Ganga-Flow : the Riverine and Overland Routes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Ganga River Basin Authority (Ngrba)

NATIONAL GANGA RIVER BASIN AUTHORITY (NGRBA) Public Disclosure Authorized (Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India) Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) Public Disclosure Authorized Volume I - Environmental and Social Analysis March 2011 Prepared by Public Disclosure Authorized The Energy and Resources Institute New Delhi i Table of Contents Executive Summary List of Tables ............................................................................................................... iv Chapter 1 National Ganga River Basin Project ....................................................... 6 1.1 Introduction .................................................................................................. 6 1.2 Ganga Clean up Initiatives ........................................................................... 6 1.3 The Ganga River Basin Project.................................................................... 7 1.4 Project Components ..................................................................................... 8 1.4.1.1 Objective ...................................................................................................... 8 1.4.1.2 Sub Component A: NGRBA Operationalization & Program Management 9 1.4.1.3 Sub component B: Technical Assistance for ULB Service Provider .......... 9 1.4.1.4 Sub-component C: Technical Assistance for Environmental Regulator ... 10 1.4.2.1 Objective ................................................................................................... -

List of Ph.D. Awarded

Geography Dept. B.H.U.: List of PhD awarded, 1958-2013 1 Updated: 19 August 2013: The 67th Geography Foundation Day B.H.U. Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, UP 221005. INDIA Department of Geography Doctoral Dissertation, Ph.D., in Geography: 1958 – 2013. No. Name of Scholar Title of the Doctoral Dissertation Awarded, & pub. year 1 2 3 4 1. Supervisor : Prof. Ram Lochan Singh (1946-1977) (late) 1. Shanti Lal Kayastha Himalayan Beas-Basin : A Study in Habitat, Economy 1958 and Society Pub. 1964 2. Radhika Narayan Ground Water Hydrology of Meerut District, U.P 1960 Mathur (earlier worked under Prof. Raj Nath, Geology Dept.) Pub. 1969 3. M. N. Nigam Urban Geography of Lucknow : (Submitted at Agra 1960 University) 4. S. L. Duggal Land Utilization Pattern in Moradabad District 1962 (submitted at Punjab University) 5. Vijay Ram Singh Land Utilization in the Neighbourhood of Mirzapur, U.P. 1962 Pub. 1970 6. Jagdish Singh Transport Geography of South Bihar 1962 Pub. 1964 7. Baccha Prasad Rao Vishakhapatanam : A Study in Geography of Port Town 1962 Pub. 1971 8. (Ms) Surinder Pannu Agro-Industrial Relationship in Saryupar Plain of U.P. 1962 9. Kashi N. Singh Rural Markets and Rurban Centres in Eastern U.P. 1963 10. Basant Singh Land Utilization in Chakia Tahsil, Varanasi 1963 11. Ram Briksha Singh Geography of Transport in U.P. 1963 Pub. 1966 12. S. P. Singh Bhagalpur : A Study in Regional Geography 1964 13. N. D. Bhattacharya Murshidabad : A Study in Settlement Geography 1965 14. Attur Ramesh TamiInadu Deccan: A Study. in Urban Geography 1965 15. -

M^Ittt of ^Fiuoitoplip M GEOGRAPHY

IMPACT OF AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTIVITY ON TIffi LEVEL OF REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT IN BIHAR DISSERTATION SUBMlTTtO IN PARTIAL rUtFILMiMT OF TNf MiOUtflEMENTS ton TNi AWAMO OP THi OMRif 01' M^ittt of ^fiUoitoplip m GEOGRAPHY BY TARIQ MAHMOOD USMAN! Under the Suptrvislon of Dr. SHAMSUL HAQUE SIDDIQlil DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITy AUGARH (INDIA) 1994 DS2545 ACKN0WLEDGEME^3TS I bow in gratitude to the Almighty "ALLAH" who enabled me to achieve this target, I feel great pleasure to express my deep sense of gratitude to my supeirvisor Dr. Shamsul Hague Siddiqui, Lecturer in the department of Geography, Aligarh Muslim University, for his valuable guidance at every stage in the preparation of this dissertation. I am also indebted to professor K.Z. Amani, Chairman of the department of Geography for his encouragement and for providing all the necessary facilities in the department. I must acknowledge my parents who have patiently borne the brunt of financing me through out my academic pursuit. But for their love, constant inspiration and blessing, I siftiply could not have continued my studies. I wish to thank to Shamim and Najmuddin , Librarian, for providing all relevant literature at the seminar library and to Sharmaji for typing the dissertation. Lastly, I express my thanks to Yasmeen, Afshan Khan, Shah id Imam, Atiqur Rehman, Habibur Rehman, Shariq and Anzar Khan who helped me all throughout the way for pre paring my disrertation. ( TARIQ MAHMOOD USMANI ) CONTENTS Page No. Acknowledgements ... i List of maps ... ii Introduction ... iii Ciiapters 1 General Geographical Charac- 1 teristics of study area ... 11 Conceptual Framework of Agri cultural productivity and Regional Development .. -

Malda Division

MALDA DIVISION 0 MALDA DIVISION 1 DISCLAIMER The information provided in this document is for the purpose of general guidance. Although all efforts have been made to ensure that it is authentic and accurate, however, in case of any conflict, the GR & SR /Accident Manual and other Codes would override. 2 3 4 CONTENTS Chapter Subject Matter Page No. Maps – Malda Division System Map 3 Rail & Road Map 4 1. ASSISTANCE FROM DEFENCE ORGANISATION IN CASE OF 6 RAILWAY DISASTER Assistance for Helicopter from Defence during Major Railway Disaters. 7 National Disaster Response Force (NDRF) 8-11 2. Important Numbers of Head Quarter & all Divisions of ER 13 Telephone numbers of Way side station of Malda division Telephone Numbers of Services HQs and Corresponding Railway Zonal/Divisional HQ. 3. CUG Numbers of Malda Division CUG Numbers of DRM, Accounts, Commercial CUG Numbers of Engineering & Electrical Department CUG Numbers of Mechanical department CUG Numbers of Medical department CUG Numbers of Operating, Personnel & RRB department CUG Numbers of S & T department CUG Numbers of Safety, Security & Stores department Phone Numbers of Medical/SBG & JMP Civil officers and Police offices 4. Station-wise information regarding disaster-management plan of Malda Division MLDT-BDAG L/C section DGLE-MPLR section BHW-SLJ ( Incl. TPH-RJL) section SBG-SBO section BGP-RPUR ( Incl. BGP-MDLE) section JMP-DNRE section Station-wise information regarding disaster-management plan of Malda Division 5 MLDT-BDAG L/C section DGLE-MPLR section BHW-SLJ ( Incl. TPH-RJL) section SBG-SBO section BGP-RPUR ( Incl. BGP-MDLE) section JMP-DNRE section 5 Chapter-1 ASSISTANCE FROM DEFENCE ORGANISATION IN CASE OF RAILWAY DISASTER. -

Sahebganj Districts, Jharkhand

कᴂद्रीय भूमि जल बो셍ड जल संसाधन, नदी विकास और गंगा संरक्षण विभाग, जल शक्ति मंत्रालय भारत सरकार Central Ground Water Board Department of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation, Ministry of Jal Shakti Government of India AQUIFER MAPPING AND MANAGEMENT OF GROUND WATER RESOURCES SAHEBGANJ DISTRICTS, JHARKHAND राज्य एकक कायाालय, रांची State Unit Office, Ranchi भारत सरकार Government of India जऱ स車साधन, नदी विकास एि車 ग車गा स車रक्षण म車त्राऱय Ministry of Water Resources, River Development & Ganga Rejuvenation केन्द्रीय भमू म-जऱ र्बो셍ा Central Ground Water Board PART – I/ भाग -१ Aquifer Maps and Ground Water Management Plan of Sahebganj district, Jharkhand जऱभतृ न啍शे तथा भूजऱ प्रबंधन योजना साहिबगंज जजऱा, झारख赍ड State Unit Office, Ranchi Mid-Eastern Region, Patna March 2019 रा煍य एकक कायााऱय रा車ची मध्य-ऩर्बू ी क्षेत्र ऩटना माचा २०१९ Aquifer Maps and Ground Water Management Plan of Sahebganj district, Jharkhand जऱभतृ न啍शे तथा भूजऱ प्रबंधन योजना साहिबगंज जजऱा, झारख赍ड State Unit Office, Ranchi Mid-Eastern Region, Patna March 2019 रा煍य एकक कायााऱय रा車ची मध्य-ऩर्बू ी क्षेत्र ऩटना माचा २०१९ REPORT ON AQUIFER MAPPING AND MANAGEMENT PLAN (PART – I) OF SAHEBGANJ DISTRICT, JHARKHAND 2017 – 18 CONTRIBUTORS’ Principal Authors Sunil Toppo : Junior Hydrogeologist (Scientist-B) Supervision & Guidance A.K.Agrawal : Regional Director G. K. Roy : Officer-In- Charge T.B.N. Singh : Scientist-D Dr Sudhanshu Shekhar : Scientist-D Hydrogeology, GIS maps and Management Plan Sunil Toppo : Junior Hydrogeologist Dr Anukaran Kujur : Assistant Hydrogeologist Atul Beck : Assistant Hydrogeologist Hydrogeological Data Acquisition and Groundwater Exploration Sunil Toppo : Junior Hydrogeologist Dr Anukaran Kujur : Assistant Hydrogeologist Atul Beck : Assistant Hydrogeologist Geophysics : B. -

Dharmasvamin OCR.Pdf

BIOGRAPH'\"" OF DHARl\'lASV AMIN ( Chag lo t;,,'1-ba Chos-rje-dpal) A TIBETAN MONK PILGRIM ORIGINAL TIBETAN TEXT decipheredand translated by Dr. GEORGE ROERICH, ~M.A., Ph.D., PllOFBSIOR AND THB HE.AD Of THE DEPARTMENT OP rlULOSOPHY, INSTITUTE OF ORIENTAL STUDIES, THE ACADAMY OP SCIENCES, MOSCOW, IJ, S, ~. R, With a historical and critical Iutro,luction By Dr. A. S. ALTEKAR Director K. P.JAYASWAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE K. P. JAVASWAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE PATNA 11159. ] PUBl.lSIIED ON BEHALF OP THE KASH! PRASAD JA YASWAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE, PATNA DY ITS DIRECTOR, DR, A, S. ALTEKAR, M.A., Ll .. B.,D,LITT. All rights resm·ed PRINTED IN INUIA BY SIIANTILAL JAIN AT SHRI JAINENDRA l'R~:ss, JAWAHARNAOAR, DELHI, INTJIA. 1. The Government ofBihar established the K. P. Jayaswal Research Institute at Patna in 195 r with the object, inter-alia, to promote historical research, archaeological excavations and investigations and publication of works of permanent value to scholars. This Institute is one of the five others established by this Government as a token of their homage to the traditition of learning and scholarship for which ancient Bihar was noted. Apart from the J ayaswal Research Institute, five others have been established to give incentive to research and advancement of knowledge, the Nalanda Institute of Research and Post-Graduate Studies in Buddhist Learning and Pali at Nalanda, the Mithilll: Institute of Research and Post• Graduate Studies in Sanskrit Learning at Darbhanga, the Bihar Rashtra Bhasha Parishad for Research and advanced Studies in Hindi at Patna, the Institute of Post-Graduate Studies and Research in Jain and Prakrit Learning at Vaishali and the Institute of Post-Graduate Studies and Research in Arabic and Persian Leaming in Patna. -

![Ftyk Fuokzpu Dk;Kzy;] Lkgscxat](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2720/ftyk-fuokzpu-dk-kzy-lkgscxat-1372720.webp)

Ftyk Fuokzpu Dk;Kzy;] Lkgscxat

ftyk fuokZpu dk;kZy;] lkgscxat ch0,y0vks0 dh lwph 01& jktegy fo/kku lHkk fuokZpu {ks= AC- Booth Booth Name Name of BLO Mobile No Address NO Number Middle School Hajipur Diyara 1-Vill- Hajipur Diyara, Dist- 1 1 Savita Devi 9939967486 (New Building) Sahibganj Middle School Hajipur Diyara, 2-Vill- Hajipur Diyara, Dist- 1 2 Sangita Devi 9955137519 (Old Building) Sahibganj Middle School Hajipur Diyara, 3-Vill- Hajipur Diyara, Dist- 1 3 Sulekha Devi 7739650069 (Old Building) Sahibganj 4-Vill- Hajipur Bhitta, Dist- 1 4 Up. Middle School, Rajgaown Ramakanta Devi 8936016787 Sahibganj 5-Vill- Hajipur Bhitta, Dist- 1 5 Up. Middle School, Rajgaown Babita Devi 9973195910 Sahibganj 1 6 Panchayat Building, Dihari Manju Kumari 9973195910 6-Vill- Dihari, Dist- Sahibganj 1 7 Up.High School,, Dihari Ajay Kumar Yadav 7766017485 7-Vill- Dihari, Dist- Sahibganj Up. Middle School, Patwar 8-Vill- Patwar Tola, Dist- 1 8 Rita Devi 9801340228 Tola Sahibganj Up. Middle School, Patwar 1 9 Usha Devi 9661205005 9-Vill- Dihari, Dist- Sahibganj Tola Up. Middle School Badi 10-Vill-Bholiya Tola, Dist- 1 10 Shavya Devi 8409462362 Kodarjanna Sahibganj Middle School Badi 11-Vill-Bari Kojarjanna South, 1 11 Renu Devi 9006958107 Kodarjanna (South Part) Dist- Sahibganj Middle School Badi 12-Vill-Mahaldar Tola, Dist- 1 12 Shrimani Devi 8271720579 Kodarjanna (North Part) Sahibganj Middle School Badi 13-Vill- Naya Tola, Dist- 1 13 Kiran Devi 9771823375 Kodarjanna (North Part) Sahibganj Urdu Middle School 14-Vill- Makhmalpur South, 1 14 Akhtari Begam 9801430040 Makhmalpur Dist- Sahibganj Panchayat Building 15-Vill-Rahamat Tola, Dist- 1 15 Anjuman Aara 7295915866 Makhmalpur ( South Part) Sahibganj Panchayat Building 16-Vill- Sarpanch Tola, Dist- 1 16 Alimuddin Jang 9798190712 Makhmalpur ( South Part) Sahibganj Up. -

ATDC -16-17.Xlsx

List of Skilled Candidates for Skill Development Training Programme on Sewing Machine Operator (B+ A) Sponsored By NSFDC in Session 2016-17 ( From 15.09.16 to 14.12.16 ) Address Status of Training Stipend Name of the Annual S.no Father's Name Category Area Disbursement Candidate Income Amount DELHI B-423,Gali no-3 Meet Nager,Gokalpuri,Delhi-110094 1 Rekha Rani Sri Ram SC Urban 72000/- 3000 Completed B-118,G.no-3,Saboli Khadda,Delhi-110093 2 Priyanka Jagdish SC Urban 48000/- 3000 Completed H.no-739,G.no-13 Mandoli Vistar,nand nagri Delhi-110093 3 Pushpa Panna Lal SC Urban 60000/- 3000 Completed H.no-E61-A247,D2 Block Jhuggi Nand Nagri Delhi-110093 4 Vandana Ramnath SC Urban 35000/- 4500 Completed E-56-22,G.T.Road Village Khera Delhi- 110095 5 Suman Heera Lal SC Rural 60000/- 4500 Completed H.no-13-737,Mandoli Vistar Mondoli Delhi-110093 6 Komal Satya Pal SC Urban 60000/- 3000 Completed B-3-197 Nand Nagri Delhi 110093 7 Gayatri Panna Lal SC Urban 48000/- 1500 Completed C-2-330,G.no-12 Harsh Vihar Delhi 110093 8 Jai Bharti Mitter Singh SC Urban 48000/- 1500 Completed D-2-287,Nand Nagri,Mondoli Delhi- 110093 9 Priyanka Kumari Bajrangi SC Urban 72000/- 1500 Completed E-60-400 Jhuggi,Sunder Nagri Delhi- 110093 10 Ragini Ashok SC Urban 25000/- 3000 Completed H.no-28,G.no-2,Mandoli Village Delhi- 110093 11 Jyoti Santer Pal SC Urban 60000/- 3000 Completed E-18-602,G.no-18 Amar Colony Gokal Pur Delhi110094 12 Laxmi Pooja Devender Singh SC Urban 80000/- 3000 Completed H.no-105,D.D.A Janta Flats G.T.B Enclave Dilshad Garden 13 Meena Kumari Ram Awadh -

List of Consumers of Sahibganj

SL. NO Consumer No. Consumer Name Consumer Address Tarrif Total Amount 298 GVCS000006 THE I/C MEDICAL OFFICER RANGA HOSPITAL, RANGA NDS-3 11,58,453 397 GVCS000046 DISTRICT HOMEGAURD COMMANDENT OFFICE, BANSKOLA,SAKRIGALI NDS-3 10,96,411 396 GVCS000029 B.D.O. , RAJMAHAL , NAYA BAZAR,RAJMAHAL NDS-3 10,90,657 395 GVCS000030 B D O , TALJHARI BLOCK NDS-3 10,88,846 297 MJPCS00557 BHARTI INFRATEL LTD PROP- A DWIVEDI, MIRZAPUR NDS-3 7,91,505 392 TPCS000005 DIVN.ELEC.EXEC.ENGINEER , E.RLY,MALDA,AT-TEENPAHAR NDS-3 6,98,808 198 LHDCS00001 SUNIL KR BHARTIYA S/o LT MURARILAL BHARTIYA, LOHANDA,AT-PETROL PUMP NDS-3 6,81,282 296 BHCS002471 ADIWASI KALYAN HOSTEL B S K COLLEGE, BARHARWA NDS-3 6,14,929 386 GVCS000002 SUPDT OF POLICE , RAJMAHAL THANA NDS-3 6,11,735 385 GVCS000033 CIVIL S.D.O. , S.D.O. COURT,RAJMAHAL NDS-3 6,11,126 295 GVCS000015 THE B.D.O. , PATHNA BLOCK,PATHNA NDS-3 5,93,452 294 GVCS000014 THE PRAKHAND BIKASH OFFI. , BARHARWA BLOCK NDS-3 5,90,543 380 GVCS000004 THANA INCHARGE , RADHANAGAR THANA,UDHWA NDS-3 5,14,026 191 MZCCS00783 BRANCH MANAGER STATE BANK OF INDIA, MIRZA CHAUKI NDS-3 4,79,984 190 MDSCS00045 BRANCH MANAGER STATE BANK OF INDIA, CHHOTA MADANSAHI NDS-3 4,63,921 188 BROCS00546 HEAD MASTER STR GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL, BANDARKOLA,BORIO,SAHIBGAN NDS-3 4,56,278 377 GVCS000007 MEDICAL OFFICER , REFERAL HOSPITAL,RAJMAHAL NDS-3 4,32,801 179 GVCS000009 DIST EMPLOYMENT OFFICE , LOHANDA NDS-3 3,98,842 373 GVCS000001 SUPDT OF JAIL , RAJMAHAL NDS-3 3,75,802 369 RJLCS01800 ATC TOWER OF INDIA (P) LT C/o MD ZIAUDDIN AHMED, GUDRAGHAT,RAJMAHAL NDS-3 -

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHICAL JOURNAL of INDIA ISSN : 0027-9374/2018/1641-1663, Vol

1 NATIONAL GEOGRAPHICAL JOURNAL OF INDIA ISSN : 0027-9374/2018/1641-1663, Vol. 64, No. 1-2, March-June, 2018 Editor Prof. R. S. Yadava 1641 Reminiscences of Professor Shanti Lal Kayastha Anand Mohan and Arvind Mohan 1-6 1642 Shanti Lal Kayastha : A Humanist amongst Human Geographers Sarfaraz Alam 7-34 1643 Environmental Sustainability - Issues and Challenges in India H.S. Sharma 35-46 1644 Status of Biodiversity in West Bengal: Threat to Conservation and Scope of Restoration Ranjan Basu 47-63 1645 From Bonsai to Big Banyan: Scaling up Community Driven Green Livelihood Initiatives Sachin Kumar and Bhupinder S. Marh 64-75 1646 Disaster, Displacement and Rehabilitation: A Case Study of Kosi Floods in North Bihar Sneh Gangwar and Baleshwar Thakur 76-92 1647 Landslide Hazard Zonation in and around Litan Village along NH-202, Ukhrul District, Manipur, India M. Okendro and R.A.S. Kushwaha 93-103 1648 Resource Use and Conservation of Kabartal Wetland Ecosystem, Bihar S.C. Rai and Mukesh Kumar 104-110 1649 Women and Natural Resource Management Swati Sucharita Nanda 111-117 1650 Estimation of Soil loss Sensitivity in the Jinari River Basin using the Universal Soil Loss Equation Nilotpal Kalita, Akangsha Borgohain, Dhrubajyoti Sahariah 118-127 and Siddhinath Sarma 1651 Deteriorating Scenario of Lakes: A Case Study of Ramgarh Lake, India Alka Singh and V.N. Sharma 128-143 2 1652 Rural Environmental Characteristics: A Case Study of the Selected Central Himalayan Villages R.C. Joshi and Masoom Reza 144-154 1653 Ecology and Economy of Home Gardens in a Village Environment of the Brahmaputra Valley, Assam Nityananda Deka and A.K.Bhagabati 155-165 1654 Perspectives on Urban Climate Change and Policy Measures in India Salahuddin Qureshi 166-173 1655 Failing Cityscape: Urbanization and Urban Climate Bikramaditya K. -

Environment Monitoring Plan of Sahibganj Terminal for Construction and Operation Phase

“CAPACITY AUGMENTATION OF NATIONAL WATERWAY.1” (Jal Marg Vikas Project) ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT REPORTS VOLUME - 5: Environmental Management Plan (EMP) for Sahibganj Terminal May 2016 Consolidated Environmental Impact Assessment Report of National Waterways-1, Volume-5 Table of Contents 1.1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 3 1.2. Brief On Sahibganj Terminal ........................................................................................... 3 1.3. Description of Environment ............................................................................................. 4 1.4. Environmental Management and Monitoring Plan.......................................................... 8 1.5. Environment Health and Safety Cell ............................................................................... 9 1.6. Reporting Requirements: ................................................................................................ 9 List of Tables Table 1.1 : Salient Environmental Features of Sahibganj Terminal Site ............................................. 5 Table 1.2 : Environment Management Plan Sahibganj Terminal During Construction Phase ......... 10 Table 1.3 2 Consolidated Environmental Impact Assessment Report of National Waterways-1, Volume-5 Chapter 1. EMP FOR SAHIBGANJ TERMINAL 1.1. Introduction Inland waterways Authority of India (IWAI) has proposed to augment the navigation capacity of waterway NW-1 (Haldia to Allahabad) -

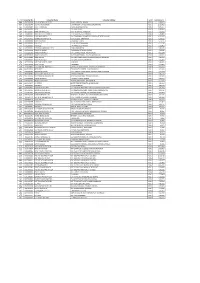

BC-1) Ds Vh;Kfzfkz;Ksa Dh Izkjafhkd Es?Kk Lwpha Categore-OBC-1 Merit List Intermediate / Matric Graduation PG/Other ITI Grand Total Total Sl

dk;kZy; mi fodkl vk;qDr&lg&ftyk dk;ZØe leUo;d] ikdqM+ fiåoxZå (BC-1) ds vH;kfZFkZ;ksa dh izkjafHkd es?kk lwphA Categore-OBC-1 Merit List Intermediate / Matric Graduation PG/Other ITI Grand Total Total Sl. Form Father/Husband Score Name of Candidate Permanent Address Present Address Date of Birth (Column Remarks Male/ No. No. name Femal (Colum 13+17+21 Mobile Mobile No. Hons Total Total n 22/3) Marks Marks Marks Marks ) Percentage Percentage Percentage SC/ ST/ OBC/Gen ST/ SC/ Age as on 01.01.2016 PGDRD/PGDBR 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 (19- 22 23 24 25 20) Vill-Khidirpur, Post- Vill-Khidirpur, Post- Dinanath Kumar Jalu Prasad 1 8 Devpur, PS-Hiranpur, Devpur, PS-Hiranpur, 12.08.1990 27 M OBC-I 263 311 62.20 636 79.50 5 84.50 1071 66.94 66.94 213.64 71.21 Mondal Mandal Dist-Pakur, 816107 Dist-Pakur, 816107 9693882196 Matric Vill-Budhbachouk, Post- Vill-Budhbachouk, Post- Marksheet 2 193 MD Manzar Alam MD Sanaulla 21.11.1984 33 M OBC-I 618 68.67 519 64.88 5 69.88 591 73.88 73.88 212.42 70.81 Malmandro, Dist-Godda Malmandro, Dist-Godda not Attached 8809657574 other dist Vill-Islampur, Post- Vill-Islampur, Post- 3 201 Abdur Rajjak MD Arsad Ali Bhawanipur, PS- Bhawanipur, PS- 18.04.1990 27 M OBC-I 558 361 72.20 538 67.25 5 72.25 1354 67.70 67.70 212.15 70.72 Pakur(M), Dist-Pakur Pakur(M), Dist-Pakur 7679675759 Vill-Dhoria, PO- Vill-Simal Duma, PO- Dipendra Kumar Radhe Shyam B.ed 4 285 Guhiajori, PS-Dumka, Guhiajori, PS-Jama, Dist- 20.06.1986 31 M OBC-I 301 650 92.86 419 52.38 5 57.38 968 60.50 60.50 210.73 70.24 Bhandari Bhandari Other Dist.