Summer 2017 Volume 20 Number 6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

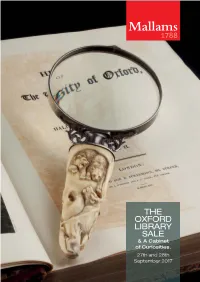

THE OXFORD LIBRARY SALE & a Cabinet of Curiosities

Mallams 1788 THE OXFORD LIBRARY SALE & A Cabinet of Curiosities. 27th and 28th September 2017 Chinese, Indian, Islamic & Japanese Art One of a pair of 25th & 26th October 2017 Chinese trade paintings, Final entries by September 27th 18th century £3000 – 4000 Included in the sale For more information please contact Robin Fisher on 01242 235712 or robin.fi[email protected] Mallams Auctioneers, Grosvenor Galleries, 26 Grosvenor Street Mallams Cheltenham GL52 2SG www.mallams.co.uk 1788 Jewellery & Silver A natural pearl, diamond and enamel brooch, with fitted Collingwood Ltd case Estimate £6000 - £8000 Wednesday 15th November 2017 Oxford Entries invited Closing date: 20th October 2017 For more information or to arrange a free valuation please contact: Louise Dennis FGA DGA E: [email protected] or T: 01865 241358 Mallams Auctioneers, Bocardo House, St Michael’s Street Mallams Oxford OX1 2EB www.mallams.co.uk 1788 BID IN THE SALEROOM Register at the front desk in advance of the auction, where you will receive a paddle number with which to bid. Take your seat in the saleroom and when you wish to bid, raide your paddle and catch the auctioneer’s attention. LEAVE A COMMISSION BID You may leave a commission bid via the website, by telephone, by email or in person at Mallams’ salerooms. Simply state the maximum price you would like to pay for a lot and we will purchase it for you at the lowest possible price, while taking the reserve price and other bids into account. BID OVER THE TELEPHONE Book a telephone line before the sale, stating which lots you would like to bid for, and we will call you in time for you to bid through one of our staff in the saleroom. -

River Cherwell Catchment Management Plan

NRA Thames 228 RIVER CHERWELL CATCHMENT MANAGEMENT PLAN DRAFT ACTION PLAN National Rivers Authority November 1995 Thames Region - West Area Isis House Howbery Park Wallingford Oxon 0X10 8BD KEY CATCHMENT STATISTICS Catchment area: 906 km2 Average Annual rainfall (1941-70): 682mm Total Main River length: 506km Population (estimate): 137,000 NRA National Rrvers Authority Thames Region General Features Local Authorities CMP Boundary Water Body Urban Areas Stratford-on-Avon West Oxfordshire Main Rivers Lock County Boundary' Daventry South Oxfordshire Non Main Rivers Motorway □ S. Northants. Oxford City Oxford Canal A Road Chcrwell Aylesbury Vale VISION 1-OR TIIE RIVER Cl IER WELL CATCHMENT In preparing the catchment visiou, the NRA has defined what it would wish the catchment to be aud the principle we will be following in working towards that visiou. The catchmeut visiou may not be something that cau be achieved iu the next five years, but something we can all work towards. Whilst the Cherwell Catchment lies largely within Oxfordshire it also encroaches into Buckinghamshire to the east and Warwickshire and Northamptonshire to the north. From its source at Charwelton to the Thames confluence, the river generally flows north to south and over a length of about 96 bn falls 100 metres, draining an area o f over 900 Ian2. Agriculture is the main land use in the catchment and has influenced the character of its countryside and landscape. The contribution made by the River Cherwell to the character of Oxfordshire in particular is recognised by several policies in the Structure Plan which seek to protect and enhance its natural features. -

OXONIENSIA PRINT.Indd 253 14/11/2014 10:59 254 REVIEWS

REVIEWS Joan Dils and Margaret Yates (eds.), An Historical Atlas of Berkshire, 2nd edition (Berkshire Record Society), 2012. Pp. xii + 174. 164 maps, 31 colour and 9 b&w illustrations. Paperback. £20 (plus £4 p&p in UK). ISBN 0-9548716-9-3. Available from: Berkshire Record Society, c/o Berkshire Record Offi ce, 9 Coley Avenue, Reading, Berkshire, RG1 6AF. During the past twenty years the historical atlas has become a popular means through which to examine a county’s history. In 1998 Berkshire inspired one of the earlier examples – predating Oxfordshire by over a decade – when Joan Dils edited an attractive volume for the Berkshire Record Society. Oxoniensia’s review in 1999 (vol. 64, pp. 307–8) welcomed the Berkshire atlas and expressed the hope that it would sell out quickly so that ‘the editor’s skills can be even more generously deployed in a second edition’. Perhaps this journal should modestly refrain from claiming credit, but the wish has been fulfi lled and a second edition has now appeared. Th e new edition, again published by the Berkshire Record Society and edited by Joan Dils and Margaret Yates, improves upon its predecessor in almost every way. Advances in digital technology have enabled the new edition to use several colours on the maps, and this helps enormously to reveal patterns and distributions. As before, the volume has benefi ted greatly from the design skills of the Department of Typography and Graphic Communication at the University of Reading. Some entries are now enlivened with colour illustrations as well (for example, funerary monuments, local brickwork, a workhouse), which enhance the text, though readers could probably have been left to imagine a fl ock of sheep grazing on the Downs. -

Land Off Warwick Road, North of Hanwell Fields, Banbury 12/01789

Land off Warwick Road, North of 12/01789/OUT Hanwell Fields, Banbury Ward: Banbury Hardwick and District Councillors: Councillor Donaldson, Wroxton Councillor Ilott, Councillor Turner and Councillor Webb Case Officer: Jane Dunkin/Tracey Recommendation: Approval Morrissey Applicant: Persimmon Homes Ltd Application Description: Outline application for up to 350 dwellings, together with new vehicular access from Warwick Road an associated open space Committee Referral: Major Application (exceeds 10 dwellings and 1ha) and Departure from Policy 1. Site Description and Proposed Development 1.1 The application was deferred from last month’s meeting to allow for the current focussed consultation exercise to be completed which allowed for representations to be received by 23 rd May 2013 (consultation expiry date). The consultation period has now closed and the representations that have been received will be reported to the Executive in due course. Although these comments are presently unresolved, for the purposes of considering this current application, the Council has a continuing obligation to determine planning applications as and when submitted, on the basis of existing policy and other material considerations. Therefore it cannot, in effect, create a hiatus in determining planning applications pending the examination of its emerging local plan. 1.2 The application relates to a site that has been identified for residential development in the Proposed Submission Local Plan Incorporating Proposed Changes (March 2013) (PSLPIPC). The site as a whole covers an area of some 20.2ha and forms the greater part of the approx 26ha allocated site to the north of Dukes Meadow Drive and to the east of Warwick Road. -

39 Windrush Banbury, Oxfordshire, OX16

39 Windrush Banbury 39 Windrush Banbury, Oxfordshire, OX16 1PL Approximate distances Banbury town centre 1 mile Banbury train station 1.25 miles Oxford 21 miles Stratford upon Avon 20 miles Leamington Spa 19 miles Banbury to Marylebone by rail approx. 55 mins Banbury to Oxford by rail approx. 17 mins Banbury to Birmingham by rail approx. 50 mins A WELL PRESENTED THREE BEDROOMED SEMI DETACHED HOUSE WITH SPACIOUS LIVING ACCOMMODATION LOCATED CLOSE TO ALL DAILY AMENITIES. Entrance hallway, cloakroom/WC, sitting room/dining room, kitchen, two double bedrooms, one single bedroom, family bathroom, uPVC double glazing, gas central heating, enclosed rear garden, overlooking green. £210,000 FREEHOLD Directions green area. From Banbury town centre proceed in a Northerly direction along the Southam * Spacious entrance hallway with stairs Road (A423). At the large roundabout rising to first floor, and doors leading to before Tesco supermarket turn left into the cloakroom, kitchen, sitting room, Ruscote Avenue and follow the road and two storage cupboards. until reaching a mini roundabout and then turn right into Longelandes Way. * Downstairs cloakroom consists of a Having past the shops on the left, take low level w/c, and hand wash basin. the second left hand turning in which it's signed No's 20-45 Windrush. Once * The sitting room is located to the parked, follow the pathway round to front of the house and leads into the the front of the houses in which you open plan dining area. The dining area will find number 39 on your right, after has wood effect laminate flooring and following the numbering system. -

Cake and Cockhorse

CAKE AND COCKHORSE BANBURY HISTORICAL SOCIETY Summer 2012 £2.50 Volume 18 Number 9 ISSN 6522-0823 BANBURY HISTORICAL SOCIETY Registered Charity No. 269581 Website: www.banburyhistory.org President The Lord Saye and Sele Chairman Dr Barrie Trinder, 5 Wagstaff Way, Olney, Bucks. MK46 5FD (tel. 01234 712009; email: <[email protected]>) Cake and Cockhorse Editorial Committee Editor: Jeremy Gibson, Harts Cottage, Church Hanborough, Witney, Oxon. OX29 8AB (tel. 01993 882982; email: <[email protected]>) Assistant editors: Deborah Hayter (commissioning), Beryl Hudson (proofs) Hon. Secretary: Hon. Treasurer: Simon Townsend, G.F. Griffiths, Banbury Museum, 39 Waller Drive, Spiceball Park Road, Banbury, Banbury OX16 2PQ Oxon. OX16 9NS; (tel. 01295 753781; email: (tel. 01295 263944; email: <[email protected]>) <[email protected]>). Publicity: Hon. Research Adviser: Deborah Hayter, Brian Little, Walnut House, 12 Longfellow Road, Charlton, Banbury, Banbury OX17 3DR Oxon. OX16 9LB; (tel. 01295 811176; email: (tel. 01295 264972). <[email protected]>) Other Committee Members Colin Cohen, Chris Day, Helen Forde, Beryl Hudson, Clare Jakeman Membership Secretary Mrs Margaret Little, c/o Banbury Museum, Spiceball Park Road, Banbury, Oxon. OX16 2PQ (email: <[email protected]>). Details of the Society's activities and publications will be found on the back cover. © 2012 Banbury Historical Society on behalf of its contributors. Cake and Cockhorse The magazine of the Banbury Historical Society, issued three times a year. Volume 18 Summer 2012 Number Nine Joyce Hoad, Swing in Banburyshire: ed. Barrie Trinder New light on the riots of 1830 286 John Dunleavy Maffiking at Banbury: Official and Unofficial 301 Deborah Hayter Snippets from the Archives: 5. -

Cropredy Bridge by MISS M

Cropredy Bridge By MISS M. R. TOYNBEE and J. J. LEEMING I IE bridge over the River Chenveff at Cropredy was rebuilt by the Oxford shire County Council in J937. The structure standing at that time was for T the most part comparatively modern, for the bridge, as will be explained later, has been thoroughly altered and reconstructed at least twice (in J780 and 1886) within the last 160 years. The historical associations of the bridge, especiaffy during the Civil War period, have rendered it famous, and an object of pilgrimage, and it seems there fore suitable, on the occasion of its reconstruction, to collect together such details as are known about its origin and history, and to add to them a short account of the Civil War battle of 1644, the historical occurrence for which the site is chiefly famous. The general history of the bridge, and the account of the battle, have been written by Miss Toynbee; the account of the 1937 reconstruction is by Mr. Leeming, who, as engineer on the staff of the Oxfordshire County Council, was in charge of the work. HISTORY OF TIlE BRIDGE' The first record of the existence of a bridge at Cropredy dates, so far as it has been possible to discover, from the year 1312. That there was a bridge in existence before 1312 appears to be pretty certain. Cropredy was a place of some importance in the :\1iddle Ages. It formed part of the possessions of the See of Lincoln, and is entered in Domesday Book as such. 'The Bishop of Lincoln holds Cropelie. -

Clifton Past and Present

Clifton Past and Present L.E. Gardner, 1955 Clifton, as its name would imply, stands on the side of a hill – ‘tun’ or ‘ton’ being an old Saxon word denoting an enclosure. In the days before the Norman Conquest, mills were grinding corn for daily bread and Clifton Mill was no exception. Although there is no actual mention by name in the Domesday Survey, Bishop Odo is listed as holding, among other hides and meadows and ploughs, ‘Three Mills of forty one shillings and one hundred ells, in Dadintone’. (According to the Rev. Marshall, an ‘ell’ is a measure of water.) It is quite safe to assume that Clifton Mill was one of these, for the Rev. Marshall, who studied the particulars carefully, writes, ‘The admeasurement assigned for Dadintone (in the survey) comprised, as it would seem, the entire area of the parish, including the two outlying townships’. The earliest mention of the village is in 1271 when Philip Basset, Baron of Wycomb, who died in 1271, gave to the ‘Prior and Convent of St Edbury at Bicester, lands he had of the gift of Roger de Stampford in Cliftone, Heentone and Dadyngtone in Oxfordshire’. Another mention of Clifton is in 1329. On April 12th 1329, King Edward III granted a ‘Charter in behalf of Henry, Bishop of Lincoln and his successors, that they shall have free warren in all their demesne, lands of Bannebury, Cropperze, etc. etc. and Clyfton’. In 1424 the Prior and Bursar of the Convent of Burchester (Bicester) acknowledged the receipt of thirty-seven pounds eight shillings ‘for rent in Dadington, Clyfton and Hampton’. -

Vebraalto.Com

64, High Street, Croughton, NN13 5LT Guide price £315,000 A beautifully presented and completely refurbished two bedroom stone built cottage in the heart of Croughton. With many original features and an abundance of charm and character this cottage has a south facing garden and a stone built outbuilding which offers the flexibility for a home office or games room. This delightful stone built cottage has been To the first floor the master bedroom with its Estate is just a short drive away where you can completely renovated and finished to exacting Vaulted ceiling, en‐suit and walk in wardrobes enjoy cycle rides and take the dog for a long walk standards by the present owners to provide enjoys views over the front garden. There is a around the stunning grounds. Evenley also has a practical accommodation, whilst retaining many of further double bedroom and family bathroom which good range of facilities including a church, public the original features and the charm. have been completely refurbished. house, The Red Lion, and a good village shop and post office. There is also a lovely village green It is the ideal property for those who wish to be Outside the property is approached via a pretty which is used regularly during the summer season part of a village community whilst avoiding the footpath serving just two cottages, gated access for cricket matches. hustle and bustle of everyday living, making it the leads to the front garden, which is enclosed by perfect "Escape To The Country". mature hedging, a stone wall and wrought iron There are two very good local preparatory schools, railing. -

Cake and Cockhorse

Cake and Cockhorse The magazine of the Banbury Historical Society, issued three times a year. Volume 16 Number Two Spring 2004 Thomas Ward Boss Reminiscences of Old Banbury (in 1903) 50 Book Reviews Nicholas Cooper The Lost Architectural Landscapes of Warwickshire: Vol. 1 — The South, Peter Bolton 78 Nicholas J. Allen Village Chapels: Some Aspects of rural Methodism in the East Cotswolds and South Midlands, 1800-2000, Pauline Ashridge 79 Brian Little Lecture Reports 80 Peter Gaunt The Cromwell Association at Banbury, 24 April 2004 83 Obituaries Brian Little Ted Clark ... ... ... 84 Barrie Trinder Professor Margaret Stacey ... 85 Banbury Historical Society Annual Report and Accounts, 2003 86 In our Summer 2003 issue (15.9) Barrie Trinder wrote about the various memoirs of Banbury in the last two centuries. With sixteen subjects he could only devote a paragraph to each. One that caught my eye was Thomas Ward Boss (born 1825), long-time librarian at the Mechanics' Institute. Then I realised I had a copy of the published version of his talk delivered one hundred and one years ago, in March 1903. Re-reading it, I found it quite absorbing, a wonderful complement to George Herbert's famous Shoemaker's Window, a reminiscence of Banbury in the 1830s and later. On the assumption that few are likely to track down copies in local libraries, it seems well worthwhile to reprint it here, from the original Cheney's version. There are a few insignificant misprints, but, especially in view of the sad demise of our oldest Banbury business, it is good to reprint a typical piece of their work. -

Cake and Cockhorse

CAKE AND COCKHORSE Banbury Historical Society Autumn 1973 BANBURY HISTORICAL SOCIETY President: The Lord Saye and Sele Chairman and Magazine Editor: F. Willy, B.A., Raymond House, Bloxham School, Banbury Hon. Secretary: Assistant Secretary Hon. Treasurer: Miss C.G. Bloxham, B.A. and Records Series Editor: Dr. G.E. Gardam Banbury Museum J.S.W. Gibson, F.S.A. 11 Denbigh Close Marlborough Road 1 I Westgate Broughton Road Banbury OX 16 8 DF Chichester PO 19 3ET Banbury OX1 6 OBQ (Tel. Banbury 2282) (Chichester 84048) (Tel. Banbury 2841) Hon. Research Adviser: Hon. Archaeological Adviser: E.R.C. Brinkworth, M.A., F.R.Hist.S. J.H. Fearon, B.Sc. Committee Members J.B. Barbour, A. Donaldson, J.F. Roberts ************** The Society was founded in 1957 to encourage interest in the history of the town of Banbury and neighbouring parts of Oxfordshire, Northamptonshire and Warwickshire. The Magazine Cake & Cockhorse is issued to members three times a year. This includes illustrated articles based on original local historical research, as well as recording the Society’s activities. Publications include Old Banbury - a short popular history by E.R.C. Brinkworth (2nd edition), New Light on Banbury’s Crosses, Roman Banburyshire, Banbury’s Poor in 1850, Banbury Castle - a summary of excavations in 1972, The Building and Furnishing of St. Mary’s Church, Banbury, and Sanderson Miller of Radway and his work at Wroxton, and a pamphlet History of Banbury Cross. The Society also publishes records volumes. These have included Clockmaking in Oxfordshire, 1400-1850; South Newington Churchwardens’ Accounts 1553-1684; Banbury Marriage Register, 1558-1837 (3 parts) and Baptism and Burial Register, 1558-1723 (2 parts); A Victorian M.P. -

Electoral Changes) Order 2015

Draft Order laid before Parliament under section 59(9) of the Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act 2009; draft to lie for forty days pursuant to section 6(1) of the Statutory Instruments Act 1946, during which period either House of Parliament may resolve that the Order be not made. DRAFT STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2015 No. LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The Cherwell (Electoral Changes) Order 2015 Made - - - - Coming into force in accordance with article 1(2) and (3) Under section 58(4) of the Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act 2009( a) (“the Act”) the Local Government Boundary Commission for England(b) (“the Commission”) published a report dated May 2015 stating its recommendations for changes to the electoral arrangements for the district of Cherwell. The Commission has decided to give effect to the recommendations. A draft of the instrument has been laid before Parliament and a period of forty days has expired and neither House has resolved that the instrument be not made. The Commission makes the following Order in exercise of the power conferred by section 59(1) of the Act: Citation and commencement 1. —(1) This Order may be cited as the Cherwell (Electoral Changes) Order 2015. (2) Except for article 6, this Order comes into force— (a) for the purpose of proceedings preliminary or relating to the election of councillors, on the day after it is made; (b) for all other purposes, on the ordinary day of election of councillors in 2016. (3) Article 6 comes into force— (a) for the purpose of proceedings preliminary or relating to the election of councillors, on 15th October 2018; (b) for all other purposes, on the ordinary day of election of councillors in 2019.