Linkers Part 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to Computer Systems 15-213/18-243, Spring 2009 1St

M4-L3: Executables CSE351, Winter 2021 Executables CSE 351 Winter 2021 Instructor: Teaching Assistants: Mark Wyse Kyrie Dowling Catherine Guevara Ian Hsiao Jim Limprasert Armin Magness Allie Pfleger Cosmo Wang Ronald Widjaja http://xkcd.com/1790/ M4-L3: Executables CSE351, Winter 2021 Administrivia ❖ Lab 2 due Monday (2/8) ❖ hw12 due Friday ❖ hw13 due next Wednesday (2/10) ▪ Based on the next two lectures, longer than normal ❖ Remember: HW and readings due before lecture, at 11am PST on due date 2 M4-L3: Executables CSE351, Winter 2021 Roadmap C: Java: Memory & data car *c = malloc(sizeof(car)); Car c = new Car(); Integers & floats c->miles = 100; c.setMiles(100); x86 assembly c->gals = 17; c.setGals(17); Procedures & stacks float mpg = get_mpg(c); float mpg = Executables free(c); c.getMPG(); Arrays & structs Memory & caches Assembly get_mpg: Processes pushq %rbp language: movq %rsp, %rbp Virtual memory ... Memory allocation popq %rbp Java vs. C ret OS: Machine 0111010000011000 100011010000010000000010 code: 1000100111000010 110000011111101000011111 Computer system: 3 M4-L3: Executables CSE351, Winter 2021 Reading Review ❖ Terminology: ▪ CALL: compiler, assembler, linker, loader ▪ Object file: symbol table, relocation table ▪ Disassembly ▪ Multidimensional arrays, row-major ordering ▪ Multilevel arrays ❖ Questions from the Reading? ▪ also post to Ed post! 4 M4-L3: Executables CSE351, Winter 2021 Building an Executable from a C File ❖ Code in files p1.c p2.c ❖ Compile with command: gcc -Og p1.c p2.c -o p ▪ Put resulting machine code in -

The GNU Linker

The GNU linker ld (GNU Binutils) Version 2.37 Steve Chamberlain Ian Lance Taylor Red Hat Inc [email protected], [email protected] The GNU linker Edited by Jeffrey Osier ([email protected]) Copyright c 1991-2021 Free Software Foundation, Inc. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.3 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, with no Front-Cover Texts, and with no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled \GNU Free Documentation License". i Table of Contents 1 Overview :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 1 2 Invocation ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 3 2.1 Command-line Options ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 3 2.1.1 Options Specific to i386 PE Targets :::::::::::::::::::::: 40 2.1.2 Options specific to C6X uClinux targets :::::::::::::::::: 47 2.1.3 Options specific to C-SKY targets :::::::::::::::::::::::: 48 2.1.4 Options specific to Motorola 68HC11 and 68HC12 targets :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 48 2.1.5 Options specific to Motorola 68K target :::::::::::::::::: 48 2.1.6 Options specific to MIPS targets ::::::::::::::::::::::::: 49 2.1.7 Options specific to PDP11 targets :::::::::::::::::::::::: 49 2.2 Environment Variables :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 50 3 Linker Scripts:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 51 3.1 Basic Linker Script Concepts :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 51 3.2 Linker Script -

CERES Software Bulletin 95-12

CERES Software Bulletin 95-12 Fortran 90 Linking Experiences, September 5, 1995 1.0 Purpose: To disseminate experience gained in the process of linking Fortran 90 software with library routines compiled under Fortran 77 compiler. 2.0 Originator: Lyle Ziegelmiller ([email protected]) 3.0 Description: One of the summer students, Julia Barsie, was working with a plot program which was written in f77. This program called routines from a graphics package known as NCAR, which is also written in f77. Everything was fine. The plot program was converted to f90, and a new version of the NCAR graphical package was released, which was written in f77. A problem arose when trying to link the new f90 version of the plot program with the new f77 release of NCAR; many undefined references were reported by the linker. This bulletin is intended to convey what was learned in the effort to accomplish this linking. The first step I took was to issue the "-dryrun" directive to the f77 compiler when using it to compile the original f77 plot program and the original NCAR graphics library. "- dryrun" causes the linker to produce an output detailing all the various libraries that it links with. Note that these libaries are in addition to the libaries you would select on the command line. For example, you might compile a program with erbelib, but the linker would have to link with librarie(s) that contain the definitions of sine or cosine. Anyway, it was my hypothesis that if everything compiled and linked with f77, then all the libraries must be contained in the output from the f77's "-dryrun" command. -

The “Stabs” Debug Format

The \stabs" debug format Julia Menapace, Jim Kingdon, David MacKenzie Cygnus Support Cygnus Support Revision TEXinfo 2017-08-23.19 Copyright c 1992{2021 Free Software Foundation, Inc. Contributed by Cygnus Support. Written by Julia Menapace, Jim Kingdon, and David MacKenzie. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.3 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, with no Front-Cover Texts, and with no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled \GNU Free Documentation License". i Table of Contents 1 Overview of Stabs ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 1 1.1 Overview of Debugging Information Flow ::::::::::::::::::::::: 1 1.2 Overview of Stab Format ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 1 1.3 The String Field :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 2 1.4 A Simple Example in C Source ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 3 1.5 The Simple Example at the Assembly Level ::::::::::::::::::::: 4 2 Encoding the Structure of the Program ::::::: 7 2.1 Main Program :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 7 2.2 Paths and Names of the Source Files :::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 7 2.3 Names of Include Files:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 8 2.4 Line Numbers :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 9 2.5 Procedures ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 9 2.6 Nested Procedures::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 11 2.7 Block Structure -

Doin' the Eagle Rock

VIRUS BULLETIN www.virusbtn.com MALWARE ANALYSIS 1 DOIN’ THE EAGLE ROCK this RNG in every virus for which he requires a source of random numbers. Peter Ferrie Microsoft, USA The virus then allocates two blocks of memory: one to hold the intermediate encoding of the virus body, and the other to hold the fully encoded virus body. The virus decompresses If a fi le contains no code, can it be executed? Can arithmetic a fi le header into the second block. The fi le header is operations be malicious? Here we have a fi le that contains compressed using a simple Run-Length Encoder algorithm. no code, and no data in any meaningful sense. All it The header is for a Windows Portable Executable fi le, and it contains is a block of relocation items, and all relocation seems as though the intention was to produce the smallest items do is cause a value to be added to locations in the possible header that can still be executed on Windows. There image. So, nothing but relocation items – and yet it also are overlapping sections, and ‘unnecessary’ fi elds have been contains W32/Lerock. removed. The virus then allocates a third block of memory, Lerock is written by the same virus author as W32/Fooper which will hold a copy of the unencoded virus body. (see VB, January 2010, p.4), and behaves in the same way at a The virus searches for zeroes within the unencoded memory high level, but at a lower level it differs in an interesting way. -

Linking + Libraries

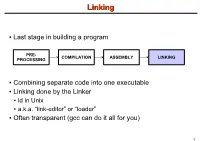

LinkingLinking ● Last stage in building a program PRE- COMPILATION ASSEMBLY LINKING PROCESSING ● Combining separate code into one executable ● Linking done by the Linker ● ld in Unix ● a.k.a. “link-editor” or “loader” ● Often transparent (gcc can do it all for you) 1 LinkingLinking involves...involves... ● Combining several object modules (the .o files corresponding to .c files) into one file ● Resolving external references to variables and functions ● Producing an executable file (if no errors) file1.c file1.o file2.c gcc file2.o Linker Executable fileN.c fileN.o Header files External references 2 LinkingLinking withwith ExternalExternal ReferencesReferences file1.c file2.c int count; #include <stdio.h> void display(void); Compiler extern int count; int main(void) void display(void) { file1.o file2.o { count = 10; with placeholders printf(“%d”,count); display(); } return 0; Linker } ● file1.o has placeholder for display() ● file2.o has placeholder for count ● object modules are relocatable ● addresses are relative offsets from top of file 3 LibrariesLibraries ● Definition: ● a file containing functions that can be referenced externally by a C program ● Purpose: ● easy access to functions used repeatedly ● promote code modularity and re-use ● reduce source and executable file size 4 LibrariesLibraries ● Static (Archive) ● libname.a on Unix; name.lib on DOS/Windows ● Only modules with referenced code linked when compiling ● unlike .o files ● Linker copies function from library into executable file ● Update to library requires recompiling program 5 LibrariesLibraries ● Dynamic (Shared Object or Dynamic Link Library) ● libname.so on Unix; name.dll on DOS/Windows ● Referenced code not copied into executable ● Loaded in memory at run time ● Smaller executable size ● Can update library without recompiling program ● Drawback: slightly slower program startup 6 LibrariesLibraries ● Linking a static library libpepsi.a /* crave source file */ … gcc .. -

Using the DLFM Package on the Cray XE6 System

Using the DLFM Package on the Cray XE6 System Mike Davis, Cray Inc. Version 1.4 - October 2013 1.0: Introduction The DLFM package is a set of libraries and tools that can be applied to a dynamically-linked application, or an application that uses Python, to provide improved performance during the loading of dynamic libraries and importing of Python modules when running the application at large scale. Included in the DLFM package are: a set of wrapper functions that interface with the dynamic linker (ld.so) to cache the application's dynamic library load operations; and a custom libpython.so, with a set of optimized components, that caches the application's Python import operations. 2.0: Dynamic Linking and Python Importing Without DLFM When a dynamically-linked application is executed, the set of dependent libraries is loaded in sequence by ld.so prior to the transfer of control to the application's main function. This set of dependent libraries ordinarily numbers a dozen or so, but can number many more, depending on the needs of the application; their names and paths are given by the ldd(1) command. As ld.so processes each dependent library, it executes a series of system calls to find the library and make the library's contents available to the application. These include: fd = open (/path/to/dependent/library, O_RDONLY); read (fd, elfhdr, 832); // to get the library ELF header fstat (fd, &stbuf); // to get library attributes, such as size mmap (buf, length, prot, MAP_PRIVATE, fd, offset); // read text segment mmap (buf, length, prot, MAP_PRIVATE, fd, offset); // read data segment close (fd); The number of open() calls can be many times larger than the number of dependent libraries, because ld.so must search for each dependent library in multiple locations, as described on the ld.so(1) man page. -

Portable Executable File Format

Chapter 11 Portable Executable File Format IN THIS CHAPTER + Understanding the structure of a PE file + Talking in terms of RVAs + Detailing the PE format + The importance of indices in the data directory + How the loader interprets a PE file MICROSOFT INTRODUCED A NEW executable file format with Windows NT. This for- mat is called the Portable Executable (PE) format because it is supposed to be portable across all 32-bit operating systems by Microsoft. The same PE format exe- cutable can be executed on any version of Windows NT, Windows 95, and Win32s. Also, the same format is used for executables for Windows NT running on proces- sors other than Intel x86, such as MIPS, Alpha, and Power PC. The 32-bit DLLs and Windows NT device drivers also follow the same PE format. It is helpful to understand the PE file format because PE files are almost identi- cal on disk and in RAM. Learning about the PE format is also helpful for under- standing many operating system concepts. For example, how operating system loader works to support dynamic linking of DLL functions, the data structures in- volved in dynamic linking such as import table, export table, and so on. The PE format is not really undocumented. The WINNT.H file has several struc- ture definitions representing the PE format. The Microsoft Developer's Network (MSDN) CD-ROMs contain several descriptions of the PE format. However, these descriptions are in bits and pieces, and are by no means complete. In this chapter, we try to give you a comprehensive picture of the PE format. -

Architectural Support for Dynamic Linking Varun Agrawal, Abhiroop Dabral, Tapti Palit, Yongming Shen, Michael Ferdman COMPAS Stony Brook University

Architectural Support for Dynamic Linking Varun Agrawal, Abhiroop Dabral, Tapti Palit, Yongming Shen, Michael Ferdman COMPAS Stony Brook University Abstract 1 Introduction All software in use today relies on libraries, including All computer programs in use today rely on software standard libraries (e.g., C, C++) and application-specific libraries. Libraries can be linked dynamically, deferring libraries (e.g., libxml, libpng). Most libraries are loaded in much of the linking process to the launch of the program. memory and dynamically linked when programs are Dynamically linked libraries offer numerous benefits over launched, resolving symbol addresses across the applica- static linking: they allow code reuse between applications, tions and libraries. Dynamic linking has many benefits: It conserve memory (because only one copy of a library is kept allows code to be reused between applications, conserves in memory for all applications that share it), allow libraries memory (because only one copy of a library is kept in mem- to be patched and updated without modifying programs, ory for all the applications that share it), and allows enable effective address space layout randomization for libraries to be patched and updated without modifying pro- security [21], and many others. As a result, dynamic linking grams, among numerous other benefits. However, these is the predominant choice in all systems today [7]. benefits come at the cost of performance. For every call To facilitate dynamic linking of libraries, compiled pro- made to a function in a dynamically linked library, a trampo- grams include function call trampolines in their binaries. line is used to read the function address from a lookup table When a program is launched, the dynamic linker maps the and branch to the function, incurring memory load and libraries into the process address space and resolves external branch operations. -

Common Object File Format (COFF)

Application Report SPRAAO8–April 2009 Common Object File Format ..................................................................................................................................................... ABSTRACT The assembler and link step create object files in common object file format (COFF). COFF is an implementation of an object file format of the same name that was developed by AT&T for use on UNIX-based systems. This format encourages modular programming and provides powerful and flexible methods for managing code segments and target system memory. This appendix contains technical details about the Texas Instruments COFF object file structure. Much of this information pertains to the symbolic debugging information that is produced by the C compiler. The purpose of this application note is to provide supplementary information on the internal format of COFF object files. Topic .................................................................................................. Page 1 COFF File Structure .................................................................... 2 2 File Header Structure .................................................................. 4 3 Optional File Header Format ........................................................ 5 4 Section Header Structure............................................................. 5 5 Structuring Relocation Information ............................................... 7 6 Symbol Table Structure and Content........................................... 11 SPRAAO8–April 2009 -

CS429: Computer Organization and Architecture Linking I & II

CS429: Computer Organization and Architecture Linking I & II Dr. Bill Young Department of Computer Sciences University of Texas at Austin Last updated: April 5, 2018 at 09:23 CS429 Slideset 23: 1 Linking I A Simplistic Translation Scheme m.c ASCII source file Problems: Efficiency: small change Compiler requires complete re-compilation. m.s Modularity: hard to share common functions (e.g., printf). Assembler Solution: Static linker (or Binary executable object file linker). p (memory image on disk) CS429 Slideset 23: 2 Linking I Better Scheme Using a Linker Linking is the process of m.c a.c ASCII source files combining various pieces of code and data into a Compiler Compiler single file that can be loaded (copied) into m.s a.s memory and executed. Linking could happen at: Assembler Assembler compile time; Separately compiled m.o a.o load time; relocatable object files run time. Linker (ld) Must somehow tell a Executable object file module about symbols p (code and data for all functions defined in m.c and a.c) from other modules. CS429 Slideset 23: 3 Linking I Linking A linker takes representations of separate program modules and combines them into a single executable. This involves two primary steps: 1 Symbol resolution: associate each symbol reference throughout the set of modules with a single symbol definition. 2 Relocation: associate a memory location with each symbol definition, and modify each reference to point to that location. CS429 Slideset 23: 4 Linking I Translating the Example Program A compiler driver coordinates all steps in the translation and linking process. -

Tricore Architecture Manual for a Detailed Discussion of Instruction Set Encoding and Semantics

User’s Manual, v2.3, Feb. 2007 TriCore 32-bit Unified Processor Core Embedded Applications Binary Interface (EABI) Microcontrollers Edition 2007-02 Published by Infineon Technologies AG 81726 München, Germany © Infineon Technologies AG 2007. All Rights Reserved. Legal Disclaimer The information given in this document shall in no event be regarded as a guarantee of conditions or characteristics (“Beschaffenheitsgarantie”). With respect to any examples or hints given herein, any typical values stated herein and/or any information regarding the application of the device, Infineon Technologies hereby disclaims any and all warranties and liabilities of any kind, including without limitation warranties of non- infringement of intellectual property rights of any third party. Information For further information on technology, delivery terms and conditions and prices please contact your nearest Infineon Technologies Office (www.infineon.com). Warnings Due to technical requirements components may contain dangerous substances. For information on the types in question please contact your nearest Infineon Technologies Office. Infineon Technologies Components may only be used in life-support devices or systems with the express written approval of Infineon Technologies, if a failure of such components can reasonably be expected to cause the failure of that life-support device or system, or to affect the safety or effectiveness of that device or system. Life support devices or systems are intended to be implanted in the human body, or to support and/or maintain and sustain and/or protect human life. If they fail, it is reasonable to assume that the health of the user or other persons may be endangered. User’s Manual, v2.3, Feb.