Collingridge, S. R. July 2019 Doctor of Professional Studies in Practical Theology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HISTORY of FETCHAM CHURCH Draft 23.3.97 J Mettam

pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com HISTORY OF FETCHAM CHURCH Draft 23.3.97 J Mettam INTRODUCTION The oldest parts of Fetcham Church were built about 1,000 years ago. At that time The Street extended southward between the church and the manor house (where Fetcham Park House now stands) to join the path over the Downs to West Humble. The Street also continued north, bearing right past where Barracks Farm now is, to ford the Mole on the way to Kingston. The Street was crossed by the Harroway, an ancient route which came into existence in BC600-300 from North Kent to the tin mining areas of Cornwall. The Harroway followed the spring line of the Lower Road in the summer and a drier route near the Leatherhead Guildford road in the winter. The Harroway became an important link between the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of Kent and Wessex. Fetcham must have been one of the earliest areas of Anglo-Saxon settlement with 6th Century burial grounds on Hawks Hill and at Watersmeet. The village was clustered in the nearest part of The Street just north of the church and manor house, which is thought to have developed around the site of a Roman villa or farmhouse. The present parish boundaries probably represent the ghost of the Roman estate. The varied soil types were well suited to the mixed communal farming methods of the Anglo Saxons. The main open fields were on calcareous loam on the slopes SE and SW from the Church, which could still be described in 1809 as some of the best soil in Surrey. -

Clergy Handbook: Office Holders Terms and Condi�Ons of Service

[Inten�onally Blank] Diocese of Exeter Clergy Handbook: Office Holders Terms and Condi�ons of Service Contents Page Welcome from the Bishop of Exeter 3 Introduc�on 4 Sec�on 1: Diocese of Exeter – Who We Are 6 Sec�on 2: Appointment and Office 13 2.1 Varieties of Tenure 13 2.2 Key Documents 15 2.3 Nominated Officers 16 2.4 Fixed Term Appointments 17 2.5 Priests Over 70 18 2.6 Other Requirements 19 2.7 Housing 22 Sec�on 3: Managing Finances in Office 25 3.1 Grants 25 3.2 Expenses 26 3.3 Stipend and Pensions 26 3.4 Payroll and Tax 28 3.5 Financial Help 29 Sec�on 4: Day to Day Working Arrangements 31 4.1 Personal Details 31 4.2 Rest Periods and Annual Leave 31 4.3 Sickness 32 4.4 Other Types of Leave 35 Sec�on 5: Health, Safety and Security 37 5.1 Health and Safety 5.2 Personal Security 5.3 Safeguarding Sec�on 6: IT and Communica�ons 38 6.1 IT Security and Data Protection 38 6.2 Giving Professional and Personal References 40 6.3 Working With the Media 41 6.4 Social Media Guidelines 42 September 2020 1 Sec�on 7: Ongoing Ministry 44 7.1 Growing in Ministry 44 7.2 Ministerial Development Reviews 44 7.3 Continuing Ministerial Development 45 Sec�on 8: Welfare and Wellbeing 46 8.1 Clergy Wellbeing Covenant 46 8.2 Support During Sickness Absence 46 8.3 Pastoral Care and Counselling 47 8.4 Relationship Support 48 8.5 Retirement support 50 Sec�on 9: Work Life Balance (Family Friendly Policies) 52 9.1 Legal Entitlement to Statutory Leave and Pay 52 9.2 Maternity Leave and Pay 54 9.3 Adoption Leave and Pay 56 9.4 Paternity Leave and Pay 58 9.5 Shared Parental -

Profile for New Vicar

PROFILE FOR NEW VICAR Growing through making Whole-life Disciples CONTENTS The Parish 4 The Church 6 Sunday Services 8 Children’s Work 9 All Age Services 10 Midweek Activities 11 Youthwork 12 Uniformed Organisations 13 Music 14 Occasional Offices 15 Festivals 16 Church Groups 17 Life Groups 18 Mission & Social Action 19 The Staff Team 23 A Training Parish 24 PCC & Working Groups 25 Finances 26 The Deanery 27 The Buildings 28 Conditions of Service 30 Our New Vicar…? 31 3 St Luke’s Church is located on the Cassiobury Estate in Watford, Hertfordshire. The town has a population of approximately 90,000. It is situated 18 miles north of London with mainline and underground links into the centre of London in less than 30 minutes; Watford Junction station is on the mainline between London Euston and Birmingham. It is just inside the M25, near Junction 19 and near the M1, Junctions 5 and 6. It is also close to Heathrow and Luton Airports. 4 There are many facilities within walking distance of the church: • Local large convenience store including Post Office • Cafe, take-away, pharmacy, dry cleaners, dentist and hairdresser restaurants and pub • Sun Sports Ground has both a party pavilion and games pitches • A tennis club with outdoor courts and floodlights • An outdoor and indoor bowling club • Christian Science Church • Excellent infant and junior schools on and off the estate • Excellent state secondary schools nearby • Cassiobury Park – 200 acres of beautiful parkland within walking distance – has a children’s paddling pool, play area and miniature train. A new Café Hub was built in 2017 • Whippendell Woods adjoining Cassiobury Park • West Herts Golf Club, one of several in the area • Grand Union Canal – with boating and fishing facilities The expensive private housing is mainly owner occupied. -

A Report on the Developments in Women's Ministry in 2018

A Report on the Developments in Women’s Ministry in 2018 WATCH Women and the Church A Report on the Developments in Women’s Ministry 2018 In 2019 it will be: • 50 years since women were first licensed as Lay Readers • 25 years since women in the Church of England were first ordained priests • 5 years since legislation was passed to enable women to be appointed bishops In 2018 • The Rt Rev Sarah Mullaly was translated from the See of Crediton to become Bishop of London (May 12) and the Very Rev Viv Faull was consecrated on July 3rd, and installed as Bishop of Bristol on Oct 20th. Now 4 diocesan bishops (out of a total of 44) are women. In December 2018 it was announced that Rt Rev Libby Lane has been appointed the (diocesan) Bishop of Derby. • Women were appointed to four more suffragan sees during 2018, so at the end of 2018 12 suffragan sees were filled by women (from a total of 69 sees). • The appointment of two more women to suffragan sees in 2019 has been announced. Ordained ministry is not the only way that anyone, male or female, serves the church. Most of those who offer ministries of many kinds are not counted in any way. However, WATCH considers that it is valuable to get an overview of those who have particular responsibilities in diocese and the national church, and this year we would like to draw attention to The Church Commissioners. This group is rarely noticed publicly, but the skills and decisions of its members are vital to the funding of nearly all that the Church of England is able to do. -

GS Misc 1158 GENERAL SYNOD 1 Next Steps on Human Sexuality Following the February 2017 Group of Sessions, the Archbishops Of

GS Misc 1158 GENERAL SYNOD Next Steps on Human Sexuality Following the February 2017 Group of Sessions, the Archbishops of Canterbury and York issued a letter on 16th February outlining their proposals for continuing to address, as a church, questions concerning human sexuality. The Archbishops committed themselves and the House of Bishops to two new strands of work: the creation of a Pastoral Advisory Group and the development of a substantial Teaching Document on the subject. This paper outlines progress toward the realisation of these two goals. Introduction 1. Members of the General Synod will come back to the subject of human sexuality with very clear memories of the debate and vote on the paper from the House of Bishops (GS 2055) at the February 2017 group of sessions. 2. Responses to GS 2055 before and during the Synod debate in February underlined the point that the ‘subject’ of human sexuality can never simply be an ‘object’ of consideration for us, because it is about us, all of us, as persons whose being is in relationship. Yes, there are critical theological issues here that need to be addressed with intellectual rigour and a passion for God’s truth, with a recognition that in addressing them we will touch on deeply held beliefs that it can be painful to call into question. It must also be kept constantly in mind, however, that whatever we say here relates directly to fellow human beings, to their experiences and their sense of identity, to their lives and to the loves that shape and sustain them. -

August Prayer Diary 2010

Tuesday 24th Weaverthorpe, St Peter Helperthorpe, St Andrew Kirby Grindaylthe, St Andrew Bartholomew the Weaverthorpe, St Mary West Lutton, St Mary Wharram le Street Diocese of York Prayer Diary --- August 2010 Apostle Clergy: Vacant Please pray for the Churchwardens as they continue to manage the running of the Parish York Minster during the ongoing vacancy. Sunday 1st Diocese of George (South Africa), Bishop Donald Harker 9th Sunday after Dean, The Very Reverend Keith Jones, Chancellor, The Revd Canon Glyn Webster, Trinity Precentor, Vacant, Canon Theologian, The Revd Canon Dr Jonathan Draper. Wednesday 25th West Buckrose (8) In your prayers for the Minster please would you include the craftsmen in stone, glass and Rector, The Revd Jenny Hill, other materials who are constantly renewing the ancient structure and show it as a place We ask for prayers as we commit ourselves to the mission initiative of Back to Church alive and responding to the Holy Spirit, the Lord and Giver of Life. Sunday. We give thanks for the growing congregation which attends our new All-Age Pray for The Scottish Episcopal Church. Archbishop David Chillingworth. Service, and for the steady growth from small beginnings of our ‘Young Bucks’ post- Hull Deanery—Central and North Hull confirmation group. We are grateful too for retired clergy Revd Norman Lewis, and reader Monday 2nd Eric Thompson who help regularly within our Parish, and pray for the work of our Rural Dean of Hull and Area Dean, The Revd Canon David Walker, Lay Chair, Mr J V Ayre, Pastoral Team. Secretary of Deanery Synod, Mrs C Laycock, Reader, Canon S Vernon, Deanery Finance Diocese of Georgia (Province IV, USA), Bishop Henry Louttit Adviser, I R Nightingale Please pray that the Deanery, as it reviews the deployment of its human resources and the Thursday 26th Castle Howard Chaplaincy use of its buildings, may find in it an opportunity for renewal. -

Download 1 File

GHT tie 17, United States Code) r reproductions of copyrighted Ttain conditions. In addition, the works by means of various ents, and proclamations. iw, libraries and archives are reproduction. One of these 3r reproduction is not to be "used :holarship, or research." If a user opy or reproduction for purposes able for copyright infringement. to accept a copying order if, in its involve violation of copyright law. CTbc Minivers U^ of Cbicatjo Hibrcmes LIGHTFOOT OF DURHAM LONDON Cambridge University Press FETTER LANE NEW YORK TORONTO BOMBAY CALCUTTA MADRAS Macmillan TOKYO Maruzen Company Ltd All rights reserved Phot. Russell BISHOP LIGHTFOOT IN 1879 LIGHTFOOT OF DURHAM Memories and Appreciations Collected and Edited by GEORGE R. D.D. EDEN,M Fellow Pembroke Honorary of College, Cambridge formerly Bishop of Wakefield and F. C. MACDONALD, M.A., O.B.E. Honorary Canon of Durham Cathedral Rector of Ptirleigb CAMBRIDGE AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS 1933 First edition, September 1932 Reprinted December 1932 February PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN 1037999 IN PIAM MEMORIAM PATRIS IN DEO HONORATISSIMI AMANTISSIMI DESIDERATISSIMI SCHEDULAS HAS QUALESCUNQUE ANNOS POST QUADRAGINTA FILII QUOS VOCITABAT DOMUS SUAE IMPAR TRIBUTUM DD BISHOP LIGHTFOOT S BOOKPLATE This shews the Bishop's own coat of arms impaled^ with those of the See, and the Mitre set in a Coronet, indicating the Palatinate dignity of Durham. Though the Bookplate is not the Episcopal seal its shape recalls the following extract from Fuller's Church 5 : ense History (iv. 103) 'Dunelmia sola, judicat et stola. "The Bishop whereof was a Palatine, or Secular Prince, and his seal in form resembleth Royalty in the roundness thereof and is not oval, the badge of plain Episcopacy." CONTENTS . -

AD CLERUM: 11 July 2018

AD CLERUM: 11 July 2018 Dear Colleagues There can be few better days in the Church’s calendar than the Feast of St Benedict to announce the appointment of the Venerable Jackie Searle as the next Bishop of Crediton. The announcement was made from Downing Street this morning. Prior to her ordination, Jackie trained as a Primary School teacher, specialising in English. Following her ordination and two curacies in London, Jackie became a Lecturer in Applied Theology at Trinity College, Bristol. From there she moved to the Diocese of Derby becoming Vicar of Littleover, Rural Dean and Dean of Women’s Ministry. In 2012 she moved to her current appointment as Archdeacon of Gloucester and Canon Residentiary of Gloucester Cathedral. She is married to David Runcorn and they have two grown up children, Joshua and Simeon. Jackie is a person of wide sympathies with a deep love of Christ. She has been a Training Partner with Bridge Builders for several years, specialising in conflict transformation, and will bring to her new role the same mixture of compassion, integrity and professionalism that has characterised all her work. She understands the challenges and opportunities of rural ministry well and will enrich the life of the church in Devon in all sorts of ways. I look forward to welcoming her to the Diocese this autumn. She will be consecrated in London on the Feast of St Vincent de Paul, Thursday 27th September, and her welcome service will be in Exeter Cathedral at 4pm on Sunday 14th October. More details about both services will follow in due course. -

Porvoo Prayer Diary 2021

PORVOO PRAYER DIARY 2021 The Porvoo Declaration commits the churches which have signed it ‘to share a common life’ and ‘to pray for and with one another’. An important way of doing this is to pray through the year for the Porvoo churches and their Dioceses. The Prayer Diary is a list of Porvoo Communion Dioceses or churches covering each Sunday of the year, mindful of the many calls upon compilers of intercessions, and the environmental and production costs of printing a more elaborate list. Those using the calendar are invited to choose one day each week on which they will pray for the Porvoo churches. It is hoped that individuals and parishes, cathedrals and religious orders will make use of the Calendar in their own cycle of prayer week by week. In addition to the churches which have approved the Porvoo Declaration, we continue to pray for churches with observer status. Observers attend all the meetings held under the Agreement. The Calendar may be freely copied or emailed for wider circulation. The Prayer Diary is updated once a year. For corrections and updates, please contact Ecumenical Officer, Maria Bergstrand, Ms., Stockholm Diocese, Church of Sweden, E-mail: [email protected] JANUARY 3/1 Church of England: Diocese of London, Bishop Sarah Mullally, Bishop Graham Tomlin, Bishop Pete Broadbent, Bishop Rob Wickham, Bishop Jonathan Baker, Bishop Ric Thorpe, Bishop Joanne Grenfell. Church of Norway: Diocese of Nidaros/ New see and Trondheim, Presiding Bishop Olav Fykse Tveit, Bishop Herborg Oline Finnset 10/1 Evangelical Lutheran Church in Finland: Diocese of Oulu, Bishop Jukka Keskitalo Church of Norway: Diocese of Sør-Hålogaland (Bodø), Bishop Ann-Helen Fjeldstad Jusnes Church of England: Diocese of Coventry, Bishop Christopher Cocksworth, Bishop John Stroyan. -

Urban Estates Evangelism Conference – 9-10Th October 2017

Urban Estates Evangelism Conference – 9-10th October 2017 Theological Reflection – led by Rev Dr Jill Duff – Estates and the Gospel FULL VERSION My heart leapt when Bishop Philip invited me to give this theological reflection Pretty much all 15 years of my ordained ministry has been spent in urban deprivation areas of Liverpool Diocese. What I am to say is formed by countless friends who live in urban areas in the North West. One friend in particular has personally contributed – you’ll meet her shortly. For my day job, I’m Director of St Mellitus College North West, based at Liverpool Cathedral – where I teach New Testament, mission and church planting. We are the first Full Time ordination college in the North West for over 40 years and we are trying to build on the heritage (or re-open the wells) of St Aidan’s College in Birkenhead. This College closed in 1969. When they opened in 1846 they were ahead of their time – these were the days when you either trained for ordination at Oxford, Cambridge or St Aidan’s. They had the vision of training the ordinary man for ordination in the C of E – dockers, labourers, postmen. You still see this in the St Aidan’s old boys today. It was also an earlier version of context-based training. The Vicar who founded it, Joseph Bayliss, saw the growing need for the gospel across the water in the burgeoning city of Liverpool, so ordinands would spend their afternoons at the coal- face of ministry with the poor in the slums. -

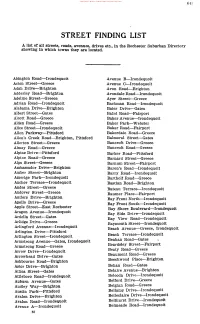

Street Finding List

Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Miscellaneous Directories STREET FINDING LIST A list of all streets, roads, avenues, drives etc., in the Rochester Suburban Directory showing in which towns they are located. Abington Road Irondequoit Avenue B Irondequoit Acton Street Greece Avenue C Irondequoit Adah Drive Brighton Avon Road Brighton Adderley Road Brighton Avondale Road Irondequoit Adeline Street Greece Ayer Street Greece Adrian Road Irondequoit Bachman Road Irondequoit Alabama Drive Brighton Baier DriveGates Albert Street Gates Baird Road Fairport Alcott Road Greece Baker Avenue Irondequoit Alden Road Greece Baker Park Webster Alice Street Irondequoit Baker Road Fairport Allen Parkway Pittsford Bakerdale Road Greece Allen's Creek RoadBrighton, Pittsford Balmoral Street Gates Allerton Street Greece Bancroft Drive Greece Almay Road Greece Bancroft Road Greece Alpine Drive Pittsford Barker RoadPittsford Alpine Road Greece Barnard Street Greece Alps Street Greece Barnum Street Fairport Ambassador Drive Brighton Baron's Road Irondequoit Amber Street Brighton Barry RoadIrondequoit Amerige Park Irondequoit Bartholf Road Greece Anchor Terrace Irondequoit Bastian Road Brighton Andes Greece Street Bateau Terrace Irondequoit Andover Greece Street Baumer Place Fairport Antlers Drive Brighton Bay Front North Irondequoit Apollo Drive Greece Bay Front South Irondequoit Street East Rochester Apple Bay Shore Boulevard Irondequoit Avenue Aragon Irondequoit Bay Side Drive Irondequoit Ardella Street Gates Bay View Road Irondequoit Drive Greece -

Church of England's Ecumenical Relations 2020 Annual Report

CHURCH OF ENGLAND’S ECUMENICAL RELATIONS 2020 ANNUAL REPORT 1 Contents Introduction to the annual report on ecumenical relations 2020 ................................................................ 3 Relationships with other churches ................................................................................................................ 5 BAPTISTS ..................................................................................................................................................... 5 CHURCH OF SCOTLAND ............................................................................................................................... 6 EVANGELISCHE KIRCHE IN DEUTSCHLAND (EKD) ........................................................................................ 8 FRENCH PROTESTANT CHURCHES ............................................................................................................10 LOCAL UNITY .............................................................................................................................................12 METHODIST CHURCH ................................................................................................................................15 OLD CATHOLICS OF THE UNION OF UTRECHT ..........................................................................................19 ORTHODOX CHURCHES .............................................................................................................................20 PENTECOSTAL CHURCHES .........................................................................................................................23