Public Confidence in Transit June 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Corporate Report GC2.Doc APPENDIX 1

Clerk’s Files Corporate Originator’s CD.15.SRR Files Report DATE: June 1, 2015 TO: Chair and Members of General Committee Meeting Date: June 17, 2015 FROM: Edward R. Sajecki Commissioner of Planning and Building SUBJECT: Funding Request for SRRA Research on the Impact of RER and SmartTrack on Office Development in Mississauga RECOMMENDATION: That a funding request by Strategic Regional Research Alliance (SRRA) of $50,000 to support research, as described in the report titled “Funding Request for SRRA Research on the Impact of RER and SmartTrack on Office Development in Mississauga” from the Commissioner of Planning & Building, dated June 1, 2015, be approved. REPORT HIGHLIGHTS: • The province has made a commitment to deliver Regional Express Rail (RER) which will expand GO Transit rail service to include 15- minute two-way, all-day GO Transit rail service. • The RER initiative for the Lakeshore, Milton and Kitchener GO Transit rail corridors is one of the City’s priority transit projects. • The proposed SmartTrack plan builds on the RER initiative, with 53-kilometre, all-day, two-way frequent train service including a new heavy rail spur line along Eglinton Avenue West to Mississauga’s Airport Corporate Centre. CD.15.SRR General Committee - 2 - June 1, 2015 • Strategic Regional Research Alliance (SRRA) is undertaking research to provide forecasts of office development and employment growth likely to result from RER and SmartTrack. These forecasts will provide input for ridership modeling of SmartTrack/RER. • This research is valuable given the importance of Office development for the success of the City’s future employment growth. -

COUNCIL INFORMATION PACKAGE September 15, 2017 Table Of

COUNCIL INFORMATION PACKAGE September 15, 2017 Table of Contents Item From Subject Page 1 Denise Beard, Manager of Patrick J McNally Foundation 1 Community Development Donation Rob Axiak, Manager of File: 155-03-12 Recreation Services 2 Vito Tolone, Director of Ontario Municipal Commuter Cycling 2-3 Transportation Services Program File: 155-03-20 3 Andrea Smith, Manager of City Wide Population and Built-Up 4-10 Policy & Research, Planning Area Residential Unit Growth Analysis and Building Department (September, 2017) File: 155-03-10 4 Metrolinx Metrolinx Board Meeting – September 11-13 2017 File: 770-10-1 5 Forests Ontario Ontario’s Green Leaf Challenge 14-16 File: 145-01 6 Halton Hills Council Resolution regarding violence 17 in Charlottesville, Virginia 160-01 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Metrolinx Board Meeting - September 2017 The Metrolinx Board of Directors met today to receive a number of reports, including updates on PRESTO, Metrolinx’s capital projects, the next Regional Transportation Plan (RTP) and fare integration. Board Chair Rob Prichard addressed his correspondence with Minister Del Duca on the proposed Kirby Road and Lawrence East GO stations, which confirms that Metrolinx will not enter into any obligations or agreements unless and until management and the Board are satisfied these stations are justified, and that the Minister will respect and support whatever conclusion the Board reaches. The Next RTP: Draft Plan for Public Consultation Chief Planning Officer Leslie Woo presented the staff recommended version of the Draft 2041 RTP. With the new Draft RTP Metrolinx is aiming to go beyond what was in The Big Move to put traveller needs at the core of planning and operations. -

The One Toronto Transit Plan the One Toronto Transit Plan

THE ONE TORONTO TRANSIT PLAN THE ONE TORONTO TRANSIT PLAN As Mayor, John Tory will make Toronto more liveable, affordable and functional. Public transit is at the heart of what it takes to improve Toronto in each of these areas. John Tory’s One Toronto Transit Plan is a collection of initiatives and public transit investments that will get our city moving in seven years, and provide relief to the Yonge-University-Spadina subway line. THE ONE TORONTO PLAN WILL: • Start construction of the Scarborough subway extension immediately. • Engage the City with the Government of Ontario’s and Metrolinx’s plans for Regional Express Rail (RER) – all-day, two-way surface subway service on existing GO track lines with new higher-speed vehicles . • Start with the SmartTrack line as the first RER project, providing 53 km of relief. The SmartTrack line will run from the Airport Corporate Centre in the west, down to Union Station and back up to Markham in the east, with 22 new station stops and four interchanges with the TTC rapid transit network. • Finance the City’s one third of the capital cost of the SmartTrack line without raising property taxes, using tax increment financing. • Provide new express bus services for a segment of travelers that can be moved much quicker if fewer stops are made en route. Examples, which have been discussed, include, Don Mills Road, Dufferin Street and Front Street/Liberty Village. THE ONE TORONTO TRANSIT PLAN BENEFITS ASSOCIATED WITH TORY’S ONE TORONTO TRANSIT RELIEF PLAN INCLUDE: • Bringing relief sooner, to more Torontonians, rather than just the downtown- concentrated proposals of other candidates. -

Smarttrack Ridership Analysis: Project Final Report

SMARTTRACK Research Report RIDERSHIP ANALYSIS Project Final Report Eric J. Miller, James Vaughan, Monika Nasterska June 2016 SMARTTRACK RIDERSHIP ANALYSIS PROJECT FINAL REPORT Prepared for the City Manager, City of Toronto by: Eric J. Miller, Ph.D. Professor, Department of Civil Engineering Director, Transportation Research Institute Research Director, Travel Modelling Group University of Toronto James Vaughan & Monika Nasterska Travel Modelling Group, University of Toronto Transportation Research Institute June, 2016 i Executive Summary Project Objectives On December 11, 2014, City Council directed the City Manager in consultation with the Province/Metrolinx to develop a work plan to undertake an accelerated review of the SmartTrack and RER plans. Council also directed the City Manager to retain the specialized services of the University of Toronto Transportation Research Institute (UTTRI) to support the planning analysis and required transit ridership modelling as a component of the overall review.1 On February 10, 2015, City Council considered the report EX2.2 SmartTrack Work Plan (2015- 2016), and approved the accelerated work plan for the review of SmartTrack.2 The UTTRI component of this work was to provide transit ridership estimates and other key network performance measures using the City’s new Regional Travel Demand Model (GTAModel Version 4.0) developed at the University of Toronto by UTTRI. As detailed in the final Terms of Reference for the UTTRI work, this work included: • Confirming the integrated RER and SmartTrack Service Concept to be modelled. • Completion and validation of a new travel demand model system to be used by the City of Toronto in this and similar studies of transit ridership and travel demand. -

Transportation Factsheet Overview

Transportation Factsheet Overview Whether it’s by car, bicycle, transit or walking, being able to move around easily is an important component of a healthy and dynamic city. Transportation has been identified as the most important issue by many Torontonians. This is likely because it’s becoming increasingly difficult to travel within and between cities in the region (Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area (GTHA)). There are a number of key issues affecting our region’s mobility. There has been a lack of transit infrastructure investment (streetcars, subways, light rail) from all levels of government over the past several decades; Development and growth within the suburbs means increased traffic congestion coming from all areas of the GTHA but there are difficulties in managing regional transportation Office space is scattered throughout the GTA and much of it is not located close to rapid transit, making commuting by transit difficult. (Think about offices and businesses at the Airport Corporate Centre in Mississauga – it’s very difficult to get there by transit); Generally our roads were built to accommodate cars. Cycling is becoming more popular, especially in urban centres like Toronto. However, cities in the GTHA have been slow to adapt and invest in cycling infrastructure; The suburbs that are throughout the GTA were made for the car, low density making servicing those areas by transit expensive. Transit affordability has been an ongoing concern for the City and with the recent increase in TTC fares, this is only going to get worse. Currently, every TTC rider pays the same adult, senior, student, or child fare, regardless of their ability to pay. -

Presentation 7:20 Questions of Clarification 7:30 Facilitated Open House 8:30 Adjourn

Waterfront Transit “Reset” Phase 2 Study Public Information & Consultation Meetings September 18 & 26, 2017 Agenda 6:00 Open House 6:30 Agenda Review, Opening Remarks and Introductions 6:40 Study Overview and Presentation 7:20 Questions of Clarification 7:30 Facilitated Open House 8:30 Adjourn 2 Project Study Team • A Partnership of: • The project study team is led by a joint City-TTC- Waterfront Toronto Executive Steering Committee • Metrolinx, City of Mississauga and MiWay have also provided input on relevant aspects of the study 3 What’s the Purpose of this Meeting? • Present the waterfront transit network travel demand considerations to 2041 • Present and gather feedback on options assessment for transit improvements in key areas of the network, including: – Union Station – Queens Quay Connection – Humber Bay Link – Bathurst - Fleet - Lake Shore – Queens Quay Intersection • Report the overall draft findings of the Phase 2 Study, priorities, and draft directions for further study prior to reporting to Executive Committee and Council 4 Study Timeline 5 Phase 1 Recap To view the Phase 1 Report and other background material, please visit the City’s website: www.toronto.ca/waterfronttransit 6 Vision Provide high quality transit that will integrate waterfront communities, jobs, and destinations and link the waterfront to the broader City and regional transportation network Objectives Connect waterfront communities locally and to Downtown with reliable and convenient transit service: • Promote and support residential and employment growth -

Eglinton Crosstown West Extension Initial Business Case February 2020

Eglinton Crosstown West Extension Initial Business Case February 2020 Eglinton Crosstown West Extension Initial Business Case February 2020 Contents Executive Summary 1 Scope 1 Method of Analysis 1 Findings 3 Strategic Case 3 Economic Case 3 Financial Case 4 Deliverability and Operations Case 4 Summary 4 Introduction 7 Background 8 Business Case Overview 10 Problem Statement 13 Case for Change 14 Problem Statement 14 Opportunity for Change 15 Key Drivers 16 Strategic Value 18 iv Investment Options 24 Introduction 25 Study Area 25 Options Development 25 Options for Analysis 27 Assumptions for Analysis and Travel Demand Modelling 33 Strategic Case 34 Introduction 35 Strategic Objective 1 – Connect More Places with Better Frequent Rapid Transit 38 Criterion 1: To provide high quality transit to more people in more places 38 Criterion 2: To address the connectivity gap between Eglinton Crosstown LRT and Transitway BRT 40 Strategic Objective 2 – Improve Transit’s Convenience and Attractiveness 42 Criterion 2: To provide more reliable, safe and enjoyable travel experience 42 Criterion 2: To boost transit use and attractiveness among local residents and workers 45 Strategic Objective 3 – Promote Healthier and More Sustainable Travel Behaviours 52 Criterion 1: To improve liveability through reduction in traffic delays, auto dependency and air pollution 52 Criterion 2: To encourage use of active modes to access stations 53 v Strategic Objective 4 – Encourage Transit-Supportive Development 57 Criterion 1: Compatibility with Existing Neighbourhood -

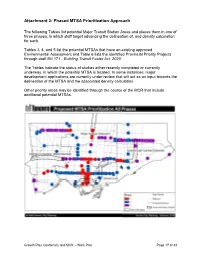

Attachment 2: Phased MTSA Prioritization Approach

Attachment 2: Phased MTSA Prioritization Approach The following Tables list potential Major Transit Station Areas and places them in one of three phases, in which staff target advancing the delineation of, and density calculation for each. Tables 3, 4, and 5 list the potential MTSAs that have an existing approved Environmental Assessment and Table 6 lists the identified Provincial Priority Projects through draft Bill 171 - Building Transit Faster Act, 2020. The Tables indicate the status of studies either recently completed or currently underway, in which the potential MTSA is located. In some instances, major development applications are currently under review that will act as an input towards the delineation of the MTSA and the associated density calculation. Other priority areas may be identified through the course of the MCR that include additional potential MTSAs. Growth Plan Conformity and MCR – Work Plan Page 17 of 33 Table 2: Proposed MTSA Prioritization Phase 1 Station Line Related Study Status Bathurst Line 2 - Bloor-Danforth Completed Bay Line 2 - Bloor-Danforth Completed Islington Line 2 - Bloor-Danforth Underway Kipling Line 2 - Bloor-Danforth Underway Sherbourne Line 2 - Bloor-Danforth Completed Line 2 - Bloor-Danforth /Line 1- Completed Bloor-Yonge Yonge-University Line 2 - Bloor-Danforth / Line 1- Completed Spadina Yonge-University Line 2 - Bloor-Danforth/ Line 1- Completed St George Yonge-University Avenue Eglinton Crosstown LRT Completed Birchmount Eglinton Crosstown LRT Underway Chaplin Eglinton Crosstown LRT Completed Eglinton Eglinton Crosstown LRT Completed Golden Mile Eglinton Crosstown LRT Underway Hakimi Lebovic Eglinton Crosstown LRT Underway Leaside Eglinton Crosstown LRT Completed Mount Pleasant Eglinton Crosstown LRT Completed O'Connor Eglinton Crosstown LRT Underway Pharmacy Eglinton Crosstown LRT Underway Sentinel Finch West LRT Completed Kipling GO - Milton Underway St. -

Relief Line South Environmental Project Report, Section 5 Existing and Future Conditions

Relief Line South Environmental Project Report Section 5 - Existing and Future Conditions The study area is unique in that it is served by most transit modes that make up the Greater 5 Existing and Future Conditions Toronto Area’s (GTA’s) transit network, including: The description of the existing and future environment within the study area is presented in this • TTC Subway – High-speed, high-capacity rapid transit serving both long distance and local section to establish an inventory of the baseline conditions against which the potential impacts travel. of the project are being considered as part of the Transit Project Assessment Process (TPAP). • TTC Streetcar – Low-speed surface routes operating on fixed rail in mixed traffic lanes (with Existing transportation, natural, social-economic, cultural, and utility conditions are outlined some exceptions), mostly serving shorter-distance trips into the downtown core and feeding within this section. More detailed findings for each of the disciplines have been documented in to / from the subway system. the corresponding memoranda provided in the appendices. • TTC Conventional Bus – Low-speed surface routes operating in mixed traffic, mostly 5.1 Transportation serving local travel and feeding subway and GO stations. • TTC Express Bus – Higher-speed surface routes with less-frequent stops operating in An inventory of the existing local and regional transit, vehicular, cycling and pedestrian mixed traffic on high-capacity arterial roads, connecting neighbourhoods with poor access transportation networks in the study area is outlined below. to rapid transit to downtown. 5.1.1 Existing Transit Network • GO Rail - Interregional rapid transit primarily serving long-distance commuter travel to the downtown core (converging at Union Station). -

Help Plan Transit in Toronto

HELP PLAN TRANSIT IN TORONTO The City of Toronto, TTC and Metrolinx are working Please join us at a Public Information Session to learn together to bring more transit to communities across more about network transit planning and the projects the city with connections to the entire Greater that will transform the way you move around Toronto Toronto and Hamilton Region. and beyond. THE PROJECTS – FOUR MAJOR TRANSIT STUDIES ARE INTERRELATED Network analysis by Metrolinx Network analysis by the City of Toronto and TTC 1. GO Regional Express Rail (RER) 2. SmartTrack 3. Scarborough Subway Extension 4. Relief Line These projects have a positive impact on the overall transit network: • Improving the network by creating connections between future projects and existing lines. • Coordinating regional and local priorities. PUBLIC INFORMATION SESSIONS (venues are accessible) The following four sessions will provide an overview of the four major transit studies listed above. Saturday June 13 Wednesday June 17 Saturday June 20 Monday June 22 Etobicoke North York Downtown Scarborough Burnhamthorpe Spring Garden Hyatt Regency Hotel Winston Churchill Collegiate Institute Baptist Church Regency Ballroom Collegiate Institute 500 The East Mall 112 Spring Garden Ave 370 King Street West 2239 Lawrence Ave East 9:30 am – 12:30 pm 6:30 pm – 9:00 pm 9:30 am – 12:30 pm 6:30 pm – 9:00 pm The following four sessions will focus on specific projects as noted. Monday June 15 Thursday June 18 Wednesday June 24 Thursday June 25 Relief Line SmartTrack Scarborough Subway Relief Line Estonian House Archbishop Romero Extension Riverdale Collegiate 958 Broadview Ave Catholic Secondary School Scarborough Civic Centre Institute 6:30 pm – 9:00 pm 99 Humber Blvd. -

Smarttrack Status Update

ACTION REQUIRED ____________________________________________________________________________ Subject: SmartTrack Status Update Date: October 28, 2015 At its meeting on October 20, 2015, the City of Toronto Executive Committee adopted EX9.1: SmartTrack Status Update, and in doing so, requested that the report be forwarded for information to the Toronto Transit Commission, the Ministry of Transportation, Metrolinx, the City of Mississauga and York Region. http://app.toronto.ca/tmmis/viewAgendaItemHistory.do?item=2015.EX9.1 It is recommended that the TTC Board: 1. receive the foregoing for information. Original signed by Vincent Rodo Chief Financial & Administration Officer 1-11 Attachment: EX9.1 – SmartTrack Status Update Peter Wallace MT0101m City Manager City Hall Tel: 416-392-3551 100 Queen Street West Fax: 416-392-1827 1 East Tower, 11 h Floor [email protected] Toronto, Ontario MSH 2N2 www.toronto.ca October 26, 2015 Andy Byford Chief Executive Officer Toronto Transit Commission 1900 Yonge Street Toronto, ON M4S 122 Dear Mr. Byford, Re: SmartTrack Status Update Report At the October 20, 2015 Executive Committee meeting, Executive Committee requested the City Manager to forward the SmartTrack Status Update report for information to the Toronto Transit Commission, the Ministry. of Transportation, Metrolinx, the City of Mississauga and York Region. The full report, EX9. 1 SmartTrack Status Update is enclosed for your reference, and can also be found at the following link: http://app.toronto.ca/tmmis/viewAgenda1temHistory.do?item=2015.EX9.1 City staff have been working closely with the TIC, Metrolinx, and the Province, to implement the accelerated work plan that was approved at the February 10, 2015 meeting of Toronto City Council. -

Smarttrack Ridership Analysis

SMARTTRACK RIDERSHIP ANALYSIS PROJECT FINAL REPORT Prepared for the City Manager, City of Toronto by: Eric J. Miller, Ph.D. Professor, Department of Civil Engineering Director, Transportation Research Institute Research Director, Travel Modelling Group University of Toronto James Vaughan & Monika Nasterska Travel Modelling Group, University of Toronto Transportation Research Institute June, 2016 i Executive Summary Project Objectives On December 11, 2014, City Council directed the City Manager in consultation with the Province/Metrolinx to develop a work plan to undertake an accelerated review of the SmartTrack and RER plans. Council also directed the City Manager to retain the specialized services of the University of Toronto Transportation Research Institute (UTTRI) to support the planning analysis and required transit ridership modelling as a component of the overall review.1 On February 10, 2015, City Council considered the report EX2.2 SmartTrack Work Plan (2015- 2016), and approved the accelerated work plan for the review of SmartTrack.2 The UTTRI component of this work was to provide transit ridership estimates and other key network performance measures using the City’s new Regional Travel Demand Model (GTAModel Version 4.0) developed at the University of Toronto by UTTRI. As detailed in the final Terms of Reference for the UTTRI work, this work included: • Confirming the integrated RER and SmartTrack Service Concept to be modelled. • Completion and validation of a new travel demand model system to be used by the City of Toronto in this and similar studies of transit ridership and travel demand. • Development and review of forecasting assumptions that provide key inputs into the transit ridership forecasts.