William Merritt Chase and Carmel (1914)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE ARTIST's EYES a Resource for Students and Educators ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

THE ARTIST'S EYES A Resource for Students and Educators ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is with great pleasure that the Bowers Museum presents this Resource Guide for Students and Educators with our goal to provide worldwide virtual access to the themes and artifacts that are found in the museum’s eight permanent exhibitions. There are a number of people deserving of special thanks who contributed to this extraordinary project. First, and most importantly, I would like to thank Victoria Gerard, Bowers’ Vice President of Programs and Collections, for her amazing leadership; and, the entire education and collections team, particularly Laura Belani, Mark Bustamante, Sasha Deming, Carmen Hernandez and Diane Navarro, for their important collaboration. Thank you to Pamela M. Pease, Ph.D., the Content Editor and Designer, for her vision in creating this guide. I am also grateful to the Bowers Museum Board of Governors and Staff for their continued hard work and support of our mission to enrich lives through the world’s finest arts and cultures. Please enjoy this interesting and enriching compendium with our compliments. Peter C. Keller, Ph.D. President Bowers Museum Cover Art Confirmation Class (San Juan Capistrano Mission), c. 1897 Fannie Eliza Duvall (1861-1934) Oil on canvas; 20 x 30 in. Bowers Museum 8214 Gift of Miss Vesta A. Olmstead and Miss Frances Campbell CALIFORNIA MODULE ONE: INTRO / FOCUS QUESTIONS 5 MODULE FOUR: GENRE PAINTING 29 Impressionism: Rebels and Realists 5 Cityscapes 30 Focus Questions 7 Featured Artist: Fannie Eliza Duvall 33 Timeline: -

George Bellows on Monhegan Island

David Peters Corbett The World Is Terrible and It Is Not There at All: George Bellows on Monhegan Island Painted on Monhegan Island off the coast of Maine during the summer of 1913, George Bellows’s small oil on panel Churn and Break (fig. 1) depicts a shore and its surrounding sea. The observer’s gaze encounters a mound of dark, almost black, rocks, which glisten with trails of moisture and light. To the left, the sea, sweeping in a great wave up against the rocks, threatens to overtop the ridge. In the midground, further dramatic swells rise and fall, and overhead, in a dreary sky, Bellows’s paint describes the insistent perpendicular fall of rain. Above the rocks and to the right, a plume of spray, dense and gray and white, jets up in a balletic swirl of creamy pigment. Bellows’s painting uses dazzling mixed brushwork to portray the variety of forms and textures of this scene, from the fluid lines and sinuous handling of the fore- ground sea to the dragged marks that describe the descending curtain of rain and cast a shadowy veil across the distance. The world we are confronted by in Churn and Break seems to fall into two disparate levels of experience: on the one hand, a discrete, self-contained universe of vital but inhuman matter, formed by the crashing sea and mute shoreline; on the other, an intimately human domain, the gestural runs and virtuoso flourishes of Bellows’s hand and brush.1 Despite this apparently radical division, the two levels also merge fleetingly into a single identity. -

Finding Aid for the John Sloan Manuscript Collection

John Sloan Manuscript Collection A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum The John Sloan Manuscript Collection is made possible in part through funding of the Henry Luce Foundation, Inc., 1998 Acquisition Information Gift of Helen Farr Sloan, 1978 Extent 238 linear feet Access Restrictions Unrestricted Processed Sarena Deglin and Eileen Myer Sklar, 2002 Contact Information Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives Delaware Art Museum 2301 Kentmere Parkway Wilmington, DE 19806 (302) 571-9590 [email protected] Preferred Citation John Sloan Manuscript Collection, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum Related Materials Letters from John Sloan to Will and Selma Shuster, undated and 1921-1947 1 Table of Contents Chronology of John Sloan Scope and Contents Note Organization of the Collection Description of the Collection Chronology of John Sloan 1871 Born in Lock Haven, Pennsylvania on August 2nd to James Dixon and Henrietta Ireland Sloan. 1876 Family moved to Germantown, later to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. 1884 Attended Philadelphia's Central High School where he was classmates with William Glackens and Albert C. Barnes. 1887 April: Left high school to work at Porter and Coates, dealer in books and fine prints. 1888 Taught himself to etch with The Etcher's Handbook by Philip Gilbert Hamerton. 1890 Began work for A. Edward Newton designing novelties, calendars, etc. Joined night freehand drawing class at the Spring Garden Institute. First painting, Self Portrait. 1891 Left Newton and began work as a free-lance artist doing novelties, advertisements, lettering certificates and diplomas. 1892 Began work in the art department of the Philadelphia Inquirer. -

254 CHAPTER 10 Proportion CHAPTER 10 Proportion

ᮡ FIGURE 10.1 This painting is a fresco. Italian for “fresh,” fresco is an art technique in which paint is applied to a fresh, or wet, plaster surface. Examine the size of the figures depicted in this fresco. Is this depiction always realistic? Diego Rivera. The Making of a Fresco Showing the Building of a City. 1931. Fresco. 6.9 x 9 m (22’7” ϫ 29’9”). Located at the San Francisco Art Institute, San Francisco, California. Gift of William Gerstle. 254 CHAPTER 10 Proportion CHAPTER 10 Proportion ou may be taller than some students in your art class, Yshorter than others. Distinctions like these involve proportion, or relative size. As an art principle, proportion can direct the viewer’s eye to a specific area or object in an artwork. In this chapter, you will: Explain and recognize the Golden Mean. Identify scale and proportion in artworks. Create visual solutions using direct observation to reflect correct human proportions. Compare and contrast the use of proportion in personal artworks and those of others. Figure 10.1 was painted by the Mexican artist Diego Rivera (1886–1957). At age 21, Rivera went to study art in Europe, where he met Paul Cézanne and Pablo Picasso. Returning to Mexico in 1921, Rivera rejected what he had learned. He chose instead to imitate the simplified forms of his pre-Columbian ancestors in Mexico. Rivera also became a champion of the rights of the working class. Social themes inspired him to create large mural paintings. His murals, which adorn the walls of public buildings, all have political or historical themes. -

Bellows, George Also Known As Bellows, George Wesley American, 1882 - 1925

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS American Paintings, 1900–1945 Bellows, George Also known as Bellows, George Wesley American, 1882 - 1925 Peter A. Juley & Son, George Bellows, c. 1920, photograph, 1913 Armory Show, 50th anniversary exhibition records, 1962–1963, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution BIOGRAPHY George Bellows was born in Columbus, Ohio, on August 12, 1882, the only child of a successful building contractor from Sag Harbor, Long Island, New York. He entered Ohio State University in 1901, where he played baseball and basketball and made drawings for college publications. He dropped out of college in 1904, went to New York, and studied under Robert Henri (American, 1865 - 1929) at the New York School of Art, where Edward Hopper (American, 1882 - 1967), Rockwell Kent (American, 1882 - 1971), and Guy Pène du Bois (American, 1884 - 1958) were his classmates. A superb technician who worked in a confident, painterly style, Bellows soon established himself as the most important realist of his generation. He created memorable images of club fights, street urchins swimming in the East River, and the Pennsylvania Station excavation site and garnered praise from both progressive and conservative critics. In 1909 he became one of the youngest artists ever admitted as an associate member of the National Academy of Design. In 1910 Bellows began teaching at the Art Students League and married Emma Story, by whom he had two daughters. After 1910 Bellows gradually abandoned the stark urban realism and dark palette characteristic of his early work and gravitated toward painting landscapes, seascapes, and portraits. -

Henrietta Shore in Point Lobos and Carmel

HENRIETTA SHORE IN POINT LOBOS AND CARMEL: SPIRIT OF PLACE, ESSENCE OF BEING by MINA TOCHEVA STOEVA (Under the Direction of Janice Simon) ABSTRACT Shore’s visual vocabulary developed from Impressionism towards more stylized, abstracted forms in her 1920s work, and after 1930 culminated in the textured, detailed and almost tactile drawings produced in Carmel, California. This thesis focuses on the impact that Carmel had on her personal and artistic life. A detailed analysis of Shore’s images of the Monterey Peninsula establishes the connection between her extended visual narrative of the locale and the tradition of written ecocentric narratives. I will consider the Theosophical and transcendental ideas that Shore expressed in her work and relate them to Lawrence Buell’s theory of ecocentric narrative. By unveiling the subtleties of such a narrative and the process of its creation, the present analysis will further our understanding of Shore’s deeply emotional and spiritual attachment to the Monterey Peninsula. More than merely depicting a peculiar landscape, Shore’s late drawings reveal her preoccupation with current literary and philosophical trends, while simultaneously creating an intimate reflection of the artist’s self. INDEX WORDS: Henrietta Shore (1880-1962), Carmel, Point Lobos, landscape, transcendentalism, Ralph Waldo Emerson, place, ecocentric narrative, Theosophy, self-portrait, American modernism, Johann Wolfgang Goethe HENRIETTA SHORE IN POINT LOBOS AND CARMEL: SPIRIT OF PLACE, ESSENCE OF BEING by MINA TOCHEVA STOEVA BA, -

Download the Preview Catalog

#JANMgala Japanese American National Museum 2018 Silent Auction Catalog As of 4/10/18 Japanese American National Museum Silent Auction Rules and Reminders Please be sure to get your Silent Auction Bid Number from the Registration Table. Silent Auction Rules Items and packages in this Silent Auction Catalog are subject to change. Images are provided as a courtesy to our guests only and are not necessarily an accurate depiction of the quality of a given item. The National Museum does not assume responsibility for the accuracy of any description. Unless otherwise stated, all items and services are valid within one year from April 21, 2018. All services must be redeemed by the listed expiration date. The National Museum and the donor cannot extend the expiration date of any service. Read all auction package descriptions carefully as they list specific restrictions. Please be aware. If you would like to extend your stay, you must coordinate with the donor directly. Auction Coordinators do not make travel arrangements. All items are sold “as is”, are subject to availability, and have no cash redemption value. The National Museum is grateful to our donors, but is unable to endorse any product or service. The stated value of auction goods and services are good-faith estimates only and are not warranted for tax purposes. Please contact your tax advisor regarding the tax deductibility of purchases and contributions. Any amount over the stated market value of an item may be tax deductible. The National Museum is not responsible for lost or stolen certificates/vouchers. The National Museum assumes no responsibility should any of the donating establishments be unable to fulfill gift certificates. -

A Stellar Century of Cultivating Culture

COVERFEATURE THE PAAMPROVINCETOWN ART ASSOCIATION AND MUSEUM 2014 A Stellar Century of Cultivating Culture By Christopher Busa Certainly it is impossible to capture in a few pages a century of creative activity, with all the long hours in the studio, caught between doubt and decision, that hundreds of artists of the area have devoted to making art, but we can isolate some crucial directions, key figures, and salient issues that motivate artists to make art. We can also show why Provincetown has been sought out by so many of the nation’s notable artists, performers, and writers as a gathering place for creative activity. At the center of this activity, the Provincetown Art Associ- ation, before it became an accredited museum, orga- nized the solitary efforts of artists in their studios to share their work with an appreciative pub- lic, offering the dynamic back-and-forth that pushes achievement into social validation. Without this audience, artists suffer from lack of recognition. Perhaps personal stories are the best way to describe PAAM’s immense contribution, since people have always been the true life source of this iconic institution. 40 PROVINCETOWNARTS 2014 ABOVE: (LEFT) PAAM IN 2014 PHOTO BY JAMES ZIMMERMAN, (righT) PAA IN 1950 PHOTO BY GEORGE YATER OPPOSITE PAGE: (LEFT) LUCY L’ENGLE (1889–1978) AND AGNES WEINRICH (1873–1946), 1933 MODERN EXHIBITION CATALOGUE COVER (PAA), 8.5 BY 5.5 INCHES PAAM ARCHIVES (righT) CHARLES W. HAwtHORNE (1872–1930), THE ARTIST’S PALEttE GIFT OF ANTOINETTE SCUDDER The Armory Show, introducing Modernism to America, ignited an angry dialogue between conservatives and Modernists. -

The Elegant Home

THE ELEGANT HOME Select Furniture, Silver, Decorative and Fine Arts Monday November 13, 2017 Tuesday November 14, 2017 Los Angeles THE ELEGANT HOME Select Furniture, Silver, Decorative and Fine Arts Monday November 13, 2017 at 10am Tuesday November 14, 2017 at 10am Los Angeles BONHAMS BIDS INQUIRIES Automated Results Service 7601 W. Sunset Boulevard +1 (323) 850 7500 European Furniture and +1 (800) 223 2854 Los Angeles, California 90046 +1 (323) 850 6090 fax Decorative Arts bonhams.com Andrew Jones ILLUSTRATIONS To bid via the internet please visit +1 (323) 436 5432 Front cover: Lot 215 (detail) PREVIEW www.bonhams.com/24071 [email protected] Day 1 session page: Friday, November 10 12-5pm Lot 733 (detail) Saturday, November 11 12-5pm Please note that telephone bids American Furniture and Day 2 session page: Sunday, November 12 12-5pm must be submitted no later Decorative Arts Lot 186 (detail) than 4pm on the day prior to Brooke Sivo Back cover: Lot 310 (detail) SALE NUMBER: 24071 the auction. New bidders must +1 (323) 436 5420 Lots 1 - 899 also provide proof of identity [email protected] and address when submitting CATALOG: $35 bids. Telephone bidding is only Decorative Arts and Ceramics available for lots with a low Jennifer Kurtz estimate in excess of $1000. +1 (323) 436 5478 [email protected] Please contact client services with any bidding inquiries. Silver and Objects of Vertu Aileen Ward Please see pages 321 to 323 +1 (323) 436 5463 for bidder information including [email protected] Conditions of Sale, after-sale collection, and shipment. -

Adiant P Ressions

Radiant Impressions Note to Teachers UCI Institute and Museum of California Art (IMCA) aims to be a resource to educators and students by offering school visits, programs, digital tools, and activities designed for grades 3–12 that contribute to the development of stronger critical-thinking skills, empathy, and curiosity about art and culture. When students are encouraged to express themselves and take risks in discussing and creating art, they awaken their imaginations and nurture their creative and innovative potential. School visits offer opportunities for students to develop observation and interpretation skills using visual and sensory information, build knowledge independently and with one another, and cultivate an interest in artistic production. This Teacher Resource Guide includes essays, artist biographies, strategies for interdisciplinary curriculum integration, discussion questions, methods for teaching with objects, a vocabulary list, and activities for three works in IMCA’s collection that are included in the exhibition Radiant Impressions. About the Exhibition From California Impressionism to the Light and Space movement, California artists have been celebrated for their skillful rendering of the perceptual effects of light. Focusing on painters working in California throughout the 20th century, Radiant Impressions considers the ways these artists have engaged with light not only for its optical qualities Radiant Impressions but also for its power to infuse ephemeral moments with meaning and emotion. Whether the warm golden tones of the California sun or the intense glow of electric bulbs, light in these paintings communicates a sense of anticipation, celebration, rest, and reflection. Presenting works organized in thematic groupings—The Domestic Realm and Work, Capturing the Scene, Play and the Social Sphere, and Lighting the Portrait—the exhibition brings together a diverse selection of landscapes and portraiture as well as genre scenes depicting people at work and at play. -

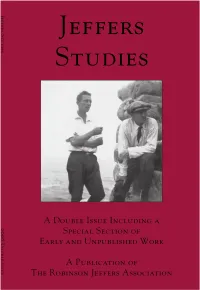

Numbers 1 & 2 Spring & Fall 2008

Jeffers Studies Volume 12 Numbers 1 & 2 Spring & Fall 2008 A Double Issue Including a Special Section of Early and Unpublished Work Contents Editor’s Note iii Articles Kindred Poets of Carmel: The Philosophical and Aesthetic Affinities of George Sterling and Robinson Jeffers John Cusatis 1 The Ghost of Robinson Jeffers Temple Cone 13 Jeffers’s Isolationism Robert Zaller 27 Special Section of Early and Unpublished Work The Collected Early Verse of Robinson Jeffers: A Supplement Robert Kafka 43 Haunted Coast Dirk Aardsma, Transcriber and Editor 57 Book Review The Collected Letters of Robinson Jeffers with Selected Letters of Una Jeffers, Volume One, 1890 –1930 Reviewed by Gere S. diZerega, M.D. 77 News and Notes 93 Contributors 99 Cover photo: Robinson Jeffers and George Sterling, c. 1926. Courtesy Jeffers Literary Properties. George Hart Editor’s Note This double issue of volume 12 of Jeffers Studies continues our commit- ment to present readers with original Jeffers material—photos, drafts, unpublished and obscure work, and so on—that will aid and enhance scholarship and interest readers in general. The special section in this volume contains two such items: a supplement to The Collected Early Verse and a transcription of an unpublished manuscript from Occidental College’s Jeffers collection. Robert Kafka has unearthed eight poems from Jeffers’s early years that have never before been collected. Four of the poems originally appeared in The Los Angeles Times, and the other four were included in correspondence or uncatalogued archival collec- tions. One manuscript was given to a one-time girlfriend, and we are happy to reproduce an image of it and a photo of the young lady, Vera Placida Gardner. -

A Finding Aid to the Raymond and Margaret Horowitz Papers, 1903-2007, Bulk 1960-2007, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Raymond and Margaret Horowitz Papers, 1903-2007, bulk 1960-2007, in the Archives of American Art Joy Goodwin 2015 May 3 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: Art Collection Files, 1943-2007................................................................ 4 Series 2: Artwork, Sold, or Donated, 1903, 1950-2003........................................... 9 Series 3: Accession Records, 1959-circa 1994..................................................... 17 Series 4: Catalog Information, circa 1960-1967....................................................