Articles Great Salt Lake Paper 2016 (01048374)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Provo River Watershed Plan Introduction Public Water Systems

Provo River Watershed Plan Introduction Public water systems (PWSs) in the State of Utah who treat surface water or groundwater under the direct influence of surface water are required by the Drinking Water Source Protection (DWSP) Rule, to develop, submit and implement a DWSP Plan for all sources of public drinking water. All PWSs are required to delineate watershed protection zones, develop a listing of potential contamination sources within the protection zones, and subsequently prepare and implement management plans to provide protection for surface water sources within the watershed protection zones. The following PWSs along the Wasatch Front have formed the Watershed Protection Coalition (Coalition) and have initiated a cooperative project to develop their DWSP Plans for the Provo River Basin Watershed: Central Utah Water Conservancy District Jordan Valley Water Conservancy District Metropolitan Water District of Salt Lake & Sandy The mission of the Watershed Protection Coalition is to: Work cooperatively to understand the watershed, identify priorities, and develop and implement long-term strategies to protect the drinking water source(s) from contamination, as a primary safeguard to protect the public health. Support federal, state and local agencies that are empowered with the authority and jurisdiction necessary to protect the watershed(s) and drinking water source(s) through regulations, rules and ordinances. The members of the Coalition, all of whom are active signing and funding members of the Provo River Watershed Council (PRWC), are working together to protect regional surface water resources. By working together in cooperation with other agencies and programs, the Coalition is able to maximize efficiency, and jointly manage potential contamination sources. -

GOVERNANCE & OVERSIGHT NARRATIVE Local Authority

GOVERNANCE & OVERSIGHT NARRATIVE Local Authority: Wasatch County Instructions: In the cells below, please provide an answer/description for each question. PLEASE CHANGE THE COLOR OF SUBSTANTIVE NEW LANGUAGE INCLUDED IN YOUR PLAN THIS YEAR! 1) Access & Eligibility for Mental Health and/or Substance Abuse Clients Who is eligible to receive mental health services within your catchment area? What services (are there different services available depending on funding)? Wasatch County Family Clinic-Wasatch Behavioral Health Special Service District (WCFC-WMH) is a comprehensive community mental health center providing mental health and substance use disorder services to the residents of Wasatch County. WCFC-WBH provides a mental health and Substance Use screening to any Wasatch County resident requesting services. Based on available resources, (funding or otherwise), prospective clients will be referred to or linked with available resources. Medicaid eligible clients will be provided access to the full array of services available. Individuals who carry commercial insurance will be seen as their benefits allow. Clients with no funding may be seen on a sliding fee scale. Who is eligible to receive substance abuse services within your catchment area? What services (are there different services available depending on funding)? Identify how you manage wait lists. How do you ensure priority populations get served? WCFC-WBH provides substance abuse services to residents of Wasatch County. Medicaid and commercial insurances are also accepted and services are provided as benefits allow. WCFC-WBH provides substance abuse services as funding allows those without insurance or ability to pay. A sliding fee scale is available for these clients. Clients accepted into the drug court also have all services available and fees are also set based on the sliding scale. -

Teacher's Manual

Teacher’s Manual The goal of this manual is to assist teacher and student to better understand the his- tory of the Oregon/California Trail before your visit to The National Oregon/California Trail Center, especially as this information relates to Idaho's western heritage. 2009 Student Outreach Program Sponsors: All rights reserved by Oregon Trail Center, Inc. All pages may be reproduced for classroom instruction and not for commercial profit. Teacher's Resource Manual Table of Contents Quick Preview of The National Oregon/California Trail Center……………... Page 3, 4 History of Bear Lake Valley, Idaho……………………………………………... Page 5 Oregon Trail Timeline……………………………………………………………. Page 6 What Can I Take on the Trail?...................................................................... Page 7 How Much Will This Trip Cost?..................................................................... Page 7 Butch Cassidy and the Bank of Montpelier……………………………………. Page 8 Factoids and Idaho Trail Map…………………………………………… ……... Page 9 Bibliography of Oregon Trail Books (compiled by Bear Lake County Library)……………. Page 10-11 Fun Activities: Oregon Trail Timeline Crossword Puzzle (Relates to Page 5)……………… Page 12-14 Oregon Trail Word Search…………………………………………….………... Page 15-16 Web Site Resources: www.oregontrailcenter.org - The National Oregon/California Trail Center www.bearlake.org - Bear Lake Convention & Visitor's Bureau (accommodations) www.bearlakechamber.org - Greater Bear Lake Valley Chamber of Commerce www.bearlakecounty.info - County of Bear Lake, Idaho www.montpelieridaho.info - Montpelier, Idaho bearlake.lili.org - Bear Lake County Library 2 Quick Preview of . Clover Creek Encampment The Center actually sits on the very spot used as the historic Clover Creek Encampment. Travelers would camp overnight and some- times for days resting their animals, stocking up on food and water, and preparing for the next leg of the journey. -

Geology and Mineral Resources of the Randolph Quadrangle, Utah -Wyoming

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Harold L. Ickes, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. C. Mendenhall, Director Bulletin 923 GEOLOGY AND MINERAL RESOURCES OF THE RANDOLPH QUADRANGLE, UTAH -WYOMING BY G. B. RICHARDSON UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1941 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. O. ......... Price 55 cents HALL LIBRARY CONTENTS Pag* Abstract.____________--__-_-_-___-___-_---------------__----_____- 1 Introduction- ____________-__-___---__-_-_---_-_-----_----- -_______ 1 Topography. _____________________________________________________ 3 Bear River Range._.___---_-_---_-.---.---___-___-_-__________ 3 Bear River-Plateau___-_-----_-___-------_-_-____---___________ 5 Bear Lake-Valley..-_--_-._-_-__----__----_-_-__-_----____-____- 5 Bear River Valley.___---------_---____----_-_-__--_______'_____ 5 Crawford Mountains .________-_-___---____:.______-____________ 6 Descriptive geology.______-_____-___--__----- _-______--_-_-________ 6 Stratigraphy _ _________________________________________________ 7 Cambrian system.__________________________________________ 7 Brigham quartzite.____________________________________ 7 Langston limestone.___________________________________ 8 Ute limestone.__----_--____-----_-___-__--___________. 9 Blacksmith limestone._________________________________ 10 Bloomington formation..... _-_-_--___-____-_-_____-____ 11 Nounan limestone. _______-________ ____________________ 12 St. Charles limestone.. ---_------------------_--_-.-._ 13 Ordovician system._'_____________.___.__________________^__ -

Logan Canyon

C A C H E V A L L E Y / B E A R L A K E Guide to the LOGAN CANYON NATIONAL SCENIC BYWAY 1 explorelogan.com C A C H E V A L L E Y / B E A R L A K E 31 SITES AND STOPS TABLE OF CONTENTS Site 1 Logan Ranger District 4 31 Site 2 Canyon Entrance 6 Site 3 Stokes Nature Center / River Trail 7 hether you travel by car, bicycle or on foot, a Site 4 Logan City Power Plant / Second Dam 8 Wjourney on the Logan Canyon National Scenic Site 5 Bridger Campground 9 Byway through the Wasatch-Cache National Forest Site 6 Spring Hollow / Third Dam 9 Site 7 Dewitt Picnic Area 10 offers an abundance of breathtaking natural beauty, Site 8 Wind Caves Trailhead 11 diverse recreational opportunities, and fascinating Site 9 Guinavah-Malibu 12 history. This journey can calm your heart, lift your Site 10 Card Picnic Area 13 Site 11 Chokecherry Picnic Area 13 spirit, and create wonderful memories. Located Site 12 Preston Valley Campground 14 approximately 90 miles north of Salt Lake City, this Site 13 Right Hand Fork / winding stretch of U.S. Hwy. 89 runs from the city of Lodge Campground 15 Site 14 Wood Camp / Jardine Juniper 16 Logan in beautiful Cache Valley to Garden City on Site 15 Logan Cave 17 the shores of the brilliant azure-blue waters of Bear Site 16 The Dugway 18 Lake. It passes through colorful fields of wildflowers, Site 17 Blind Hollow Trailhead 19 Site 18 Temple Fork / Old Ephraim’s Grave 19 between vertical limestone cliffs, and along rolling Site 19 Ricks Spring 21 streams brimming with trout. -

Lake Bonneville: Geology of Southern Cache Valley, Utah

Lake Bonneville: i Geology of Southern Cache Valley, Utah GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 257-C Lake Bonneville: Geology of Southern Cache Valley, Utah By J. STEWART WILLIAMS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 257-C Cenozoic geology of a part of the area inundated by a late Pleistocene lake UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1962 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STEWART L. UDALL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D.C. CONTENTS Page Page Abstract-__-_-__-____-_____--_-_-_-________-_-_____ 131 Stratigraphy—Continued Introduction.______________________________________ 131 Quaternary deposits—Continued Stratigraphy.______________________________________ 132 Landslides of Lake Bonneville and post-Lake Pre-Tertiary rocks_______-_-_-_-_-_-_.__________ 132 Bonneville age____________________________ 142 Tertiary system. _______________________________ 132 Post-Lake Bonneville deposits________________ 142 Wasatch formation__________________________ 132 Fan graveL____________________________ 142 Salt Lake formation...______________________ 133 Flood-plan alluvium_____________________ 142 Lower conglomerate unit________________ 133 Alluvial sand in natural levees of the Bear Tuff unit.---_-----_---------------_--_ 134 River----.-----------.-------------- 142 Upper conglomerate and sandstone unit___ 134 Slope wash___________________________ 143 Quaternary deposits.._____---____-__--_____-___- 135 Eolian -

Utah Reclamation Mitigation & Conservation Commission FY2016

UTAH RECLAMATION MITIGATION & CONSERVATION COMMISSION FY2016-2018 Report Introduction Contents Welcome to the FY2016-2018 Report of the Utah Reclamation Mitigation and Conservation Commission (Mitigation Meet the Mitigation Commission ........... Page 1 Commission). The Mitigation Commission was authorized and established by Congress and the President in 1992 through the Program Elements Map ........................ Page 2-3 Central Utah Project Completion Act (CUPCA; Titles II through VI Lower Provo River/Utah Lake.................. Page 4 of Public Law 102-575). The Mitigation Commission’s primary responsibility is to plan, coordinate and fund programs to mitigate Middle and Upper Provo River ............... Page 6 for adverse effects of the Bonneville Unit of the Central Utah Diamond Fork Watershed ....................... Page 8 Project on fish, wildlife and related recreation resources in Utah. This report highlights Mitigation Commission accomplishments for Strawberry/Duchesne Watershed ........ Page 12 fiscal years 2016 through 2018, and describes the effectiveness of Great Salt Lake/Jordan River ............... Page 14 those actions toward achieving CUPCA requirements. It also identifies actions planned for the foreseeable future and Statewide ................................................ Page 16 potential revisions to our Mitigation and Conservation Plan. In our Office ............................................ Page 17 By design, the Mitigation Commission’s program relies on FY2016-2018 Financial Report ............... Page 17 partnerships with the larger natural resource community. The Mitigation Commission forms partnerships with natural resource Our Partners ...................................... back cover agencies, State and local governments, Indian tribes, universities and non-profit organizations, to carry out its many projects in a coordinated and cooperative manner. Therefore, throughout this report, the term “we” is intended to include the many partners essential to moving Mitigation Commission projects forward. -

Bonneville Cutthroat Trout (Oncorhynchus Clarki Utah)

Bonneville Cutthroat Trout (Oncorhynchus clarki utah) Data: Range-wide Status (May and Albeke 2005) - Updated in 2010 and 2015 Partners: Bureau of Land Management, Confederated Tribes of the Goshute Reservation, Idaho Game and Fish Department, National Park Service, Nevada Department of Wildlife, Trout Unlimited, Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, Wyoming Game and Fish Department, US Fish and Wildlife Service, US Forest Service, Utah Reclamation Mitigation and Conservation Commission ii | Western Native Trout Status Report - Updated January 2018 Species Status Review to catch, and most populations are managed through the use of fishing regulations that The Bonneville Cutthroat Trout (BCT) is protect population integrity and viability. In ad- listed as a “Tier I Conservation Species” by the dition, many BCT populations occur in remote State of Utah, as a “Sensitive Species” by the locations and receive limited fishing pressure US Forest Service, as a “Rangewide Imperiled making special regulations unnecessary. Due (Type 2) Species” by the Bureau of Land Man- to protective regulations and/or the occurrence agement, and as a “Vulnerable Species” by the of BCT in remote areas, over-fishing is not State of Idaho. This species has been petitioned considered to be a problem at this time. Short- for, but precluded for, listing as Threatened or term fishing closures are often imposed to Endangered by the US Fish and Wildlife Ser- promote the development of recently re-intro- vice several times in the past decade. The most duced populations of BCT. Spawning season recent determination, that the species does not closures are frequently used, particularly for warrant listing as a threatened or endangered brood populations. -

Wasatch Mental Health

GOVERNANCE & OVERSIGHT NARRATIVE Local Authority: Wasatch Behavioral Health Special Service District Instructions: In the cells below, please provide an answer/description for each question. PLEASE CHANGE THE COLOR OF SUBSTANTIVE NEW LANGUAGE INCLUDED IN YOUR PLAN THIS YEAR! 1) Access & Eligibility for Mental Health and/or Substance Abuse Clients Who is eligible to receive mental health services within your catchment area? What services (are there different services available depending on funding)? Wasatch Behavioral Health Special Service District (WBH) is a comprehensive community mental health and substance use disorder center providing a full array of mental health and substance use disorder services to the residents of Utah County. WBH provides a mental health and substance use disorder screening to any Utah County resident in need for mental health and substance use disorder services. The screening is to assess the level of care and appropriate services either through WBH or a referral to the appropriate outside provider/agency. Based on available resources, (funding or otherwise), prospective clients will be referred to or linked with available resources. Medicaid eligible clients will be provided access to the full array of services available. Individuals who carry commercial insurance will be referred to appropriate providers in the community or referred to one of the many programs within WBH for treatment based on eligibility. Additionally, WBH has several specialized programs, including a specialized program for children and youth with autism spectrum disorders, treatment for adjudicated youth sex offenders, residential and youth receiving services, individuals who are homeless, clients who are treated by the mental health court or drug court, and other services for members of the community who are unable to afford treatment. -

6-Public Comments April May 2020 Re Provo River Trail

Date received Name Representing Comment Additional comment April 28, 2020 Brad Tanner I support the the expansion of the Provo Trail beyond Vivian Park. April 28, 2020 Austin Taylor Transportation Commission Members I am emailing to voice my support for the expansion of the Provo River Trail at $6.1 million. These trying times have shown us how important trails are to the mental and physical health of our communities. The Murdock Canal Trail in Utah County has seen an increase of 80% in ridership compared to this time last year because people need outdoor activity to stay healthy. This expansion will give people an opportunity to explore more of nature and improve their physical and mental health. It may also benefit the economies of the Provo and Heber City areas as people ride bikes between the two areas to shop, dine, and recreate. I do this with my wife on bike tours through Provo Canyon but we are crazy and willing to take a risk riding on the highway. Lastly, this project will enhance safety for cyclists on the route. People are currently biking on the debris-filled shoulders of a 55mph highway with 17,000 trips per day. While some road cyclists choose to take the risks, the vast majority of people who bike avoid it. Expanding the river trail would make riding in this area safer and expand this opportunity to more people. -- Austin Taylor April 28, 2020 Doug Smith Wasatch To Whom It May Concern, County Planning I am writing this e-mail in support of the funding for the Provo Canyon Trail from Vivian Park to the Deer Creek Dam. -

Bear Lake and Its Future

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DigitalCommons@USU Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Faculty Honor Lectures Lectures 5-1-1962 Bear Lake and its Future William F. Sigler Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honor_lectures Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Sigler, William F., "Bear Lake and its Future" (1962). Faculty Honor Lectures. Paper 22. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honor_lectures/22 This Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by the Lectures at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Honor Lectures by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I I' l ! t ,I I The author is deeply indebted to Lois Cox for her help throughout the paper. - TWENTY-SIXTH FACULTY HONOR LECTURE i BEAR LAKE , AND ITS FUTURE by WILLIAM F. SIGLER Professor of Wildlife Resources I THE FACULTY ASSOCIATION UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY LOGAN UTAH 1962 TO DINGLE TO MONTPELIER .. I NORTH FORK ST. ST. CHARLES ·SCOUT CAMP :NEBECKER LAKOTA SWAN CREEK EDEN CREEK SCOUT CAMP HUNT GARDEN C"-IT_Y_-........ TO LOGA ~ SOUTH EDEN CREEk _____...---'71 / t LAKETOWN BEAR LAKE UTAH - IDAHO MAXIMUM ELEVATION - 5923.6 FT. ABOVE SEA LEVEL SCALE I INCH = 4 MILES SURFACED ROADS SHORELINE DISTANCE - 4 e M ILES IMPROVED ROADS SURFACE AREA - 109 SQ. MILES DIRT ROADS BEAR LAKE AND ITS FUTURE by William F. Sigler ven in such a wide-ranging and eternally changing field as biology, Ea few statements about certain aspects can be made with a mini mum likelihood of their being refuted. -

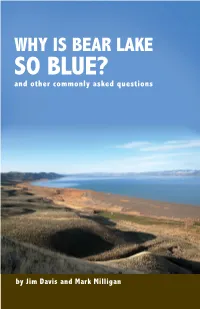

WHY IS BEAR LAKE SO BLUE? and Other Commonly Asked Questions

WHY IS BEAR LAKE SO BLUE? and other commonly asked questions by Jim Davis and Mark Milligan CONTENTS INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................................................2 WHERE IS BEAR LAKE? ...................................................................................................................4 WHY IS THERE A BIG, DEEP LAKE HERE? ..............................................................................6 WHY IS BEAR LAKE SO BLUE? ................................................................................................... 10 WHAT IS THE SHORELINE LIKE? ............................................................................................. 12 WHEN WAS BEAR LAKE DISCOVERED AND SETTLED? ................................................. 15 HOW OLD IS BEAR LAKE? ............................................................................................................16 WHEN DID THE BEAR RIVER AND BEAR LAKE MEET? ................................................ 17 WHAT LIVES IN BEAR LAKE? ..................................................................................................... 20 DOES BEAR LAKE FREEZE? .........................................................................................................24 WHAT IS THE WEATHER AT BEAR LAKE? .......................................................................... 26 WHAT DID BEAR LAKE LOOK LIKE DURING THE ICE AGE? .........................................28 WHAT IS KARST?.............................................................................................................................