Vol. 18 No. 2 Issncim

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scottish Birds 37:3 (2017)

Contents Scottish Birds 37:3 (2017) 194 President’s Foreword J. Main PAPERS 195 Potential occurrence of the Long-tailed Skua subspecies Stercorarius longicaudus pallescens in Scotland C.J. McInerny & R.Y. McGowan 202 Amendments to The Scottish List: species and subspecies The Scottish Birds Records Committee 205 The status of the Pink-footed Goose at Cameron Reservoir, Fife from 1991/92 to 2015/16: the importance of regular monitoring A.W. Brown 216 Montagu’s Harrier breeding in Scotland - some observations on the historical records from the 1950s in Perthshire R.L. McMillan SHORT NOTES 221 Scotland’s Bean Geese and the spring 2017 migration C. Mitchell, L. Griffin, A. MacIver & B. Minshull 224 Scoters in Fife N. Elkins OBITUARIES 226 Sandy Anderson (1927–2017) A. Duncan & M. Gorman 227 Lance Leonard Joseph Vick (1938–2017) I. Andrews, J. Ballantyne & K. Bowler ARTICLES, NEWS & VIEWS 229 The conservation impacts of intensifying grouse moor management P.S. Thompson & J.D. Wilson 236 NEWS AND NOTICES 241 Memories of the three St Kilda visitors in July 1956 D.I.M. Wallace, D.G. Andrew & D. Wilson 244 Where have all the Merlins gone? A lament for the Lammermuirs A.W. Barker, I.R. Poxton & A. Heavisides 251 Gannets at St Abb’s Head and Bass Rock J. Cleaver 254 BOOK REVIEWS 256 RINGERS' ROUNDUP Iain Livingstone 261 The identification of an interesting Richard’s Pipit on Fair Isle in June 2016 I.J. Andrews 266 ‘Canada Geese’ from Canada: do we see vagrants of wild birds in Scotland? J. Steele & J. -

Alles Wat Je Nog Niet Wist Over the Water of Life Fernand Dacquin Fernand Dacquin

ALLES WAT JE NOG NIET WIST OVER THE WATER OF LIFE FERNAND DACQUIN FERNAND DACQUIN ALLES WAT JE NOG NIET WIST OVER THE WATER OF LIFE WOORD VOORAF DOOR CHARLES MACLEAN Nog een whiskyboek! Ik schrijf al bijna veertig jaar over whisky. Ik heb zeventien boeken over het onderwerp gepubliceerd, er talloze artikelen over neergepend en tientallen boeken over whisky gelezen – misschien wel honderden. Je zou je heel goed kunnen afvragen: wat valt er nu nog meer of anders over dit onderwerp te vertellen? How many ways are there to skin a cat? Maar dit boek is anders. Fernand, de auteur, vertelde me: ‘Ik maak een boek over mensen, dingen en gebeurtenissen waar een whiskygeurtje aan hangt... Over de minder bekende kant van de whiskywereld, dus. Geen gepraat over het aantal liters, geen wetenschappelijke uitleg, tenzij nodig om het verhaal te begrijpen, en vooral gegarandeerd geen proefnotities. Maar wel 111 artikelen die je wellicht niet in een boek over whisky verwacht...’ 7 Ha! Waarom 111? 111 proof betekent hetzelfde als 63,5% Alcohol By Volume (ABV), en dat is een van de ‘magische getallen’ in whisky. Lang geleden werd ontdekt dat dit de optimale sterkte voor rijping is. New spirit wordt traditioneel tot dit niveau verdund, voordat het in het vat wordt gedaan. Deze subtiele, stille verwijzing naar whisky typeert Fernand. De onderwerpen die hij omarmt, zijn bovendien op zijn zachtst gezegd ongebruikelijk. Fernand en ik ontmoetten elkaar voor het eerst in 1998, op een whiskyfestival in Den Haag. Twee jaar geleden kwamen we elkaar opnieuw tegen, in Edinburgh en later Brussel, met Robrecht Willaert, hoofdredacteur van Travel Magazine en uitgever van de monumentale jaarlijkse A Journey: The Travel Industry Towards 2030. -

2019 Cruise Directory

Despite the modern fashion for large floating resorts, we b 7 nights 0 2019 CRUISE DIRECTORY Highlands and Islands of Scotland Orkney and Shetland Northern Ireland and The Isle of Man Cape Wrath Scrabster SCOTLAND Kinlochbervie Wick and IRELAND HANDA ISLAND Loch a’ FLANNAN Stornoway Chàirn Bhain ISLES LEWIS Lochinver SUMMER ISLES NORTH SHIANT ISLES ST KILDA Tarbert SEA Ullapool HARRIS Loch Ewe Loch Broom BERNERAY Trotternish Inverewe ATLANTIC NORTH Peninsula Inner Gairloch OCEAN UIST North INVERGORDON Minch Sound Lochmaddy Uig Shieldaig BENBECULA Dunvegan RAASAY INVERNESS SKYE Portree Loch Carron Loch Harport Kyle of Plockton SOUTH Lochalsh UIST Lochboisdale Loch Coruisk Little Minch Loch Hourn ERISKAY CANNA Armadale BARRA RUM Inverie Castlebay Sound of VATERSAY Sleat SCOTLAND PABBAY EIGG MINGULAY MUCK Fort William BARRA HEAD Sea of the Glenmore Loch Linnhe Hebrides Kilchoan Bay Salen CARNA Ballachulish COLL Sound Loch Sunart Tobermory Loch à Choire TIREE ULVA of Mull MULL ISLE OF ERISKA LUNGA Craignure Dunsta!nage STAFFA OBAN IONA KERRERA Firth of Lorn Craobh Haven Inveraray Ardfern Strachur Crarae Loch Goil COLONSAY Crinan Loch Loch Long Tayvallich Rhu LochStriven Fyne Holy Loch JURA GREENOCK Loch na Mile Tarbert Portavadie GLASGOW ISLAY Rothesay BUTE Largs GIGHA GREAT CUMBRAE Port Ellen Lochranza LITTLE CUMBRAE Brodick HOLY Troon ISLE ARRAN Campbeltown Firth of Clyde RATHLIN ISLAND SANDA ISLAND AILSA Ballycastle CRAIG North Channel NORTHERN Larne IRELAND Bangor ENGLAND BELFAST Strangford Lough IRISH SEA ISLE OF MAN EIRE Peel Douglas ORKNEY and Muckle Flugga UNST SHETLAND Baltasound YELL Burravoe Lunna Voe WHALSAY SHETLAND Lerwick Scalloway BRESSAY Grutness FAIR ISLE ATLANTIC OCEAN WESTRAY SANDAY STRONSAY ORKNEY Kirkwall Stromness Scapa Flow HOY Lyness SOUTH RONALDSAY NORTH SEA Pentland Firth STROMA Scrabster Caithness Wick Welcome to the 2019 Hebridean Princess Cruise Directory Unlike most cruise companies, Hebridean operates just one very small and special ship – Hebridean Princess. -

2020 Cruise Directory Directory 2020 Cruise 2020 Cruise Directory M 18 C B Y 80 −−−−−−−−−−−−−−− 17 −−−−−−−−−−−−−−−

2020 MAIN Cover Artwork.qxp_Layout 1 07/03/2019 16:16 Page 1 2020 Hebridean Princess Cruise Calendar SPRING page CONTENTS March 2nd A Taste of the Lower Clyde 4 nights 22 European River Cruises on board MS Royal Crown 6th Firth of Clyde Explorer 4 nights 24 10th Historic Houses and Castles of the Clyde 7 nights 26 The Hebridean difference 3 Private charters 17 17th Inlets and Islands of Argyll 7 nights 28 24th Highland and Island Discovery 7 nights 30 Genuinely fully-inclusive cruising 4-5 Belmond Royal Scotsman 17 31st Flavours of the Hebrides 7 nights 32 Discovering more with Scottish islands A-Z 18-21 Hebridean’s exceptional crew 6-7 April 7th Easter Explorer 7 nights 34 Cruise itineraries 22-97 Life on board 8-9 14th Springtime Surprise 7 nights 36 Cabins 98-107 21st Idyllic Outer Isles 7 nights 38 Dining and cuisine 10-11 28th Footloose through the Inner Sound 7 nights 40 Smooth start to your cruise 108-109 2020 Cruise DireCTOrY Going ashore 12-13 On board A-Z 111 May 5th Glorious Gardens of the West Coast 7 nights 42 Themed cruises 14 12th Western Isles Panorama 7 nights 44 Highlands and islands of scotland What you need to know 112 Enriching guest speakers 15 19th St Kilda and the Outer Isles 7 nights 46 Orkney, Northern ireland, isle of Man and Norway Cabin facilities 113 26th Western Isles Wildlife 7 nights 48 Knowledgeable guides 15 Deck plans 114 SuMMER Partnerships 16 June 2nd St Kilda & Scotland’s Remote Archipelagos 7 nights 50 9th Heart of the Hebrides 7 nights 52 16th Footloose to the Outer Isles 7 nights 54 HEBRIDEAN -

Where to Go: Puffin Colonies in Ireland Over 15,000 Puffin Pairs Were Recorded in Ireland at the Time of the Last Census

Where to go: puffin colonies in Ireland Over 15,000 puffin pairs were recorded in Ireland at the time of the last census. We are interested in receiving your photos from ANY colony and the grid references for known puffin locations are given in the table. The largest and most accessible colonies here are Great Skellig and Great Saltee. Start Number Site Access for Pufferazzi Further information Grid of pairs Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Great Skellig V247607 4,000 worldheritageireland.ie/skellig-michael check local access arrangements Puffin Island - Kerry V336674 3,000 Access more difficult Boat trips available but landing not possible 1,522 Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Great Saltee X950970 salteeislands.info check local access arrangements Mayo Islands l550938 1,500 Access more difficult Illanmaster F930427 1,355 Access more difficult Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Cliffs of Moher, SPA R034913 1,075 check local access arrangements Stags of Broadhaven F840480 1,000 Access more difficult Tory Island and Bloody B878455 894 Access more difficult Foreland Kid Island F785435 370 Access more difficult Little Saltee - Wexford X968994 300 Access more difficult Inishvickillane V208917 170 Access more difficult Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Horn Head C005413 150 check local access arrangements Lambay Island O316514 87 Access more difficult Pig Island F880437 85 Access more difficult Inishturk Island L594748 80 Access more difficult Clare Island L652856 25 Access more difficult Beldog Harbour to Kid F785435 21 Access more difficult Island Mayo: North West F483156 7 Access more difficult Islands Ireland’s Eye O285414 4 Access more difficult Howth Head O299389 2 Access more difficult Wicklow Head T344925 1 Access more difficult Where to go: puffin colonies in Inner Hebrides Over 2,000 puffin pairs were recorded in the Inner Hebrides at the time of the last census. -

Shetland Islands, United Kingdom

Journal of Global Change Data & Discovery. 2018, 2(2): 224-227 © 2018 GCdataPR DOI:10.3974/geodp.2018.02.18 Global Change Research Data Publishing & Repository www.geodoi.ac.cn Global Change Data Encyclopedia Shetland Islands, United Kingdom Liu, C.* Shi, R. X. Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China Keywords: Shetland Islands; Scotland; United Kingdom; Atlantic Ocean; data encyclopedia The Shetland Islands of Scotland is located from 59°30′24″N to 60°51′39″N, from 0°43′25″W to 2°7′3″W, between the North Sea and the Atlantic Ocean (Figure 1, Figure 2). Shetland Islands extend 157 km from the northernmost Out Stack Isle to the southernmost Fair Isle. The Islands are 300 km to the west coast of Norway in its east, 291 km to the Faroe Islands in its northwest and 43 km to the North Ronaldsay in its southwest[1–2]. The Main- land is the main island in the Shetland Islands, and 168 km to the Scotland in its south. The Shetland Islands are consisted of 1,018 islands and islets, in which the area of each island or islet is more than 6 m2. The total area of the Shetland Islands is 1,491.33 km2, and the coastline is 2,060.13 km long[1]. There are only 23 islands with each area more than 1 km2 in the Shetland Islands (Table 1), account- ing for 2% of the total number of islands and 98.67% of the total area of the islands. -

Layout 1 Copy

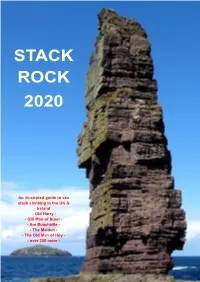

STACK ROCK 2020 An illustrated guide to sea stack climbing in the UK & Ireland - Old Harry - - Old Man of Stoer - - Am Buachaille - - The Maiden - - The Old Man of Hoy - - over 200 more - Edition I - version 1 - 13th March 1994. Web Edition - version 1 - December 1996. Web Edition - version 2 - January 1998. Edition 2 - version 3 - January 2002. Edition 3 - version 1 - May 2019. Edition 4 - version 1 - January 2020. Compiler Chris Mellor, 4 Barnfield Avenue, Shirley, Croydon, Surrey, CR0 8SE. Tel: 0208 662 1176 – E-mail: [email protected]. Send in amendments, corrections and queries by e-mail. ISBN - 1-899098-05-4 Acknowledgements Denis Crampton for enduring several discussions in which the concept of this book was developed. Also Duncan Hornby for information on Dorset’s Old Harry stacks and Mick Fowler for much help with some of his southern and northern stack attacks. Mike Vetterlein contributed indirectly as have Rick Cummins of Rock Addiction, Rab Anderson and Bruce Kerr. Andy Long from Lerwick, Shetland. has contributed directly with a lot of the hard information about Shetland. Thanks are also due to Margaret of the Alpine Club library for assistance in looking up old journals. In late 1996 Ben Linton, Ed Lynch-Bell and Ian Brodrick undertook the mammoth scanning and OCR exercise needed to transfer the paper text back into computer form after the original electronic version was lost in a disk crash. This was done in order to create a world-wide web version of the guide. Mike Caine of the Manx Fell and Rock Club then helped with route information from his Manx climbing web site. -

Boomerang's 2008 Log Norway the Shetland Islands St Kilda

Boomerang’s 2008 Log Norway The Shetland Islands St Kilda 2 April & May South Queensferry to Bergen Hardanger Fjord, Bomlo & Stord Selbjornsfjord to Lerwick Circumnavigation of The Shetland Islands Fair Isle The Orkney Islands Kirkwall to the River Tay Return to South Queensferry 2 3 The Preparations When my diagnosis of MND was confirmed in July 2007 I decided it was time to retire and start off-shore sailing. My first idea was to join the 2008 ARC and for this I needed to find a sailing companion, somebody either unemployed or able to throw off the shackles of labour for a few months. I posted adverts in local yacht clubs and subscribed to the crew-seekers website but without luck until my neighbour at Port Edgar Marina put me in touch with Mike Bowley. We first met in September and I discovered he was an experienced yachtsman, out of work, and although not available to sail south to the Canaries that October, we agreed to cross to Norway the following April. It was a long term ambition of mine to sail to Bergen and somehow I preferred this to sitting in the Caribbean sun. Boomerang is a 35ft Hustler with fin keel and skeg, built in 1971. When I bought her in 2004 I kept her on west coast to sail and make her seaworthy. This meant replacing the sea-cocks and hoses, improving the cockpit drainage, up-grading the primary fuel system and replacing switch panels and most of the wiring. To satisfy the insurers, my gas stove supply also needed modernised but as this would also involve fitting sensors and alarms, I ditched the gas stove overboard and bought a spirit Origa twin burner top stove instead. -

The Invertebrate Fauna of Dune and Machair Sites In

INSTITUTE OF TERRESTRIAL ECOLOGY (NATURAL ENVIRONMENT RESEARCH COUNCIL) REPORT TO THE NATURE CONSERVANCY COUNCIL ON THE INVERTEBRATE FAUNA OF DUNE AND MACHAIR SITES IN SCOTLAND Vol I Introduction, Methods and Analysis of Data (63 maps, 21 figures, 15 tables, 10 appendices) NCC/NE RC Contract No. F3/03/62 ITE Project No. 469 Monks Wood Experimental Station Abbots Ripton Huntingdon Cambs September 1979 This report is an official document prepared under contract between the Nature Conservancy Council and the Natural Environment Research Council. It should not be quoted without permission from both the Institute of Terrestrial Ecology and the Nature Conservancy Council. (i) Contents CAPTIONS FOR MAPS, TABLES, FIGURES AND ArPENDICES 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 OBJECTIVES 2 3 METHODOLOGY 2 3.1 Invertebrate groups studied 3 3.2 Description of traps, siting and operating efficiency 4 3.3 Trapping period and number of collections 6 4 THE STATE OF KNOWL:DGE OF THE SCOTTISH SAND DUNE FAUNA AT THE BEGINNING OF THE SURVEY 7 5 SYNOPSIS OF WEATHER CONDITIONS DURING THE SAMPLING PERIODS 9 5.1 Outer Hebrides (1976) 9 5.2 North Coast (1976) 9 5.3 Moray Firth (1977) 10 5.4 East Coast (1976) 10 6. THE FAUNA AND ITS RANGE OF VARIATION 11 6.1 Introduction and methods of analysis 11 6.2 Ordinations of species/abundance data 11 G. Lepidoptera 12 6.4 Coleoptera:Carabidae 13 6.5 Coleoptera:Hydrophilidae to Scolytidae 14 6.6 Araneae 15 7 THE INDICATOR SPECIES ANALYSIS 17 7.1 Introduction 17 7.2 Lepidoptera 18 7.3 Coleoptera:Carabidae 19 7.4 Coleoptera:Hydrophilidae to Scolytidae -

Hiking Scotland's

Hiking Scotland’s North Highlands & Isle of Lewis July 20-30, 2021 (11 days | 15 guests) with archaeologist Mary MacLeod Rivett Archaeology-focused tours for the curious to the connoisseur. Clachtoll Broch Handa Island Arnol Dun Carloway (5.5|645) (6|890) BORVE Great Bernera & Traigh Uige 3 Caithness Dunbeath(4.5|425) (6|870) Stornoway (5|~) 3 3 BRORA Glasgow Isle of Lewis Callanish Lairg Standing Stones Ullapool (4.5|~) (4.5|885) Ardvreck LOCHINVER Castle Inverness Little Assynt # Overnight stays Itinerary stops Scottish Flights Hikes (miles|feet) Highlands Ferry Archaeological Institute of America Lecturer & Host Dr. Mary MacLeod oin archaeologist Mary MacLeod Rivett and a small group of like- Rivett was born in minded travelers on this 11-day tour of Scotland’s remote north London, England, to J Highlands and the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides. Mostly we a Scottish-Canadian family. Her father’s will explore off the well-beaten Highland tourist trail, and along the way family was from we will be treated to an abundance of archaeological and historical sites, Scotland’s Outer striking scenery – including high cliffs, sea lochs, sandy and rocky bays, Hebrides, and she mountains, and glens – and, of course, excellent hiking. spent a lot of time in the Hebrides as a child. Mary earned her Scotland’s long and varied history stretches back many thousands of B.A. from the University of Cambridge, years, and archaeological remains ranging from Neolithic cairns and and her M.A. from the University of stone circles to Iron Age brochs (ancient dry stone buildings unique to York. -

ANTARES CHARTS 2020 Full List in Chart Number Order

ANTARES CHARTS 2020 Full list in chart number order. Key at end of list Chart name Number Status Sanda Roads, Sanda Island, edition 1 5517 Y U Pladda Anchorage, South Arran, edition 1 5525 Y N Sound of Pladda, South Arran, edition 1 5526 Y U Kingscross Anchorage, Lamlash Bay, Isle of Arran, editon 1 5530 Y N Holy Island Anchorage, Lamlash Bay, Isle of Arran, edition 1 5531 Y N Lamlash Anchorage, Lamlash Bay, Isle of Arran, edition 1 5532 Y N Port Righ, Carradale, Kilbrannan Sound, edition 1 5535 Y U Brodick Old Quay Anchorage, Isle of Arran,edition 1 5535 YA N Lagavulin Bay, Islay, edition 2 5537 A U Loch Laphroaig, Islay, edition 2 5537 B C Chapel Bay, Texa, edition 1 5537 C U Caolas an Eilein, Texa, edition 1 5537 D U Ardbeg & Loch an t-Sailein, edition 3 5538 A U Cara Reef Bay, Gigha, edition 2 5538 B C Loch an Chnuic, edition 3 5539 A C Port an Sgiathain, Gigha, edition 2 5539 B C Caolas Gigalum, Gigha, edition 1 5539 C N North Gigalum Anchorge, Gigha, edition 1 5539 D N Ardmore Islands, East Islay, edition 5 5540 A C Craro Bay, Gigha, edition 2 5540 B C Port Gallochoille, Gigha, edition 2 5540 C C Ardminish Bay, Gigha, edition 3 5540 D M Glas Uig, East Coast of Islay, edition 3 5541 A C Port Mor, East Islay, edition 2 5541 B C Aros Bay, East Islay, edition 2 5541 C C Ardminish Point Passage, Gigha, edition 2 5541 D C Druimyeon Bay, Gigha, edition 1 5541 E N West Tarbert Bay, South Anchorage, Gigha, edition 2 5542 A C East Tarbert Bay, Gigha, edition 2 5542 B C Loch Ranza, Isle of Arran, edition 2 5542 Y M Bagh Rubha Ruaidh, West Tarbert -

Scottish Sea Kayaking Sea Scottish

Scottish Sea Kayaking At last, here it is… Scotland’s first guidebook for sea kayakers wishing to explore its amazing coastline and magical islands. It brings together a selection of fifty great sea voyages around the mainland of Scotland, Doug Cooper & George Reid from the Mull of Galloway in the SW to St Abb’s Head on the east coast, as well as voyages in the Western Isles, ranging from day trips to three day journeys. Illustrated with superb colour photographs and useful maps throughout, it is a practical guide to help you select and plan trips. It will provide inspiration for future voyages and a souvenir of journeys undertaken. As well as providing essential information on where to start and finish, distances, times and tidal information, the book does much to stimulate and inform our interest in the environment we are passing through. It is full of facts and anecdotes about local history, geology, scenery, seabirds and sea mammals. A fascinating read and an inspirational book. Scottish Sea Kayaking Scottish Sea Kayaking fifty great sea kayak voyages fifty great sea kayak voyages Doug Cooper & George Reid Also available from 35 36 38 39 33 37 Pesda Press 40 27 26 Sea Kayak Navigation 41 The Seamanship Pocketbook Stornoway 32 25 Welsh Sea Kayaking 24 South West Sea Kayaking 22 34 21 The Northern Isles 31 23 Oileáin - A Guide to the Irish Islands 18 43 30 17 44 Kayak Surfing 42 16 Kayak Rolling 29 19 Scottish White Water 15 Inverness 45 English White Water 14 20 Canoe and Kayak Handbook White Water Safety and Rescue 13 ..