Legacy Sediment, Lead, and Zinc Storage in Channel and Floodplain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Floodplain Geomorphic Processes and Environmental Impacts of Human Alteration Along Coastal Plain Rivers, Usa

WETLANDS, Vol. 29, No. 2, June 2009, pp. 413–429 ’ 2009, The Society of Wetland Scientists FLOODPLAIN GEOMORPHIC PROCESSES AND ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS OF HUMAN ALTERATION ALONG COASTAL PLAIN RIVERS, USA Cliff R. Hupp1, Aaron R. Pierce2, and Gregory B. Noe1 1U.S. Geological Survey 430 National Center, Reston, Virginia, USA 20192 E-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Biological Sciences, Nicholls State University Thibodaux, Louisiana, USA 70310 Abstract: Human alterations along stream channels and within catchments have affected fluvial geomorphic processes worldwide. Typically these alterations reduce the ecosystem services that functioning floodplains provide; in this paper we are concerned with the sediment and associated material trapping service. Similarly, these alterations may negatively impact the natural ecology of floodplains through reductions in suitable habitats, biodiversity, and nutrient cycling. Dams, stream channelization, and levee/canal construction are common human alterations along Coastal Plain fluvial systems. We use three case studies to illustrate these alterations and their impacts on floodplain geomorphic and ecological processes. They include: 1) dams along the lower Roanoke River, North Carolina, 2) stream channelization in west Tennessee, and 3) multiple impacts including canal and artificial levee construction in the central Atchafalaya Basin, Louisiana. Human alterations typically shift affected streams away from natural dynamic equilibrium where net sediment deposition is, approximately, in balance with net -

Legacy Sediment and PA’S Chesapeake Bay Tributary Strategies an Innovative BMP Proposal

Legacy Sediment and PA’s Chesapeake Bay Tributary Strategies An Innovative BMP Proposal Pennsylvania Tributary Strategy Steering Committee Legacy Sediment Workgroup 2007 Jeffrey Hartranft Bureau of Waterways Engineering Presentation Outline • PA’s Tributary Strategy – A Timeline and Brief History • Linking Policy and Science- Defining Legacy Sediment • The Science • Chesapeake Bay Watershed Model Phase 5.0 • Innovative New BMP and Innovative Uses of Existing BMP’s • Future Considerations and ?’s PA’s Tributary Strategies – A Brief History • 2004 (December) Draft - PA Chesapeake Bay Tributary Strategy Unveiled- “Working Document” • 2005 Public meetings across PA-Strategy Feedback • 2006 PA Creates Chesapeake Bay Tributary Strategy Steering Committee - Stakeholders Specific Workgroups Organized 1) Point Source Workgroup 2) Agriculture Workgroup 3) Stormwater and Development Workgroup 4) Trading Workgroup 5) Legacy Sediment Workgroup – February 2006 PA Legacy Sediment Workgroup PA DEP PA Fish and Boat Commission PA Department of Transportation PA Farm Bureau PA State Association of Township Supervisors US Environmental Protection Agency US Geological Survey Chesapeake Bay Commission Chesapeake Bay Foundation Academia (Franklin and Marshall College, Lafayette College, PSU) Consultants (Landstudies Inc., Aquatic Resources Restoration Co.) Legacy Sediment Definition Generic Definition Legacy Sediment - Sediment that was eroded from upland areas after the arrival of early Colonial settlers and during centuries of intensive land uses; that deposited in valley bottoms along stream corridors, burying pre-settlement streams, floodplains, wetlands, and valley bottoms; and that altered and continues to impair the hydrologic, biologic, aquatic, riparian, and water quality functions of pre-settlement and modern environments. Legacy sediment often accumulated behind ubiquitous low-head mill dams and in their slackwater environments, resulting in thick accumulations of fine-grained sediment that contain significant amounts of nutrients. -

Legacy Sediment: Definitions and Processes of Episodically Produced

Anthropocene 2 (2013) 16–26 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Anthropocene jo urnal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ancene Legacy sediment: Definitions and processes of episodically produced anthropogenic sediment L. Allan James * Geography Department, University of South Carolina, 709 Bull Street, Columbia, SC 29208, USA A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Article history: Extensive anthropogenic terrestrial sedimentary deposits are well recognized in the geologic literature Received 6 February 2013 and are increasingly being referred to as legacy sediment (LS). Definitions of LS are reviewed and a broad Received in revised form 2 April 2013 but explicit definition is recommended based on episodically produced anthropogenic sediment. The Accepted 2 April 2013 phrase is being used in a variety of ways, but primarily in North America to describe post-settlement alluvium overlying older surfaces. The role of humans may be implied by current usage, but this is not Keywords: always clear. The definition of LS should include alluvium and colluvium resulting to a substantial degree Legacy sediment from a range of human-induced disturbances; e.g., vegetation clearance, logging, agriculture, mining, Post-settlement alluvium grazing, or urbanization. Moreover, LS should apply to sediment resulting from anthropogenic episodes Human environmental impacts Geomorphology on other continents and to sediment deposited by earlier episodes of human activities. Rivers Given a broad definition of LS, various types of LS deposits are described followed by a qualitative description of processes governing deposition, preservation, and recruitment. LS is deposited and preserved where sediment delivery (DS) exceeds sediment transport capacity (TC). -

A Summary of Missouri Fishing Regulations 2019

A SummarySummary of Missouri of Fishing Regulations MissouriEffective March 1, 2019 Fishing Regulations Effective March 1, 2019 DAVID STONNER DAVID DAVID STONNER DAVID Contents Sport Fishing in Missouri . .1 Permits: General Information . 2. Purchasing Permits . .3 Missouri Fishing Permits . .4 General Fishing Rules . 6. Game Fish . .8 Nongame Fish . 10 Live Bait . 12. Bullfrogs and Green Frogs . .14 Mussels and Clams . .14 Turtles . .14 Trout Fishing . .16 Reciprocal Fishing Privileges . 21 Illustrated Guide to the Fishes of Missouri . .22 How to Measure a Fish . .27 Special Area Regulations . .28 MO Fishing App . 4. 1 Fish Consumption Advisory . .42 Definitions . .44 Think You Have a Record? . .45 Contact Information . Back cover What’s New for 2019? ◾◾Lessees may no longer fish, hunt, or trap without a permit on the land that they lease . ◾◾Due to federal and state regulations, you are now required to provide a Social Security number to obtain fishing, hunting, and trapping permits . See Page 3 . Sport Fishing in Missouri When it comes to fishing, Missouri has a In Your Hands lot to offer . More than 200 species of fish The information in this live in the Show-Me State, and more than booklet is only a summary of four dozen species offer opportunities for the fishing rules and contains anglers . Seasons are long, and daily limits only those rules that affect are generous . Regulations exist to improve the ordinary sport angler . It and maintain the quality of fishing, ensure is NOT a legal document and that everyone has an equal chance of is subject to revision during catching fish, and protect aquatic resources . -

Mud Creek Watershed Aquatic Ecosystem Restoration Feasibility Study

Mud Creek Watershed Aquatic Ecosystem Restoration Feasibility Study Task 1: Literature Review and Data Search Suffolk County Executive Hon. Steven Bellone Suffolk County Department of Economic Development and Planning 100 Veterans Memorial Highway P.O. Box 6100 Hauppauge, NY 11788-0099 Joanne Minieri Deputy County Executive and Commissioner Division of Planning and Environment Sarah Lansdale, AICP Director Prepared by: Land Use Ecological Services, Inc. 570 Expressway Drive South, Ste. 2F Medford, NY 11763 (T) 631-727-2400 H2M, Inc. Inter-Fluve, Inc. 570 Broad Hollow Road 301 S. Livingston Street, Suite 200 Melville, NY 11747 Madison, WI 53703 (T) 631-756-8000 (T) 608-271-6355 February 26, 2013 Funding for this report was provided under the Suffolk County Water Quality Protection and Restoration Program pursuant to Capital Project # 8710.110 Mud Creek Watershed Aquatic Ecosystem Restoration Feasibility Study Literature Review and Data Search Contents 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 1 2 Site History and Management Practices ................................................................................. 1 3 Site Conditions ........................................................................................................................ 1 3.1 Topography ...................................................................................................................... 1 3.2 Existing Structures and Infrastructure ............................................................................. -

Estimating Volume of Sediment, Nutrient Content

ESTIMATING VOLUME, NUTRIENT CONTENT, AND RATES OF STREAM BANK EROSION OF LEGACY SEDIMENT IN THE PIEDMONT AND VALLEY AND RIDGE PHYSIOGRAPHIC PROVINCES, SOUTHEASTERN AND CENTRAL PA A Report to the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection Submitted January, 2007, and Revised September 13, 2007, by Robert Walter, Ph. D., Dorothy Merritts, Ph. D., and Mike Rahnis, M. Sc. Executive Summary (p. 3) I. Introduction: Sediment and Nutrient Loads to the Chesapeake Bay (p. 7) A. Sediment and nutrient load reduction goals for the Chesapeake Bay (p. 7) B. The Chesapeake Bay Watershed Model (p. 7) C. Legacy sediment: A newly recognized source of sediment and nutrients to the Chesapeake Bay (p. 8) II. Scope and Objectives of this Report (p. 9) A. Scope of this Report (p. 9) B. Objectives of this Report (p. 10) III. Background: Sources and Yields of Sediment to the Chesapeake Bay and the Significance of Legacy Sediment (p. 11) A. Sediment from upland sources (p. 12) B. Sediment sinks and sources in the stream corridor, and processes of bank erosion (p. 12) C. Geomorphology and temporal variability of sediment sources to streams (p. 13) D. Physiography and spatial variability of sediment loads to the Bay (p. 14) E. Legacy sediment as an explanation for anomalously high sediment loads from the Piedmont (p. 14) IV. Legacy Sediment: Definition, Origin, and Historic Accumulation (p. 15) A. Definition and origin of legacy sediment (p. 15) B. Dams, races, mills, and reservoir sedimentation (p. 16) C. Characteristics of streams with legacy sediment (p. 18) D. Causes of remobilization of legacy sediment and processes of erosion (p. -

The Pennsylvania State University the Graduate School College Of

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Agricultural Sciences BIOGEOCHEMICAL CYCLING OF NITROGEN THROUGH A LANDSCAPE RICH IN LEGACY SEDIMENTS A Thesis in Soil Science by Julie N. Weitzman © 2011 Julie N. Weitzman Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science May 2011 The thesis of Julie N. Weitzman was reviewed and approved* by the following: Jason P. Kaye Assistant Professor of Soil Biogeochemistry Thesis Adviser Michael N. Gooseff Assistant Professor of Civil Engineering Richard C. Stehouwer Associate Professor of Environmental Soil Science David M. Sylvia Professor of Soil Microbiology Head of the Department of Crop and Soil Sciences *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. ii ABSTRACT Sedimentation rates, anoxic conditions, and eutrophication have all increased in the Chesapeake Bay since the time of European settlement. Legacy sediments, deposited during the historic, post-settlement period marked by deforestation, land clearing, and plowing of uplands and valley slopes, act as a significant non-point source of nitrogen to the Bay. At Big Spring Run in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, these legacy sediments now overlay a buried hydric soil, which affects the contemporary transfer of nitrogen from uplands to streams. Recent research suggests that nitrogen transfer to streams is also affected by soil drying and rewetting. Climate change models predict that the variability and magnitude of precipitation events will increase over time. Such changes could lead to extended periods of droughts, followed by increased precipitation. These dry-rewet cycles can alter the structure and activity of soil microbial communities, impacting nutrient retention and release. -

Effects of Legacy Sediment Removal on Nutrients and Sediment in Big Spring Run, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 2009–15

Prepared in cooperation with the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, and in collaboration with Franklin and Marshall College and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Effects of Legacy Sediment Removal on Nutrients and Sediment in Big Spring Run, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 2009–15 Scientific Investigations Report 2020–5031 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Effects of Legacy Sediment Removal on Nutrients and Sediment in Big Spring Run, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 2009–15 By Michael J. Langland, Joseph W. Duris, Tammy M. Zimmerman, and Jeffrey J. Chaplin Prepared in cooperation with the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, and in collaboration with Franklin and Marshall College and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Scientific Investigations Report 2020–5031 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DAVID BERNHARDT, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey James F. Reilly II, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2020 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. Permission to reproduce copyrighted items must be secured from the copyright owner. -

Stream Bank Legacy Sediment Contributions

STREAM BANK LEGACY SEDIMENT CONTRIBUTIONS TO SUSPENDED SEDIMENT AND NUTRIENT EXPORTS FROM A MID-ATLANTIC, PIEDMONT WATERSHED by Grant Jiang A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Water Science and Policy Summer 2019 © 2019 Grant Jiang All Rights Reserved STREAM BANK LEGACY SEDIMENT CONTRIBUTIONS TO SUSPENDED SEDIMENT AND NUTRIENT EXPORTS FROM A MID-ATLANTIC, PIEDMONT WATERSHED by Grant Jiang Approved: __________________________________________________________ Shreeram P. Inamdar, Ph.D. Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: __________________________________________________________ Shreeram P. Inamdar, Ph.D. Director of the Graduate Program in Water Science and Policy Approved: __________________________________________________________ Mark W. Rieger, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources Approved: __________________________________________________________ Douglas J. Doren, Ph.D. Interim Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Shreeram Inamdar for the support, guidance, and advice he has provided over the course of my Master’s degree. I would further like to thank Dr. Jinjun Kan and Dr. Carmine Balascio for their technical expertise and contributions to this project. This project would not have been possible without material support from the Fair Hill Natural Resources Management Area staff, the Delaware Environmental Observing System, the University of Delaware Soils Testing Lab, and the University of Maryland Central Appalachian Stable Isotopes Facility; nor without financial support from the US Department of Agriculture (USDA-NIFA 2017- 67019-26330). Lastly, a heartfelt thank you to my laboratory group (Alyssa Lutgen, Katie Mattern, Nathan Sienkiewicz, Daniel Warner, and Evan Lewis) and my friends for their support. -

Sediment Production in a Coastal Watershed: Legacy, Land Use, Recovery, and Rehabilitation1

Sediment Production in a Coastal Watershed: Legacy, Land Use, Recovery, 1 and Rehabilitation Elizabeth T. Keppeler2 Abstract Sediment production has been measured for nearly half a century at the Caspar Creek Experimental Watersheds. Examination of this sediment record provides insights into the relative magnitudes and durations of sediment production from management practices including road construction, selection harvest and tractor skidding, and later road- decommissioning. The 424-ha South Fork was harvested under standards that applied before passage of the 1973 Forest Practice Act. Regression analysis of annual suspended sediment loads on peak flows indicates that sediment production roughly doubled, with a return to pre- treatment levels about 11 years after harvest ended. However, sediment production again increased in the 1990s as road crossings deteriorated in response to large storms. Road crossings decommissioned in 1998 eroded a volume equivalent to more than half of the total yield in 1999 and enlarged another 20 percent over the last decade. Suspended sediment yields since decommissioning were reduced only for small storms. Recent assessment of 1970’s era roads and skid trails found 443 remaining stream and swale crossings. Stream crossing have eroded an average volume of 10 m3. Stream diversions are common, and many sites have the potential for future diversion. Diversions along incised roads and skid trails contribute to episodic sediment inputs. Mainstem sediment loads are elevated relative to those at tributary gages located above the decommissioned riparian haul road, indicating that sediment yields at the weir are enhanced along the mainstem itself. Since turbidity monitoring began in 1996, South Fork mainstem turbidities have exceeded ecosystem thresholds of concern a higher percentage of time than those in the North Fork. -

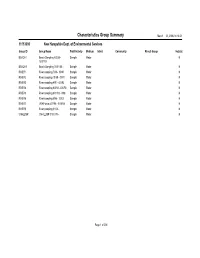

Characteristics Group Summary March 20, 2006 14:16:01

Characteristics Group Summary March 20, 2006 14:16:01 11113300 New Hampshire Dept. of Environmental Services Group ID Group Name Field Activity Medium Intent Community Result Group Habitat BEACH1 Beach Sampling 6/3/85- Sample Water N 12/31/04 BEACH2 Beach Sampling 01/01/05 - Sample Water N RIVER1 River sampling 7/89 - 10/89 Sample Water N RIVER2 River sampling 10/89 - 03/91 Sample Water N RIVER3 River sampling 4/91 - 6/2/92 Sample Water N RIVER4 River sampling 6/3/92- 4/30/93 Sample Water N RIVER5 River sampling 5/01/93 - 4/98 Sample Water N RIVER6 River sampling 5/98 - 12/03 Sample Water N RIVER7 VRAP data 8/27/98 - 9/16/98 Sample Water N RIVER8 River sampling 01/04 - Sample Water N UNHLLMP UNH LLMP 01/01/79 - Sample Water N Page 1 of 200 Characteristics Group Summary March 20, 2006 14:16:01 1111REG1 USEPA, Region I Group ID Group Name Field Activity Medium Intent Community Result Group Habitat BACT001 Routine Bacteria Study Sample Biological Taxon Abundance Bacteria/Virus Multi-Taxon Population Census N BACT002 Toxicity Testing Sample Biological Taxon Abundance Mammals Multi-Taxon Population Census N BASICWQ Basic Water Quality Sampling Field Msr/Obs Water N CHARL98 Baseline Water Quality Study Sample Water N CONT001 Continuous Monitoring Data Data Logger Water N Page 2 of 200 Characteristics Group Summary March 20, 2006 14:16:01 1117MBR US EPA Region 7 Group ID Group Name Field Activity Medium Intent Community Result Group Habitat AAQUAVEG aquatic veg group trial Sample Biological Taxon Abundance Aquatic Vegetation Multi-Taxon Population -

Sediment Contributions from Floodplains and Legacy Sediments To

Geomorphology 235 (2015) 88–105 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Geomorphology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/geomorph Sediment contributions from floodplains and legacy sediments to Piedmont streams of Baltimore County, Maryland Mitchell Donovan a,⁎, Andrew Miller a, Matthew Baker a, Allen Gellis b a University of Maryland-Baltimore County, 1000 Hilltop Circle, Baltimore, MD 21250, USA b U.S. Geological Survey, 5522 Research Park Drive, Baltimore, MD 21228, USA article info abstract Article history: Disparity between watershed erosion rates and downstream sediment delivery has remained an important Received 25 July 2014 theme in geomorphology for many decades, with the role of floodplains in sediment storage as a common Received in revised form 19 January 2015 focus. In the Piedmont Province of the eastern USA, upland deforestation and agricultural land use following Accepted 23 January 2015 European settlement led to accumulation of thick packages of overbank sediment in valley bottoms, Available online 3 February 2015 commonly referred to as legacy deposits. Previous authors have argued that legacy deposits represent a poten- Keywords: tially important source of modern sediment loads following remobilization by lateral migration and progressive Fluvial channel widening. This paper seeks to quantify (1) rates of sediment remobilization from Baltimore County Change detection floodplains by channel migration and bank erosion, (2) proportions of streambank sediment derived from legacy Bank erosion deposits, and (3) potential contribution of net streambank erosion and legacy sediments to downstream Legacy sediment sediment yield within the Mid-Atlantic Piedmont. Floodplain We calculated measurable gross erosion and deposition rates within the fluvial corridor along 40 valley segments from 18 watersheds with drainage areas between 0.18 and 155 km2 in Baltimore County, Maryland.