Submission DR299

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Horse Breeds 1 List of Horse Breeds

List of horse breeds 1 List of horse breeds This page is a list of horse and pony breeds, and also includes terms used to describe types of horse that are not breeds but are commonly mistaken for breeds. While there is no scientifically accepted definition of the term "breed,"[1] a breed is defined generally as having distinct true-breeding characteristics over a number of generations; its members may be called "purebred". In most cases, bloodlines of horse breeds are recorded with a breed registry. However, in horses, the concept is somewhat flexible, as open stud books are created for developing horse breeds that are not yet fully true-breeding. Registries also are considered the authority as to whether a given breed is listed as Light or saddle horse breeds a "horse" or a "pony". There are also a number of "color breed", sport horse, and gaited horse registries for horses with various phenotypes or other traits, which admit any animal fitting a given set of physical characteristics, even if there is little or no evidence of the trait being a true-breeding characteristic. Other recording entities or specialty organizations may recognize horses from multiple breeds, thus, for the purposes of this article, such animals are classified as a "type" rather than a "breed". The breeds and types listed here are those that already have a Wikipedia article. For a more extensive list, see the List of all horse breeds in DAD-IS. Heavy or draft horse breeds For additional information, see horse breed, horse breeding and the individual articles listed below. -

Clarkes Daylight - Fs Hsh

CLARKES DAYLIGHT - FS HSH Article by Lindsay Ferguson Foundation Sire CLARKES DAYLIGHT - FS HSH ASH Reg: 3390 The mixed farming country near Clifton, in the Darling Downs region of Queensland, has long been the heart of that state’s polo playing and breeding. If you know anything about Queensland polo then you would have heard of their greats such as Stuart Cooke, Marshall Muller, Ron Bell, Jim McGinley and Ken Telford. hen, of course, there is the Gilmore family. It is because kilometres south of Toowoomba. Ken was a master horseman of the Gilmores were often mounted on horses from the the district in those days, and one of Australia’s great polo players T family of CLARKES DAYLIGHT - FS HSH, his siblings of the 1950s and 1960s. In a sport where players are rated with a and his progeny, that many a match was won. handicap from -2 to 10 goals, Ken was one of the few near the top The history of this Foundation Sire revolves largely around his – an ‘8 goal’ player. He travelled widely across the country with the breeder and owner, Eric Clarke. He was a keen horseman, who sport, also spending some time playing in England and New Zealand. died about ten years ago, but we are fortunate to have friends and Ian Glasby, of the Holmrose Stock Horse Stud, also lives in neighbours who know the story of Eric and his horses. Ken Telford the area. He recalls hearing much of the discussion about these was such a friend and neighbour, who lived just across the creek horses as a kid, standing about the chaff-cutter when Eric used to in the tight-knit community of polo people at Clifton, about 40 regularly drop in to pick up his lucerne feed from the Glasbys. -

The Waler Horse -A Unique Australian

THE WALER HORSE -A UNIQUE AUSTRALIAN. ****** AUTHOR: PATRICIA ROBINSON ****** Submitted in partial requirement for the degree of J oumalism and Media Studies at the University of Tasmania. October 2004 1t ~sis . HNSON 1S - )4 G~J rkr~ Ro E.1 ,;\).( oAJ ~.:r.fv\ . s LeoL{- Use of Theses IBIS VOLUME is the property of the University of Tasmania, but the literary rights of the author must be respected. Passages must not be copied or closely paraphrased without the written consent of the author. If the reader obtains any assistance from this volume he/she must give proper credit in his/her own work. This Thesis by ...~ ~ ~! .<;-. ·. ~ .....'?. ,Q. .. ~$'.?.~... .... ........ has been used by the following persons, whose signatures attest their acceptance of the above restrictions. Name Date Name Date ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: Thanks to Lindsay Simpson for her guidance and encouragement. Thanks to Prudence Cotton and Luella Meaburn for welcoming me into their lives, and helping me learn about Walers through their unique Australians - Poppy and Paterson. Thanks also to Walers - Dardanelle and Anzac Parade. I especially thank Jacqui and Ben for allowing me to be part of a Great Adventure. Long may it continue! P.R. OCTOBER 2004 ****** 1 RUNNYMEDE, TASMANIA JUL y 7TH .2004 The Horse-Handler enters the round yard but the wild colt munching hay takes little notice until she removes the remaining hay. That gets his attention and he looks at the Handler suspiciously, out of one eye. She talks to him softly, reassuringly. He is not used to such close contact and reacts nervously. He stands very still and his sides quiver, his breath coming noisily, steaming in the icy Tasmanian air. -

The Australian Stock Horse Society Limited

THE AUSTRALIAN STOCK HORSE SOCIETY LIMITED ABN 35 001 440 437 P O Box 288, SCONE NSW 2337 Phone: 02 6545 1122 Fax: 02 6545 2165 Website: www.ashs.com.au Email: [email protected] Rules and Regulations Contents This document contains the Rules and Regulations of THE AUSTRALIAN STOCK HORSE SOCIETY LIMITED, as approved by the Board of Directors, and is effective from 1st January 2019. Please note that from that time onwards, all prior regulations will be superseded and are null and void. Section 1 - Administration 1. Regulations 2. Definitions Section 2 - Membership 1. Membership Full Membership Participant Membership Temporary Membership Youth Membership Joint Membership Subscriber Membership Life Membership Honorary Membership Honorary Life Membership 2. Privileges for Financial Members 3. Privacy Act Section 3 - Registration of Horses 1. Prior to Breeding Service Agreement Artificial Agreement 2. Breeding Methods Natural Service Artificial Insemination Embryo Transfer Other Breeding Techniques 3. ASH Breeding Certificates 4. Eligibility for ASH Events, Sales and Awards Competition Eligible NOT Competition Eligible 5. Registration of Horses Submitting an Application Registration Status, Eligibility and Procedures Stud Book - Non Foal Recorded Foal Recording (discontinued) Stud Book - Previously Foal Recorded Breeding Purposes Only - ASB (Thoroughbred) First Cross Second Cross Special Merit Exceptional Circumstances Registration for Eligible Horses – Approved by Board 6. Upgrading Registration Breeding Upgrade 7. Prefix Registration 8. Naming of Horses 9. Sire Registration 10. DNA Sample Collection 11. DNA Profiles and Screening Tests ASHS - RULES AND REGULATIONS Section 1 – Administration Effective – 1st January 2019 Page 1 Contents - Continued 12. DNA Anomaly Procedures 13. Disputed Parentage 14. -

2021 Horse Schedule

Schedule Sydney Royal Horse Show 1 - 12 April 2021 Sydney Showground Sydney Olympic Park www.rasnsw.com.au Cover Photo: Josh Barnett Rodeo - Saddle Bronc Horse: Moves Like Jagger owned by Gill Bros Rodeo (Moves Like Jagger is a four time “Australian Champion Saddle Bronc of the Year”) Photographer: Glennys Lilley Welcome from the President With a proud history running competitions for the benefit of breeders, producers and craftspeople going all the way back to 1823, the Royal Agricultural Society of NSW welcomes entries from right across Australia to be judged at the Sydney Royal Easter Show. This year, more than ever before, it is important that our competitions and events draw a community response and demonstrate the strength and commitment of breeders, producers, artisans, competitors and exhibitors. Our competitions are held not only to improve the quality of produce and animal breeds – as per our charter – but also to allow all those who enter the opportunity to take pride in their achievements and present them to an eager and curious audience during the Sydney Royal Easter Show. Your decision to take part in our competitions ensures your place in our history, joining more than 30,000 others each year with a willingness to be judged and assessed, and introduces your entry to Showgoers, consumers, exhibitors and our highly regarded judges. Sydney Royal competitions are constantly evolving, not only due to industry trends but also due to the innovation and enthusiasm of competitors. Our ability to change and adapt guarantee Sydney Royal awards remain relevant and worth striving for. Winning an award in a Sydney Royal competition confirms the exceptional standard of your entry and is an incredible acknowledgement of your hard work and dedication as judged by our esteemed panels of judges. -

Age-Related Changes in the Behaviour of Domestic Horses As Reported by Owners

animals Article Age-Related Changes in the Behaviour of Domestic Horses as Reported by Owners Bibiana Burattini 1,*, Kate Fenner 1 , Ashley Anzulewicz 1, Nicole Romness 1, Jessica McKenzie 2, Bethany Wilson 1 and Paul McGreevy 1 1 Sydney School of Veterinary Science, Faculty of Science, University of Sydney, Camperdown, NSW 2006, Australia; [email protected] (K.F.); [email protected] (A.A.); [email protected] (N.R.); [email protected] (B.W.); [email protected] (P.M.) 2 School of Life and Environmental Sciences, Faculty of Science, University of Sydney, Camperdown, NSW 2006, Australia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +61-409-326-343 Received: 16 November 2020; Accepted: 3 December 2020; Published: 7 December 2020 Simple Summary: Some treatments for common problem behaviours in domestic horses can compromise horse welfare. Such behaviours can be the manifestation of pain, confusion and conflict. In contrast, among the desirable attributes in horses, boldness and independence are two important behavioural traits that affect the fearfulness, assertiveness and sociability of horses when interacting with their environment, objects, conspecifics and humans. Shy and socially dependent horses are generally more difficult to manage and train than their bold and independent counterparts. Previous studies have shown how certain basic temperament traits predict the behavioural output of horses, but few have investigated how the age of the horse and the age it was when started being trained under saddle affect behaviour. Using 1940 responses to the Equine Behaviour Assessment and Research Questionnaire (E-BARQ), the current study explored the behavioural evidence of boldness and independence in horses and how these related to the age of the horse. -

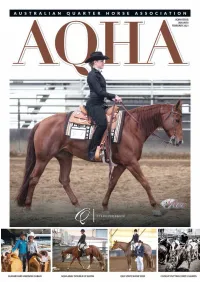

AQHA Jan-Feb 2021 WEB NEW.Pdf

PG.1 JANUARY/FEBRUARY ISSUE 2021 PG.2 AUSTRALIAN QUARTER HORSE ASSOCIATION - WWW.AQHA.COM.AU PG.3 JANUARY/FEBRUARY ISSUE 2021 PG.4 Content ISSUE: JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2021 EVENT: SQHA SRAC DOUBLE UP SHOW Holly Gutterson and Triandibo Super Diva Q-74111 PHOTOGRAPHER: ACE Photography PUBLISHED BY: Australian Quarter Horse Association Lot 13 Jack Smyth Drive, Hillvue Tamworth NSW 2340 T: 02 6762 6444 | F: 02 6762 6422 | www.aqha.com.au ABN: 41 000 964 643 • ISSN: 1832-1704 AQHA STAFF: Manager: Gemma Clarke • [email protected] Advertising Accounts: Melanie Brown • [email protected] and editorial Personal Assistant: Wendy Fahey • [email protected] due the 1st of Reception: Marg Hausfeld •[email protected] each month prior Tamra Clark • [email protected] Vanessa Roach • [email protected] to publication Jo Darcy • [email protected] Aleisha Stafford • [email protected] Jessica Rapley • [email protected] COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Australian Quarter Horse Association 2006. This publication is protected by copyright. Except as EDITORIAL SUBMISSION: permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of the publication may be reproduced in any form with out the prior permission of PEEK Graphics the AQHA or, in the case of material prepared by contributors, the permission of the third-party contributor authors. Reproduction P: 0416 063 204 of this publication in whole or part, without the permission of the copyright owner is prohibited. Requests and inquiries concerning E: [email protected] reproduction must be directed to the General Manager. Publication Disclaimer: The views expressed in the articles and other material contained in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the AQHA or it’s staff. -

This Is a Cross-Reference List for Entering Your Horses at NAN. It Will

This is a cross-reference list for entering your horses at NAN. It will tell you how a breed is classified for NAN so that you can easily find the correct division in which to show your horse. If your breed is designated "other pure," with no division indicated, the NAN committee will use body type and suitability to determine in what division it belongs. Note: For the purposes of NAN, NAMHSA considers breeds that routinely fall at 14.2 hands high or less to be ponies. Stock Breeds American White Horse/Creme Horse (United States) American Mustang (not Spanish) Appaloosa (United States) Appendix Quarter Horse (United States) Australian Stock Horse (Australia) Australian Brumby (Australia) Bashkir Curly (United States, Other) Paint (United States) Quarter Horse (United States) Light Breeds Abyssinian (Ethiopia) Andravida (Greece) Arabian (Arabian Peninsula) Barb (not Spanish) Bulichi (Pakistan) Calabrese (Italy) Canadian Horse (Canada) Djerma (Niger/West Africa) Dongola (West Africa) Hirzai (Pakistan) Iomud (Turkmenistan) Karabair (Uzbekistan) Kathiawari (India) Maremmano (Italy) Marwari (India) Morgan (United States) Moroccan Barb (North Africa) Murghese (Italy) Persian Arabian (Iran) Qatgani (Afghanistan) San Fratello (Italy) Turkoman (Turkmenistan) Unmol (Punjab States/India) Ventasso (Italy) Gaited Breeds Aegidienberger (Germany) American Saddlebred (United States) Boer (aka Boerperd) (South Africa) Deliboz (Azerbaijan) Kentucky Saddle Horse (United States) McCurdy Plantation Horse (United States) Missouri Fox Trotter (United States) -

The Arabian Derivative Horse Standard of Excellence

THE ARABIAN DERIVATIVE HORSE STANDARD OF EXCELLENCE Peter 02 4577 5366 www.ahsa.asn.au JUDGIG I-HAD AUSTRALIA ARABIA DERIVATIVES Arabian Derivatives are judged in-hand according to the defined policy of the Arabian Horse Society of Australia Ltd (AHSA). This policy was established in 1960 STADARD OF EXCELLECE and re-affirmed in 1979, when the term “Arabian Derivative” was adopted. The policy states that these horses will be evaluated by a comparative system in ITRODUCTIO terms of saddle horse qualities which make them suitable as performance or working horses. Specific Arabian characteristics are neither an advantage nor a An Arabian Derivative is a horse derived from Pure Arabian bloodlines and those of disadvantage, but are definitely not to be penalised. another breed. Ideally, the progeny will display desirable characteristics and qualities of Judges are not to discriminate against such features as colour, markings and both the Arabian and the other breed. height. There are seven Arabian Derivative registries in Australia: Horses registered in the Derivative Register will be recognisably different in physical * Anglo-Arabian appearance from Purebred Arabian horses. There is a Standard of Excellence for the * Arabian Pony Purebred Arabian and there is a Standard of Excellence for each of the seven Arabian *Arabian Riding Pony Derivatives. It is the duty of a judge to judge each breed against its own Standard of * Arabian Warmblood Excellence. * Partbred Arabian The best Arabian Derivative must not be judged as the one most closely resembling the * Quarab Purebred Arabian. A judge should see the Arabian Derivative as a horse displaying the * Arabian Stockhorse best characteristics of the other breed that has contributed to its makeup, along with its Arabian qualities. -

Analysis of Breed Effects on Semen Traits in Light Horse, Warmblood, and Draught Horse Breeds

Theriogenology 85 (2016) 1375–1381 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Theriogenology journal homepage: www.theriojournal.com Analysis of breed effects on semen traits in light horse, warmblood, and draught horse breeds Maren Gottschalk a, Harald Sieme b, Gunilla Martinsson c, Ottmar Distl a,* a Institute for Animal Breeding and Genetics, University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover, Hannover, Germany b Unit of Reproductive Medicine–Clinic for Horses, University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover, Hannover, Germany c Lower Saxon National Stud Celle, Celle, Germany article info abstract Article history: In the present study, systematic effects on semen quality traits were investigated in 381 Received 4 May 2015 stallions representing 22 breeds. All stallions were used for AI either at the Lower Saxon Received in revised form 4 September 2015 National Stud Celle or the North Rhine-Westphalian National Stud Warendorf. A total of Accepted 28 November 2015 71,078 fresh semen reports of the years 2001 to 2014 were edited for analysis of gel-free volume, sperm concentration, total number of sperm, progressive motility, and total Keywords: number of progressively motile sperm. Breed differences were studied for warmblood and Stallion light horse breeds of both national studs (model I) and for warmblood breeds and the Semen quality Breed draught horse breed Rhenish German Coldblood from the North Rhine-Westphalian fi Mixed model National stud (model II) using mixed model procedures. The xed effects of age class, Variance year, and month of semen collection had significant influences on all semen traits in both analyses. A significant influence of the horse breed was found for all semen traits but gel- free volume in both statistical models. -

Newcolorcharts2020.Pdf

1 Lesli Kathman Blackberry Lane Press First published in 2018 by Blackberry Lane Press 4700 Lone Tree Ct. Charlotte, NC 28269 blackberrylanepress.com © 2020 Blackberry Lane Press, LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Assessing Color and Breed In model horse competitions, the goal is to faithfully recreate the equestrian world in miniature. It is what exhibitors strive to do and what judges consider when evaluating a table of entries. One aspect of that evaluation is whether the color of the model is realistic. In order to assess this, a judge must be able to distinguish between visually similar (but often geneti- cally distinct) colors and patterns and determine whether or not the color depicted on the model is suitable for the breed the entrant has assigned. This task is complicated by the fact that many participants—who are at heart collectors as well as competitors—are attracted to pieces that are unique or unusual. So how does a judge determine which colors are legitimate for a particular breed and which are questionable or outright unrealistic? When it comes to the range of colors within each breed, there are three basic considerations. Breeds are limited by the genes present in the population (what is possible), by any restrictions placed by their registry (what is permissible), and by what is counted as a fault in breed competitions (what is penalized). -

2019 Epic Horse Sale Terms & Conditions

Midcoast Rural Agencies T/A Ray White Rural Kempsey (ACN 168 016 260) 2019 Epic Horse Sale Terms & Conditions 1. The standard Australian Livestock & Property Agents 4. The owner is responsible for checking that the information Association Ltd (ALPA) terms and conditions for livestock on the horse’s registration certificate is correct at the sale apply to livestock sales made at the Ray White Rural time of nomination, i.e. sex, colour, brands, markings, Kempsey (RWRK) Epic Horse Sale. A copy of the APLA etc. Owners are advised to review the relevant Society’s terms and conditions will be available at the Kempsey (i.e. AQHA, ASHS or EPRA ) regulations relating to Horse branch of RWRK and at the RWRK Epic Horse Sale. Identification obtainable from the relevant Society, in particular the verification of brands and markings 2. All horses offered for sale at the RWRK Epic Horse Sale must policies. A horse would be rejected from the RWRK Epic be either registered Australian Stock Horses or registered Horse Sale under relevant identification Regulations Australian Quarter Horses. We also encourage Vendors to which AQHA, ASHS or EPRA carry due to brand or become members of the Equine Performance Registry of significant marking discrepancy. Horses must be Australia to be eligible for extra incentives. presented to the satisfaction of an appointed RWRK Epic No foal recorded horses will be accepted. Any horses Horse Sale Inspector and may be vet checked prior to sale accepted as a colt cannot be sold as a gelding. Horses must commencement. The inspectors may reject a horse from be registered prior to nominating for sale.