringmasters - Circus performers Chester Lyman - Joice Heth's manager Amos Scudder - Owner of the American Museum Sherwood Stratton - Tom Thumb's father Mrs Sherwood Stratton - Tom Thumb's mother Wilton - Barnum's assistant on the Jenny Lind tour Edgar Templeton - Political party boss Humbert Morrisey - Political party boss Plus a host of extras in a huge selection of parts Tumbers, jugglers, clowns aerialists, acrobats, gymnasts, bricklayers, passersby, museum patrons, strongmen, beefeaters, the "crowd" in general, the Bridgeport Pageant Choir and bands of every size, shape and description! SYNOPSIS To start we. -

Volume 25, Number 4 Winter 2013

ISSN 1059-1249 The Magic Lantern Gazette Volume 25, Number 4 Winter 2013 The Magic Lantern Society of the United States and Canada www.magiclanternsociety.org The Editor’s Page 2 Professor Cromwell in Buffalo “They are truly beautiful,” said a lady who was one of the large and delighted audience that left the Court Street theatre last eve- ning at the close of Prof. Cromwell’s tour through the varied scenery of different parts of Germany, and particularly the Rhine. The remark was directed in praise of the splendid series of views selected by Prof. Cromwell to illustrate his well-timed, semi- descriptive and quasi-humorous allusions to the many attractions which the scenery of the Rhine, the quaint architecture of such venerable German cities as Cologne, Coblenz, Mayence, and Frankfort...present to the traveler in that most interesting portion of the old world. A trip down the Rhine with Prof. Cromwell and his potent if not absolutely “magic” lantern, is indeed a most de- lightful journey…. “Court Street Theatre,” Buffalo Daily Courier, Oct. 21, 1884. This double-size issue of the Gazette is devoted entirely to Please check out the Magic Lantern Research Group at my own article on the lecturing career of Professor George www.zotero.org/groups/magic_lantern_research_group. Reed Cromwell. I have been doing research on Cromwell In the Group Library, you will find links to all back issues of for several years and previously presented some of this The Magic Lantern Gazette and Magic Lantern Bulletin work at one of our society conventions. Since then, I have online through the San Diego State University Library. -

"The Greatest Showman on Earth"

"THE GREATEST SHOWMAN ON EARTH" Written by Jenny Bicks Revisions by Jordan Roberts Bill Condon Jonathan Tropper Current Revisions by: M.A. April 20th, 2015 Draft The Greatest Showman On Earth 4/20/15 Draft 1. 1-3 OMITTED 1-3 A strummed BANJO begins... A BASS DRUM joins, beating time. 4 INT. CIRCUS TENT - NIGHT 4 Absolute darkness. Then, a single narrow spotlight goes on, revealing a RINGMASTER, with top hat, his back to us, alone. With his head bowed, the top hat casts his face in shadow. As the MUSIC picks up, he sings in a hushed, dramatic voice: RINGMASTER [BARNUM SINGS] [BARNUM SINGS] QUICK CUTS -- CLOSE UPS of the RINGMASTER, seen from behind, in fast-passing shots. The iconic top hat; the cane; red swallowtail coat; shiny black boots; sawdust... RINGMASTER (CONT’D) [BARNUM SINGS] [BARNUM SINGS] The Ringmaster (from behind) looks upward. Another spotlight goes on. Way up high in the darkness, a beautiful African- American aerialist, ANNE WHEELER, is spinning on a rope. RINGMASTER (CONT’D) [BARNUM SINGS] [BARNUM SINGS] The Ringmaster looks the other way -- a new spotlight hits a beautiful TIGHTROPE WALKER, way up high, seemingly walking on air through the vast darkness. RINGMASTER (CONT’D) [BARNUM SINGS] A cannon FIRES -- sending a HUMAN CANNONBALL flying through the darkness, spotlight following, til he lands in a netting. RINGMASTER (CONT’D) [BARNUM SINGS] The Ringmaster turns, into the light. It is P.T. BARNUM. Handsome. Confident. Exuberant. At the height of his powers. A showman’s smile; a scoundrel’s wink. BARNUM [BARNUM SINGS] [BARNUM SINGS] * (CONTINUED) The Greatest Showman On Earth 4/20/15 Draft 2.