WEBGUI: a Web Browser Based Graphical User Interface for Scientific Software Users’ Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Next Generation Web Scanning Presentation

Next generation web scanning New Zealand: A case study First presented at KIWICON III 2009 By Andrew Horton aka urbanadventurer NZ Web Recon Goal: To scan all of New Zealand's web-space to see what's there. Requirements: – Targets – Scanning – Analysis Sounds easy, right? urbanadventurer (Andrew Horton) www.morningstarsecurity.com Targets urbanadventurer (Andrew Horton) www.morningstarsecurity.com Targets What does 'NZ web-space' mean? It could mean: •Geographically within NZ regardless of the TLD •The .nz TLD hosted anywhere •All of the above For this scan it means, IPs geographically within NZ urbanadventurer (Andrew Horton) www.morningstarsecurity.com Finding Targets We need creative methods to find targets urbanadventurer (Andrew Horton) www.morningstarsecurity.com DNS Zone Transfer urbanadventurer (Andrew Horton) www.morningstarsecurity.com Find IP addresses on IRC and by resolving lots of NZ websites 58.*.*.* 60.*.*.* 65.*.*.* 91.*.*.* 110.*.*.* 111.*.*.* 113.*.*.* 114.*.*.* 115.*.*.* 116.*.*.* 117.*.*.* 118.*.*.* 119.*.*.* 120.*.*.* 121.*.*.* 122.*.*.* 123.*.*.* 124.*.*.* 125.*.*.* 130.*.*.* 131.*.*.* 132.*.*.* 138.*.*.* 139.*.*.* 143.*.*.* 144.*.*.* 146.*.*.* 150.*.*.* 153.*.*.* 156.*.*.* 161.*.*.* 162.*.*.* 163.*.*.* 165.*.*.* 166.*.*.* 167.*.*.* 192.*.*.* 198.*.*.* 202.*.*.* 203.*.*.* 210.*.*.* 218.*.*.* 219.*.*.* 222.*.*.* 729,580,500 IPs. More than we want to try. urbanadventurer (Andrew Horton) www.morningstarsecurity.com IP address blocks in the IANA IPv4 Address Space Registry Prefix Designation Date Whois Status [1] ----- -

Dialogic® Powermedia™ XMS JSR 309 Connector Software Release 5.2 Installation and Configuration Guide with Oracle Communications Converged Application Server 5.1

Dialogic® PowerMedia™ XMS JSR 309 Connector Software Release 5.2 Installation and Configuration Guide with Oracle Communications Converged Application Server 5.1 July 2016 Rev 2.0 www.dialogic.com Copyright and Legal Notice Copyright © 2016 Dialogic Corporation. All Rights Reserved. You may not reproduce this document in whole or in part without permission in writing from Dialogic Corporation at the address provided below. All contents of this document are furnished for informational use only and are subject to change without notice and do not represent a commitment on the part of Dialogic Corporation and its affiliates or subsidiaries ("Dialogic"). Reasonable effort is made to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in the document. However, Dialogic does not warrant the accuracy of this information and cannot accept responsibility for errors, inaccuracies or omissions that may be contained in this document. INFORMATION IN THIS DOCUMENT IS PROVIDED IN CONNECTION WITH DIALOGIC® PRODUCTS. NO LICENSE, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, BY ESTOPPEL OR OTHERWISE, TO ANY INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS IS GRANTED BY THIS DOCUMENT. EXCEPT AS PROVIDED IN A SIGNED AGREEMENT BETWEEN YOU AND DIALOGIC, DIALOGIC ASSUMES NO LIABILITY WHATSOEVER, AND DIALOGIC DISCLAIMS ANY EXPRESS OR IMPLIED WARRANTY, RELATING TO SALE AND/OR USE OF DIALOGIC PRODUCTS INCLUDING LIABILITY OR WARRANTIES RELATING TO FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE, MERCHANTABILITY, OR INFRINGEMENT OF ANY INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHT OF A THIRD PARTY. Dialogic products are not intended for use in certain safety-affecting situations. Please see http://www.dialogic.com/company/terms-of-use.aspx for more details. Due to differing national regulations and approval requirements, certain Dialogic products may be suitable for use only in specific countries, and thus may not function properly in other countries. -

Automated Coevolution of Source Code and Software Architecture Models the Karlsruhe Series on Software Design and Quality Volume 23

The Karlsruhe Series on Software Design and Quality 23 Automated Coevolution of Source Code and Software Architecture Models Michael Langhammer Automated Coevolution of Source Code Automated Coevolution of Source Models Architecture and Software Michael Langhammer Michael Langhammer Automated Coevolution of Source Code and Software Architecture Models The Karlsruhe Series on Software Design and Quality Volume 23 Chair Software Design and Quality Faculty of Computer Science Karlsruhe Institute of Technology and Software Engineering Division Research Center for Information Technology (FZI), Karlsruhe Editor: Prof. Dr. Ralf Reussner Automated Coevolution of Source Code and Software Architecture Models by Michael Langhammer Dissertation, Karlsruher Institut für Technologie KIT-Fakultät für Informatik Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 10. Februar 2017 Erster Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Ralf H. Reussner Zweiter Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Colin Atkinson (Universität Mannheim) Impressum Karlsruher Institut für Technologie (KIT) KIT Scientific Publishing Straße am Forum 2 D-76131 Karlsruhe KIT Scientific Publishing is a registered trademark of Karlsruhe Institute of Technology. Reprint using the book cover is not allowed. www.ksp.kit.edu This document – excluding the cover, pictures and graphs – is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License (CC BY-SA 4.0): https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en The cover page is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-ND 4.0): https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0/deed.en Print on Demand 2019 – Gedruckt auf FSC-zertifiziertem Papier ISSN 1867-0067 ISBN 978-3-7315-0783-3 DOI: 10.5445/KSP/1000081447 Abstract To develop complex software systems, source code and other artefacts, such as architectural models and behaviour descriptions, are used. -

840 Presentation

UNTANGLING A TANGLED WEB: a case study in choosing and implementing a CMS T. L. Huttenlock, J. W. Beaird, R. W. Fordham Library Hi Tech 24(1): 61-68 Heather Braum, LI840, 10/07 1 Case Study Information Location: Buswell Memorial Library, Wheaton College (IL) Project: Process of choosing content management system (CMS) Study Type: Reflective case study Findings: Overview of the entire process of choosing the library’s CMS Heather Braum, LI840, 10/07 2 “Old” Days First years of web design: Dreamweaver, FrontPage or other HTML editor Had to know complicated code Software installed on each user’s computer Difficult to use, even after training Expensive commercial licensing Many website updates had to go through multiple people...complicated process in the “old” way Heather Braum, LI840, 10/07 3 What is a CMS? A content management system (CMS) is a software (typically web-based) application that manages content, such as computer files, audio, video, images, and web content, and allows a large number of users to make changes. (Wikipedia1) A web CMS is a web application used for creating and managing a large, dynamic collection of web material. It allows users with little or no training in programming/code to make changes to an existing website. It is essentially a website maintenance tool for non-technical administrators. (Wikipedia2) 1. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Content_management_systems 2. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Web_content_management_system Heather Braum, LI840, 10/07 4 How CMS works Many CMS are open source Installed on a server (typically with PHP and MySQL installed -- programming software) The setup of a CMS does take some technical skill But the end-user side is easy Today, many people use a CMS without ever realizing it Heather Braum, LI840, 10/07 5 Examples of CMS Wordpress--KLOW1 CMS (http://www.wordpress.org/) MoveableType (http://www.moveabletype.org/) MediaWiki--Wikipedia2 CMS (http://www.mediawiki.org) TikiWiki (http://www.tikiwiki.org/) Drupal (http://www.drupal.org/) Web GUI (http://www.plainback.com/webgui) 1. -

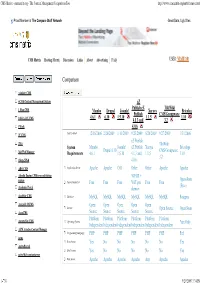

CMS Matrix - Cmsmatrix.Org - the Content Management Comparison Tool

CMS Matrix - cmsmatrix.org - The Content Management Comparison Tool http://www.cmsmatrix.org/matrix/cms-matrix Proud Member of The Compare Stuff Network Great Data, Ugly Sites CMS Matrix Hosting Matrix Discussion Links About Advertising FAQ USER: VISITOR Compare Search Return to Matrix Comparison <sitekit> CMS +CMS Content Management System eZ Publish eZ TikiWiki 1 Man CMS Mambo Drupal Joomla! Xaraya Bricolage Publish CMS/Groupware 4.6.1 6.10 1.5.10 1.1.5 1.10 1024 AJAX CMS 4.1.3 and 3.2 1Work 4.0.6 2F CMS Last Updated 12/16/2006 2/26/2009 1/11/2009 9/23/2009 8/20/2009 9/27/2009 1/31/2006 eZ Publish 2flex TikiWiki System Mambo Joomla! eZ Publish Xaraya Bricolage Drupal 6.10 CMS/Groupware 360 Web Manager Requirements 4.6.1 1.5.10 4.1.3 and 1.1.5 1.10 3.2 4Steps2Web 4.0.6 ABO.CMS Application Server Apache Apache CGI Other Other Apache Apache Absolut Engine CMS/news publishing 30EUR + system Open-Source Approximate Cost Free Free Free VAT per Free Free (Free) Academic Portal domain AccelSite CMS Database MySQL MySQL MySQL MySQL MySQL MySQL Postgres Accessify WCMS Open Open Open Open Open License Open Source Open Source AccuCMS Source Source Source Source Source Platform Platform Platform Platform Platform Platform Accura Site CMS Operating System *nix Only Independent Independent Independent Independent Independent Independent ACM Ariadne Content Manager Programming Language PHP PHP PHP PHP PHP PHP Perl acms Root Access Yes No No No No No Yes ActivePortail Shell Access Yes No No No No No Yes activeWeb contentserver Web Server Apache Apache -

Clare Swan 650.678.0067 (Cell) • [email protected] •

Clare Swan 650.678.0067 (cell) • [email protected] • http://people.stanford.edu/crswan PROFESSIONAL PROFILE Creative Web Developer with excellent communication and interpersonal skills. Expertise in dynamic web development, project management, and database administration used to develop and deploy new and custom systems. Proven track record of supporting all aspects of web and database development. EMPLOYMENT HISTORY Stanford University, Stanford, CA (2007 – Current) Web Developer Precourt Energy Efficiency Center (peec.stanford.edu) Global Climate and Energy Project (gcep.stanford.edu) Magic Lab (magiclab.stanford.edu) Precourt Institute for Energy (energy.stanford.edu) TomKat Center for Sustainable Energy (tomkat.stanford.edu) • Complete website support including development, design, and ongoing maintenance, using Drupal (including Stanford Web Services templates, JSA, sites), Wordpress, and Dreamweaver to deploy all aspects on a variety of websites. Monitor web metrics via Google Analytics to track website usage and usability in regards to website improvements for the user and effectiveness of marketing emails. Graphic creation and manipulation using various imaging software (Photoshop, Illustrator). Create forms and surveys via Qualtrics, SurveyMonkey, and Stanford’s Web Form Service to analyze event and website effectiveness for future improvements. Implement secure access to parts of the website using Stanford’s security technology. Use current web standards and technologies to comply with Stanford/departmental web branding, policy and guidelines. • Project Management overseeing design and development of new & existing websites. Partner with Stanford Web Services to implement new Drupal websites. Schedule & conduct meetings with management, staff and internal/external vendors. Utilize Stanford Self-help Web Design Resources including: Stanford modern templates, AFS Group Space, Workgroups/Tools, Vanity URL’s/Virtual hosts, Web Form Service, CGI service and Web Accessibility Standards & Guidelines. -

Automated Testing with WWW::Mechanize Copyright 2004, Andy Lester Automated Testing Philosophy Why Test?

Automated Testing with WWW::Mechanize Copyright 2004, Andy Lester Automated testing philosophy Why test? Humans make mistakes Bugs cost time & money Bugs are demoralizing Testing shows that your code works At least in the cases that you're testing Why automated testing? Humans hate testing. Computers don't. Instantly verify changes haven't broken code Regularly verify all code More tests don’t make the computer grumble Automated testing philosophy You are human Testing is an investment Test for now Test for the future Test constantly You are human You're good, but not that good Your coworkers are human, too Machines work, humans think Machines are good at repetitive tasks. A cron job will never blow off its tasks because they're boring. Test for the future Testing will detect breakage in the future (at least if you actually run the tests) 99.99% of the time, the test runs fine This is not a waste Proves that your code still works as you wrote it. Eliminate future stress and frustration! How Perl handles testing • Test::Harness runs your .t files • The .t files run tests, and reports results to standard output. • T::H analyzes the output and gives the thumbs up or thumbs down. What's a .t file? A .t file is just a Perl file Test::Harness looks for the .t extension by convention Each one runs one or more tests Results of each test are reported to standard output for parsing The test results format Simple text-based output One line per test says the test passes or fails. -

Society of American Archivists Council Meeting August 25, 2008 San Francisco, California

Agenda Item II.O. Society of American Archivists Council Meeting August 25, 2008 San Francisco, California Report: Website Working Group (Prepared by Brian Doyle, Chair) WORKING GROUP MEMBERS Brian Doyle, Chair Gregory Colati Christine Di Bella Chatham Ewing Jeanne Kramer-Smyth Mark Matienzo Aprille McKay Christopher Prom Seth Shaw Bruce Ambacher, Council Liaison BACKGROUND For several years, there has been a keen and growing interest among SAA’s members in the deployment of a robust content management system (CMS) featuring state-of-the-art Web 2.0 applications—wikis, blogs, RSS feeds, etc. While these types of programs are often associated with social networking, a comprehensive CMS would also redress a number of important organizational challenges that SAA faces: • How can SAA’s component groups (e.g., boards, committees, task forces, etc.) collaborate more effectively in an online environment? • How can official documents (e.g., minutes, reports, newsletters, etc.) be more easily published to the Web by SAA’s component groups, described and accessed via appropriate metadata, and scheduled for retention? • How can SAA enhance its online publishing capabilities and ensure that the necessary tools are available for authorized subject experts to edit and update such official electronic publications as Richard Pearce-Moses’ Glossary of Archival and Records Management Terminology , DACS Online, and the EAD Help Pages, as well as such important resources as an SAA standards portal or the Technology Best Practices Task Force working document? Report: Website Working Group Page 1 of 17 0808-1-WebWG-IIO SAA’s existing Web technology does not adequately fulfill these needs. -

Muodollisia Ohjeita

Choosing a Platform as a Service for Software as a Service Provider University of Oulu Department of Information Processing Science Master’s Thesis Antti Kreivi 06.03.2014 2 Abstract Cloud computing is still very sparsely researched, especially concerning platform as a service(PaaS) deployment model. PaaS model is still a very new in cloud computing and often confused with more familiar IaaS and SaaS models. First the basic concepts of cloud computing such as essential characters, deployment models and service models are presented and everything in cloud computing lean on these main concepts. The main objectives in this thesis are, to find out why PaaS is better alternative than building an own platform over a selected infrastructure, and to justify, why the selected PaaS is the most suitable for a cloud software project. PaaS has many advantages and concerns that must be sort out before a decision of deploying one can be made. With PaaS, developers do not need to know much about underlying cloud infrastructure and the infrastructure services are usually completely hidden, instead they can focus more on the development. PaaS platforms bring also a lot of cost reductions from reduced hardware needs, staff and more predictable expenditure. The biggest challenges in PaaS are the security and privacy concerns, and possible vendor lock-in risks. The four PaaS alternatives which are measured are Amazon Web Services with Beanstalks, Google App Engine, Heroku and Cloud Foundry. These are selected from number of alternatives together with the contractor. These four were among the most well-known PaaS providers and they were the most suitable with the contractor's project and with the criteria. -

TERMO DE REFERÊNCIA Aquisição De Soluções Em Segurança Da Informação

GOVERNO DO DISTRITO FEDERAL AGÊNCIA DE DESENVOLVIMENTO DO DISTRITO FEDERAL - TERRACAP Divisão de Suporte Termo de Referência SEI-GDF - TERRACAP/PRESI/CODIN/DISUP TERMO DE REFERÊNCIA Aquisição de soluções em segurança da informação 1. OBJETO DA CONTRATAÇÃO Registro de preços para eventual contratação de empresa(s) especializada(s) no fornecimento dos seguintes produtos e serviços: Lote Bem/Serviço 1000 (hum mil) licenças de solução de proteção para endpoints e anspam, com garana de funcionamento pelo período de 24 (vinte e quatro) meses, após o período inicial de garana de 12 (doze meses), totalizando 36 (trinta e seis) meses 1 de suporte ininterrupto, incluídos todos os sowares e suas licenças de uso, gerenciamento centralizado, contemplando os serviços de implantação, configuração, garana de atualização connua e repasse de conhecimento (capacitação) de toda a solução. Aquisição de 1 cluster de firewall baseado em appliance (mínimo de dois disposivos) e 1 cluster em servidores intel (2 licenças – atualmente instalado em servidor Dell R720), incluindo soware de gerência, instalação, configuração, 2 operação assisda de 200 horas, atualização de novas versões, suporte técnico, capacitação e garana por 24 (vinte e quatro) meses após a garana inicial de 12 (doze) meses, totalizando 36 (trinta e seis) meses de suporte ininterrupto. Os requisitos técnicos completos estão descritos no ANEXO I deste termo de referência. 2. JUSTIFICAVA DA CONTRATAÇÃO 2.1. É inquesonável a relevância dos serviços de TI para o bom desempenho das avidades da TERRACAP. A eventual indisponibilidade desses serviços causa impactos severos aos trabalhos, sejam eles finalíscos ou de apoio, podendo até mesmo impedir ou dificultar as ações instucionais. -

Setting up Intermediary Services

IBM WebSphere Application Server Network Deployment for Distributed Platforms, Version 8.0 Setting up intermediary services Note Before using this information, be sure to read the general information under “Notices” on page 365. Compilation date: July 15, 2011 © Copyright IBM Corporation 2011. US Government Users Restricted Rights – Use, duplication or disclosure restricted by GSA ADP Schedule Contract with IBM Corp. Contents How to send your comments . vii Changes to serve you more quickly . ix Chapter 1. How do I...Setting up intermediary services . 1 Chapter 2. Implementing a web server plug-in . 3 Setting up a local web server . 5 Setting up a remote web server . .8 Installing IBM HTTP Server . .11 Editing web server configuration files . 12 Configuring Apache HTTP Server V2.0 . 13 Configuring Apache HTTP Server V2.2 . 16 Configuring Lotus Domino . 18 Configuring IBM HTTP Server powered by Apache 2.x . .21 Configuring IBM HTTP Server Version 6.x . 23 Configuring IBM HTTP Server Version 7.0 . 25 Configuring IBM HTTP Server Version 8.0 . 27 Configuring Microsoft Internet Information Services (IIS) . 29 Configuring the Sun Java System Web Server . .34 Creating web server templates . 35 Allowing web servers to access the administrative console . 36 Administering web servers from the administrative console . 38 Web server definition . 38 Web server configuration . .39 Web server collection . .43 Editing the web server type . .50 Web server plug-ins . 51 Selecting a front end for your WebSphere Application Server topology . .52 Web server plug-in connections . 55 Web server plug-in remote user information processing . 56 Private headers . 57 Gskit install images files . -

The Webgui Runtime Environment

The WebGUI Runtime Environment Roy Johnson Plain Black Corporation What is the WRE? • All the supporting software required to host WebGUI • Apache 2 / Mod_Perl 2 • MySQL 5 • Supporting Perl Modules • AWStats • Utilities for administering WebGUI Sites Benefits • Easier Installation • Download • Unzip • Run Setup • Done! Benefits • Standardization • Site Database Names • Filenames • Paths • Templated Configuration Files Benefits • Performance • Pre-tuned Configuration • Reverse Proxy by Default • Mod_deflate Benefits • Easier Administration • 30 Seconds to create a site • Automated Log Rotation / Backups / WebGUI Upgrades • Service Monitoring and Automated Recovery with Notifications • Demo ready (your own demo.plainblack.com) Binary Distributions Available • Red Hat Enterprise Linux / Fedora Core 3/4 • Debian • Mac OS X (PPC and i686) • SuSe 9.3 • You can compile from source (and contribute it!) Installing with a WRE Binary • Download for your OS and Unzip • Create a data folder on / and copy wre folder to it • Add a mysql user, make it own /data/wre/prereqs/mysql recursively • Shutdown and disable any prexisting Apache or Mysql from your distro. • Remove or rename /etc/my.cnf if it exists • Run Setup • Start the WRE! What did Setup just do? • Optionally setup a demo site for you • Optionally setup a development environment for you • Optionally Setup web statistics • Downloaded and installed WebGUI Finishing up a Binary Install • Setup your cron jobs • Log Rotator • Service Monitors • Web Stats • Demo Cleanup • Use addsite script to setup a WebGUI