Exeter College Oxford

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Living with New Developments in Jericho and Walton Manor

LIVING WITH NEW DEVELOPMENTS IN JERICHO AND WALTON MANOR A discussion paper examining the likely impacts upon the neighbourhood of forthcoming and expected developments Paul Cullen – November 2010 1. Introduction 2. Developments approved or planned 3. Likely effects of the developments 3.1 More people living in the area. 3.2 More people visiting the area daily 3.3 Effects of construction 4. Likely outcomes of more residents and more visitors 4.1 More activity in the neighbourhood every day 4.2 More demand for shops, eating, drinking and entertainment 4.3 More vehicles making deliveries and servicing visits to the area 4.4 More local parking demand 4.5 Demand for places at local schools will grow 5. Present day problems in the neighbourhood 5.1 The night-time economy – and litter 5.2 Transient resident population 5.3 Motor traffic congestion and air pollution 5.4 Narrow and obstructed footways 6. Wider issues of travel and access 6.1 Lack of bus links between the rail station and Woodstock Road 6.2 Lack of a convenient pedestrian/cycle link to the rail station and West End 6.3 The need for travel behaviour change 7. The need for a planning led response 7.1 Developer Contributions 7.2 How should developers contribute? 7.3 What are the emerging questions? 8. Next steps – a dialogue between the community, planners and developers 1 LIVING WITH NEW DEVELOPMENTS IN JERICHO AND WALTON MANOR A discussion paper examining the likely impacts upon the neighbourhood of forthcoming and expected developments 1. Introduction Many new developments are planned or proposed in or near Jericho and these will have a substantial impact on the local community. -

Develop Your Workforce Employer’S Guide to Higher Education This Booklet Sets out to Explain How Higher Level Skills Can Benefit Your Business

Develop your workforce Employer’s Guide to Higher Education This booklet sets out to explain how higher level skills can benefit your business. We’ll show how you, your business and workforce can benefit from work-based higher education and the various levels and types of qualification available. We’ll direct you to where you can access higher education near you and provide other useful contact addresses. What are higher level skills? “High level skills – the skills associated with higher education – are good for the individuals who acquire them and good for the economy. They help individuals unlock their talent and aspire to change their life for the better. They help businesses and public services to innovate and prosper. They help towns and cities thrive by creating jobs, helping businesses become more competitive and driving economic regeneration. High level skills add value for all of us.” Foreword, Minister of State for Lifelong Learning, Further and Higher Education ‘Higher Education at Work – High Skills: High Value’, DIUS, April 2008 Why? There are good reasons why you should consider supporting your workforce to achieve qualifications which formally recognise their skills and why those skills will improve your business opportunities: • you will be equipped with the skills needed to meet current and future challenges in line with your business needs • new ideas and business solutions can be generated by assigning employees key project work as part of their course based assignments • your commitment to staff development will increase motivation and improve recruitment and retention • skills and knowledge can be passed on and shared by employees Is it relevant to my business? Universities are keen to work with employers to ensure that courses reflect the real needs of business and industry and suit a wide range of training requirements. -

Exercising Freedom: Encounters with Art, Artists and Communities 6 October – 21 March 2021

Large Print Guide Exercising Freedom: Encounters with Art, Artists and Communities 6 October – 21 March 2021 Gallery 4 Please take this guide home. This document includes a large print version of the interpretation panel found by the entrance of Exercising Freedom: Encounters with Art, Artists and Communities in Gallery 4, as well as a large print version of the exhibition guide which is available inside the exhibition space. Document continues. Exercising Freedom: Encounters with Art, Artists and Communities 6 October – 21 March 2021 Gallery 4 Exercising Freedom: Encounters with Art, Artists and Communities this exhibition looks at the development of the community and education programme at the Whitechapel Gallery from 1979 to 1989. It presents rarely seen records from the Gallery’s archives which have not been widely researched to date. Walking through the doors of Whitechapel Art Gallery in the late 1970s, visitors could explore the wealth of arts from Bengal or immerse themselves in the abstract sculptures of American artist Eva Hesse. Facilitating these journeys was the Gallery’s pioneering Community Education Organiser Jenni Lomax, who developed a new approach to art and education and later became Director of Camden Art Centre. Document continues. For over a decade Lomax engaged young artists who often lived and worked in the area – including Zarina Bhimji, Sonia Boyce, Maria Chevska, Jocelyn Clarke, Fran Cottell, Sacha Craddock, Jeffrey Dennis, Charlie Hooker, Jefford Horrigan, Janis Jefferies, Rob Kesseler, Deborah Law, Bruce McLean, Stephen Nelson, Veronica Ryan, Allan de Souza, Jo Stockham – to act as creative mediators between the Gallery and East End communities, by forging partnerships with teachers, schools and local organisations. -

Annual Report 2019/20 Welcome Welcome

ANNUAL REPORT 2019/20 WELCOME WELCOME Welcome from Jayne Dickinson Contents Chief Executive College Group and Principal of East Surrey College Welcome .........................................................................3 It is with pride that I introduce this Annual Report as Chief Executive of Orbital South Colleges and Principal of East Surrey College. Merger on 1 February 2019, marked an important milestone for both East Meet the Team ...............................................................4 Surrey College and John Ruskin College and for local skills in our communities. This past year, it has been more important than ever to stand together to keep learning going while the pandemic has raged. And Financial Highlights ........................................................5 we certainly have. College Overview .......................................................6-7 Our brilliant staff worked tirelessly to move learning online, ensuring our students remained safe and our business intact. Working closely with schools, councils, businesses and external agencies, we kept Further Education ..........................................................8 students motivated about careers while also using the time to plan for our return to on-campus learning. A huge investment in John Ruskin College saw three brand new construction skills workshops established Higher Education ...........................................................9 over summer 2020 and a major new Construction Skills Centre opens its doors during summer 2021. Our -

Background Papers

ID CAPACITY TOWN ROAD VIEW COMMENTS As a cycle‐user I frequently use Walton Street both as a destination in its own right and also as a through‐route to and from the rail and coach stations, and West Oxford. The conditions for those who cycle have been immeasurably better since the junction was closed to motor traffic but still open to cycles and those on foot. The simplification of the junction makes a very big difference. Charlbury 9628641 individual Oxford Support That said, the remaining pedestrian crossing at Worcester Street North is now on the wrong alignment to Road facilitate southbound cycle‐users crossing the northbound vehicular flow as it turns into Beaumont Street. This needs urgent solution, now that traffic is rising again post‐COVID. Only when the Traffic Control Point proposed in Connecting Oxford is installed in Worcester Street, operating 24/7 year‐long, should the Walton Street junction be reopened to motor vehicles It is essential to reduce motorised transport both to reduce carbon emissions and to reduce the air pollution caused by motor vehicles. All vehicles cause pollution, including electric vehicles, which require CO2 emissions at power stations and generate particulates from road, brake and tyre wear. Eynsham 9642049 individual Oxford Support The experimental closure of Walton Street is one small step towards creating a safer, healthier and more Road civilised environment for walking and cycling, and reducing vehicle traffic. It should be extended indefinitely, and should be only the first step in a comprehensive suite of measures to eliminate private cars from the city, with the exception of those required by people with physical disabilities that prevent them from using foot, bicycle or public transport. -

HISTORIC LIBRARIES FORUM BULLETIN NO. 24 February 2013

HISTORIC LIBRARIES FORUM BULLETIN NO. 24 February 2013 It is a relief to report, after the bad news of libraries in danger in the previous bulletin and at our AGM in November, some good news. The Women’s Library has been found a safe home in the library of the London School of Economics, where it will continue to be available for use by both researchers and the general public, with its own dedicated space for exhibitions and teaching. Further details are on the LSE’s website: http://www2.lse.ac.uk/library/newsandinformation/newsArchive/2012/Womens- Library.aspx I reported at the AGM that rare books belonging to Wigan Public Library were sold off in October 2012, despite publicity in the local press and offers of advice from us. I helped a journalist from the Wigan Evening Post with some details of the books for sale. As a result of this sale we produced some guidance for public libraries with rare book collections, which was published on the Voices for the Library blog in November, hopefully to help public libraries before they get as far as selling off the books. The blog post can be seen here: http://www.voicesforthelibrary.org.uk/wordpress/?p=2703 As always, do continue to let us know of any libraries you hear of which may be in danger. We can only help to spread the word and help save the collections if we know about them! Both September’s provenance workshop and the annual meeting in November were over- subscribed and received excellent feedback from participants. -

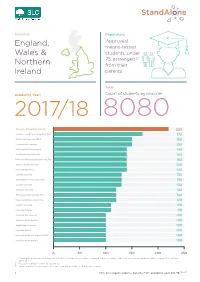

FOI 158-19 Data-Infographic-V2.Indd

Domicile: Population: Approved, England, means-tested Wales & students, under 25, estranged [1] Northern from their Ireland parents Total: Academic Year: Count of students by provider 2017/18 8080 Manchester Metropolitan University 220 Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU) 170 De Montfort University (DMU) 150 Leeds Beckett University 150 University Of Wolverhampton 140 Nottingham Trent University 140 University Of Central Lancashire (UCLAN) 140 Sheeld Hallam University 140 University Of Salford 140 Coventry University 130 Northumbria University Newcastle 130 Teesside University 130 Middlesex University 120 Birmingham City University (BCU) 120 University Of East London (UEL) 120 Kingston University 110 University Of Derby 110 University Of Portsmouth 100 University Of Hertfordshire 100 Anglia Ruskin University 100 University Of Kent 100 University Of West Of England (UWE) 100 University Of Westminster 100 0 50 100 150 200 250 1. “Estranged” means the customer has ticked the “You are irreconcilably estranged (have no contact with) from your parents and this will not change” box on their application. 2. Results rounded to nearest 10 customers 3. Where number of customers is less than 20 at any provider this has been shown as * 1 FOI | Estranged students data by HEP, academic year 201718 [158-19] Plymouth University 90 Bangor University 40 University Of Huddersfield 90 Aberystwyth University 40 University Of Hull 90 Aston University 40 University Of Brighton 90 University Of York 40 Staordshire University 80 Bath Spa University 40 Edge Hill -

Sealey 2003 Analysis

RADA R Oxford Brookes University – Research Archive and Digital Asset Repository (RADAR) Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy may be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. No quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. You must obtain permission for any other use of this thesis. Copies of this thesis may not be sold or offered to anyone in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright owner(s). When referring to this work, the full bibliographic details must be given as follows: Sealey, R. D. (2003). An analysis of the impact of privatisation and deregulation on the UK bus and coach and port industries. PhD thesis. Oxford Brookes University. www.brookes.ac.uk/go/radar Directorate of Learning Resources An analysis of the impact of privatisation and deregulation on the UK bus and coach and port industries Roger Derek Sealey Oxford Brookes University Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the award of Doctor of Philosophy November 2003 Acknowledgements There were many people who have assisted me this dissertation and I would like to take this opportunity of thanking them all. I would also like to thank: Eddy Batchelor, Librarian T&G Central Office; Malcolm Bee, Oxford Brookes University; Marinos Casparti, T&G Central Office; Bill Dewhurst, Ruskin College; Jim Durcan; Steve Edwards, Vice Chair, Passenger Transport Sector National Committee, T&G; -

Colleges Mergers 1993 to Date

Colleges mergers 1993 to date This spreadsheet contains details of colleges that were established under the 1992 Further and Higher Education Act and subsequently merged Sources: Learning and Skills Council, Government Education Departments, Association of Colleges College mergers under the Further Education Funding Council (FEFC) (1993-2001) Colleges Name of merged institution Local LSC area Type of merger Operative date 1 St Austell Sixth Form College and Mid-Cornwall College St Austell College Cornwall Double dissolution 02-Apr-93 Cleveland College of Further Education and Sir William Turner's Sixth 2 Cleveland Tertiary College Tees Valley Double dissolution 01-Sep-93 Form College 3 The Ridge College and Margaret Danyers College, Stockport Ridge Danyers College Greater Manchester Double dissolution 15-Aug-95 4 Acklam Sixth Form College and Kirby College of Further Education Middlesbrough College Tees Valley Double dissolution 01-Aug-95 5 Longlands College of Further Education and Marton Sixth Form College Teesside Tertiary College Tees Valley Double dissolution 01-Aug-95 St Philip's Roman Catholic Sixth Form College and South Birmingham 6 South Birmingham College Birmingham & Solihull Single dissolution (St Philips) 01-Aug-95 College North Warwickshire and Hinckley 7 Hinckley College and North Warwickshire College for Technology and Art Coventry & Warwickshire Double dissolution 01-Mar-96 College Mid-Warwickshire College and Warwickshire College for Agriculture, Warwickshire College, Royal 8 Coventry & Warwickshire Single dissolution -

Bishopsgate Conservation Area Draft Character Summary and Management Strategy SPD

City of London Bishopsgate Conservation Area Draft Character Summary and Management Strategy SPD Bishopsgate CA Draft Character Summary and Management Strategy SPD – Jan 2014 1 Introduction Character summary 1. Location and context 2. Designation history 3. Summary of character 4. Historical development Early history Eighteenth and nineteenth centuries Twentieth and twenty-first centuries 5. Spatial analysis Layout and plan form Building plots Building heights Views and vistas 6. Character analysis Bishopsgate Bishopsgate courts and alleys St Botolph without Bishopsgate Church and Churchyard Liverpool Street/Old Broad Street Wormwood Street Devonshire Row Devonshire Square New Street Middlesex Street Widegate Street Artillery Lane and Sandy’s Row Brushfield Street and Fort Street 7. Land uses and related activity 8. Traffic and transport 9. Architectural character Architects, styles and influences Building ages 10. Local details Architectural sculpture Public statuary and other features Blue plaques Historic signs Signage and shopfronts 11. Building materials 12. Open spaces and trees 13. Public realm 14. Cultural associations Bishopsgate CA Draft Character Summary and Management Strategy SPD – Jan 2014 2 Management strategy 15. Planning policy 16. Access and an inclusive environment 17. Environmental enhancement 18. Management of transport 19. Management of open spaces and trees 20. Archaeology 21. Enforcement 22. Condition of the conservation area Further reading and references Appendix Designated heritage assets Contacts Bishopsgate CA Draft Character Summary and Management Strategy SPD – Jan 2014 3 Introduction The present urban form and character of the City of London has evolved over many centuries and reflects numerous influences and interventions: the character and sense of place is hence unique to that area, contributing at the same time to the wider character of London. -

Report and Financial Statements for the Year Ended 31 July 2020

REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 JULY 2020 Key Management Personnel, Board of Governors and Professional advisers Key management personnel Key management personnel are defined as members of the College Leadership Team and were represented by the following in 2019/20: Mrs Jayne Dickinson - Chief Executive Officer (College Group) & Principal (ESC); Accounting Officer Mr Kevin Standish - Principal (John Ruskin College) & Quality Lead (College Group) Mrs Jyoti Baker - Chief Operating Officer (College Group) Mrs Mitzi Gibson – Executive Director HR & Professional Development (College Group) Board of Governors A full list of Governors is given on pages 18 and 19 of these financial statements. Mrs S Glover acted as Clerk to the Corporation throughout the period. Financial Statement and Regularity Auditor: Buzzacott 130 Wood Street London EC2V 6DL Internal Auditors: Scrutton Bland Fitzroy House Crown Street Ipswich, IP1 3LG Bankers: NatWest Bank Plc Barclays Bank PLC 2nd Floor Turnpike House 1 Churchill Place 123 High Street London E14 5HP Crawley, RH10 1DQ Solicitors: Mundays LLP Cedar House, 78, Portsmouth Road Cobham Surrey KT11 1AN Professional Advisors: Eversheds Buzzacott Cloth Hall Court 130 Wood Street Infirmary Street London Leeds EC2V 6DL LS1 2JB EAST SURREY COLLEGE 1 REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 JULY 2020 CONTENTS Page Report of the Governing Body 3 Statement of Corporate Governance and Internal Control 17 Governing Body’s Statement on the College’s Regularity, 25 Propriety and Compliance -

Colin Greenwood and His Christopher Dean Guitar

Castaway oxfordtimes.co.uk Colin Greenwood and his Christopher Dean guitar Photographs: Antony Moore 8 Oxfordshire Limited Edition September 2013 oxfordtimes.co.uk Castaway hat must it be like, as a member of a young rock band, to go from playing to tiny audiences in Wvillage halls and pubs to touring the USA and performing for audiences of 500 or more — with even more fans queuing around the block? And all in a matter of weeks. Multi-instrumentalist and composer Colin Greenwood, bass player with the iconic Oxford band Radiohead, knows that thrill. And it turns out that the USA has been good to Colin in many other ways — as it was where he met his wife, Molly. So what will Colin want to take to our desert island — and where did his journey to our island begin? “In 1969, my mother Brenda gave birth to me at the Radcliffe Infirmary in Oxford. But, until I was 11, we did not stay in one place for very long.” Colin said. “My father Ray served in the Royal Ordinance Corps, so the family moved to Germany and then to Didcot, Suffolk, Abingdon and Oakley. I attended five primary schools.” Where did his interest in music begin? “At home there was always music in the background. My parents’ favourite records were by Burl Ives, Scott Joplin, Simon and Garfunkel and Mozart’s horn concerto,” Colin, 44, said. “The important thing our parents did for my brother Jonny, sister Susan and I was to buy each of us musical instruments and encourage us to learn to play.