The New State Quarter Afield with Ranger Mac Coining Wisconsin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SEIU), LOCAL 1, Case No

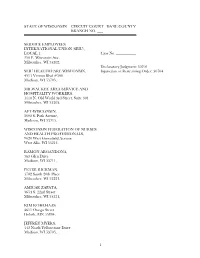

STATE OF WISCONSIN CIRCUIT COURT DANE COUNTY BRANCH NO. ___ SERVICE EMPLOYEES INTERNATIONAL UNION (SEIU), LOCAL 1, Case No. __________ 250 E. Wisconsin Ave, Milwaukee, WI 53202, Declaratory Judgment: 30701 SEIU HEALTHCARE WISCONSIN, Injunction or Restraining Order: 30704 4513 Vernon Blvd #300 Madison, WI 53705, MILWAUKEE AREA SERVICE AND HOSPITALITY WORKERS, 1110 N. Old World 3rd Street, Suite 304 Milwaukee, WI 53203, AFT-WISCONSIN, 1602 S. Park Avenue, Madison, WI 53715, WISCONSIN FEDERATION OF NURSES AND HEALTH PROFESSIONALS, 9620 West Greenfield Avenue, West Allis, WI 53214, RAMON ARGANDONA, 563 Glen Drive Madison, WI 53711, PETER RICKMAN, 3702 South 20th Place Milwaukee, WI 53221, AMICAR ZAPATA, 3654 S. 22nd Street Milwaukee, WI 53221, KIM KOHLHAAS, 4611 Otsego Street Duluth, MN 55804, JEFFREY MYERS, 342 North Yellowstone Drive Madison, WI 53705, 1 ANDREW FELT, 3641 Jordan Lane, Stevens Point, WI 54481, CANDICE OWLEY, 2785 South Delaware Avenue, Milwaukee, WI 53207, CONNIE SMITH, 4049 South 5th Place, Milwaukee, WI 53207, JANET BEWLEY, 60995 Pike River Road, Mason, WI 54856, Plaintiffs, v. ROBIN VOS, in his official capacity as Wisconsin Assembly Speaker, 321 State St, Madison, WI 53702, ROGER ROTH, in his official capacity as Wisconsin Senate President, State Capitol—Room 220 South Madison, WI 53707 JIM STEINEKE, in his official capacity as Wisconsin Assembly Majority Leader, 2 E Main St, Madison, WI 53703 SCOTT FITZGERALD, in his official capacity as Wisconsin Senate Majority Leader, 206 State St, Madison, WI 53702 JOSH KAUL, in his official capacity as Attorney General of the State of Wisconsin 7 W Main St, Madison, WI 53703, 2 TONY EVERS, in his official capacity as Governor of the State of Wisconsin, State Capitol—Room 115 East Madison, WI 53702, Defendants. -

THE WISCONSIN SURVEY - Spring 2002

THE WISCONSIN SURVEY - Spring 2002 http://www.snc.edu/survey/report_twss02.html THE WISCONSIN SURVEY Survey Information: Survey Sponsors: Wisconsin Public Radio and St. Norbert College Survey Methodology: Random statewide telephone survey of Wisconsin residents. The random digit dial method selects for both listed and unlisted phone numbers. Eight attempts were made on each telephone number randomly selected to reach an adult in the household. Survey History: the survey has been conducted biannually since 1984. Data Collection Time Period: 3/20/02 - 4/7/02 N = 407 Error Rate: 4.864% at the 95% confidence level. The margin of error will be larger for subgroups. Key Findings: According to the Wisconsin Public Radio - St. Norbert College Survey Center poll, if the general election were held today, Governer McCallum would be ahead of Democratic or third party contenders in hypothetical election pairings of candidates. However, in the race between McCallum and Doyle, the percentage lead McCallum has over Doyle is within the margin of error of the survey. In other words, there is no statistically significant difference between the two candidates. In the hypothetical pairings of McCallum against the other Democratic Party candidates, McCallum appears to be well ahead. Another indicator of sentiment for the candidates is the "favorable" and "unfavorable" ratings. Here, Doyle rates the highest, with 36% of respondents saying they had a favorable impression of him, compared to McCallum's 31%. Similarly, only 18% of respondents said they had an unfavorable opinion of Doyle compared to 35% of respondents saying they had an unfavorable opinion of McCallum. So, why is there no significant difference in the polls between McCallum and Doyle when Doyle seems to be more highly esteemed? More people have not heard of Doyle than McCallum and those who have not heard of Doyle are likely to vote for McCallum. -

Harassment Case Hearing Delayed Regent Challenged by Students On

THE immMmmmmUW M*;-* ,^ OST Tuesday, October 14, 1986 The University of Wisconsin—Milwaukee Volume 31, Number 11 Harassment case hearing delayed Former swim coach says UWM, regents, named in $1 million sex harassment suit tional injuries. the Occupational Therapy Prog he will sue University by Michael Szymanski Frederick Pairent, dean of the ram, and James McPherson, a School of Allied Health Profes professor in the School of Allied 'Housecleaning' blamed for loss of job ormer UWM Assistant Pro sions, and former assistant dean, Health Professions, are listed in fessor Katherine King has Stephen Sonstein, are also the complaint as defendants. by Michael Mathias Ffiled a lawsuit in federal named in the complaint. The The case, which was initially court demanding a jury trial a- complaint accuses Sonstein of scheduled to open Monday, has ormer UWM swim coach Fred Russell said Monday he gainst the UW System's Board of sexually harassing King during been postponed and is being plans to file a lawsuit against the University to contest what Regents for alleged sex discrimi the 1980-81 academic year. rescheduled at the request of he calls a violation of his contract that eventually led to his nation, sexual harassment and King left the University in 1983 Federal Judge John Reynolds. F resignation last July. damage to her professional repu due to an illness. King said the trial will convene Russell, who was named last year's coach of the year by the tation and career, according to According to the complaint, soon. NAIA and had been UWM's swim coach for the past 10 years, the court complaint. -

Wisconsin in La Crosse

CONTENTS Wisconsin History Timeline. 3 Preface and Acknowledgments. 4 SPIRIT OF David J. Marcou Birth of the Republican Party . 5 Former Governor Lee S. Dreyfus Rebirth of the Democratic Party . 6 Former Governor Patrick J. Lucey WISCONSIN On Wisconsin! . 7 A Historical Photo-Essay Governor James Doyle Wisconsin in the World . 8 of the Badger State 1 David J. Marcou Edited by David J. Marcou We Are Wisconsin . 18 for the American Writers and Photographers Alliance, 2 Professor John Sharpless with Prologue by Former Governor Lee S. Dreyfus, Introduction by Former Governor Patrick J. Lucey, Wisconsin’s Natural Heritage . 26 Foreword by Governor James Doyle, 3 Jim Solberg and Technical Advice by Steve Kiedrowski Portraits and Wisconsin . 36 4 Dale Barclay Athletes, Artists, and Workers. 44 5 Steve Kiedrowski & David J. Marcou Faith in Wisconsin . 54 6 Fr. Bernard McGarty Wisconsinites Who Serve. 62 7 Daniel J. Marcou Communities and Families . 72 8 tamara Horstman-Riphahn & Ronald Roshon, Ph.D. Wisconsin in La Crosse . 80 9 Anita T. Doering Wisconsin in America . 90 10 Roberta Stevens America’s Dairyland. 98 11 Patrick Slattery Health, Education & Philanthropy. 108 12 Kelly Weber Firsts and Bests. 116 13 Nelda Liebig Fests, Fairs, and Fun . 126 14 Terry Rochester Seasons and Metaphors of Life. 134 15 Karen K. List Building Bridges of Destiny . 144 Yvonne Klinkenberg SW book final 1 5/22/05, 4:51 PM Spirit of Wisconsin: A Historical Photo-Essay of the Badger State Copyright © 2005—for entire book: David J. Marcou and Matthew A. Marcou; for individual creations included in/on this book: individual creators. -

1969 NGA Annual Meeting

Proceedings OF THE NATIONAL GOVERNORS' CONFERENCE 1969 SIXTY-FIRST ANNUAL MEETING BROADMOOR HOTEL • COLORADO SPRINGS, COLORADO AUGUST 31-SEPTEMBER 3, 1969 THE NATIONAL GOVERNORS' CONFERENCE IRON WORKS PIKE LEXINGTON, KENTUCKY 40505 THE COUNCil OF S1'ATE GOVERNMENTS IRON WORKS PIKE LEXINGTON, KENTUCKY 40511 J Published by THE NATIONAL GOVERNORS' CONFERENCE IRON WORKS PIKE LEXINGTON, KENTUCKY 40505 CONTENTS Executive Committee Rosters v Other Committees of the Conference vi Governors and Guests in Attendance viii Program of the Annual Meeting xi Monday Sessions-September 1 Welcoming Remarks-Governor John A. Love 1 Address of the Chairman-Governor Buford Ellington 2 Adoption of Rules of Procedure . 4 Remarks of Monsieur Pierre Dumont 5 "Governors and the Problems of the Cities" (including reports and policy statements of the Committee on Community Development and Urban Relations), Governor Richard J. Hughes presiding .. 6 Remarks of Secretary George Romney . .. 15 "Revenue Sharing" (including reports and policy statements of the Committee on Executive Management and Fiscal Affairs), Governor Daniel J. Evans presiding . 33 Remarks of Dr. Arthur F. Burns .. 36 Remarks of Vice-President Spiro T. Agnew 43 State Ball Remarks of Governor John A. Love 57 Remarks of Governor Buford Ellington 57 Address by the President of the United States 58 Tuesday Sessions-September 2 "Major Issues in Human Resources" (including reports and policy statements of the Committee on Human Resources), Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller presiding . 68 Remarks of Secretary George P. Shultz 87 "Transportation" (including reports and policy statements of the Committee on Transportation, Commerce, and Technology), Governor John A. Love presiding 95 Remarks of Secretary John A. -

Eyes on Janesville When Speaker Ryan Was Ready to Endorse, His Hometown Newspaper Broke the Story

FEATURE: Meet the Woodville Leader, Sun-Argus. Page 2 THETHE June 9, 2016 BulletinBulletinNews and information for the Wisconsin newspaper industry All eyes on Janesville When Speaker Ryan was ready to endorse, his hometown newspaper broke the story BY JAMES DEBILZEN vative agenda. Communications Director Schwartz said the news t wasn’t a scoop in the tra- was unex- ditional telling of newsroom pected. On Ilore. There were no anony- Wednesday, mous sources, cryptic messages June 1, opin- or meetings with shadowy fig- ion editor ures in empty parking garages. Greg Peck Regardless, editor Sid was contacted Schwartz of The Gazette in Sid Schwartz by Ryan’s of- Angela Major photo | Janesville said it was “fun to fice to discuss Courtesy of The Gazette have a national news item that the publi- we got to break,” referencing cation of a ABOVE: House Speaker Paul being the first media outlet to column about Ryan discusses his endorse- announce the Speaker of the “Republican ment of Donald Trump and his House was endorsing the pre- unity and the policy vision with members of sumptive Republican candidate House policy The Gazette’s editorial Board for the presidency. agenda.” on Friday, June 3. Speaker Paul Ryan, R-Janes- “We didn’t LEFT: The endorsement ville, announced in a column really know story broke on The Gazette’s first published on The Gazette’s what we website, www.gazettextra. website on June 2 that he would Greg Peck were getting,” com, on Thursday afternoon. vote for businessman Donald Schwartz Friday’s front page carried the Trump in November, lending said. -

Fondy Republicans to Honor Former Governor

Fondy Republicans to Honor Former Governor McCallum to be honored with First “McCallum Award” For Immediate Release August 8, 2017 Contact: Rohn W. Bishop [email protected] 920.210.1063 www.fdlgop.com @RohnW.Bishop Waupun - The Republican Party of Fond du Lac County will be honoring Former Wisconsin Governor, and Fond du Lac native, Scott McCallum at their annual “Scotch and Cigar” event on October 5. “We’re creating a lifetime achievement award, to be given out annually to a local Fond du Lac Republican who’s worked tirelessly for the Republican Party of Fond du Lac County, and/or has gone on to bigger and better things,” said Rohn Bishop, Chairman of the Republican Party of Fond du Lac County. “We’re going to call it the “McCallum Award” and the first recipient will be our former Governor, Scott McCallum.” "I am deeply honored to have an award for life-time achievement named after me,” said Governor Scott McCallum. “It is especially meaningful coming from my hometown which includes my family and many long time friends. It is humbling in that there are so many other wonderful, hard-working people in Fond du Lac who are deserving of such recognition." The first ever “Scott McCallum Lifetime Achievement Award” will be presented to Governor McCallum at the Fond du Lac Yacht Club on Thursday October 5 at the annual Republican Party of Fond du Lac County’s ‘Scotch and Cigar’ event. The event begins at 7pm and is $50 per person or $75 per couple. “This is our most unique event we do every year, and we’re so thrilled to have the opportunity to honor Governor McCallum with an award to be handed out annually in his name.” Bishop said. -

EXECUTIVE ORDERS 2001−2002 Issued by Scott Mccallum Note: Pursuant to S

File inserted into Admin. Code 10−1−2003. May not be current beginning 1 month after insert date. For current adm. code see: http://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/code/admin_code 1 EXECUTIVE OFFICE EXECUTIVE ORDERS 2001−2002 Issued by Scott McCallum Note: Pursuant to s. 35.93 (3), Stats., the revisor of statutes shall publish with the EXECUTIVE ORDER 21. Directing the Public Service Wisconsin Administrative Register those executive orders which are to be in effect Commission to Redirect Funds Intended to Provide Voice Mail for more than 90 days or an informative summary thereof. Notice of recently issued Executive Orders are published in the end−of−month Register. Services for the Homeless. EXECUTIVE ORDER 418. Relating to a Proclamation that EXECUTIVE ORDER 22. Relating to a Special Election for the Flag of the United States and the Flag of the State of Wisconsin the Forty−second Assembly District. be Flown at Half−Staff as a Mark of Respect for Assistant Fire EXECUTIVE ORDER 23. Relating to a Proclamation that Chief Dana Johnson of the Grantsburg Volunteer Fire the Flag of the United States and the Flag of the State of Wisconsin Department. be Flown at Half−Staff Due to Terrorist Attacks on the United EXECUTIVE ORDER 1. Relating to the Findings of the States. Governor’s Task Force on Racial Profiling. EXECUTIVE ORDER 24. Relating to the Governor’s History: Signed March 6, 2001. Pardon Advisory Board. EXECUTIVE ORDER 2. Relating to a Proclamation that the WHEREAS, Article V, Section 6 of the Wisconsin Flag of the United States and the Flag of the State of Wisconsin Constitution vests in the Governor the exclusive and discretionary be Flown at Half−Staff as a Mark of Respect for Specialist Jason power to grant pardons, commutations and reprieves; and D. -

Historic Forest Hill Cemetery

She is buried among “her boys”. “her among buried is She monument. expense she maintained the plot until her death in 1897. 1897. in death her until plot the maintained she expense attractive their in reflected is which classics, the of love world-wide recognition. world-wide Madison to manage the Vilas House Hotel. At her own own her At Hotel. House Vilas the manage to Madison and appreciation an shared They books. several of author University of Wisconsin, many of whom have achieved achieved have whom of many Wisconsin, of University Louisiana-born widow named Alice Waterman came to to came Waterman Alice named widow Louisiana-born and scholar, leader, civic a was (1870-1963) Slaughter place of numerous faculty and administrators from the the from administrators and faculty numerous of place By1868 these graves were being neglected when a a when neglected being were graves these By1868 Taylor Elizabeth Gertrude wife His subjects. Latin state, and the nation. In addition, it is the final resting resting final the is it addition, In nation. the and state, in Confederate Rest. Confederate in and classical on monographs and essays of author and have played significant roles in the history of the city, the the city, the of history the in roles significant played have and died due to exposure and disease. They were buried buried were They disease. and exposure to due died and Wisconsin, of University the at Latin of professor a was Forest Hill contains the graves of many persons who who persons many of graves the contains Hill Forest River were sent to prison at Camp Randall. -

“MRAC” Version 2019 1917-2019 – 102 YEARS!

The History Of The Milwaukee Radio Amateurs’ Club Inc. “MRAC” Version 2019 1917-2019 – 102 YEARS! 100 Years of ARRL Affiliation! The History of the Milwaukee Radio Amateurs’ Club Inc. 2019 Edition Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................... 3 Credits/Revision History ................................................................................. 6 The History of the History ............................................................................... 8 The MRAC Archives ....................................................................................... 11 The Amateur’s Code ...................................................................................... 13 A Historical Timeline ..................................................................................... 14 The Beginning as Told By Someone Who Was There ...............................122 ARRL Club Affiliation ...................................................................................125 A Brief History of MRAC Bylaws .................................................................129 From Dollars to Doughnuts .........................................................................132 The MacArthur Parade .................................................................................134 Emil Felber W9RH ........................................................................................135 Set Another Place for Sister Margaret ........................................................137 -

Family Gives to Help Future Hockey Badgers Tongue Unlocks Part of the Amazing Brain Raising The

A report from WISCONSIN The University of Wisconsin Foundation Summer 2010 insights Family gives to help future hockey Badgers Tongue unlocks part of the amazing brain Raising the bar: L&S Honors turns 50 Chancellor’s Message Remarkable Camp Randall in February filled with cheering fans for Badger hockey—remarkable. Inventive minds and their inventions at the College of Engineering’s Innovation Days—remarkable. Students organizing events to help the people of Haiti—remarkable. The daily activity and energy everywhere at the Biddy Martin University of Wisconsin-Madison—doubly remarkable. I could go on, but you get my point. This is a remarkable place. The campus is beautiful in any season, but especially now, as I write this message. Our world-class faculty motivates and urges students to aim boldly and think deeply. We are guided by experienced and devoted staff and administrators. In research, we are consistently among the top three nationally. I especially want to single out our students. While projected higher tuition costs at many colleges and universities bring angry demonstrations, our students actually voted in favor of a tuition increase in 2009 via the Madison Initiative for Undergraduates. The Madison Initiative is already providing need-based financial aid, additional faculty for in-demand courses and enhanced student services. A year ago, students traveled to a Board of Regents meeting to voice their support for this plan. Now, students are participating in making decisions with regard to allocation of Madison Initiative funds earmarked for student services. I am proud of these remarkable Badgers. Mixed with this pride is a sense of responsibility to the talented, ambitious, hard-working young people who have earned the opportunity to attend the UW-Madison, who have been accepted but who do not have the financial means to attend. -

2019-2020 Wisconsin Blue Book: Historical Lists

HISTORICAL LISTS Wisconsin governors since 1848 Party Service Residence1 Nelson Dewey . Democrat 6/7/1848–1/5/1852 Lancaster Leonard James Farwell . Whig . 1/5/1852–1/2/1854 Madison William Augustus Barstow . .Democrat 1/2/1854–3/21/1856 Waukesha Arthur McArthur 2 . Democrat . 3/21/1856–3/25/1856 Milwaukee Coles Bashford . Republican . 3/25/1856–1/4/1858 Oshkosh Alexander William Randall . .Republican 1/4/1858–1/6/1862 Waukesha Louis Powell Harvey 3 . .Republican . 1/6/1862–4/19/1862 Shopiere Edward Salomon . .Republican . 4/19/1862–1/4/1864 Milwaukee James Taylor Lewis . Republican 1/4/1864–1/1/1866 Columbus Lucius Fairchild . Republican. 1/1/1866–1/1/1872 Madison Cadwallader Colden Washburn . Republican 1/1/1872–1/5/1874 La Crosse William Robert Taylor . .Democrat . 1/5/1874–1/3/1876 Cottage Grove Harrison Ludington . Republican. 1/3/1876–1/7/1878 Milwaukee William E . Smith . Republican 1/7/1878–1/2/1882 Milwaukee Jeremiah McLain Rusk . Republican 1/2/1882–1/7/1889 Viroqua William Dempster Hoard . .Republican . 1/7/1889–1/5/1891 Fort Atkinson George Wilbur Peck . Democrat. 1/5/1891–1/7/1895 Milwaukee William Henry Upham . Republican 1/7/1895–1/4/1897 Marshfield Edward Scofield . Republican 1/4/1897–1/7/1901 Oconto Robert Marion La Follette, Sr . 4 . Republican 1/7/1901–1/1/1906 Madison James O . Davidson . Republican 1/1/1906–1/2/1911 Soldiers Grove Francis Edward McGovern . .Republican 1/2/1911–1/4/1915 Milwaukee Emanuel Lorenz Philipp . Republican 1/4/1915–1/3/1921 Milwaukee John James Blaine .