Bill Spiller Pioneer Forced PGA to Change Its Ways by Al Barkow 68 to Tie for Second with No Less Than Here Is a Theory of History That Ben Hogan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 MASSACHUSETTS OPEN CHAMPIONSHIP June 10-12, 2019 Vesper Country Club Tyngsborough, MA

2019 MASSACHUSETTS OPEN CHAMPIONSHIP June 10-12, 2019 Vesper Country Club Tyngsborough, MA MEDIA GUIDE SOCIAL MEDIA AND ONLINE COVERAGE Media and parking credentials are not needed. However, here are a few notes to help make your experience more enjoyable. • There will be a media/tournament area set up throughout the three-day event (June 10-12) in the club house. • Complimentary lunch and beverages will be available for all media members. • Wireless Internet will be available in the media room. • Although media members are not allowed to drive carts on the course, the Mass Golf Staff will arrange for transportation on the golf course for writers and photographers. • Mass Golf will have a professional photographer – David Colt – on site on June 10 & 12. All photos will be posted online and made available for complimentary download. • Daily summaries – as well as final scores – will be posted and distributed via email to all media members upon the completion of play each day. To keep up to speed on all of the action during the day, please follow us via: • Twitter – @PlayMassGolf; #MassOpen • Facebook – @PlayMassGolf; #MassOpen • Instagram – @PlayMassGolf; #MassOpen Media Contacts: Catherine Carmignani Director of Communications and Marketing, Mass Golf 300 Arnold Palmer Blvd. | Norton, MA 02766 (774) 430-9104 | [email protected] Mark Daly Manager of Communications, Mass Golf 300 Arnold Palmer Blvd. | Norton, MA 02766 (774) 430-9073 | [email protected] CONDITIONS & REGULATIONS Entries Exemptions from Local Qualifying Entries are open to professional golfers and am- ateur golfers with an active USGA GHIN Handi- • Twenty (20) lowest scorers and ties in the 2018 cap Index not exceeding 2.4 (as determined by Massachusetts Open Championship the April 15, 2019 Handicap Revision), or who have completed their handicap certification. -

2019-20 PGA TOUR Schedule

2019-20 PGA TOUR Schedule 2019-20 FedExCup Season (49 events) DATE TOURNAMENT TV NETWORKS GOLF COURSE(S) LOCATION S 9-15 A Military Tribute at the Greenbrier GOLF The Greenbrier Resort (The Old White TPC) White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia 16-22 Sanderson Farms Championship GOLF Country Club of Jackson Jackson, Mississippi 23-29 Safeway Open GOLF Silverado Resort and Spa (North Course) Napa, California O 30-6 Shriners Hospitals for Children Open GOLF TPC Summerlin Las Vegas, Nevada 7-13 Houston Open GOLF Golf Club of Houston Humble, Texas 14-20 THE CJ CUP @ NINE BRIDGES GOLF The Club at Nine Bridges Jeju Island, Korea 21-27 The ZOZO CHAMPIONSHIP GOLF Accordia Golf Narashino Country Club Chiba Prefecture, Japan N 28-3 World Golf Championships-HSBC Champions GOLF Sheshan International Golf Club Shanghai, China 28-3 Bermuda Championship GOLF Port Royal Golf Club Southampton, Bermuda 4-10 OFF 11-17 Mayakoba Golf Classic GOLF El Camaleón Golf Club at the Mayakoba Resort Playa del Carmen, Mexico 18-24 The RSM Classic GOLF Sea Island Resort (*Seaside Course, Plantation Course) St. Simons Island, Georgia D 25-1 OFF 2-8 OFF 9-15 Presidents Cup GOLF / NBC Royal Melbourne Golf Club Black Rock, Victoria, Australia BREAK J 30-5 Sentry Tournament of Champions GOLF Kapalua Resort (The Plantation Course) Kapalua, Hawaii 6-12 Sony Open in Hawaii GOLF Waialae Country Club Honolulu, Hawaii PGA WEST (*Stadium Course, Nicklaus Tournament Course); 13-19 Desert Classic GOLF La Quinta, California La Quinta Country Club 20-26 Farmers Insurance Open GOLF / CBS -

1950-1959 Section History

A Chronicle of the Philadelphia Section PGA and its Members by Peter C. Trenham 1950 to 1959 Contents 1950 Ben Hogan won the U.S. Open at Merion and Henry Williams, Jr. was runner-up in the PGA Championship. 1951 Ben Hogan won the Masters and the U.S. Open before ending his eleven-year association with Hershey CC. 1952 Dave Douglas won twice on the PGA Tour while Henry Williams, Jr. and Al Besselink each won also. 1953 Al Besselink, Dave Douglas, Ed Oliver and Art Wall each won tournaments on the PGA Tour. 1954 Art Wall won at the Tournament of Champions and Dave Douglas won the Houston Open. 1955 Atlantic City hosted the PGA national meeting and the British Ryder Cup team practiced at Atlantic City CC. 1956 Mike Souchak won four times on the PGA Tour and Johnny Weitzel won a second straight Pennsylvania Open. 1957 Joe Zarhardt returned to the Section to win a Senior Open put on by Leo Fraser and the Atlantic City CC. 1958 Marty Lyons and Llanerch CC hosted the first PGA Championship contested at stroke play. 1959 Art Wall won the Masters, led the PGA Tour in money winnings and was named PGA Player of the Year. 1950 In early January Robert “Skee” Riegel announced that he was turning pro. Riegel who had grown up in east- ern Pennsylvania had won the U.S. Amateur in 1947 while living in California. He was now playing out of Tulsa, Oklahoma. At that time the PGA rules prohibited him from accepting any money on the PGA Tour for six months. -

1940-1949 Section History

A Chronicle of the Philadelphia Section PGA and its Members by Peter C. Trenham 1940 to 1949 Contents 1940 Hershey CC hosted the PGA and Section member Sam Snead lost in the finals to Byron Nelson. 1941 The Section hosted the 25 th anniversary dinner for the PGA of America and Dudley was elected president. 1942 Sam Snead won the PGA at Seaview and nine Section members qualified for the 32-man field. 1943 The Section raised money and built a golf course for the WW II wounded vets at Valley Forge General Hospital. 1944 The Section was now providing golf for five military medical hospitals in the Delaware Valley. 1945 Hogan, Snead and Nelson, won 29 of the 37 tournaments held on the PGA Tour that year. 1946 Ben Hogan won 12 events on the PGA Tour plus the PGA Championship. 1947 CC of York pro E.J. “ Dutch” Harrison won the Reading Open, plus two more tour titles. 1948 Marty Lyons was elected secretary of the PGA. Ben Hogan won the PGA Championship and the U.S. Open. 1949 In January Hogan won twice and then a collision with a bus in west Texas almost ended his life. 1940 The 1940s began with Ed Dudley, Philadelphia Country Club professional, in his sixth year as the Section president. The first vice-president and tournament chairman, Marty Lyons, agreed to host the Section Champion- ship for the fifth year in a row at the Llanerch Country Club. The British Open was canceled due to war in Europe. The third PGA Seniors’ Championship was held in mid January. -

June 2020 Newsletter

President's Message They say that this is the new normal and I can’t say that I like it but it seems like things have started to improve over the way that they were. People are able to get out and about a little easier and we are now starting to plan for upcoming golf tournaments! The course is in the best condition that it has ever been and kudos go out to our maintenance staff and Superintendent. The weekends are very busy and the new tee time format seems to be working out just fine, I have heard nothing but compliments from all of our members. I just want to remind everyone that we still have to follow the social distancing rules both on and off the course. Even though we are now in Phase 2 and will soon be in Phase 3, we can’t let our guard down or we could suffer setbacks in the spread of the virus. As always, if you want to reach me to discuss anything, please send me an email at roger.laime@aecom or call me on my cell phone at 518-772-7754. Please be considerate of others, be safe and think warm weather. Roger Laime Treasurer’s Report June 15th, 2020 I want all of our members to be aware, especially our newer members that you will see a bunker renovation fee on your July invoice. This is our final year of our 5 year bunker renovation project as Steve and his staff have recently completed #13. The fee will be 3% of dues for your membership category. -

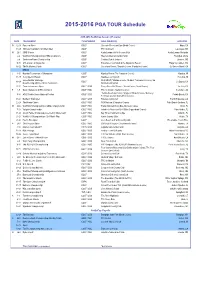

2015-16 PGA TOUR Schedule for RELEASE

2015-2016 PGA TOUR Schedule 2015-2016 FedExCup Season (47 events) DATE TOURNAMENT TV NETWORKS GOLF COURSE(S) LOCATION O 12-18 Frys.com Open GOLF Silverado Resort and Spa (North Course) Napa. CA 19-25 Shriners Hospitals for Children Open GOLF TPC Summerlin Las Vegas, NV N 26-1 CIMB Classic GOLF Kuala Lumpur Golf & Country Club Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 2-8 World Golf Championships-HSBC Champions GOLF Sheshan International Golf Club Shanghai, China 2-8 Sanderson Farms Championship GOLF Country Club of Jackson Jackson, MS 9-15 OHL Classic at Mayakoba GOLF El Camaleon Golf Club at the Mayakoba Resort Playa del Carmen, MX 16-22 The McGladrey Classic GOLF Sea Island Resort (*Seaside Course, Plantation Course) St. Simons Island, GA BREAK J 4-10 Hyundai Tournament of Champions GOLF Kapalua Resort (The Plantation Course) Kapalua, HI 11-17 Sony Open in Hawaii GOLF Waialae Country Club Honolulu, HI CareerBuilder Challenge PGA WEST (*Stadium Course, Nicklaus Tournament Course); La 18-24 GOLF La Quinta, CA in partnership with the Clinton Foundation Quinta Country Club 25-31 Farmers Insurance Open GOLF / CBS Torrey Pines Golf Course (*South Course, North Course) La Jolla, CA F 1-7 Waste Management Phoenix Open GOLF / NBC TPC Scottsdale (Stadium Course) Scottsdale, AZ *Pebble Beach Golf Links, Spyglass Hill Golf Course, Monterey 8-14 AT&T Pebble Beach National Pro-Am GOLF / CBS Pebble Beach, CA Peninsula Country Club (Shore Course) 15-21 Northern Trust Open GOLF / CBS Riviera Country Club Pacific Palisades, CA 22-28 The Honda Classic GOLF / NBC PGA National -

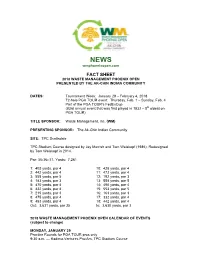

Fact Sheet 2018 Waste Management Phoenix Open Presented by the Ak-Chin Indian Community

NEWS wmphoenixopen.com FACT SHEET 2018 WASTE MANAGEMENT PHOENIX OPEN PRESENTED BY THE AK-CHIN INDIAN COMMUNITY DATES: Tournament Week: January 29 – February 4, 2018 72-hole PGA TOUR event: Thursday, Feb. 1 – Sunday, Feb. 4 Part of the PGA TOUR's FedExCup (83rd annual event that was first played in 1932 – 5th oldest on PGA TOUR) TITLE SPONSOR: Waste Management, Inc. (WM) PRESENTING SPONSOR: The Ak-Chin Indian Community SITE: TPC Scottsdale TPC Stadium Course designed by Jay Morrish and Tom Weiskopf (1986), Redesigned by Tom Weiskopf in 2014. Par: 35-36--71, Yards: 7,261 1: 403 yards, par 4 10: 428 yards, par 4 2: 442 yards, par 4 11: 472 yards, par 4 3: 558 yards, par 5 12: 192 yards, par 3 4: 183 yards, par 3 13: 558 yards, par 5 5: 470 yards, par 4 14: 490 yards, par 4 6: 432 yards, par 4 15: 553 yards, par 5 7: 215 yards, par 3 16: 163 yards, par 3 8: 475 yards, par 4 17: 332 yards, par 4 9: 453 yards, par 4 18: 442 yards, par 4 Out: 3,631 yards, par 35 In: 3,630 yards, par 3 2018 WASTE MANAGEMENT PHOENIX OPEN CALENDAR OF EVENTS (subject to change) MONDAY, JANUARY 29 Practice Rounds for PGA TOUR pros only 9:30 a.m. — Kadima.Ventures Pro-Am, TPC Stadium Course TUESDAY, JANUARY 30 Practice Rounds for PGA TOUR pros only 10:00 a.m. — R.S. Hoyt Jr. Family Foundation Dream Day Activities • Motivational Speeches by PGA TOUR Professionals • Trick Shot Show • Junior Golf Clinic Presented by PING • Located on the TPC Champions Course Practice Range 11:00 a.m. -

2018-19 PGA TOUR Schedule

2018-19 PGA TOUR Schedule 2018-2019 PGA TOUR Season (46 events) DATE TOURNAMENT TV NETWORKS GOLF COURSE(S) LOCATION PURSE O 1-7 Safeway Open GOLF Silverado Resort and Spa (North Course) Napa, California 6.4 8-14 CIMB Classic GOLF TPC Kuala Lumpur Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 7.0 15-21 THE CJ CUP @ NINE BRIDGES GOLF Nine Bridges Jeju Island, Korea 9.5 22-28 World Golf Championships-HSBC Champions GOLF Sheshan International Golf Club Shanghai, China 10.0 22-28 Sanderson Farms Championship GOLF Country Club of Jackson Jackson, Mississippi 4.4 N 29-4 Shriners Hospitals for Children Open GOLF TPC Summerlin Las Vegas, Nevada 7.0 5-11 Mayakoba Golf Classic GOLF El Camaleon Golf Club at the Mayakoba Resort Playa del Carmen, Mexico 7.2 12-18 The RSM Classic GOLF Sea Island Resort (*Seaside Course, Plantation Course) St. Simons Island, Georgia 6.4 BREAK J 31-6 Sentry Tournament of Champions GOLF Kapalua Resort (The Plantation Course) Kapalua, Hawaii 6.5 7-13 Sony Open in Hawaii GOLF Waialae Country Club Honolulu, Hawaii 6.4 PGA WEST (*Stadium Course, Nicklaus Tournament Course); 14-20 Desert Classic GOLF La Quinta, California 5.9 La Quinta Country Club 21-27 Farmers Insurance Open GOLF / CBS Torrey Pines Golf Course (*South Course, North Course) San Diego, California 7.1 F 28-3 Waste Management Phoenix Open GOLF / NBC TPC Scottsdale (Stadium Course) Scottsdale, Arizona 7.1 *Pebble Beach Golf Links, Spyglass Hill Golf Course, Monterey 4-10 AT&T Pebble Beach Pro-Am GOLF / CBS Pebble Beach, California 7.6 Peninsula Country Club (Shore Course) 11-17 Genesis -

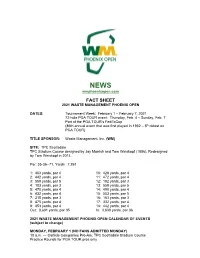

2021 Fact Sheet

NEWS wmphoenixopen.com FACT SHEET 2021 WASTE MANAGEMENT PHOENIX OPEN DATES: Tournament Week: February 1 – February 7, 2021 72-hole PGA TOUR event: Thursday, Feb. 4 – Sunday, Feb. 7 Part of the PGA TOUR's FedExCup (86th annual event that was first played in 1932 – 5th oldest on PGA TOUR) TITLE SPONSOR: Waste Management, Inc. (WM) SITE: TPC Scottsdale TPC Stadium Course designed by Jay Morrish and Tom Weiskopf (1986), Redesigned by Tom Weiskopf in 2014. Par: 35-36--71, Yards: 7,261 1: 403 yards, par 4 10: 428 yards, par 4 2: 442 yards, par 4 11: 472 yards, par 4 3: 558 yards, par 5 12: 192 yards, par 3 4: 183 yards, par 3 13: 558 yards, par 5 5: 470 yards, par 4 14: 490 yards, par 4 6: 432 yards, par 4 15: 553 yards, par 5 7: 215 yards, par 3 16: 163 yards, par 3 8: 475 yards, par 4 17: 332 yards, par 4 9: 453 yards, par 4 18: 442 yards, par 4 Out: 3,631 yards, par 35 In: 3,630 yards, par 36 2021 WASTE MANAGEMENT PHOENIX OPEN CALENDAR OF EVENTS (subject to change) MONDAY, FEBRUARY 1 (NO FANS ADMITTED MONDAY) 10 a.m. — Carlisle Companies Pro-Am, TPC Scottsdale Stadium Course Practice Rounds for PGA TOUR pros only TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 2 (NO FANS ADMITTED TUESDAY) Practice Rounds for PGA TOUR pros only WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 3 8:30 a.m. — Annexus Pro-Am, TPC Scottsdale Stadium Course 3:30 p.m. — Phoenix Suns Charities Shot at Glory, TPC Scottsdale 16th hole THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 4 7:30 a.m. -

Pga Golf Professional Hall of Fame

PGA MEDIA GUIDE 2012 PGA GOLF PROFESSIONAL HALL OF FAME On Sept. 8, 2005, The PGA of America honored 122 PGA members who have made significant and enduring contributions to The PGA of America and the game of golf, with engraved granite bricks on the south portico of the PGA Museum of Golf in Port St. Lucie, Fla. That group included 44 original inductees between 1940 and 1982, when the PGA Golf Professional Hall of Fame was located in Pinehurst, N.C. The 2005 Class featured then-PGA Honorary President M.G. Orender of Jacksonville Beach, Fla., and Craig Harmon, PGA Head Professional at Oak Hill Country Club in Rochester, N.Y., and the 2004 PGA Golf Professional of the Year. Orender led a delegation of 31 overall Past Presidents into the Hall, a list that begins with the Association’s first president, Robert White, who served from 1916-1919. Harmon headed a 51-member group who were recipients of The PGA’s highest honor — PGA Golf Professional of the Year. Dedicated in 2002, The PGA of America opened the PGA PGA Hall of Fame 2011 inductees (from left) Guy Wimberly, Jim Remy, Museum of Golf in PGA Village in Port St. Lucie, Fla., which Jim Flick, Errie Ball, Jim Antkiewicz and Jack Barber at the Hall paved the way for a home for the PGA Golf Professional Hall of Fame Ceremony held at the PGA Education Center at PGA Village of Fame. in Port St. Lucie, Florida. (Jim Awtrey, Not pictured) The PGA Museum of Golf celebrates the growth of golf in the United States, as paralleled by the advancement of The Professional Golfers’ Association of America. -

PGA of America Awards

THE 2006 PGA MEDIA GUIDE – 411 PGA of America Awards ¢ PGA Player of the Year The PGA Player of the Year Award is given to the top PGA Tour player based on his tournament wins, official money standing and scoring average. The point system for selecting the PGA Player of the Year was amended in 1982 and is as follows: 30 points for winning the PGA Championship, U.S. Open, British Open or Masters; 20 points for winning The Players Championship; and 10 points for winning all other designated PGA Tour events. In addition, there is a 50-point bonus for winning two majors, 75-point bonus for winning three, 100-point bonus for winning four. For top 10 finishes on the PGA Tour’s official money and scoring average lists for the year, the point value is: first, 20 points, then 18, 16, 14, 12, 10, 8, 6, 4, 2. Any incomplete rounds in the scoring average list will result in a .10 penalty per incomplete round. 1948 Ben Hogan 1960 Arnold Palmer 1972 Jack Nicklaus 1984 Tom Watson Tiger Woods 1949 Sam Snead 1961 Jerry Barber 1973 Jack Nicklaus 1985 Lanny Wadkins 1950 Ben Hogan 1962 Arnold Palmer 1974 Johnny Miller 1986 Bob Tway 1996 Tom Lehman 1951 Ben Hogan 1963 Julius Boros 1975 Jack Nicklaus 1987 Paul Azinger 1997 Tiger Woods 1952 Julius Boros 1964 Ken Venturi 1976 Jack Nicklaus 1988 Curtis Strange 1998 Mark O’Meara 1953 Ben Hogan 1965 Dave Marr 1977 Tom Watson 1989 Tom Kite 1999 Tiger Woods 1954 Ed Furgol 1966 Billy Casper 1978 Tom Watson 1990 Nick Faldo 2000 Tiger Woods 1955 Doug Ford 1967 Jack Nicklaus 1979 Tom Watson 1991 Corey Pavin 2001 Tiger Woods 1956 Jack Burke Jr. -

PPCO Twist System

Welcome to the April issue of digital Golf Range Magazine! Inside the April issue, you will find the following features: • Business of Teaching: Marketing to the Serious Golfer – The high- income, high-frequency golfer who says that score is important to enjoyment of the game is—or could be—a cornerstone of your instruction program. • Clubfitting: Making Demo Day More about the Pro – Major golf gear brands deliver excitement during Demo Day events, but increasingly they’re turning the spotlight back onto on-site professionals. • Resort Range Profile: Four Seasons Dallas – The glory days of corporate golf schools ended abruptly several years ago—except at Four Seasons in Dallas. In case you forgot the formula, here’s how they spell success. • Range Marketing: Catching Golfers in Your Website – Ranges like Man O’War Golf Learning Center take a workhorse approach to their websites—making sure that customer data, engagement and revenue are top priorities. Keep it fun and thanks for supporting the GRAA. Best Regards, Rick Summers, CEO GRAA [email protected] VIDEO: SUSAN ROLL • GOLF RANGE NEWS • CREATE A CUSTOMER SURVEY Golf RangeVolume 20, No. 4 MAGAZINE April 2012 Teaching the Serious Player Stats Reveal What That Golfer Wants Now Also in this issue: • Websites That Work • Get More out of Demo Day • GRAA Awards: How to Enter • Corporate Golf Hideaway TEEINGOFF Page 22 A Demo Day Facelift WWW.GOLFRANGE.ORG APRIL 2012 | GOLF RANGE MAGAZINE | 3 TEEINGOFF Page 26 Where Corporate Golf Lives On WWW.GOLFRANGE.ORG APRIL 2012 | GOLF RANGE MAGAZINE | 5 CONTENTS Golf Range MAGAZINE Volume 20, Number 4 April 2012 Features 20 Business of Teaching: Marketing to the Serious Golfer The high-income, high-frequency golfer who says that score is important to enjoyment of the game is—or could be—a cornerstone of your instruction program By David Gould 22 22 Clubfitting: Making Demo Day More about the Pro Major golf gear brands deliver excitement during Demo Day events, but increasingly they’re turning the spotlight back onto on-site professionals.