No. 20CV185-GPC(KSC)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPPER DECK HOBBY DIRECT APPLICATION Acct

UPPER DECK HOBBY DIRECT APPLICATION Acct # ____________ (office use only) circle one Business Name ____________________________________ Phone Number __________________ Store/ Cell / Home Please note this number will be published in the UD Store locator circle one Business Owner / Manager ______________________________ Fax Number _________________________ Business Address: ___________________________________________ e‐mail address _______________________ ___________________________________________ Store website: _______________________ Please note, Upper Deck WILL NOT ship to anywhere other than your Retail address e‐Bay ID: ____________________________ Beckett Store ID: ______________________ 1.) Is your business operated in a Retail/Commercial (non‐residential) setting? ☐Yes ☐No 2.) Do you have more than one location? ☐Yes ☐No 3.) Store Hours Monday ________ If so, please list additional addresses: Tuesday ________ ____________________________________________________________ Wednesday _______ ____________________________________________________________ Thursday _______ ____________________________________________________________ Friday _______ ____________________________________________________________ Saturday _______ Sunday ________ 4.) Please check the category that best describes your business ☐Hobby Store ☐Wholesaler ☐Case Breaker ☐Show vendor ☐Direct Mail/Online ☐Other _________ 5.) Do you wholesale product online to other dealers? ☐ Yes ☐ No. If yes, what percentage of your business is done this way? _________% 6.) Indicate the -

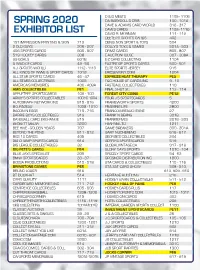

Spring 2020 Exhibitor List

D & D MEATS 1105 - 1106 SPRING 2020 DA BABYDOLL'S CRIB 100 - 101A DAVE & ADAM'S CARD WORLD 316 - 317 EXHIBITOR LIST DAVE'S CARDS 1109 - 1110 DAVID R. MORNAN 111 - 112 DEETER'S SPORTS CARDS 402 1ST IMPRESSION PRINTING & SIGN 713 DENIS NON SPORT & TOYS 504 2 OLD GUYS 206 - 207 DOLLY'S TOYS & GAMES 501A - 503 456 SPORTS CARDS 905 - 907 DRMZ CARDS 805 - 807 519 HOCKEY CARDS 308 E-AUCTIONHOUSE 307 - 308A 99 GOALS 601B E-Z CARD COLLECTING 1104 A WAD OF CARDS 48 - 50 EASTRIDGE SPORTS CARDS 500 - 501 A.J. SPORTS WORLD 1112 - 1113 ELITE SPORTS JERSEY 915 ALL KINDS OF WWE & SPORT CARDS 1018 ERICSEVIGNY.COM 1204 ALL STAR SPORTS CARDS 46 - 47 EXPRESS HEAT THERAPY PE5 ALL STARS COLLECTIBLES 1005 F&C HOUSE OF CARDS INC 9 - 10 AMERICA'S MEMORIES 406 - 408A FASTBALL COLLECTIBLES 110 AMG COLLECTIBLES PE1 FINAL SHOT SC 113 - 114 APPLETREE SPORTSCARDS 108 - 109 FOREST CITY COINS PE12 ARMY'S SPORTS COLLECTABLES 1001C-1004 FOUR J'S SPORTSCARDS 5 AUTOGRAPH NETWORK INC 815 - 816 FRAMEWORTH SPORTS 4200 B.O. PAGEAU 1009 - 1010 FRAMING LIFE 2800 BACON N EGGS 715 - 716 FRANCOIS BEAUCHESNE 27 BARRIE BOYS COLLECTIBLES 919 FRANK N BEANS 301B BASEBALL CARD EXCHANGE 215 FRANKIEFIVES 201B - 203 BECKETT MEDIA 3200 FRAPAN LTD 1211 BEE HIVE - GOLDEN YEARS 707 GAME BREAKERS 300 - 301A BEYOND THE POND 811 - 812 GARY NUCHERENO 616 - 617 BGS 10 CARDS 405 GEORGE'S COLLECTIBLES 204 BIG CHAMP SPORTS CARDS 914 GERRY'S SPORTSCARDS 519 BIG LEAGUE COLLECTABLES 32 GLOBALVINTAGE.CA 917 - 918 BIG PETE'S CARDS PE4 GLORY DAYS SPORTS 101C - 104 BLUE JAYS SPECIALIST 205 GRIZZLY SPORT CARDS 54 - 63 BMW SPORTSCARDS 33 - 37 GROSNOR DISTRIBUTION INC. -

July 2011 Prices Realized

HUGGINS & SCOTT JULY 28, 2011 PRICES REALIZED LOT# TITLE BIDS SALE PRICE 1 1968 Topps 3-D Near Set of (10/12) PSA Graded Cards with Perez & Stottlemyre 33 $16,450.00 2 1968 Topps 3-D Roberto Clemente PSA 5 25 $8,225.00 3 1968 Topps 3-D Ron Fairly (No Dugout) Variation PSA 7 8 $763.75 4 1968 Topps 3-D Jim Maloney (No Dugout) Variation PSA 6 3 $528.75 5 1968 Topps 3-D Willie Davis PSA 6 8 $381.88 6 1968 Topps 3-D Jim Lonborg PSA 8 24 $1,410.00 7 1968 Topps 3-D Jim Maloney PSA 8 12 $499.38 8 1968 Topps 3-D Tony Perez PSA 8 33 $3,525.00 9 1968 Topps 3-D Boog Powell PSA 8 30 $2,820.00 10 1968 Topps 3-D Ron Swoboda PSA 7 27 $1,997.50 11 1909-11 T206 Walter Johnson Portrait PSA EX 5 14 $1,410.00 12 (4) 1909-11 T206 White Border Ty Cobb Pose Variations-All PSA Graded 28 $3,818.75 13 (4) 1909-11 T206 Graded Hall of Famers & Stars with Lajoie & Mathewson 18 $940.00 14 (10) 1909-11 T206 White Border Graded Cards—All SGC 50-60 11 $528.75 15 (42) T205 Gold Borders & T206 White Borders with (17) Graded & (7) Hall of Famers/Southern Leaguers 21 $1,762.50 16 1912 T202 Hassan Triple Folders Egan/Mitchell PSA 7 4 $470.00 17 (37) 1919-21 W514 SGC Graded Collection with Ruth, Hornsby & Johnson--All Authentic 7 $1,292.50 18 (4) 1913 T200 Fatima Team Cards—All PSA or SGC 4 $558.13 19 (12) 1917 Collins-McCarthy SGC Graded Singles 12 $499.38 20 (7) 1934-36 Diamond Stars Semi-High Numbers—All SGC 60-80 6 $293.75 21 (18) 1934-36 Batter-Up High Numbers with (6) Hall of Famers—All SGC 60-80 12 $1,410.00 22 (5) 1940-1949 Play Ball, Bowman & Leaf Baseball Hall of -

A Review of the Post-WWII Baseball Card Industry

A Review of the Post-WWII Baseball Card Industry Artie Zillante University of North Carolina Charlotte November 25th,2007 1Introduction If the attempt by The Upper Deck Company (Upper Deck) to purchase The Topps Company, Inc. (Topps) is successful, the baseball card industry will have come full circle in under 30 years. A legal ruling broke the Topps monopoly in the industry in 1981, but by 2007 the industry had experienced a boom and bust cycle1 that led to the entry and exit of a number of firms, numerous innovations, and changes in competitive practices. If successful, Upper Deck’s purchase of Topps will return the industry to a monopoly. The goal of this piece is to look at how secondary market forces have shaped primary market behavior in two ways. First, in the innovations produced as competition between manufacturers intensified. Second, in the change in how manufacturers competed. Traditional economic analysis assumes competition along one dimension, such as Cournot quantity competition or Bertrand price competition, with little consideration of whether or not the choice of competitive strategy changes. Thus, the focus will be on the suggested retail price (SRP) of cards as well as on the timing of product releases in the industry. Baseballcardshaveundergonedramaticchangesinthepasthalfcenturyastheindustryandthehobby have matured, but the last 20 years have provided a dramatic change in the types of products being produced. Prior to World War II, baseball cards were primarily used as premiums or advertising tools for tobacco and candy products. Information on the use of baseball cards as advertising tools in the tobacco and candy industries prior to World War II can be obtained from a number of different sources, including Kirk (1990) and most of the annual comprehensive baseball card price guides produced by Beckett publishing. -

Hoofdblad IE 26 Juni 2019

Nummer 26/19 26 juni 2019 Nummer 26/19 2 26 juni 2019 Inleiding Introduction Hoofdblad Patent Bulletin Het Blad de Industriële Eigendom verschijnt The Patent Bulletin appears on the 3rd working op de derde werkdag van een week. Indien day of each week. If the Netherlands Patent Office Octrooicentrum Nederland op deze dag is is closed to the public on the above mentioned gesloten, wordt de verschijningsdag van het blad day, the date of issue of the Bulletin is the first verschoven naar de eerstvolgende werkdag, working day thereafter, on which the Office is waarop Octrooicentrum Nederland is geopend. Het open. Each issue of the Bulletin consists of 14 blad verschijnt alleen in elektronische vorm. Elk headings. nummer van het blad bestaat uit 14 rubrieken. Bijblad Official Journal Verschijnt vier keer per jaar (januari, april, juli, Appears four times a year (January, April, July, oktober) in elektronische vorm via www.rvo.nl/ October) in electronic form on the www.rvo.nl/ octrooien. Het Bijblad bevat officiële mededelingen octrooien. The Official Journal contains en andere wetenswaardigheden waarmee announcements and other things worth knowing Octrooicentrum Nederland en zijn klanten te for the benefit of the Netherlands Patent Office and maken hebben. its customers. Abonnementsprijzen per (kalender)jaar: Subscription rates per calendar year: Hoofdblad en Bijblad: verschijnt gratis Patent Bulletin and Official Journal: free of in elektronische vorm op de website van charge in electronic form on the website of the Octrooicentrum Nederland. -

M&A Notes July 2007:M&A Notes June 2007

KIRKLAND & ELLIS LLP M&A NOTES July 2007 Topps Decision: Delaware Chancery Court Invalidates Standstill Agreement Preventing Competing Bidder From Making a Topping Tender Offer and Full Disclosure of Relevant Facts Surrounding Merger In the recent case of In re: The Topps Company Shareholders Litigation,1 the Delaware Chancery Court, in a decision by Vice Chancellor Strine, held that the board of directors of The Topps Company most likely breached its fiduciary duties by misusing a standstill agreement with The Upper Deck Company to prevent it from making a non-coercive tender offer for Topps’ outstanding shares at a higher price than that provided for in a merger agreement between Topps and an entity affiliated with Michael Eisner. Consequently, the Court issued an injunction enjoining the Topps’ shareholder vote on the pending merger until such time as Upper Deck is released from the standstill agreement to permit it to make a tender offer for Topps and to publicly comment on its negotiations with Topps. The Court also enjoined the Topps’ shareholder vote on the merger until Topps discloses several material facts not contained in the merger proxy, including facts regarding assurances given by Eisner that existing management would be retained after the merger. For the reasons discussed below, the decision is significant for all M&A practitioners. The Facts Background The Topps Company (“Topps” or the “Company”) is a Delaware public company that makes baseball cards and bubble gum. The chairman and CEO of Topps (“Shorin”) is the son of the one of the founders of the Company and owns approximately 7% of the outstanding equity of the Company, and the president and COO is Shorin’s son-in-law. -

Upper Deck Trading Card Products Sweepstakes

UPPER DECK TRADING CARD PRODUCTS SWEEPSTAKES OFFICIAL RULES NO PURCHASE NECESSARY TO ENTER OR WIN. WINNER MAY BE REQUIRED TO RESPOND TO THE WINNER NOTIFICATION AND/OR COMPLETE AND EXECUTE A RELEASE, PRIZE ACCEPTANCE AGREEMENT, AND ANY OTHER DOCUMENTS WITHIN THE TIME FRAME REQUIRED BY SPONSOR OR PRIZE MAY BE FORFEITED (IN SPONSOR’S SOLE DISCRETION). BY ENTERING THIS CONTEST (“SWEEPSTAKES”), YOU AGREE TO THESE OFFICIAL RULES, WHICH ARE A CONTRACT, SO READ THEM CAREFULLY BEFORE ENTERING. EXCLUDING QUEBEC: WITHOUT LIMITATION, THIS CONTRACT INCLUDES INDEMNIFICATION OBLIGATIONS FROM YOU TO THE SPONSOR AND A LIMITATION OF YOUR RIGHTS AND REMEDIES. 1. NAME OF CONTEST: Upper Deck Trading Card Products (individually a “Product” or collectively the “Products”) 2. SPONSOR: This Sweepstakes is sponsored by The Upper Deck Company, 5830 El Camino Real, Carlsbad, California 92008 (“UDC” or “Upper Deck”) ( “Sponsor”). 3. SWEEPSTAKES PERIOD: Please see individual Product details located at http://sports.upperdeck.com/npn/ (the “Website’). 4. ELIGIBILITY: This sweepstakes (the “Sweepstakes”) is open and offered only to legal residents of the fifty (50) United States (including D.C. but excluding Puerto Rico, New York, Rhode Island, and Florida) and the provinces and territories of Canada (excluding Quebec) who have reached the age of majority in their jurisdiction of residence and are at least eighteen (18) years old by or before the date specified for the particular product, found at http://sports.upperdeck.com/npn/. Officers, directors, employees, representatives -

2010 1:22 PM Page 1

April 10 COF C1:COF C1.qxd 3/18/2010 1:22 PM Page 1 ORDERS DUE th 10APR 2010 APR E E COMIC H H T T SHOP’S CATALOG Project7:Layout 1 3/15/2010 1:35 PM Page 1 COF Gem Page Apr:gem page v18n1.qxd 3/18/2010 2:07 PM Page 1 PREDATORS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS BUZZARD #1 DARK HORSE COMICS GREEN ARROW #1 DC COMICS SUPERMAN #700 DC COMICS JURASSIC PARK: REDEMPTION #1 IDW PUBLISHING HACK/SLASH: MY FIRST MANIAC #1 MAGAZINE GEM OF THE MONTH IMAGE COMICS THE BULLETPROOF COFFIN #1 IMAGE COMICS WIZARD MAGAZINE #226 THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN #634 MARVEL COMICS COF FI page:FI 3/18/2010 2:14 PM Page 1 FEATURED ITEMS COMICS 1 THE ROYAL HISTORIAN OF OZ #1 G AMAZE INK/ SLAVE LABOR GRAPHICS CRITICAL MILLENNIUM #1 G ARCHAIA ENTERTAINMENT LLC DARKWING DUCK: THE DUCK KNIGHT RETURNS #1 G BOOM! STUDIOS DISNEY‘S ALICE IN WONDERLAND GN/HC G BOOM! STUDIOS RED SONJA #50 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT STARGATE: DANIEL JACKSON #1 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 1 GHOSTOPOLIS SC/HC G GRAPHIX THE WHISPERS IN THE WALLS #1 G HUMANOIDS INC STARDROP VOLUME 1 GN G I BOX PUBLISHING KRAZY KAT: A CELEBRATION OF SUNDAYS HC G SUNDAY PRESS BOOKS SIMON & KIRBY SUPERHEROES HC G TITAN PUBLISHING THE PLAYWRIGHT HC G TOP SHELF PRODUCTIONS CHARMED #1 G ZENESCOPE ENTERTAINMENT INC BOOKS & MAGAZINES WILLIAM STOUT: HALLUCINATIONS SC/HC G ART BOOKS 2 SUCK IT, WONDER WOMAN! MISADVENTURES OF A HOLLYWOOD GEEK G HUMOR ASLAN: THE PIN-UP SC G INTERNATIONAL STAR WARS: THE OFFICIAL FIGURINE COLLECTION MAGAZINE G STAR WARS TOYFARE #156 G WIZARD ENTERTAINMENT CALENDARS 2 BONE 2011 WALL CALENDAR G COMICS VINTAGE -

Consignment Auction March 2018 3/31/2018 LOT # QTY 1 Oliver

Consignment Auction March 2018 3/31/2018 LOT # QTY LOT # QTY 301 Oliver Manure Spreader 1 320 Wooden End Table 1 Ne Ne 302 Dresser 1 321 Wooden End Table 1 Ne Ne 303 Table top Pool Set 1 322 Table Top Podium 1 Ne Ne 304 Dresser 1 323 Computer, printer and accessories 1 Ne Ne 305 Coffee Table 1 324 Large Wooden Table 1 Ne Ne 306 Box Lot with lantern, spotlight, phone 1 325 Wooden Coffee Table 1 Ne Ne 307 Box Lot with VHS Tapes 1 326 Bookcase 1 Ne Ne 308 Portable Battery - TV / Lantern Combo 1 327 Bookcase 1 Ne Ne 309 Wall Mount Gun Rack 1 328 Bookcase 1 Ne Ne 310 Set of two wooden chairs 1 329 Hinged top wooden table with storage 1 Ne Ne 311 Box Lot with VHS Player, glass globes 1 330 Dining table with leaf 1 Ne Ne 312 Eureka Upright Vacuum 1 331 Wooden Chair 1 Ne Ne 313 Stamina 4755 Recumbant Exercise Bike 1 332 Rolling drop leaf table 1 Ne Ne 314 Collapseable Jewelry Armoire 1 333 Coffee Table 1 Ne Ne 315 Five piece Bedroom Set 1 334 Metal Decorative truck 1 Ne Dresser, Chest, Queen Bed and Two Night Stands Ne 335 Metal decorative wagon 1 316 Four Piece Bedroom Set 1 Ne Ne Double Bed, Dresser, Chest and one nightstand 336 Outdoor chair cushions and rug 1 Ne 317 Christmas Wall Art 1 337 Coffee table 1 Ne Ne 318 Office Chair 1 338 Buffett and China cabinet 1 Ne Ne 319 Dining Table 1 Ne Items listed in this catalog may change without notice, per the Consigner. -

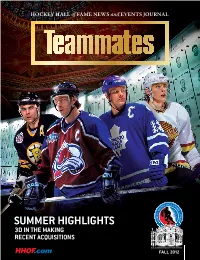

Summer Highlights 3D in the Making Recent Acquisitions

HOCKEY HALL of FAME NEWS and EVENTS JOURNAL > SUMMER HIGHLIGHTS 3D IN THE MAKING RECENT ACQUISITIONS FALL 2012 Letter from the Chairman & CEO On June 26, 2012 our esteemed Selection Committee met and Friday, November 9, 2012 deliberated on candidates for The public launch of the Hockey Hall of Fame’s newest feature film, Stanley’s Game Seven (3D). Ben Welland/HHOF-IIHF Images Ben Welland/HHOF-IIHF the 2012 Induction. We are very pleased to congratulate hockey’s newest leg- 7:00pm ends, Pavel Bure, Adam Oates, Joe Sakic and Mats Hockey Hall of Fame Game Sundin, on their upcoming Induction set for Monday, Air Canada Centre New Jersey Devils vs. Toronto Maple Leafs November 12th. This year’s Inductee announcement was broadcast live for the second year on TSN, and for the first time ever, the Official Hockey Hall of Fame Saturday, November 10, 2012 Game (Devils vs. Leafs) is scheduled for TSN broadcast A special 2012 Limited Edition Inductee Poster will be distributed to guests upon entry to the Hockey Hall of Fame. The first 500 patrons will receive a poster autographed by on Friday, November 9th. the 2012 Inductees. We also congratulate the Los Angeles Kings on 1:30 – 4:00pm 1972 Summit Series Fan Forums becoming the Stanley Cup Champions for the 2011-2012 A series of Q & A sessions, hosted by Ron Ellis, celebrating the 40th anniversary of season. It seems fitting that since the Cup has “gone the historic tournament. Hollywood” so has its home - the Hockey Hall of Fame. We have teamed up with Network Entertainment Inc. -

Upper Deck Releases High Series Just in Time for Overwatch League™ Grand Finals

UPPER DECK RELEASES HIGH SERIES JUST IN TIME FOR OVERWATCH LEAGUE™ GRAND FINALS Upper Deck to offer exclusive content, free trading cards and new Overwatch League High Series product at sold-out Grand Finals in Philadelphia! CARLSBAD, Calif, - September 25, 2019 - Upper Deck, the premier worldwide sports and entertainment collectibles company, announced today the global launch of Overwatch League™ High Series. The new update set marks the second esports trading card product from Upper Deck and comes off the heels of the first-ever esports league-licensed trading card set released by the company earlier this summer. The High Series product adds content from the league’s eight expansion teams, along with 90 new rookies from across the entire league. The new release comes just in time for the sold-out Overwatch League Grand Finals taking place at Wells Fargo Center in Philadelphia this weekend. In celebration of the event and the new product launch, Upper Deck will be offering free sample packs and exclusive Grand Finals-themed digital content to all fans in attendance, as well as the opportunity to have a personalized Overwatch League trading card created onsite. The company will also host a trading zone at the Grand Finals Fan Fest event where fans can trade cards with Upper Deck staff and get a first-hand look at samples of some rare inserts and achievements from the new Overwatch League card set. Upper Deck’s new Overwatch League High Series set includes never-before-seen hits and chase cards, including foil-etched Star Rookies cards, multi-player jersey Fragment booklet cards, player-autographed Ink insert cards, clear acetate Infra-Sight player cards and rare Holo F/X insert cards. -

Official Rulebook Nv 89030 Usa

Ready Draw Step Step • Play Cards Combat • Use Powers Step(s) • Place a Resource • Make Attacks Wrap-Up Step ©2006 The Upper Deck Company All rights reserved. The Upper Deck Company 985 Trade Drive, N. Las Vegas, OFFICIAL RULEBOOK NV 89030 USA. Upper Deck Europe BV, Flevolaan 15, 1382 JX Weesp, The Netherlands. All rights reserved. © 2006 Blizzard Entertainment, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Warcraft, World of Warcraft and Blizzard Entertainment are trademarks and/or registered trademarks of Blizzard Entertainment, Inc. in the U.S. and/or other countries. All other trademarks referenced herein are the properties of their respective owners. Deckbuilding Quick Reference here are only a few rules you need to follow when building your deck: T ❂ Your deck must include at least 60 cards, not counting your starting hero. Your hero starts the game in play, and it isn’t considered a part of your deck. ❂ You can’t include more than four copies of a single card in your deck unless that card has “unlimited” in its type line. You may include any number of unlimited cards in your deck. ❂ Some ability cards can only be used by a hero who has a certain talent spec. Those cards will have “[Talent Spec] Hero Required” in bold in their text box. ❂ You can include only cards that share one or more trait icons with your hero in your deck. Some neutral cards don’t have any trait icons. You can put those cards into any deck. Check out the WoW TCG websites: UDE.com/wow, WoWRealms.com, WoWCards.org, WoW.TCGPlayer.com, WarcraftCCG.com, WoWTCGDB.com Table of Contents Introduction ........................