Alexander Briger and the Australian World Orchestra | the Saturday Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alexander Briger: What Makes a Conductor Is Personality

Alexander Briger: What Makes a Conductor is Personality The Australian conductor tells us about growing up in a musical clan, founding the Australian World Orchestra, and reducing the work load to better enjoy performances and time with his young family. by Jo Litson, 16 May 2019 The Australian conductor tells us about growing up in a musical clan, founding the Australian World Orchestra, and reducing the work load to better enjoy performances and time with his young family. Was there lots of music around you when you were growing up? Yeah, a lot. My mother was a ballet dancer. My uncle Alastair [Mackerras] who lived downstairs was the Headmaster of Sydney Grammar, and he would drive me to school. He was a classical music fanatic. He owned thousands and thousands of CDs, from A to Z, and he was so methodical about it. So, I learnt a hell of a lot of music. Alexander Briger. Photo © Cameron Grayson What instrument did you play? I played violin but I didn’t really take it all that seriously, I have to say. I was much more into aeroplanes, that sort of thing. My uncle was Charles Mackerras, although I didn’t really know him well, he didn’t live here. He would come home to conduct the Sydney Symphony or the opera occasionally. I remember when I was 12, I was taken to a concert that he gave, Mahler’s Fourth Symphony with the Sydney Symphony, and that was the first concert that I was allowed to go to. I remember just being completely blown away by it and that’s when I started to take music very seriously and to think about conducting. -

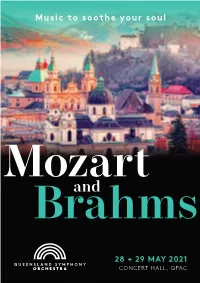

Mozart and Brahms I Contents Welcome 1

Music to soothe your soul Mozartand Brahms 28 + 29 MAY 2021 CONCERT HALL, QPAC PROGRAM | MOZART AND BRAHMS I CONTENTS WELCOME 1 IF YOU'RE NEW TO THE ORCHESTRA 2 FOR YOUNGER EARS 4 DEFINTION OF TERMS 8 LISTENING GUIDE 10 ARTIST BIOGRAPHIES 14 SUPPORTING YOUR ORCHESTRA 24 MUSICIANS AND MANAGEMENT 26 II PROGRAM | MOZART AND BRAHMS WELCOME Today we are very privileged to welcome back to the QPAC stage one of the world's greatest oboists - Diana Doherty. The oboe is a notoriously tricky instrument with several parameters that make it hard to master, none more so than the temperamental double reed at the top. These are hand- made by the oboist from a weed similar to bamboo (Arundo Donax for those playing at home). There are but a handful of oboists in the world who are invited to perform as soloists outside of their country, and Diana is one of them. One of my first trips to see the Sydney Symphony Orchestra as a teenager was to witness Diana perform the Richard Strauss Oboe Concerto. I marvelled at her gloriously resonant oboe sound, especially as she was 37 weeks pregnant! Nearly a decade later I watched Diana premiere Ross Edwards' Oboe Concerto, dressed (as instructed by the composer) as a wild bird, whilst undertaking dance choreography. I can’t think of any other oboist in the world who can pull off these jaw-dropping feats. Today, Diana performs the most famous work from the oboe repertoire - Mozart's Oboe Concerto in C. Diana is one of those oboists who makes the instrument sound like a human voice, and I have no doubt that you will enjoy her breathtaking rendition of this charming yet virtuosic concerto. -

BRITISH and COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS from the NINETEENTH CENTURY to the PRESENT Sir Edward Elgar

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934) Born in Broadheath, Worcestershire, Elgar was the son of a music shop owner and received only private musical instruction. Despite this he is arguably England’s greatest composer some of whose orchestral music has traveled around the world more than any of his compatriots. In addition to the Conceros, his 3 Symphonies and Enigma Variations are his other orchestral masterpieces. His many other works for orchestra, including the Pomp and Circumstance Marches, Falstaff and Cockaigne Overture have been recorded numerous times. He was appointed Master of the King’s Musick in 1924. Piano Concerto (arranged by Robert Walker from sketches, drafts and recordings) (1913/2004) David Owen Norris (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/BBC Concert Orchestra ( + Four Songs {orch. Haydn Wood}, Adieu, So Many True Princesses, Spanish Serenade, The Immortal Legions and Collins: Elegy in Memory of Edward Elgar) DUTTON EPOCH CDLX 7148 (2005) Violin Concerto in B minor, Op. 61 (1909-10) Salvatore Accardo (violin)/Richard Hickox/London Symphony Orchestra ( + Walton: Violin Concerto) BRILLIANT CLASSICS 9173 (2010) (original CD release: COLLINS CLASSICS COL 1338-2) (1992) Hugh Bean (violin)/Sir Charles Groves/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Violin Sonata, Piano Quintet, String Quartet, Concert Allegro and Serenade) CLASSICS FOR PLEASURE CDCFP 585908-2 (2 CDs) (2004) (original LP release: HMV ASD2883) (1973) -

LEOŠ JANÁČEK Born July 3, 1854 in Hukvaldy, Moravia, Czechoslovakia; Died August 12, 1928 in Ostrava

LEOŠ JANÁČEK Born July 3, 1854 in Hukvaldy, Moravia, Czechoslovakia; died August 12, 1928 in Ostrava Taras Bulba, Rhapsody for Orchestra (1915-1918) PREMIERE OF WORK: Brno, October 9, 1921 Brno National Theater Orchestra František Neumann, conductor APPROXIMATE DURATION: 23 minutes INSTRUMENTATION: piccolo, three flutes, two oboes, English horn, E-flat and two B-flat clarinets, three bassoons, contrabassoon, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, harp, organ and strings By 1914, the Habsburg dynasty had ruled central Europe for over six centuries. Rudolf I of Switzerland, the first of the Habsburgs, confiscated Austria and much surrounding territory in 1276, made them hereditary family possessions in 1282, and, largely through shrewd marriages with far-flung royal families, the Habsburgs thereafter gained control over a vast empire that at one time stretched from the Low Countries to the Philippines and from Spain to Hungary. By the mid-19th century, following the geo-political upheavals of the Napoleonic Wars, the Habsburg dominions had shrunk to the present territories of Austria, Hungary, Czech Republic and Slovakia, a considerable reduction from earlier times but still a huge expanse of land encompassing a great diversity of national characteristics. The eastern countries continued to be dissatisfied with their domination by the Viennese monarchy, however, and the central fact of the history of Hungary and the Czech lands during the 19th century was their striving toward independence from the Habsburgs. The Dual Monarchy of 1867 allowed the eastern lands a degree of autonomy, but ultimate political and fiscal authority still rested with Emperor Franz Joseph and his court in Vienna. -

Decca Classics Will Release the Recording of Janáček's Glagolitic

Czech Philharmonic recordings JANÁČEK: GLAGOLITIC MASS Jiří Bělohlávek, conductor Release date: Friday 31 August 2018 (4834080) On 31 August, Decca Classics will release the Czech Philharmonic's recording of Janáček's Glagolitic Mass, Sinfonietta, Taras Bulba and The Fiddler’s Child conducted by the late Jiří Bělohlávek. With the release of Smetana’s Má vlast (My Homeland) at the beginning of the year, the recordings mark some of the last that Bělohlávek made with the Orchestra for Decca Classics. 90 years since Janáček’s death in 1928, the Czech Philharmonic continues to champion the music of its homeland as it has done since its inaugural concert in 1896 when it gave the première of Dvořák's Biblical Songs conducted by the composer. Of the works featured on this release, Janáček's The Fiddler's Child and Sinfonietta both received their world premières from the Czech Philharmonic, the former under Otakar Ostrčil in 1917 and the latter under Václav Talich in 1926. Talich also conducted the Czech Philharmonic in the Prague première of Taras Bulba in 1924. The Orchestra made earlier recordings of the Glagolitic Mass with Karel Ančerl, Václav Neumann and Sir Charles Mackerras, but this is the first under Jiří Bělohlávek who chose to conduct the work at the First Night of the 2011 BBC Proms. Jiří Bělohlávek's recordings with the Czech Philharmonic for Decca Classics include Dvořák’s complete Symphonies & Concertos, Slavonic Dances and Stabat Mater, which was chosen as Album of the Week by The Sunday Times. Under its new Chief Conductor and Music Director, Semyon Bychkov, the Orchestra have recently embarked on The Tchaikovsky Project – recordings of the complete symphonies, the three piano concertos, Romeo & Juliet, Serenade for Strings and Francesca da Rimini. -

PROGRAM NOTES Leoš Janáček – Taras Bulba, Rhapsody

PROGRAM NOTES Leoš Janáček – Taras Bulba, Rhapsody for Orchestra Leoš Janáček Born July 3, 1854, Hochwald (Hukvaldy), Northern Moravia. Died August 12, 1928, Moravska Ostravá, Czechoslovakia. Taras Bulba, Rhapsody for Orchestra Leoš Janáček loved all things Russian. He formed a Russian Club in Brno in 1897, visited Russia twice in the early years of the twentieth century, and even sent his children to Saint Petersburg to study. Of the Russian writers he admired, including Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, it was the novelist and playwright Nikolai Gogol he loved most. Janáček considered writing music based on Gogol's tale of Taras Bulba as early as 1905, although a decade passed before he started work on it. He completed the score three years later, the day before his sixty-first birthday. Still, Taras Bulba is one of Janáček's "early" compositions. Taras Bulba is Janáček's first significant orchestral work. Like Jenůfa, which was premiered in 1904 but didn't come to attention in the larger music world until it was staged in Prague in 1916, Taras Bulba would wait to find its audience. When it was finally performed for the first time in January 1924, Janácek left the hall as soon as the piece was over (the concert was billed as an early observance of his seventieth birthday and he didn't want to celebrate until the actual day arrived) and he failed to hear the enthusiastic crowd calling for him. The violent, bloody story of Taras Bulba is one of Gogol's most enduring and influential works. Ernest Hemingway called it "one of the ten greatest books of all time" (although Vladimir Nabokov, normally a Gogol admirer, likened it to "rollicking yarns about lumberjacks"). -

Concerts with the London Philharmonic Orchestra for Seasons 1946-47 to 2006-07 Last Updated April 2007

Artistic Director NEVILLE CREED President SIR ROGER NORRINGTON Patron HRH PRINCESS ALEXANDRA Concerts with the London Philharmonic Orchestra For Seasons 1946-47 To 2006-07 Last updated April 2007 From 1946-47 until April 1951, unless stated otherwise, all concerts were given in the Royal Albert Hall. From May 1951 onwards, unless stated otherwise, all concerts were given in The Royal Festival Hall. 1946-47 May 15 Victor De Sabata, The London Philharmonic Orchestra (First Appearance), Isobel Baillie, Eugenia Zareska, Parry Jones, Harold Williams, Beethoven: Symphony 8 ; Symphony 9 (Choral) May 29 Karl Rankl, Members Of The London Philharmonic Orchestra, Kirsten Flagstad, Joan Cross, Norman Walker Wagner: The Valkyrie Act 3 - Complete; Funeral March And Closing Scene - Gotterdammerung 1947-48 October 12 (Royal Opera House) Ernest Ansermet, The London Philharmonic Orchestra, Clara Haskil Haydn: Symphony 92 (Oxford); Mozart: Piano Concerto 9; Vaughan Williams: Fantasia On A Theme Of Thomas Tallis; Stravinsky: Symphony Of Psalms November 13 Bruno Walter, The London Philharmonic Orchestra, Isobel Baillie, Kathleen Ferrier, Heddle Nash, William Parsons Bruckner: Te Deum; Beethoven: Symphony 9 (Choral) December 11 Frederic Jackson, The London Philharmonic Orchestra, Ceinwen Rowlands, Mary Jarred, Henry Wendon, William Parsons, Handel: Messiah Jackson Conducted Messiah Annually From 1947 To 1964. His Other Performances Have Been Omitted. February 5 Sir Adrian Boult, The London Philharmonic Orchestra, Joan Hammond, Mary Chafer, Eugenia Zareska, -

Tasmania Discovery Orchestra 2011 Concert 1

Tasmania Discovery Orchestra 2011 The Discovery Series, Season II Concert 1: Discover the Orchestra Alex Briger – Conductor Mozart Overture Die Zauberflöte , K. 620 Beethoven Symphony No. 7 in A Major, Op. 92 Coffee and Cake in the foyer with musicians and conductor Sunday 17 h April 2011 | 2:30pm Stanley Burbury Theatre Sandy Bay, Hobart The Tasmania Discovery Orchestra The TDO is a refreshingly new, bold idea in Australian orchestral music making, designed to offer musicians with advanced orchestral instrument skills the opportunity to come together and make great music in Hobart, Tasmania. The TDO was created in 2010, and was an immediate success, drawing musicians from around Australia to Hobart for the inaugural performance. The response for more performance opportunities for orchestral players is evident by the large number of TDO applicants for both the 2010 and 2011 seasons. This demand led to the creation of another new initiative by the Conservatorium of Music, the TDO Sinfonietta , which will be continuing in 2011. This ensemble performs the chamber music repertoire of the 20th- Century and works composed for mixed orchestral ensemble. With a repertoire of known favourites, this ensemble of more intimate proportions than the TDO, is designed for orchestral musicians with advanced chamber instrumental skills. The TDO and TDO Sinfonietta are about investing in the future of Australian music. Our mission is simple: Australian orchestral musicians, not employed in full-time positions with orchestras, need more opportunities to perform. We want our community and audience to get involved! Have you ever wondered how an orchestra works? Or, perhaps, you’ve always wanted to know what the Conductor does. -

By Leos Janacek: a *Transcription for Wind Symphony

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2005 "Taras Bulba" by Leos Janacek: A *transcription for wind symphony Beth Anne Lynch Duerden University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Duerden, Beth Anne Lynch, ""Taras Bulba" by Leos Janacek: A *transcription for wind symphony" (2005). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 2629. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/owl5-4aku This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy subm itted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. -

The Turn of the Screw

OPÉRA DE BENJAMIN BRITTEN THE TURN OF THE SCREW VENDREDI 12 MARS 2021 À 19 H 30 — CONSERVATOIRE DE PARIS ALEXANDER BRIGER DIRECTION MUSICALE ORCHESTRE DU CONSERVATOIRE DE PARIS BRIGITTE JAQUES-WAJEMAN MISE EN SCÈNE CONSERVATOIRE NATIONAL SUPÉRIEUR DE MUSIQUE ET DE DANSE DE PAR I S RETRANSMISSION EN DIRECT VENDREDI 12 MARS 2021 — 19 H 30 www.conservatoiredeparis.fr SALLE RÉMY-PFLIMLIN DURÉE ESTIMÉE 1 H 45 SANS ENTRACTE Coproduction Conservatoire de Paris et Cité de la musique – Philharmonie de Paris en partenariat avec le CRR de Paris/ Nous remercions l’Opéra national de Paris et la Comédie-Française pour le prêt gracieux de costumes et d’accessoires. photographies : Ferrante Ferranti conception graphique : Mioï Lombard THE TURN OF THE SCREW MUSIQUE DE BENJAMIN BRITTEN LIVRET DE MYFANWY PIPER Une fois par an, le Conservatoire de Paris propose, avec la Philharmonie de Paris, une grande production lyrique qui rassemble tous les talents de l’école. Dirigés par des grands noms de la scène internationale de l’opéra, pour la direction musicale comme pour la mise en scène, ils abordent tous les aspects du processus de création, dans des conditions professionnelles. L’orchestre et les étudiants des classes de chant du Conservatoire de Paris donnent l’opéra de chambre The Turn of the Screw, composé en 1954 pour la Biennale de Venise par Britten. « La cérémonie de l’innocence est noyée », chantent Miss Jessel et Peter Quint, morts dans des conditions mystérieuses, et qui hantent maintenant le manoir où Flora et Miles sont envoyés avec leur nouvelle gouvernante. Fondé sur une nouvelle fantastique d’Henry James datant de la toute fin du XIXe siècle, l’opéra de Britten est dirigé par Alexander Briger, familier de ce répertoire (il a notamment dirigé en Australie, dont il est originaire, The Rape of Lucretia et A Midsummer Night’s Dream, dans une mise en scène de Baz Luhrmann), et que les Parisiens connaissent pour l’avoir apprécié dans les opéras de John Adams, Nixon in China et I Was Looking at the Ceiling and Then I Saw the Sky au Théâtre du Châtelet. -

Le Tour D'écrou

SALLE RÉMY PFIMLIN – CONSERVATOIRE DE PARIS Vendr edi 12 mar s 2021 – 19h30 Le Tour d’écrou Orchestre et étudiants du département des disciplines vocales du Conservatoire de Paris Maîtrise de Paris Alexander Briger Brigitte Jaques-Wajeman CONCERT FILMÉ Concert diffusé le 12 mars 2021 à 19h30 sur conservatoiredeparis.fr où il restera disponible pendant 6 mois et sur Philharmonie Live où il restera disponible pendant 4 mois. Concert également diffusé sur les pages Facebook du Conservatoire national supérieur de musique de Paris et de la Philharmonie de Paris. Programme PROLOGUE P. 6 SYNOPSIS P. 7 BENJAMIN BRITTEN ET LA MUSIQUE DU TEXTE, OU LES ENJEUX D’UNE NOUVELLE TRANSFORMÉE P. 10 SYNOPSIS – D’APRÈS FLORA ET MILES P. 12 AMBIGUÏTÉ D’INTERPRÉTATION ET DUALITÉ DES PERSONNAGES P. 16 SYNOPSIS – D’APRÈS PETER QUINT P. 18 UNE INQUIÉTANTE ÉTRANGETÉ : ENTRETIEN AVEC BRIGITTE JAQUES-WAJEMAN P. 20 SYNOPSIS – D’APRÈS LA GOUVERNANT P. 23 BENJAMIN BRITTEN ET LA FRACTURE DES CODES DE L’OPÉRA TRADITIONNEL : ENTRETIEN AVEC ALEXANDER BRIGE P. 25 LE COMPOSITEUR P. 30 L’ÉQUIPE ARTISTIQUE P. 32 Programme Benjamin Britten Le Tour d’écrou Orchestre du Conservatoire de Paris Étudiants du département des disciplines vocales du Conservatoire de Paris CRR de Paris Thomas Ricart, ténor (le Prologue) Clarisse Dalles, soprano (la Gouvernante) Lucie Peyramaure, soprano (Mrs Grose) Parveen Savart, mezzo-soprano (Miss Jessel) Léo Vermot Desroches, ténor (Peter Quint) Clélia Horvat et Bérénice Arru, sopranos (Flora, en alternance) Robinson Hallensleben et Émile Grizzo, sopranos (Miles, en alternance) Alexander Briger, direction Antoine Petit-Dutaillis, chef assistant Brigitte Jaques-Wajeman, mise en scène Raphaëlle Blin, assistante mise en scène Grégoire Faucheux, scénographie Nicolas Faucheux, création lumières Pascale Robin, création costumes Catherine Saint-Sever, création coiffures et maquillages Coproduction Conservatoire national supérieur de musique et de danse de Paris, Conservatoire à rayonnement régional de Paris, Philharmonie de Paris. -

Shostakovich: Cello Concerto No 2 & Britten: Cello Symphony

Shostakovich Cello Concerto No. 2 Britten Cello Symphony Dmitri Shostakovich (1906 - 1975) Concerto for Cello and Orchestra No. 2 in G, Op. 126 1.Largo [14.39] 2. Allegretto [4.32] 3. Allegretto [15.41] Benjamin Britten (1913 - 1976) Symphony for Cello and Orchestra, Op. 68 4. Allegro maestoso [13.10] 5. Presto inquieto [3.55] 6. Adagio [9.43] 7. Passacaglia: Andante allegro [7.48] Total Timings [69.33] Jamie Walton cello Philharmonia Orchestra Alexander Briger conductor www.signumrecords.com Shostakovich’s Second Cello Concerto and the apparent condescension from an older Britten’s Cello Symphony make the most likely of generation of British composers, excoriated them bedfellows. These works were written by composers as, ‘the “eminent English Renaissance” composers who were pretty much direct contemporaries, who, sniggering in the stalls…There is more in a single in their own ways, and within utterly different page of his Macbeth than in the whole of their political climates, composed in an approachable “elegant” output.’ Around this time, Shostakovich’s manner which could speak not only to their own occasional influence can be spotted in a number of homeland, but to the world at large. Both were Britten’s works, including the Sinfonia da Requiem catapulted into the international limelight as and Britten continued to be fascinated by young men (age 27 in Shostakovich’s case, 31 in Shostakovich’s major works over the years, issuing a Britten’s) by virtue of the phenomenal success of heartfelt and warm tribute on the occasion of the full scale, serious and surprisingly mature operas latter’s 60th birthday.