Jae Jarrell Was Born in Cleveland in Addition of a Colorful Bandolier

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Group Interview with Africobra Founders

Group interview with AfriCOBRA founders Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The original format for this document is Microsoft Word 11.5.3. Some formatting has been lost in web presentation. Speakers are indicated by their initials. Interview Group Interview Part 1 AFRICOBRA Interviews Tape GR3 TV LAND GROUP INTERVIEW: BARBARA JONES HOGU, NAPOLEON JONES HENDERSON, HOWARD MALLORY, CAROLYN LAWRENCE, MICHAEL HARRIS Note: Question difficult to hear at times. Also has heavy accent. BJH: I don't think (Laughter) ... I don't think the Wall of Respect motivated AFRICOBRA. The Wall of Respect started first, and it was only after that ended that Jeff called some of the artists together and ordered to start working on the idea of philosophy in terms of creating imagery. You know, recently I read an article that said that the AFRICOBRA started at the Wall of Respect and I'd ... it's just said that some of the artists that worked on the Wall of Respect became AFRICOBRA members. You know, but the conception of AFRICOBRA did not start at the Wall of Respect. MH: How different was it than OBAC? What was going on in OBAC? BJH: Well, OBAC is what created the Wall of Respect. MH: Right. Q: Right. BJH: Yeah, that was dealing with culture. MH: But in terms of the outlook of the artists and all of that, how different was OBAC's outlook than what came to be AFRICOBRA? BJH: Well, OBAC didn't have a philosophy, per se. -

Discovering the Contemporary

of formalist distance upon which modernists had relied for understanding the world. Critics increasingly pointed to a correspondence between the formal properties of 1960s art and the nature of the radically changing world that sur- rounded them. In fact formalism, the commitment to prior- itizing formal qualities of a work of art over its content, was being transformed in these years into a means of discovering content. Leo Steinberg described Rauschenberg’s work as “flat- bed painting,” one of the lasting critical metaphors invented 1 in response to the art of the immediate post-World War II Discovering the Contemporary period.5 The collisions across the surface of Rosenquist’s painting and the collection of materials on Rauschenberg’s surfaces were being viewed as models for a new form of realism, one that captured the relationships between people and things in the world outside the studio. The lesson that formal analysis could lead back into, rather than away from, content, often with very specific social significance, would be central to the creation and reception of late-twentieth- century art. 1.2 Roy Lichtenstein, Golf Ball, 1962. Oil on canvas, 32 32" (81.3 1.1 James Rosenquist, F-111, 1964–65. Oil on canvas with aluminum, 10 86' (3.04 26.21 m). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. 81.3 cm). Courtesy The Estate of Roy Lichtenstein. New Movements and New Metaphors Purchase Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alex L. Hillman and Lillie P. Bliss Bequest (both by exchange). Acc. n.: 473.1996.a-w. Artists all over the world shared U.S. -

Art for People's Sake: Artists and Community in Black Chicago, 1965

Art/African American studies Art for People’s Sake for People’s Art REBECCA ZORACH In the 1960s and early 1970s, Chicago witnessed a remarkable flourishing Art for of visual arts associated with the Black Arts Movement. From the painting of murals as a way to reclaim public space and the establishment of inde- pendent community art centers to the work of the AFRICOBRA collective People’s Sake: and Black filmmakers, artists on Chicago’s South and West Sides built a vision of art as service to the people. In Art for People’s Sake Rebecca Zor- ach traces the little-told story of the visual arts of the Black Arts Movement Artists and in Chicago, showing how artistic innovations responded to decades of rac- ist urban planning that left Black neighborhoods sites of economic depres- sion, infrastructural decay, and violence. Working with community leaders, Community in children, activists, gang members, and everyday people, artists developed a way of using art to help empower and represent themselves. Showcas- REBECCA ZORACH Black Chicago, ing the depth and sophistication of the visual arts in Chicago at this time, Zorach demonstrates the crucial role of aesthetics and artistic practice in the mobilization of Black radical politics during the Black Power era. 1965–1975 “ Rebecca Zorach has written a breathtaking book. The confluence of the cultural and political production generated through the Black Arts Move- ment in Chicago is often overshadowed by the artistic largesse of the Amer- ican coasts. No longer. Zorach brings to life the gorgeous dialectic of the street and the artist forged in the crucible of Black Chicago. -

Wadsworth Jarrell B

Wadsworth Jarrell B. 1929 ALBANY, GEORGIA LIVES AND WORKS IN CHICAGO EDUCATION 1958 BA School of the Art Institute of Chicago 1973 MFA Howard University, Washington, DC SELECT EXHIBITIONS 2020 Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, Museum of Fine Arts Houston, TX, USA Duro Olowu: Seeing Chicago, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Chicago, IL Figure in Solitude, online exhibition, Kavi Gupta, Chicago, IL Radical Optimism, online exhibition, Kavi Gupta, Chicago, IL Tell Me Your Story, Kunsthal KAde, Amersfoort, Netherlands 2019 Come Saturday Punch, Kavi Gupta, Chicago, IL, USA AFRICOBRA: Nation Time, Venice Biennale (official collateral exhibition), Venice, Italy Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, The Broad, Los Angeles, CA 2018 AFRICOBRA 50, Kavi Gupta, Chicago, IL USA AFRICOBRA: Messages to the People, Museum of Contemporary Art North Miami, Miami, FL The Time is Now! Art Worlds of Chicago’s South Side, 1960-1980, Smart Museum of Art, Chicago, IL Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85, ICA Boston. Boston, MA Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville , AR AFRICOBRA:Now, Kravets Wehby Gallery, New York, NY Heritage: Wadsworth and Jae Jarrell, The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, OH 2017 Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, Tate Modern, London, UK IFDPA Fine Art Print Fair 2017, Aaron Galleries, New York, NY We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, -

Here May Is Not Rap Be Music D in Almost Every Major Language,Excerpted Including Pages Mandarin

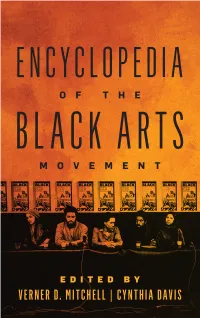

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT ed or printed. Edited by istribut Verner D. Mitchell Cynthia Davis an uncorrected page proof and may not be d Excerpted pages for advance review purposes only. All rights reserved. This is ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • London 18_985_Mitchell.indb 3 2/25/19 2:34 PM ed or printed. Published by Rowman & Littlefield An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 istribut www.rowman.com 6 Tinworth Street, London, SE11 5AL, United Kingdom Copyright © 2019 by The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Mitchell, Verner D., 1957– author. | Davis, Cynthia, 1946– author. Title: Encyclopedia of the Black Arts Movement / Verner D. Mitchell, Cynthia Davis. Description: Lanhaman : uncorrectedRowman & Littlefield, page proof [2019] and | Includes may not bibliographical be d references and index. Identifiers:Excerpted LCCN 2018053986pages for advance(print) | LCCN review 2018058007 purposes (ebook) only. | AllISBN rights reserved. 9781538101469This is (electronic) | ISBN 9781538101452 | ISBN 9781538101452 (cloth : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Black Arts movement—Encyclopedias. Classification: LCC NX512.3.A35 (ebook) | LCC NX512.3.A35 M58 2019 (print) | DDC 700.89/96073—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018053986 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. -

Biographical Description for the Historymakers® Video Oral History with Wadsworth A

Biographical Description for The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History with Wadsworth A. Jarrell, Sr. PERSON Wadsworth, Jarrell, 1929- Alternative Names: Wadsworth A. Jarrell, Sr.; Wadsworth Jarrell Life Dates: November 20, 1929- Place of Birth: Albany, Georgia, USA Residence: Cleveland, OH Occupations: Painter Biographical Note Revolutionary social artist Wadsworth A. Jarrell, Sr. was born in Albany, Georgia, in 1929, the youngest of six children. Jarrell credits his father, a furniture maker, and the rest of his family for supporting his childhood interest in art. After high school, Jarrell enlisted in the army, served in Korea, and then moved to Chicago. In 1954, Jarrell enrolled in the School of to Chicago. In 1954, Jarrell enrolled in the School of the Art Institute of Chicago majoring in advertising art and graphic design. Not long afterward, Jarrell lost interest in commercial art and took more drawing and painting classes. Graduating from the Art Institute in 1958, Jarrell spent several years working as a commercial artist. By the early 1960s, Jarrell was exhibiting his work widely throughout the Midwest. Meanwhile, the explosive social atmosphere of the era left him wanting to create art that was pertinent to the social movements of the day, the Civil Rights Movement and black liberation struggle. Jarrell joined the Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC), a group that created Chicago's Wall of Respect mural, a seminal piece in the 1960s urban mural movement. It was there that he met his future wife, Elaine Annette (Jae) Johnson, a clothing designer. With the eventual breakup of the Artists' Workshop of OBAC, Jarrell and fellow artists Jeff Donaldson and Barbara Jones-Hogu, among others, formed a collective called COBRA-Coalition of Black Revolutionary Artists, which later became AFRI-COBRA, the African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists. -

Africobra and the Negotiation of Visual Afrocentrisms Pratiques Artistiques

Pratiques artistiques et esthétiques afrocentristes Africobra and the Negotiation of Visual Afrocentrisms Kirstin L. ELLSWORTH Résumé : A la fin des années 1960, Africobra, un groupe d’artistes africains-américains basé à Chicago, développa un art expérimental qui mêlait des formes africaines et africaines-américaines avec des représentations d’une diaspora africaine. Africobra mit en place un programme artistique dans le cadre duquel l’art devait faire voir la beauté d’une culture noire universelle. Leur langage visuel devance la publication de l’ouvrage « Afrocentricity » de Molefi Asante, mais évoque pourtant déjà des tendances afrocentristes présentes tout au long de l’histoire culturelle africaine- américaine. Travaillant toujours aujourd’hui, Africobra souligne la valeur morale du processus de création pour l’artiste africain-américain travaillant dans un paradigme afrocentriste. Ce faisant, Africobra cherche à se réapproprier le pouvoir de définir ce que sont l’art et l’identité, ce qui avait été pendant des siècles aux Etats-Unis le privilège de la culture dominante. Mots-clés : Africobra, Afrocentrisme, Etats-Unis, art africain-américain. Abstract: In the 1960s, Africobra, a group of African-American artists in Chicago, experimented with art that synthesized African and African-American forms with interpretative visions of an African Diaspora. Africobra mandated a functional program for art-making in which art was to instruct in the beauty of a universal Black culture. Their imagery predates publication of Molefi Asante’s “Afrocentricity” yet negotiates in visual terms Afrocentric tendencies present throughout African American cultural historiography. Still working in the present day, Africobra emphasizes the moral value of the creative process for the individual African American artist within an Afrocentric paradigm. -

Alper Initiative for Washington Art It Takes a Nation

ALPER INITIATIVE FOR WASHINGTON ART IT TAKES A NATION IT TAKES A NATION: ART FOR SOCIAL JUSTICE WITH EMORY DOUGLAS AND THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY, AFRICOBRA, AND CONTEMPORARY WASHINGTON ARTISTS September 6 – October 23, 2016 American University Museum at the Katzen Arts Center Washington, DC ALPER INITIATIVE FOR WASHINGTON ART FOREWORD This exhibition presents the American important work gave visual form to I am grateful to Sandy Bellamy for University Museum’s best efforts to the 10 points of the Black Panther undertaking the formidable and timely accomplish artistic objectives rarely ideology that, unfortunately, continue task of organizing this exhibition and found in the same space and time: to have relevance fifty years later: writing the catalog, and Asantewa the exhibition is a program of the freedom, employment, opposition Boakyewa for her curatorial assistance. Alper Initiative for Washington Art, so against economic exploitation and Most importantly, I am thankful for our charge is to offer the community marginalization, affordable housing, the artists in the exhibition who have a venue for the examination and quality education, free health care, raised their voices so powerfully and promotion of the accomplishments opposition to police brutality, eloquently: Akili Ron Anderson, Holly of artists in the greater Washington, opposition to wars of aggression, Bass, Graham Boyle, Wesley Clark, Jay DC region. And, as a grantee of the opposition to the prison industrial Coleman, Larry Cook, Tim Davis, Jeff CrossCurrents Foundation, we are also complex, and access to the necessities Donaldson, Emory Douglas, Shaunté committed to presenting an exhibition of life. Gates, Jennifer Gray, Jae Jarrell, with strong relevance to the issues Wadsworth Jarrell, Njena Surae Jarvis, facing voters in the 2016 national The exhibition title is taken from an Simmie Knox, James Phillips, Beverly elections. -

This Striking Exhibition Shows How Blac...Ontributed to the Black Power

SABO KPADE Oct. 31, 2017 09:10PM EST Lorraine O'Grady (b. 1934). "Art Is (Girlfriends Times Two)," 1983/2009. Courtesy of the artist and Alexander Gray Associates, New York. This Striking Exhibition Shows How Black Artists Contributed to the Black Power Movement A review of Tate Modern's 'Soul of a Nation'—an exhibition that is giving African American artists their long overdue recognition. Martin Puryear's Self will forever be a wonder. It is sculpted from wood with a rich black luster and is said to be hollow inside The temptation to touch and feel it was to resist. At a glance its shape is that of a thumb. Move one step to the left or right and its precise shape changes. Move another step and it changes again. The amorphous nature of Puryear's creation gives it fluidity in character and meaning. Is the "self" of the title referring to one's inner state as whole in form and colour but also constantly changing? Or is it a vision of "blackness" as a reality shared by multitudes no two of whom are the same in the same way no two viewpoints of the sculpture are the same? Or not. The ambiguity adds to the fascination and to what in total is a most exhilarating exhibition of works by African Americans by Tate Modern called Soul of a Nation. This is the first time a major survey of works by African American artists are shown in the UK and only covers 20 years from 1963, the year of the great March on Washington led by Dr. -

N'vest-Ing in the People: the Art of Jae Jarrell

Jae Jarrell N’Vest-ing in the People: The Art of Jae Jarrell by D. Denenge Duyst-Akpem 1977 dawned on a Nigeria brimming with AFRICOBRA (African Commune of promise, full with the spoils of Niger Bad Relevant Artists)—the Delta oil and national pride 17 years legendary collective established in post-independence. It was a time of 1968 on Chicago’s south side with afrobeat musical innovation, of the goal to uplift and celebrate cross-continental exchange, of Black community, culture, and vibrancy and possibility. A contin- self-determination.1 Jae describes gent of 250 artists and cultural the journey as a “traveling party,” a producers selected by artist Jeff veritable who’s who of famous Donaldson and the U.S. organizing Black artists, and recalls thinking, committee, traveled from New York “If the afterlife is like this, then to Lagos, Nigeria, on two planes that’ll be alright!” 2 chartered by the U.S. Department of Foreign Affairs, to participate in Imagine the moment. The outline of FESTAC ’77, the Second World West Africa appears on the distant Black and African Festival of Arts horizon. Excitement mounts as the and Culture. Among them were Jae densely inhabited shorelines and and Wadsworth Jarrell, two of sprawling metropolis of Lagos Donaldson’s fellow co-founders of (pronounced “ley” “goss”) come into view, and even in the air condi- co-founder and curator Gerald Arts6 held in Dakar, Senegal in singer and civil rights activist tioned plane, you can feel the trop- Williams reflected on the cultural 1966 hosted by visionary President Miriam Makeba lovingly known as ical rays as the plane inches closer and creative impact of partici- Léopold Sédar Senghor, FESTAC “Mama Africa,” the awe-inspiring to landing. -

At the Broad Gives Black Artists Their Due

'Soul of a Nation' at the Broad Gives Black Artists Their Due Carren Jao March 25, 2019 It almost disappears from view, but in one corner, sitting beside Faith Ringgold’s large painting of a bleeding American flag, sits a small photo printed on the wall. It’s a reproduction of Phillip Lindsay Mason’s “Deathmakers.” The painting of two skeletal policemen carrying the body of a slain Malcolm X depicts a dramatic scene that underlies the turbulence of the times. The actual artwork isn’t at the Broad. Why? Because, despite the curators’ best efforts, it could not be located. The missing artwork is a telltale sign of how much effort the curators, Mark Godfrey and Zoe Whitley of Tate Modern, undertook to pick up the tenuous threads that make up the history of African American art. It is only in recent years that African American artists working in previous decades have seen their works added to the collections of major institutions, even then it has only been a mere trickle. Perhaps this latest sweeping exhibition will help hasten the addition of this crucial voice in the American art history canon. Thankfully, the fate of Mason’s work does not hold true for the pieces in “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power 1963-1983,” on view at the Broad until September 1. Originated at the Tate Modern in London, the show presents the work of over 60 Black artists working during the height of the civil rights movement in the 60s and two decades hence. -

"Africobra: Message to the People" at MOCA

www.smartymagazine.com "AfriCOBRA: Message to the People" at MOCA by Lili Tisseyre #The highly symbolic aesthetics of Black Art was discovered during the "Soul of a Nation" exhibition at the Tate Modern in September 2017 and again this summer at the Brooklyn Museum. On the occasion of the 2018 edition of Miami Art Basel, the Museum of Contemporary Art North in Miami celebrates AfriCOBRA's 50th anniversary for "African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists" and presents "AfriCOBRA, Message to the People", a "revolutionary" exhibition by the collective created in 1968 in Chicago. This legendary group of black artists defined, from its foundation, the immediately identifiable modern and visual aesthetics of what would be called the Black Arts Movement in the mid 1960s and 1970s. AfriCOBRA was born out of a first collective, the OBAC, which acquired national fame in 1967 with the creation of a monumental fresco, the Wall of Respect, in the Bronzeville district of Chicago. AfriCOBRA claims to be the tool for using art to meet the social and cultural challenges affecting the African-American community. This huge mural "depicts the 'Black Heroes' as positive role models for identity, community formation and revolutionary action. AfriCOBRA frees itself from codes and uses painting, printmaking, textile design, clothing design, photography and sculpture. The group's artists couple them with abstract motifs to evoke African artistic traditions and with visual elements of luminous, luminous "Kool-Aid" colours. Thus, works created from portraits, found everyday objects, letters and pictures emerge. Thus created, these raw, emotional and festive images of black figures defined the social, economic and political conditions of the black people.