A Qualitative Investigation Into the Active Level of Perception

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Are You What You Watch?

Are You What You Watch? Tracking the Political Divide Through TV Preferences By Johanna Blakley, PhD; Erica Watson-Currie, PhD; Hee-Sung Shin, PhD; Laurie Trotta Valenti, PhD; Camille Saucier, MA; and Heidi Boisvert, PhD About The Norman Lear Center is a nonpartisan research and public policy center that studies the social, political, economic and cultural impact of entertainment on the world. The Lear Center translates its findings into action through testimony, journalism, strategic research and innovative public outreach campaigns. Through scholarship and research; through its conferences, public events and publications; and in its attempts to illuminate and repair the world, the Lear Center works to be at the forefront of discussion and practice in the field. futurePerfect Lab is a creative services agency and think tank exclusively for non-profits, cultural and educational institutions. We harness the power of pop culture for social good. We work in creative partnership with non-profits to engineer their social messages for mass appeal. Using integrated media strategies informed by neuroscience, we design playful experiences and participatory tools that provoke audiences and amplify our clients’ vision for a better future. At the Lear Center’s Media Impact Project, we study the impact of news and entertainment on viewers. Our goal is to prove that media matters, and to improve the quality of media to serve the public good. We partner with media makers and funders to create and conduct program evaluation, develop and test research hypotheses, and publish and promote thought leadership on the role of media in social change. Are You What You Watch? is made possible in part by support from the Pop Culture Collaborative, a philanthropic resource that uses grantmaking, convening, narrative strategy, and research to transform the narrative landscape around people of color, immigrants, refugees, Muslims and Native people – especially those who are women, queer, transgender and/or disabled. -

Get PDF « the Bad Girls Club

K165WGLOKDMW \ Book # The Bad Girls Club The Bad Girls Club Filesize: 9.76 MB Reviews A very great ebook with perfect and lucid answers. It can be packed with wisdom and knowledge I found out this book from my dad and i encouraged this publication to learn. (Elena McLaughlin) DISCLAIMER | DMCA FAEAACB7XO4B > Kindle » The Bad Girls Club THE BAD GIRLS CLUB Bloomsbury Publishing PLC, 2005. Paperback. Book Condition: New. No.1 BESTSELLERS - great prices, friendly customer service â" all orders are dispatched next working day. Read The Bad Girls Club Online Download PDF The Bad Girls Club IDJLDZJCGCKK # Doc « The Bad Girls Club Relevant Books TJ new concept of the Preschool Quality Education Engineering the daily learning book of: new happy learning young children (3-5 years) Intermediate (3)(Chinese Edition) paperback. Book Condition: New. Ship out in 2 business day, And Fast shipping, Free Tracking number will be provided aer the shipment.Paperback. Pub Date :2005-09-01 Publisher: Chinese children before making Reading: All books are the... Download ePub » TJ new concept of the Preschool Quality Education Engineering the daily learning book of: new happy learning young children (2-4 years old) in small classes (3)(Chinese Edition) paperback. Book Condition: New. Ship out in 2 business day, And Fast shipping, Free Tracking number will be provided aer the shipment.Paperback. Pub Date :2005-09-01 Publisher: Chinese children before making Reading: All books are the... Download ePub » The Day I Forgot to Pray Tate Publishing. Paperback. Book Condition: New. Paperback. 28 pages. Dimensions: 8.7in. x 5.8in. -

A VEIL of DEVIANCE: an EXAMINATION of GENDER PERFORMANCE and MEDIA ENGAGEMENT in REALITY TELEVISION a Thesis Presented to the Fa

A VEIL OF DEVIANCE: AN EXAMINATION OF GENDER PERFORMANCE AND MEDIA ENGAGEMENT IN REALITY TELEVISION A Thesis Presented to the faculty of the Department of Sociology California State University, Sacramento Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Sociology by Korin Raquel Vallejo SPRING 2014 A VEIL OF DEVIANCE: AN EXAMINATION OF GENDER PERFORMANCE AND MEDIA ENGAGEMENT IN REALITY TELEVISION A Thesis by Korin Raquel Vallejo Approved by: ______________________________________, Committee Chair Dr. Todd Migliaccio _______________________________________, Second Reader Dr. Kevin Wehr _____________________________ Date ii Student: Korin Raquel Vallejo I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this thesis is suitable for shelving in the Library and credits is to be awarded for the thesis. _____________________________, Graduate Coordinator ____________________ Dr. Amy Lui Date Department of Sociology iii Abstract of A VEIL OF DEVIANCE: AN EXAMINATION OF GENDER PERFORMANCE AND MEDIA ENGAGEMENT IN REALITY TELEVISION by Korin Raquel Vallejo Following Norman K. Denzin’s theory on media message transmittance and audience engagement this study sought to examine the gendered messages being communicated through the reality television program “The Bad Girls Club”. Season four of the show was transcribed in an ethnographic approach; with efforts to fully engulf in the culture and sub-society of “The Bad Girls Club” and with the self-proclaimed deviant women on the program through a social constructionist lens. To grasp media engagement, two public viewings were held in which the researcher played participant observer in order to gage the audiences’ interaction, receipt, and implantation of gendered messages. -

Dean's Report 2015-16

Ursinus College Report of the Dean on Faculty and Student Professional Achievement 2015-2016 Table of Contents Message from the Dean ............................................................................................................. 3 The Professional Achievement of Faculty .................................................................................. 6 Summaries of Departmental Achievement and Activity ........................................................... 6 The William Wilson Baden Faculty Lecture Series .................................................................11 Pre-Tenure Leaves ................................................................................................................12 Sabbatical Leaves .................................................................................................................12 The Professional Achievement of Students ...............................................................................13 Student-Faculty Publications .................................................................................................13 Student Conference Presentations ........................................................................................15 Departmental Honors ............................................................................................................25 Student External Grants, Fellowships, Scholarships, and Distinctions ...................................28 Notable Post-baccalaureate Plans .........................................................................................30 -

Katrina Cooney

Katrina Cooney Casting Experience Top Chef 17 (Bravo) - Magical Elves, 2019 Casting Manager Project Runway 18 (Bravo) - Magical Elves, 2019 Casting Manager Are You The One? Fluid (MTV) - Lighthearted Entertainment, 2019 Casting Manager Project Runway 17 (Bravo) - Magical Elves, 2018 Casting Manager Project Runway 17 (Unaired/No Network) - Bunim/Murray, 2018 Casting Manager MasterChef 9 (FOX) - En demol Shine, 2017-2018 Casting Coordinator Project Runway 16 (Lifetime) - B unim/Murray, 2017 Casting Manager Emmy nominated for “Outstanding Casting For A Reality Program” Project Runway 15 (Lifetime) - B unim/Murray, 2016 Casting Manager Emmy nominated for “Outstanding Casting For A Reality Program” Bad Girls Club 15 (Oxygen) - Bunim/Murray, 2015 Casting Manager Project Runway 14 (Lifetime) - B unim/Murray, 2015 Casting Manager Project Runway 13 (Lifetime) - B unim/Murray, 2014 Casting Manager The Cure (ABC) - Bunim/Murray, 2014 Casting Manager Are You The One? 2 (MTV) - Lighthearted Entertainment, 2014 Casting Manager Dating Naked 2 (Vh1) - L ighthearted Entertainment, 2014 Casting Manager Project Runway 12 (Lifetime) - B unim/Murray, 2013 Casting Manager Don’t Give Up: There’s Always Hope (MTV) - Epic Junction, 2013 Casting Coordinator Project Runway: Under The Gunn (Lifetime) - Bunim/Murray, 2013 Casting Manager Q’Viva (Univision/FOX) - XIX Entertainment, 2012 Talent Coordinator I’m Having Their Baby 2 (Oxygen) - Epic Junction, 2012 Casting Coordinator Stars in Danger (FOX) - Bunim/Murray, 2012 Casting Manager Best Ink 2 (Oxygen) - B unim/Murray, -

52 Nd Stree T Swin G

DORE DeQUATTRO New York City Swing Corp. nd 718.428.7478 52 STREET SWING [email protected] www.nycswing.biz An all-star band that has worked with everyone from all corners and genres of the music industry Our Musicians ALVIN MOODY Music Director, Bass, Vocals Moody has performed, toured, written, produced and worked for various artists including Russell Simmons, the late Whitney Houston, Cher, Patti Labelle, the late Luther Vandross, Gavin DeGraw, Jonathan Butler and the late Phyllis Hyman. VOCALS PERRITA (Vocals) heartedness that continues to (pronounced Pair-ree-ta) overwhelm audiences from Japan to Perrita has traveled around the the Royal Families of Morooco. She world performing with various has had the honor of performing artists and began her musical with great artists: Alexander O'Neal career at the tender age of five by and Cherrelle, Bill Crosby, Siedah playing both the violin and Garrett, Liza Minelli, SOS Band, viola. Her musical education Lonnie Liston Smith, Mickie Howard, included rigorous study of both the Najee, Phoebe Snow, Onaje Allan classical and popular genres. By Gumbs, Adeva, Kool and The Gang, high school, Perrita expanded her and songwriters - Diane Warren interest in musical choirs. And and Desmond Child. One of her under the direction of Mr. Charles latest projects is about to be a Wright, was guided into the world worldwide released album with the of exploring and unleashing her Rock Band - "Rickity". vocal abilities. By graduation, which helped her establish her Perrita was performing around the distinctive style full of explosive PERRITA has that Voice that there is Boston and surrounding areas sound and energetic warm room to hear! DANNI AI (Vocals) MICHELE ZAYLA (Vocals) Danni Ai is a NYC singer/songwriter Michele is a full-time NYC and multimedia designer. -

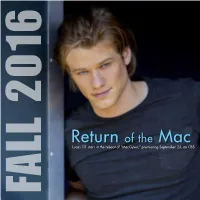

Return of The

Return of the Mac Lucas Till stars in the reboot of “MacGyver,” premiering September 23, on CBS. FALL 2016 FALL “Conviction” ABC Mon., Oct. 3, 10 p.m. PLUG IN TO Right after finishing her two-season run as “Marvel’s Agent Carter,” Hayley Atwell – again sporting a flawless THESE FALL PREMIERES American accent for a British actress – BY JAY BOBBIN returns to ABC as a smart but wayward lawyer and member of a former first family who avoids doing jail time by joining a district attorney (“CSI: NY” alum Eddie Cahill) in his crusade to overturn apparent wrongful convictions … and possibly set things straight with her relatives in the process. “American Housewife” ABC Tues., Oct. 11, 8:30 p.m. Following several seasons of lending reliable support to the stars of “Mike & Molly,” Katy Mixon gets the “Designated Survivor” ABC showcase role in this sitcom, which Wed., Sept. 21, 10 p.m. originally was titled “The Second Fattest If Kiefer Sutherland wanted an effective series follow-up to “24,” he’s found it, based Housewife in Westport” – indicating on the riveting early footage of this drama. The show takes its title from the term used that her character isn’t in step with the for the member of a presidential cabinet who stays behind during the State of the Connecticut town’s largely “perfect” Union Address, should anything happen to the others … and it does here, making female residents, but the sweetly candid Sutherland’s Secretary of Housing and Urban Development the new and immediate wife and mom is boldly content to have chief executive. -

'Assassinated' War Correspondent Marie Colvin, Lawsuit Filed by Her Relatives Claims

Feedback Tuesday, Apr 10th 2018 12AM 64°F 3AM 57°F 5-Day Forecast Home U.K. News Sports U.S. Showbiz Australia Femail Health Science Money Video Travel Columnists DailyMailTV Latest Headlines News World News Arts Headlines Pictures Most read Wires Coupons Login ADVERTISEMENT As low as $0.10 ea STUDENT Ribbon Learn More Assad's forces 'assassinated' Site Web Enter your search renowned war correspondent Marie ADVERTISEMENT Colvin and then celebrated after they learned their rockets had killed her, lawsuit iled by her relatives claims President Bashar Assad's forces targeted Marie Colvin and celebrated her death This is according to a sworn statement a former Syrian intelligence oicer made The 55-year-old Sunday Times reporter died in a rocket attack in Homs By JESSICA GREEN FOR MAILONLINE PUBLISHED: 14:25 EDT, 9 April 2018 | UPDATED: 16:14 EDT, 9 April 2018 65 175 shares View comments Syria President Bashar Assad's forces allegedly targeted veteran war correspondent Marie Colvin and then celebrated after they learned their rockets had killed her. This is according to a sworn statement a former Syrian intelligence oicer made in a wrongful death suit iled by her relatives. The 56-year-old Sunday Times reporter died alongside French photographer Remi Ochlik, 28, in a rocket attack on the besieged city of Homs. ADVERTISING Like +1 Daily Mail Daily Mail Follow Follow @DailyMail Daily Mail Follow Follow @dailymailuk Daily Mail FEMAIL TODAY The intelligence defector, code named EXCLUSIVE: Tristan Ulysses, says Assad's military and Thompson caught on intelligence oicials sought to capture or video locking lips with a brunette at NYC club kill journalists and media activists in just days before Khloe Homs. -

Bad Girls Club Reunion Season 12

Bad girls club reunion season 12 click here to download Pages: 1 2. Bad Girls Clubbad girls club season 12 Sponsored. Black Ink Crew Chicago Season 3 Episode 13 - DDotOmen. Coathanger. 4d. A group of rebellious women are put in a house together in an experiment intended to moderate their behavior. The girls reunite to takes a look back at the present season. | The Bad Girls Club Season Subscribe to AfterBuzz TV's YouTube Channel: www.doorway.ru AFTERBUZZ TV — Bad Girls. Check out my Recap of Part 2 of #BGC12Reunion. Comment & Subscribe Blog: http://darealrastabwoi. BGC12 is over but the Drama continues as they reunite for a 3 part Reunion and its not to be missed. Watch my. Bad Girls Club Season 12 Episode 15 (Reunion Part 1). Mr. World Premiere > Uncategorized > Bad Girls Club Season 12 Episode 15 (Reunion Part 1). Summary: (Reunion Part One): You can watch The Bad Girls Club Season 12 Episode 15 online here at www.doorway.ru Tv Show "The Bad Girls Club". First seen, Breaking Bad Girls. Last seen, Season Reunion Part 3. Appeared "Alex" Rice (also known as The Hot Model) is a original bad girl of Season Watch Bad Girls Club - Season 12, Episode 17 - Reunion Part 3: Conclusion. Dalila gets one last chance to prove herself and a fuming Redd. Watch Bad Girls Club season 12 episode 17 (S12E17) online free (NO SIGN UP) only at TVZion, largest 17 Watch Bad Girls Club S12E17 online - Reunion (3). Buy Bad Girls Club, Season Read 44 Movies & TV Reviews - www.doorway.ru Bad Girls Club 14 Seasons Unsupported Browser . -

Graduation Parties

www.kentuckynewera.com | TV | Wednesday, April 25, 2012 B5 WEDNESDAY PRIMETIME APRIL 25, 2012 N - NEW WAVE M - MEDIACOM S1 - DISH NETWORK S2 - DIRECTV N M 4 PM 4:30 5 PM 5:30 6 PM 6:30 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 12 AM 12:30 1 AM 1:30 S1 S2 WKRN Nashville's Nashville's Nashville's ABC World Nashville's Wheel of The Suburga- Modern Apartment Revenge " Justice" (N) Nashville's :35 News ! Jimmy Kimmel Live !" :05 Extra :35 Law & Order: C.I. :35 Paid (2) (2) [2] 2 2 ABC News 2 !" News 2 !" News 2 !" News !" News 2 !" Fortune !" Middle tory Family 23 (N) !" News 2 !" !" "Reunion" !" Program !" WSMV Channel 4 Channel 4 Channel 4 NBC News Channel 4 Channel 4 OffTheirR- Best Rock Center With Law & Order: S.V.U. Channel 4 :35 Jay Leno Zig gy :35 Late Night J. Fallon :35 Carson :05 Today Show !" (4) [4] 4 4 NBC News !" News !" News 5 !" !" !" News !" ockers (N) Friends (N) Brian Williams !" "Street Revenge" (N) !" News !" Marley, Adam Levine" Jim Gaffigan (N) Daly WTVF News 5 !" Inside News 5 !" CBSNews News Channel 5 !" Survivor: One World Criminal Minds "Self- CSI: Crime Scene News 5 !" :35 David Letterman !" :35 LateLate S Carol :35 Frasier :05 The Nate Berkus (5) (5) [5] 5 5 CBS Edition !" !" (N) !" Fulfilling Prophecy" !" "Zippered" !" Burnett, Phil Keoghan ! Show !" WPSD Dr. Phil !" Local 6 at NBC News Local 6 at Wheel of OffTheirR- Best Rock Center With Law & Order: S.V.U. -

Download 1 File

COMMUNITY Super Sunday: Giants defeat Patriots; Eli earns MVP SPORTS B1 Life continues for Cadiz woman who lost son, sister PENNYRILE B4 WWW.KENTUCKYNEWERA.COM Monday-Tuesday, Feb. 6-7, 2012 | 75 cents, 51 cents average home delivery cost 20 pages, 2 sections | Volume 125, Number 58 | Hopkinsville, Ky. Est. 1869 Wife arrested in soldier’s murder firm the man killed was a soldier. Colorado man also charged He was also able to confirm that neither Jessie Goslyn nor Long are in the Army. in shooting on Fidelio Road However WSMV-TV of Nashville, Tenn., BY ELI PACE being held in the Christian County Jail reports Long was Long NEW ERA EDITOR with no bond on a murder charge. once stationed at Fort Another man, Jerred Tabor Long, Campbell. The wife of a man who was found 24, of Grand Junction, Colo., was ar- Miller also said that Jessie Goslyn shot to death Friday night on a rural rested late Saturday night or early and Long were “acquaintances,” but Christian County road has been Sunday morning in Colorado. He too the circumstances of their relation- charged with his murder. is charged with murder. ship are not entirely clear at this time. Vincent Goslyn Jr., 28, died around Miller confirmed that the two Authorities believe Long participated 8:25 p.m. Friday night after being shot Goslyns were married and Vincent in Vincent Goslyn’s murder and then multiple times while he was in the 400 Goslyn was a soldier at Fort Campbell. drove more than 1,300 miles to Grand block of Fidelio Road, according to Fort Campbell spokesman Rick Junction, Colo., where he was ar- Chris Miller, spokesman for the Chris- Rzepka said Sunday Vincent rested by the Colorado Fugitive Ap- JOHN GODSEY | KENTUCKY NEW ERA tian County Sheriff’s Department. -

Rick Charged with Murder, Arson in Bear Trap Blaze

Mostly sunny High: 60 | Low: 39 | Details, page 2 vs High School All Star Basketball Game June 9th, 2016 • Gogebic Community College Girls Game 5:30pm • Boys Game 7:00pm TICKETS $5 Adults • $2 Students DAILY GLOBE yourdailyglobe.com Tuesday, June 7, 2016 75 cents Rick charged with murder, arson in Bear Trap blaze By RALPH ANSAMI he served for the assault of a unteer Fire Department mem- [email protected] child 13 years ago. bers were already on the scene, HURLEY — A Saxon, Wis., The body of Waldros, 52, of hopelessly battling a blaze that man has been charged with mur- Kimball, was found in the bath- was out of hand. der and arson in the March 12 room area of the structure two The owner of the tavern, T.C. fire that destroyed the Bear Trap days after the fire. An autopsy Henning, the sister of Lisa Wal- Inn in Saxon, resulting in the was performed in Madison as dros, told the deputy her sister death of Lisa Waldros. part of the investigation. had been bartending that night Donald Rick, 44, who resided The complaint says Rick and her car was parked in front on Church Street at the time of entered the Bear Trap with of the building. the fire, is scheduled to appear in intent to steal, while armed with Later that morning, deputy Iron County Court on the a dangerous weapon, intentional- Eric Snow was approached by a charges next Monday at 1:45 ly causing the death of Waldros. Saxon resident, Ray Smith, who p.m.