Eureka! Student Inventor Reader | Grade 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesson: Rube Goldberg and the Meaning of Machines Contributed By: Integrated Teaching and Learning Program, College of Engineering, University of Colorado Boulder

Lesson: Rube Goldberg and the Meaning of Machines Contributed by: Integrated Teaching and Learning Program, College of Engineering, University of Colorado Boulder Quick Look Grade Level: 8 (7-9) Time Required: 20 minutes Lesson Dependency : None Subject Areas: Physical Science Summary Simple and compound machines are designed to make work easier. When we encounter a machine that does not t this understanding, the so-called machine seems absurd. Through the cartoons of Rube Goldberg, students are engaged in critical thinking about the way his inventions make simple tasks even harder to complete. As the nal lesson in the simple machines unit, the study of Rube Goldberg machines can help students evaluate the importance and usefulness of the many machines in the world around them. This engineering curriculum meets Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS). Engineering Connection One engineering objective is to help people via technological advances. Many of these greater advances in technology can be seen in machines invented by engineers. Rube Goldberg went to school to be an engineer, and after graduating, he decided to become an artist. He drew cartoons of inventions that did simple things in very complicated ways. His inventions involved many complex systems of simple machines, all organized in logical sequences, to accomplish simple tasks. An important skill for engineers is to An example Rube Goldberg contraption. evaluate the design of machines for their genuine usefulness for their audiences. Often, the best design is the simplest design. Pre-Req Knowledge In order to understand compound machines, it is helpful if students are familiar with the six individual simple machines and their abilities to make work easier, as described in lessons 1-3 of this unit. -

Simple Machine Simple Machines

Simple Machine Simple Machines • Changes effort, displacement or direction and magnitude of a load • 6 simple machines – Lever – Incline plane – Wedge – Screw – Pulley – Wheel and Axle • Mechanical Advantage 퐸푓푓표푟푡 퐷푠푡푎푛푐푒 퐿표푎푑 퐿 – Ideal: IMA = = = Note: (Effort Distance•Effort) =(Load Distance•Load) or Ein=Eout 퐿표푎푑 퐷푠푡푎푛푐푒 퐼푑푒푎푙 퐸푓푓표푟푡 퐸퐼 퐿표푎푑 퐿 – Actual: AMA= = 퐴푐푡푢푎푙 퐸푓푓표푟푡 퐸퐴 • Efficiency how the effort is used to move the load – Losses due to friction or other irreversible actions 퐸푛푒푟푔푦 푢푠푒푑 퐴푀퐴 퐸퐼 – η= = = Note: (EA=EI-Loss) 퐸푛푒푟푔푦 푠푢푝푝푙푒푑 퐼푀퐴 퐸퐴 2/25/2016 MCVTS CMET 2 Lever • Levers magnify effort or displacement • Three classes of levers based on location of the fulcrum 150lb – Class 1 lever: Fulcrum between the Load and Effort Examples: See-Saw, Pry Bar, Balance Scale – Class 2 lever: Load between the Effort and Fulcrum Examples: Wheelbarrow, Nut Cracker – Class 3 Lever: Effort between Load and Fulcrum Examples: Elbow, Tweezers Effort η=0.9 푑퐸 퐿 • 퐼푀퐴퐿푒푣푒푟 = = 푑퐿 퐸퐼 퐿 푑 8 • 퐴푀퐴 = 푒 퐿푒푣푒푟 퐸 퐼푀퐴 = = = 2 퐴 푑퐿 4 퐴푀퐴퐿푒푣푒푟 퐸퐴 퐿 150 • η= = 퐸 = = = 75푙푏 퐼푀퐴퐿푒푣푒푟 퐸퐼 퐼 퐼푀퐴 2 퐴푀퐴 = η퐼푀퐴 = 0.9 ∙ 2 = 1.8 퐿 150 퐸 = = = 83.33푙푏 퐴 퐴푀퐴 1.8 2/25/2016 MCVTS CMET 3 Incline Plane • Decreases effort to move a load to a new height or vertical rise Vert. • Friction opposes motion up the ramp increasing Rise the effort required (h) 푠 1 • 퐼푀퐴 = = ℎ 푠푛휃 θ 퐸푛푒푟푔푦 푢푠푒푑 퐴푀퐴 퐸 • η= = = 퐼 퐸푛푒푟푔푦 푠푢푝푝푙푒푑 퐼푀퐴 퐸퐴 θ w Ex. An incline plane with 20°slope is used to move a ℎ 36 a) 푠 = = = 105.3 푖푛 50-lb load a vertical distance of 36 inches. -

12. Simple Machines

12. Simple Machines Observe and discuss. In the following pictures, certain devices are used to accomplish certain tasks more easily. Name the devices and discuss how they help. Such devices which are used to get more work done in less time and less effort are called machines. The nail cutter, the bottle opener, the wheel used to push the load shown in the picture are all machines. They have only one or two parts and a simple and easy structure. Such machines are called simple machines. Simple machines can be handled easily, and there are less chances of these machines breaking down or getting damaged. We use many such machines in our day-to-day life. Various kinds of Can you tell? Observe the machines shown in the following pictures. For what purposes are they used? Can you name some other machines of this kind? These machines have many parts which carry out many processes for completing a task. For this purpose, the parts are joined to one another. Therefore, these machines are called complex machines. Some of the parts of such complex machines are actually simple machines. The structure of complex machines is complicated. Various machines In our day-to-day life, we use simple or complex machines depending upon the task to be carried out and the time and efforts required to do it. An inclined plane A heavy drum is to be loaded onto a truck. Ravi chose the plank A while Hamid chose the plank B. Rahi did not use a plank at all. 1. Who would find the drum heaviest to load? 2. -

Chapter 8 Glossary

Technology: Engineering Our World © 2012 Chapter 8: Machines—Glossary friction. A force that acts like a brake on moving objects. gear. A rotating wheel-like object with teeth around its rim used to transmit force to other gears with matching teeth. hydraulics. The study and technology of the characteristics of liquids at rest and in motion. inclined plane. A simple machine in the form of a sloping surface or ramp, used to move a load from one level to another. lever. A simple machine that consists of a bar and fulcrum (pivot point). Levers are used to increase force or decrease the effort needed to move a load. linkage. A system of levers used to transmit motion. lubrication. The application of a smooth or slippery substance between two objects to reduce friction. machine. A device that does some kind of work by changing or transmitting energy. mechanical advantage. In a simple machine, the ability to move a large resistance by applying a small effort. mechanism. A way of changing one kind of effort into another kind of effort. moment. The turning force acting on a lever; effort times the distance of the effort from the fulcrum. pneumatics. The study and technology of the characteristics of gases. power. The rate at which work is done or the rate at which energy is converted from one form to another or transferred from one place to another. pressure. The effort applied to a given area; effort divided by area. pulley. A simple machine in the form of a wheel with a groove around its rim to accept a rope, chain, or belt; it is used to lift heavy objects. -

Chapter 8 Machines 227 Machines Finding the Meaning of Unknown Words Before You Read This Chapter, Skim Through It Briefly and Identify Any Words You Do Not Know

This sample chapter is for review purposes only. Copyright © The Goodheart-Willcox Co., Inc. All rights reserved. Chapter 8 Machines 227 Machines Finding the Meaning of Unknown Words Before you read this chapter, skim through it briefly and identify any words you do not know. Record these words using the Reading Target In this walk-behind lawn mower, graphic organizer at the end of the chapter. Then read the chapter 8 the gas tank is placed with the engine for a more carefully. Use the context of the sentence to try to determine what each unified appearance. word means. Record your guesses in the graphic organizer also. After you read the chapter, follow the instructions with the graphic organizer to confirm your guesses. friction pneumatics gear power hydraulics pressure Charles Harrison designs inclined plane pulley lever screw machines used around linkage torque the home lubrication velocity machine viscosity Charles “Chuck” Harrison is one the most productive and respected mechanical advantage wedge American industrial designers of his time. He has been involved in the mechanism wheel and axle design of more than 750 consumer products that have improved the moment work life of millions. Harrison helped design the portable hair dryer, toasters, Discussion stereos, lawn mowers, sewing machines, Have students name the machines they use every day that help them do work, make their lives safer, and help them enjoy their leisure time. Harrison designed this hedge trimmer with plastic and the see-through measuring cup. He worked on power tools, fondue pots, Career Connection parts to minimize its weight. Have students identify careers associated with the design and development of new machines. -

Deltasci Gr5-6 Simple Machines

Simple Machines CONTENTS Think About . What Makes Things Move? . 2 How Are Work and Energy Related? . 3 What Are Simple Machines? Inclined Plane . 4 Lever . 5 Wheel and Axle . 7 Pulley . 8 Wedge . 9 Screw . 9 What Are Compound Machines? . 10 People in Science Archimedes . 12 Lillian Gilbreth, Industrial Engineer . 13 Did You Know? Your Body Has Levers . 14 How a Roller Coaster Works . 15 Glossary . 16 © Delta Education LLC. All rights reserved. Glossary compound machine machine made motion change of position or place; of two or more simple machines movement distance how far something moves newton unit used to measure force efficiency amount of work a machine potential energy stored energy does compared to the amount of pulley kind of wheel with a groove energy put into using the machine for a rope or cable effort force applied to a simple resistance force exerted by something machine you are trying to move energy ability to do work screw simple machine that is an force a push or pull inclined plane wrapped around a rod friction force caused by one object simple machine machine with rubbing against another few or no moving parts that makes fulcrum point around which it easier to do work. The six types a lever pivots or turns of simple machines are the lever, pulley, wheel and axle, inclined gravity force that pulls objects plane, wedge, and screw. toward the center of Earth speed how far an object moves inclined plane simple machine in a certain amount of time that is a flat surface with one end higher than the other wedge simple machine that is a type of inclined plane with one inertia tendency of a moving or two sloping surfaces object to stay in motion or a resting object to stay still wheel and axle simple machine that consists of a large wheel fixed joule unit used to measure work to a smaller wheel or shaft called kinetic energy energy of motion the axle lever simple machine that is a rigid work result of a force moving bar that turns around a fixed point an object over a distance machine any tool that uses energy to make work easier © Delta Education LLC. -

A Machine with Few Or No Moving Parts. Simple Machines Make Work Easier

Simple Machine: A machine with few or no moving parts. Simple machines make work easier. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=grWIC9VsFY4 Pulley 1.There are six simple machines. They make it easier for us to do work. A wheel pulley is one of the six simple machines. A pulley is a wheel with a rope wrapped around it. The wheel has a groove around the edge to hold the rope in place. You can attach one end of the rope to a heavy object that you want to lift. You will pull on the other end of the rope to lift the heavy object. Pulleys make work easier by changing the direction of the force needed to do work. It is hard to lift a heavy object up into the air. It is easier to pull the same object down to the ground. This is because of the force of gravity. Gravity is the force that pulls objects down to the Earth. Gravity helps to make work easier when you use a pulley. You can also use more than one pulley at a time to make the work even easier. The weight will feel lighter with each pulley that you use. If you use two pulleys, it will feel like you are pulling one-half as much weight. If you use four pulleys, it will feel like you are pulling one-fourth as much weight! The weight will be easy to move, but you will have more rope to pull with each pulley that you add. You will pull twice as much rope with two pulleys. -

Unified Science Approach K-1.4, Proficiency Levels 13-21 and Semester Courses

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 079 056 SE 015 823 AUTHOR Oickle, Eileen M., Ed. TITLE Unified Science Approach K-1.4, Proficiency Levels 13-21 and Semester Courses. INSTITUTION Anne Arundel County Board of Education, Annapolis, Md. PUB DATE Sep 72 NOTE 132p. EDRS PRICE MF -$O.65 HC-$6.58 DESCRIPTORS Biological Sciences; Course Descriptions; *Curriculum Guides; *Educational Objectives; Elementary School Science; *Instructional Materials; Physical sciences; *Science Education; Secondary School Sci.once; *Unified Studies Programs IDENTIFIERS Unified Science ABSTRACT Presented is the third part of the K-12 unified science materials used in the public schools of Anne Arundel County, Maryland. Detailed descriptions are presented for the roles of students and teachers, purposes of bibliography, major concepts in unified science, processes of inquiry, scheme and model for scientific literacy, and program rationale, design, and strategies. Proficiency levels 13-21 are incorporated together with 75 proficiency level objectives. Each objective is analyzed into a number of educational objective statements. Tnree sequences of course learning are further provided for students after completion of the work of proficiency levels 1-21. Course names, rationale for course study, unit descriptions, and prerequistes are entered in the descriptive sheet of each course offering. The course content, partly selected from other science curriculum improvement projects, is related to the fields of physical sciences, chemistry, biological sciences, physics, geology, oceanography, zoology, environmental studies, geomorphology, and botany. Applications of scientific principles are stressed. Included are a list of elementary projects, kits, and materials and bibliographies of selected elementary, secondary, and professional readings. (CC) Unified Science Approach US DEPWTMENT OF HEALTH EDUCATION 0 NELF ARE K-12 YA TIONAL iNSTiTuTE OF FOuCt.t.ON . -

New and Complete Clock and Watchmakers' Manual

i 381 1 'fva, 1 II m^^P I I i1 mI Hg m I K9ffl us' BB KiKfu I • 1 AHnSnuS ^H . Hi 30 4 CLOCK AND WATCHMAKERS' MANUAL. NEW AND COMPLETE CLOCK AND WATCHMAKERS' MANUAL. COMPRISING DESCRIPTIONS OP THE VAKIOUS GEARINGS, ESCAPEMENTS, AND COMPENSATIONS NOW IN USE IN FRENCH, SWISS, AND ENGLISH CLOCKS AND WATCHES, PATENTS, TOOLS, ETC. WITH DIRECTIONS FOR CLEANING AND REPAIRING. :ttf) Numerous BBrtjjrab in^H, Compile from tf)* jFretuf). WITH AN APPENDIX CONTAINING A HISTORY OF CLOCK AND WATCHMAKING IN AMERICA. By M. L. BOOTH, TRANSLATOR OF THE MARBLE WORKERS' MANUAL, ETC, NEW YORK: JOHN "WILEY, 56 WALKER STREET. I860. fs \ Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1860, by JOHN WILEY, in the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the United States for the Southern District of New York. ifi ' ^ <\ £ i R. CRAIGHEAD, Stereoiyper and Elecirotyper, CCai'ton iSuiDQinc[t 81, 83, and 85 Centre Street. TO HENRY FITZ, ESQ., OP NEW YORK CITY, AS A TOKEN OF APPRECIATION OF HIS KINDLY INTEREST AND AID, GENERAL INDEX. PAGE Preface, ix Explanation of Plates, . xv Introduction, 1 Watches, 4 Balance Wheel or Verge and Crown Wheel, . • . 6 Common Seconds Hand, ........ 14 Breguet, 16 Independent Seconds Hand, 24 Repeating, 28 Alarm, 36 Clocks, 41 Regulators, 42 Ordinary Pendulum, 42 Striking Hours and Quarters, 43 Belfry, 48 Pusee, the, . 53 Barrel, the, . 62 Stop works, the, j . 63 Workmanship in General, .......... 65 Gearings, 67 Cycloid, the, . 68 Epicycloid, the, 69 Escapements, 74 Balance Wheel, *75 Cylinder or Horizontal, . .15 Duplex, .80 M. -

Simple Machines

Delta Science Reader SSimpleimple MachinesMachines Delta Science Readers are nonfiction student books that provide science background and support the experiences of hands-on activities. Every Delta Science Reader has three main sections: Think About . , People in Science, and Did You Know? Be sure to preview the reader Overview Chart on page 4, the reader itself, and the teaching suggestions on the following pages. This information will help you determine how to plan your schedule for reader selections and activity sessions. Reading for information is a key literacy skill. Use the following ideas as appropriate for your teaching style and the needs of your students. The After Reading section includes an assessment and writing links. VERVIEW Students will O discover the forces that make things move The Delta Science Reader Simple Machines and stop moving introduces students to the world of simple understand how work and energy are machines and the energy that makes them related and learn the formula for work. Students explore the six simple calculating work machines—the inclined plane, the lever, the wheel and axle, the pulley, the wedge, and identify the six simple machines and how the screw—and read about the difference they work between simple and compound machines. examine nonfiction text elements such The book also presents biographical as table of contents, headings, lists, and sketches of two key scientists in this field— glossary Archimedes, an ancient Greek mathematician, and Lillian Gilbreth, a twentieth-century extend their reading by writing about the inventor. Students also investigate the levers ways that simple machines affect their lives in the human body and find out how a roller interpret photographs and diagrams to coaster works. -

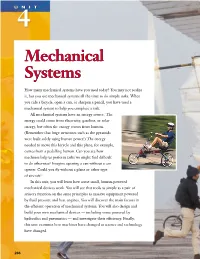

Mechanical Systems

UNIT Mechanical Systems How many mechanical systems have you used today? You may not realize it, but you use mechanical systems all the time to do simple tasks. When you ride a bicycle, open a can, or sharpen a pencil, you have used a mechanical system to help you complete a task. All mechanical systems have an energy source. The energy could come from electricity, gasoline, or solar energy, but often the energy comes from humans. (Remember that huge structures such as the pyramids were built solely using human power!) The energy needed to move this bicycle and this plane, for example, comes from a pedalling human. Can you see how machines help us perform tasks we might find difficult to do otherwise? Imagine opening a can without a can opener. Could you fly without a plane or other type of aircraft? In this unit, you will learn how some small, human-powered mechanical devices work. You will see that tools as simple as a pair of scissors function on the same principles as massive equipment powered by fluid pressure and heat engines. You will discover the main factors in the efficient operation of mechanical systems. You will also design and build your own mechanical devices — including some powered by hydraulics and pneumatics — and investigate their efficiency. Finally, this unit examines how machines have changed as science and technology have changed. 266 Unit Contents TOPIC 1 Levers and Inclined Planes 270 TOPIC 2 The Wheel and Axle,Gears, and Pulleys 285 TOPIC 3 Energy, Friction, and Efficiency 296 TOPIC 4 Force, Pressure, and Area 304 TOPIC 5 Hydraulics and Pneumatics 313 TOPIC 6 Combining Systems 326 TOPIC 7 Machines Throughout History 332 TOPIC 8 People and Machines 342 UNIT 4 • How do we use How many machines have you used today? machines to do work and How do we use mechanical devices such as to transfer energy? levers and pulleys to help us perform tasks? In Topics 1–3, you will learn about lots of How can we design and • mechanical devices. -

Simple Machines

© Faculty of Education, Monash University & Victorian Department of Education and Training Simple Machines Critical teaching ideas - Science Continuum F to 10 Level: Moving towards level 8 Student everyday experiences The modern world is rich with examples of complex machines whose workings are seldom understood. Students (and many adults) commonly use the word ‘machine’ to describe complex mechanical devices powered by an engine or electric motor and designed to perform useful labour saving tasks. Students often believe that all machines produce much more work than their human operators put in. This view is consistent with their experiences of most powered mechanical devices e.g. chainsaws, electric power tools and hydraulic excavators. Students’ everyday experiences seldom acknowledge devices like levers, inclined planes, wedges and pulleys as being types of ‘simple machines’. Although most students will have common experiences of the use of simple machines like levers and pulleys, few will have any understanding of why their design may provide an advantage or how they should be best employed. Many students also have difficulty in identifying or explaining these experiences to others and rarely identify parts of the human body, such as the arms or legs, as composed of levers. Research: Hapkiewicz (1992), Bryan, Laroder, Tippins, Emaz & Fox (2008), Meyer (1995), Norbury (2006) Scientific view The word machine has origins in both the Greek and Roman languages. The Greek word ‘machos’ means ‘expedient’ or something that ‘makes work easy’. The Romans have a similar understanding of the word ‘machina’ which means ‘trick’ or ‘device’. The basic purpose for which most simple machines are designed is to reduce the effort (force) required to perform a simple task.