The Kill Team

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joker (2019 Film) - Wikipedia

Joker (2019 film) - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joker_(2019_film) Joker (2019 film) Joker is a 2019 American psychological thriller film directed by Todd Joker Phillips, who co-wrote the screenplay with Scott Silver. The film, based on DC Comics characters, stars Joaquin Phoenix as the Joker. An origin story set in 1981, the film follows Arthur Fleck, a failed stand-up comedian who turns to a life of crime and chaos in Gotham City. Robert De Niro, Zazie Beetz, Frances Conroy, Brett Cullen, Glenn Fleshler, Bill Camp, Shea Whigham, and Marc Maron appear in supporting roles. Joker was produced by Warner Bros. Pictures, DC Films, and Joint Effort in association with Bron Creative and Village Roadshow Pictures, and distributed by Warner Bros. Phillips conceived Joker in 2016 and wrote the script with Silver throughout 2017. The two were inspired by 1970s character studies and the films of Martin Scorsese, who was initially attached to the project as a producer. The graphic novel Batman: The Killing Joke (1988) was the basis for the premise, but Phillips and Silver otherwise did not look to specific comics for inspiration. Phoenix became attached in February 2018 and was cast that July, while the majority of the cast signed on by August. Theatrical release poster Principal photography took place in New York City, Jersey City, and Newark, from September to December 2018. It is the first live-action Directed by Todd Phillips theatrical Batman film to receive an R-rating from the Motion Picture Produced by Todd Phillips Association of America, due to its violent and disturbing content. -

01:00:01 GFX Center Nickelodeon the Naked Brothers Band . 01:00

SHOW: (Job Name) Version: (Tape ID) PRODUCER: (Client Name) TIMECODE VISUALS AUDIO 01:00:01 GFX Center . Nickelodeon The Naked Brothers Band 01:00:03 Alex dancing around room and Alex <singing>: Milk is fun. It’s sippy and peppy. singing. Yip, yip, yippy. Drink milk and be a wild, happy guy like me. Whee hee! Hi. This is the song the milk Alex sitting on couch talking to people want me to sing so I can advertise my new I camera. Love Milk clothing line. I sing this song so people will remember to drink milk and while they’re drinking milk, they’ll remember to wear my clothes. Mm. But I don’t think the song captures 01:00:30 Alex takes drink of milk from the loveliness of the milk. Milk isn’t peppy or yippy; carton. milk is cozy as golden light. And they grow it from the fresh red and white cartons. But the clothes are awesome though, red, white and blue, do-rag, my colors. And check it out, a cow on the logo. Moo. And each has a bubble. Milk is a warm puppy, milk is my best friend, milk makes my 01:01:00 Alex points to various clothing tummy feel warm and cozy, milk is the bomb. And items. look, Alex Wolff socks tied just the way I like ‘em. Oh yeah, baby. Nat enters room, sits on couch and Nat: Alex where have you been? We need to talks to Alex. rehearse. Alex: Can’t you see I’m in the middle of important business? Nat: You’re eight. -

Applause Magazine, Applause Building, 68 Long Acre, London WC2E 9JQ

1 GENE WIL Laughing all the way to the 23rd Making a difference LONDON'S THEATRE CRITI Are they going soft? PIUS SAVE £££ on your theatre tickets ,~~ 1~~EGm~ Gf1ll~ G~rick ~he ~ ~ e,London f F~[[ IIC~[I with ever~ full price ticket purchased ~t £23.50 Phone 0171-312 1991 9 771364 763009 Editor's Letter 'ThFl rul )U -; lmalid' was a phrase coined by the playwright and humourl:'t G eorge S. Kaufman to describe the ailing but always ~t:"o lh e m Broadway Theatre in the late 1930' s . " \\ . ;t" )ur ul\'n 'fabulous invalid' - the West End - seems in danger of 'e:' .m :: Lw er from lack of nourishmem, let' s hope that, like Broadway - presently in re . \ ,'1 'n - it too is resilient enough to make a comple te recovery and confound the r .: i " \\' ho accuse it of being an en vironmenta lly no-go area whose theatrical x ;'lrJ io n" refuse to stretch beyond tired reviva ls and boulevard bon-bons. I i, clUite true that the season just past has hardly been a vintage one. And while there is no question that the subsidised sector attracts new plays that, =5 'ears ago would a lmost certainly have found their way o nto Shaftes bury Avenue, l ere is, I am convinced, enough vitality and ingenuity left amo ng London's main -s tream producers to confirm that reports of the West End's te rminal dec line ;:m: greatly exaggerated. I have been a profeSSi onal reviewer long enough to appreciate the cyclical nature of the business. -

2010 16Th Annual SAG AWARDS

CATEGORIA CINEMA Melhor ator JEFF BRIDGES / Bad Blake - "CRAZY HEART" (Fox Searchlight Pictures) GEORGE CLOONEY / Ryan Bingham - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) COLIN FIRTH / George Falconer - "A SINGLE MAN" (The Weinstein Company) MORGAN FREEMAN / Nelson Mandela - "INVICTUS" (Warner Bros. Pictures) JEREMY RENNER / Staff Sgt. William James - "THE HURT LOCKER" (Summit Entertainment) Melhor atriz SANDRA BULLOCK / Leigh Anne Tuohy - "THE BLIND SIDE" (Warner Bros. Pictures) HELEN MIRREN / Sofya - "THE LAST STATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) CAREY MULLIGAN / Jenny - "AN EDUCATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) GABOUREY SIDIBE / Precious - "PRECIOUS: BASED ON THE NOVEL ‘PUSH’ BY SAPPHIRE" (Lionsgate) MERYL STREEP / Julia Child - "JULIE & JULIA" (Columbia Pictures) Melhor ator coadjuvante MATT DAMON / Francois Pienaar - "INVICTUS" (Warner Bros. Pictures) WOODY HARRELSON / Captain Tony Stone - "THE MESSENGER" (Oscilloscope Laboratories) CHRISTOPHER PLUMMER / Tolstoy - "THE LAST STATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) STANLEY TUCCI / George Harvey – “UM OLHAR NO PARAÍSO” ("THE LOVELY BONES") (Paramount Pictures) CHRISTOPH WALTZ / Col. Hans Landa – “BASTARDOS INGLÓRIOS” ("INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS") (The Weinstein Company/Universal Pictures) Melhor atriz coadjuvante PENÉLOPE CRUZ / Carla - "NINE" (The Weinstein Company) VERA FARMIGA / Alex Goran - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) ANNA KENDRICK / Natalie Keener - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) DIANE KRUGER / Bridget Von Hammersmark – “BASTARDOS INGLÓRIOS” ("INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS") (The Weinstein Company/Universal Pictures) MO’NIQUE / Mary - "PRECIOUS: BASED ON THE NOVEL ‘PUSH’ BY SAPPHIRE" (Lionsgate) Melhor elenco AN EDUCATION (Sony Pictures Classics) DOMINIC COOPER / Danny ALFRED MOLINA / Jack CAREY MULLIGAN / Jenny ROSAMUND PIKE / Helen PETER SARSGAARD / David EMMA THOMPSON / Headmistress OLIVIA WILLIAMS / Miss Stubbs THE HURT LOCKER (Summit Entertainment) CHRISTIAN CAMARGO / Col. John Cambridge BRIAN GERAGHTY / Specialist Owen Eldridge EVANGELINE LILLY / Connie James ANTHONY MACKIE / Sgt. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

Certain Women

CERTAIN WOMEN Starring Laura Dern Kristen Stewart Michelle Williams James Le Gros Jared Harris Lily Gladstone Rene Auberjonois Written, Directed, and Edited by Kelly Reichardt Produced by Neil Kopp, Vincent Savino, Anish Savjani Executive Producers Todd Haynes, Larry Fessenden, Christopher Carroll, Nathan Kelly Contact: Falco Ink CERTAIN WOMEN Cast (in order of appearance) Laura LAURA DERN Ryan JAMES Le GROS Fuller JARED HARRIS Sheriff Rowles JOHN GETZ Gina MICHELLE WILLIAMS Guthrie SARA RODIER Albert RENE AUBERJONOIS The Rancher LILY GLADSTONE Elizabeth Travis KRISTEN STEWART Production Writer / Director / Editor KELLY REICHARDT Based on stories by MAILE MELOY Producers NEIL KOPP VINCENT SAVINO ANISH SAVJANI Executive Producers TODD HAYNES LARRY FESSENDEN CHRISTOPHER CARROLL NATHAN KELLY Director of Photography CHRISTOPHER BLAUVELT Production Designer ANTHONY GASPARRO Costume Designer APRIL NAPIER Casting MARK BENNETT GAYLE KELLER Music Composer JEFF GRACE CERTAIN WOMEN Synopsis It’s the off-season in Livingston, Montana, where lawyer Laura Wells (LAURA DERN), called away from a tryst with her married lover, finds herself defending a local laborer named Fuller (JARED HARRIS). Fuller was a victim of a workplace accident, and his ongoing medical issues have led him to hire Laura to see if she can reopen his case. He’s stubborn and won’t listen to Laura’s advice – though he seems to heed it when the same counsel comes from a male colleague. Thinking he has no other option, Fuller decides to take a security guard hostage in order to get his demands met. Laura must act as intermediary and exchange herself for the hostage, trying to convince Fuller to give himself up. -

Embargoed Until Announced at the Ceremony on Sunday 14 February 2016

EMBARGOED UNTIL ANNOUNCED AT THE CEREMONY ON SUNDAY 14 FEBRUARY 2016 JOHN BOYEGA WINS THE EE RISING STAR AWARD AT THE EE BRITISH ACADEMY FILM AWARDS IN 2016 The Star Wars actor tops the public vote The EE Rising Star Award is the only one at the EE British Academy Film Awards to be voted for by the public The other 2016 nominees were: Taron Egerton, Brie Larson, Dakota Johnson and Bel Powley Last year’s EE Rising Star Award winner, Jack O’Connell presented this year’s award Previous winners include Will Poulter, Tom Hardy, Kristen Stewart, Noel Clarke, Eva Green and James McAvoy London, Sunday 14 February 2016: EE is proud to announce John Boyega as the winner of the EE Rising Star Award in 2016. The EE Rising Star Award is the only publicly-voted award presented at the EE British Academy Film Awards, and a hotly contested accolade for up and coming acting talent. Boyega was one of five international actors nominated for their exceptional talent and recognised as a true star in the making. The other nominees were: Taron Egerton, Brie Larson, Dakota Johnson and Bel Powley. JOHN BOYEGA was cast as the lead role in Star Wars: Episode VII – The Force Awakens, which premiered at the end of last year. Boyega had his screen debut in the critically acclaimed BBC series, Becoming Human, where he starred as Danny Curtis the school bully in four episodes. His first foray into feature films was playing the lead in cult sci-fi film, Attack the Block, which opened SXSW in 2011, collecting a plethora of international awards. -

NSF Programme Book 23/04/2019 12:31 Page 1

two weeks of world-class music newbury spring festival 11–25 may 2019 £5 2019-NSF book.qxp_NSF programme book 23/04/2019 12:31 Page 1 A Royal Welcome HRH The Duke of Kent KG Last year was very special for the Newbury Spring Festival as we marked the fortieth anniversary of the Festival. But following this anniversary there is some sad news, with the recent passing of our President, Jeanie, Countess of Carnarvon. Her energy, commitment and enthusiasm from the outset and throughout the evolution of the Festival have been fundamental to its success. The Duchess of Kent and I have seen the Festival grow from humble beginnings to an internationally renowned arts festival, having faced and overcome many obstacles along the way. Jeanie, Countess of Carnarvon, can be justly proud of the Festival’s achievements. Her legacy must surely be a Festival that continues to flourish as we embark on the next forty years. www.newburyspringfestival.org.uk 1 2019-NSF book.qxp_NSF programme book 23/04/2019 12:31 Page 2 Jeanie, Countess of Carnarvon MBE Founder and President 1935 - 2019 2 box office 0845 5218 218 2019-NSF book.qxp_NSF programme book 23/04/2019 12:31 Page 3 The Festival’s founder and president, Jeanie Countess of Carnarvon was a great and much loved lady who we will always remember for her inspirational support of Newbury Spring Festival and her gentle and gracious presence at so many events over the years. Her son Lord Carnarvon pays tribute to her with the following words. My darling mother’s lifelong interest in the arts and music started in her childhood in the USA. -

Annual Report on Giving

PROFESSIONAL CHILDREN'S SCHOOL ANNUAL REPORT ON GIVING 2017–2018 132 West 60th Street HEAD OF SCHOOL New York, NY 10023 James Dawson pcs-nyc.org LIFE TRUSTEES Professional Children's School Charlotte M. Ford is a vibrant independent school Ernest H. Frank that provides a rigorous college- Peter P. Nitze preparatory education in a supportive environment for 2017–2018 BOARD OF TRUSTEES young people pursuing careers Eileen Mulry Dieck, Chair or pre-professional training in the Diane Kenney, Vice Chair performing arts, competitive sports, William Graham Jacobi, Treasurer + and other endeavors. Stephanie J. Hull, Secretary Michele Barakett ++ Donald B. Brant, Jr. Kristin Kennedy Clark Amy Crate * Pierce Cravens * Rachel Curry * James Dawson Joyce Giuffra Michael Gleicher * Melanie Harris * Nina v. K. Levent + John B. Murray Erica Marks Panush Susan Gluck Pappajohn * Raushan Sapar INSTITUTIONAL ADVANCEMENT COMMITTEE Amy Crate * Pierce Cravens * Rachel Curry * James Dawson Eileen Mulry Dieck Joyce Giuffra Michael Gleicher * Erica Marks Panush Susan Gluck Pappajohn * Raushan Sapar * Alumni + Board Term Ended in May 2018 ++ Board Term Began in May 2018 aspect of individuals within a shared space, but the deeper understanding of FROM HEAD OF SCHOOL community, per the dictionary, that draws on “the feeling of fellowship with others, DR. as a result of sharing common attitudes, interests and goals”. It is a collective JAMES sense of empowerment, a unified belief in dreams, a tribute to passion and interest, DAWSON an affirmation of remarkable young -

Los Nominados a La 24Ta Edición De Los Premios Del Sindicato De Actores De Cine Han Sido Anunciados

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Rosalind Jarrett Sepulveda [email protected] (424) 309-1400 Los nominados a la 24ta edición de los Premios del Sindicato de Actores de Cine han sido anunciados. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- La ceremonia se transmitirá en vivo el domingo 21 de enero de 2017, en TNT y TBS a las 8pm (ET) 5pm (PT). LOS ÁNGELES (13 de diciembre de 2017) – Los nominados a la 24ta edición de los Premios del Sindicato de Actores de Cine por sus excepcionales actuaciones individuales y como elenco en cine y televisión en 2017, así como los nominados por sus excepcionales actuaciones como elencos de dobles de acción en cine y televisión fueron anunciados esta mañana en el SilverScreen Theater del Pacific Design Center en West Hollywood. La Presidenta de SAG-AFTRA, Gabrielle Carteris, presentó a Olivia Munn (X-Men Apocalypse, The Predator) y Niecy Nash (Claws, The Soul Man), quienes anunciaron los nominados para los Premios de este año, a transmitirse en vivo a través de TNT, TBS, truTV, sagawards.tntdrama.com, truTV.com y sagawards.org, en las aplicaciones móviles de TNT y TBS, y los canales en redes sociales de TNT y TBS en Facebook, Twitter y YouTube. Poco antes, la presidenta del Comité de los Premios SAG, JoBeth Williams, y la miembro del Comité, Elizabeth McLaughlin, anunciaron a los nominados como elencos de dobles de acción durante una transmisión en línea, en vivo a través de tntdrama.com/sagawards y sagawards.org. Repeticiones de ambos anuncios están disponibles para su visualización en tntndrama.com/sagawards y sagawards.org. La lista completa de los nominados a la 24ta edición anual de los Premios del Sindicato de Actores de Cine se encuentra a continuación de este aviso. -

Varsity Issue

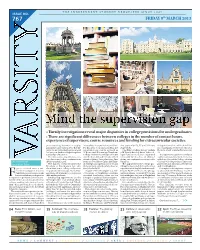

THE INDEPENDENT STUDENT NEWSPAPER SINCE 1947 ISSUE NO. th 767 FRIDAY 8 MARCH 2013 EV1122, DAVIDSIMMONS, TULANE PUBLIC RELATIONS TULANE PUBLIC EV1122, DAVIDSIMMONS, ZABETHEASTCOBBER, TYTUP, LENSCAPBOB, TRINITY.CAM.AC.UK, INKL TRINITY.CAM.AC.UK, LENSCAPBOB, TYTUP, ZABETHEASTCOBBER, MindO CREDITS, CLOCKWISE FROM ind the supervisionsuper gap PHOTO CREDITS, CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: 303STAINLESSSTEEL, ELI 303STAINLESSSTEEL, LEFT: TOP CREDITS, CLOCKWISE FROM PHOTO • Varsity investigations reveal major disparities in college provisions for undergraduates • There are significant differences between colleges in the number of contact hours, experience of supervisors, course resources and funding for extracurricular societies peers studying elsewhere - despite inequalities in supervision provision. rst years with 53, 55 and 59 hours of supervision time, while their Trin- paying the same tuition fees. e dif- For rst year economics students the respectively. ity counterparts received 43. ose at ferences are particularly pronounced supervision gap can be as much as One King’s College history student Homerton had 38 and at Roinson only for rst year students beginning their 71 hours, with the average Newnham told Varsity that they knew “other col- 33. Cambridge educations. College student receiving 115 hours leges have more classes organised e supervision gap for second year e data covers supervisions, col- over the year, but only 43 hours if they internally by directors of studies”, mathematicians was up to 33 hours, lege classes and college seminars from attended Sidney Sussex last year. First giving one explanation for the wide with Lucy Cavendish College o ering byPHELIM BRADY the last academic year. years at Gonville & Caius and Trin- variation. 62 hours of college contact time com- Deputy News Editor The figures, released under the ity College saw supervisors for 89 and e gap between the college pro- pared with just 28 hours at Homerton Freedom of Information Act, also 66 hours respectively, while those at viding the most and the least hours of and 30 at Magdalene. -

PH Love Simon Final.Pdf

1 FOX 2000 PICTURES präsentiert EINE TEMPLE HILL Produktion NICK ROBINSON JOSH DUHAMEL und JENNIFER GARNER Executive Music Producer JACK ANTONOFF Music Supervisor SEASON KENT Musik ROB SIMONSEN Kostümdesign ERIC DAMAN Co-Produzent CHRIS McEWEN Schnitt HARRY JIERJIAN Bühnenbild AARON OSBORNE Director of Photography JOHN GULESERIAN Executive Producer TIMOTHY M. BOURNE 2 Produzenten WYCK GODFREY MARTY BOWEN POUYA SHAHBAZIAN ISAAC KLAUSNER Basierend auf dem Roman “Simon vs. the Homo Sapiens Agenda” von BECKY ALBERTALLI Drehbuch ELIZABETH BERGER & ISAAC APTAKER Regie GREG BERLANTI Filmlänge: 110 Minuten Kinostart: 28. Juni 2018 3 SYNOPSIS Jeder verdient eine großartige Liebesgeschichte. Für den siebzehnjährigen Simon Spier ist es allerdings etwas komplizierter: er muss seiner Familie und seinen Freunden erst noch erklären, dass er schwul ist. Und er muss auch noch herausfinden, wer der anonyme Mitschüler ist, in den er sich online verliebt hat. Die Lösung beider Probleme nimmt einen urkomischen aber auch beunruhigenden Verlauf und verändert Simons Leben vollkommen. Regisseur Greg Berlanti (Ausführender Produzent u.a. bei „Everwood”, „The Flash” und „Riverdale”) inszenierte LOVE, SIMON nach einem Drehbuch von Elizabeth Berger und Isaac Aptaker. Es basiert auf Becky Albertallis vielgelobten Roman und erzählt eine ebenso komische wie aufrichtige Geschichte übers Erwachsenwerden und von der aufregenden Erfahrung zu sich selbst zu finden und sich zu verlieben. DAS BUCH LOVE, SIMON ist eine Adaption von Becky Albertallis Jugendbuch „Nur drei Worte – Love, Simon”. Nach seinem Erscheinen im Januar 2012 gewann das Buch den William C. Morris Award für das Beste Jugendbuch-Debüt des Jahres und wurde in die Long-List für den National Book Award aufgenommen. Albertalli hätte sich nie träumen lassen, dass ihr Buch veröffentlicht wird, geschweige denn, dass es sich zu einem preisgekrönten Bestseller entwickelt und nun von einem der großen Filmstudios verfilmt wird: „Ich arbeitete als Psychologin, als ich das Buch schrieb”, erzählt sie.