Membranes for Water Treatment: Reverse Osmosis and Nanofiltration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Water Treatment and Reverse Osmosis Systems

Pure Aqua, Inc.® Water© 2012 TreatmentPure Aqua ,and Inc. ReverseAll Right sOsmosis Reserve dSystems. Worldwide Experience Superior Technology About the Company Pure Aqua is a company with a strong philosophy and drive to develop and apply solutions to the world’s water treatment challenges. We believe that both our technology and experience will help resolve the growing shortage of clean water worldwide. Capabilities and Expertise As an ISO 9001:2008 certified company with over a decade of experience, Pure Aqua has secured its position as a leading manufacturer of reverse osmosis systems worldwide. Goals and Motivations Our goal is to provide environmentally sustainable systems and equipment that produce high quality water. We provide packaged systems and technical support for water treatment plants, industrial wastewater reuse, and brackish and seawater reverse osmosis plants. Having strong working relationships with Thus, we ensure our technological our suppliers gives us the capability to contribution to water preservation by provide cost effective and competitive supplying the means and making it highly water and wastewater treatment systems accessible. for a wide range of applications. Seawater Reverse Osmosis Systems System Overview Designed to convert seawater to potable water, desalination systems use high quality reverse osmosis seawater membranes. The process separates dissolved salts by only allowing pure water to pass through the membrane fabric. System Capacities Pure Aqua desalination systems are designed to provide high -

Development of Polymeric Membranes for Oil/Water Separation

membranes Article Development of Polymeric Membranes for Oil/Water Separation Arshad Hussain and Mohammed Al-Yaari * Chemical Engineering Department, King Faisal University, P.O. Box 380, Al-Ahsa 31982, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +966-13-589-8583 Abstract: In this work, the treatment of oily wastewater was investigated using developed cellulose acetate (CA) membranes blended with Nylon 66. Membrane characterization and permeation results in terms of oil rejection and flux were compared with a commercial CA membrane. The solution casting method was used to fabricate membranes composed of CA and Nylon 66. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) analysis was done to examine the surface morphology of the membrane as well as the influence of solvent on the overall structure of the developed membranes. Mechanical and thermal properties of developed blended membranes and a commercial membrane were examined by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and universal (tensile) testing machine (UTM). Membrane characterizations revealed that the thermal and mechanical properties of the fabricated blended membranes better than those of the commercial membrane. Membrane fluxes and rejection of oil as a function of Nylon 66 compositions and transmembrane pressure were measured. Experimental results revealed that the synthetic membrane (composed of 2% Nylon 66 and Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) as a solvent) gave a permeate flux of 33 L/m2h and an oil rejection of around 90%, whereas the commercial membrane showed a permeate flux of 22 L/m2h and an oil rejection of 70%. Keywords: oil–water separation; polymeric membrane; cellulose acetate; Nylon 66; permeability Citation: Hussain, A.; Al-Yaari, M. -

Reverse Osmosis and Nanofiltration, Second Edition

Reverse Osmosis and Nanofiltration AWWA MANUAL M46 Second Edition Science and Technology AWWA unites the entire water community by developing and distributing authoritative scientific and technological knowledge. Through its members, AWWA develops industry standards for products and processes that advance public health and safety. AWWA also provides quality improvement programs for water and wastewater utilities. Copyright © 2007 American Water Works Association. All Rights Reserved. Contents List of Figures, v List of Tables, ix Preface, xi Acknowledgments, xiii Chapter 1 Introduction . 1 Overview, 1 RO and NF Membrane Applications, 7 Membrane Materials and Configurations, 12 References, 18 Chapter 2 Process Design . 21 Source Water Supply, 21 Pretreatment, 26 Membrane Process Theory, 45 Rating RO and NF Elements, 51 Posttreatment, 59 References, 60 Chapter 3 Facility Design and Construction . 63 Raw Water Intake Facilities, 63 Discharge, 77 Suspended Solids and Silt Removal Facilities, 80 RO and NF Systems, 92 Hydraulic Turbochargers, 95 Posttreatment Systems, 101 Ancillary Equipment and Facilities, 107 Instrumentation and Control Systems, 110 Waste Stream Management Facilities, 116 Other Concentrate Management Alternatives, 135 Disposal Alternatives for Waste Pretreatment Filter Backwash Water, 138 General Treatment Plant Design Fundamentals, 139 Plant Site Location and Layout, 139 General Plant Layout Considerations, 139 Membrane System Layout Considerations, 140 Facility Construction and Equipment Installation, 144 General Guidelines for Equipment Installation, 144 Treatment Costs, 151 References, 162 iii Copyright © 2007 American Water Works Association. All Rights Reserved. Chapter 4 Operations and Maintenance . 165 Introduction, 165 Process Monitoring, 168 Biological Monitoring, 182 Chemical Cleaning, 183 Mechanical Integrity, 186 Instrumentation Calibration, 188 Safety, 190 Appendix A SI Equivalent Units Conversion Tables . -

Electrocoagulation Pretreatment for Microfiltration: an Innovative Combination to Enhance Water Quality and Reduce Fouling in Integrated Membrane Systems

Desalination and Water Purification Research and Development Report No. 139 Electrocoagulation Pretreatment for Microfiltration: An Innovative Combination to Enhance Water Quality and Reduce Fouling in Integrated Membrane Systems University of Houston U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Technical Service Center Denver, Colorado September 2007 Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 The public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing the burden, to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 2. REPORT TYPE 1. REPORT DATE (DD-MM-YYYY) 3. DATES COVERED (From - To) Final September 2007 October 2005 – September 2007 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER Electrocoagulation Pretreatment for Microfiltration: An Innovative Combination Agreement No. 05-FC-81-1172 to Enhance Water Quality and Reduce Fouling in Integrated Membrane Systems 5b. GRANT NUMBER 5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER 6. AUTHOR(S) 5d. PROJECT NUMBER Shankar Chellam, Principal Investigator Dennis A. -

Dynamic Modeling of Multi Stage Flash (MSF) Desalination Plant

Dynamic Modeling of Multi Stage Flash (MSF) Desalination Plant by Hala Faisal Al-Fulaij Department of Chemical Engineering University College London Supervisors: Professor David Bogle Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) at University College London (UCL) July 2011 I, Hala Faisal Al-Fulaij, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Hala F. Al-Fulaij Acknowledgments i Acknowledgments This Ph.D. was carried out between March 2007 and January 2011 at the Chemical Engineering department, University College London (UCL). This work was supervised by Professor David Bogle (UCL) and Professor Hisham Ettouney (Kuwait University). I take this opportunity to thank both of my supervisors for general guidance throughout the project and their great help, support and insight. I also thank Professor Giorgio Micale and Doctor Andrea Cipollina from University of Palermo who expended their time and made significant contribution to my knowledge especially in the computer tools field. Also, I am grateful for the love and support of my family, especially my mother, father, husband and sisters. Their patience and encouragement have given me the strength to complete my thesis study. Finally I would like to dedicate this thesis to my lovely children (Rayan, Maryam, AbdulWahab and Najat) hoping them the most of health, success, and happiness. Abstract ii Abstract The world population is increasing at a very rapid rate while the natural water resources remain constant. During the past decades industrial desalination (reverse osmosis (RO) and multistage flash desalination (MSF)) became a viable, economical, and sustainable source of fresh water throughout the world. -

Conceptual Understanding of Osmosis and Diffusion by Australian First-Year Biology Students

International Journal of Innovation in Science and Mathematics Education, 27(9), 17-33, 2019 Conceptual Understanding of Osmosis and Diffusion by Australian First-year Biology Students Nicole B. Reinkea, Mary Kynna and Ann L. Parkinsona Corresponding author: Nicole B. Reinke ([email protected]) aSchool of Health and Sport Sciences, University of the Sunshine Coast, Sippy Downs QLD 4576, Australia Keywords: biology, osmosis, diffusion, conceptual assessment, misconception Abstract Osmosis and diffusion are essential foundation concepts for first-year biology students as they are a key to understanding much of the biology curriculum. However, mastering these concepts can be challenging due to their interdisciplinary and abstract nature. Even at their simplest level, osmosis and diffusion require the learner to imagine processes they cannot see. In addition, many students begin university with flawed beliefs about these two concepts which will impede learning in related areas. The aim of this study was to explore misconceptions around osmosis and diffusion held by first-year cell biology students at an Australian regional university. The 18- item Osmosis and Diffusion Conceptual Assessment was completed by 767 students. From the results, four key misconceptions were identified: approximately half of the participants believed dissolved substances will eventually settle out of a solution; approximately one quarter thought that water will always reach equal levels; one quarter believed that all things expand and contract with temperature; and nearly one third of students believed molecules only move with the addition of external force. Greater attention to identifying and rectifying common misconceptions when teaching first-year students will improve their conceptual understanding of these concepts and benefit their learning in subsequent science subjects. -

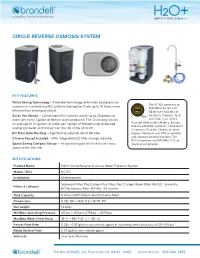

Circle Reverse Osmosis System

CIRCLE REVERSE OSMOSIS SYSTEM KEY FEATURES Water Saving Technology – Patented technology eliminates backpressure The RC100 conforms to common in conventional RO systems making the Circle up to 10 times more NSF/ANSI 42, 53 and efficient than existing products. 58 for the reduction of Saves You Money – Conventional RO systems waste up to 24 gallons of Aesthetic Chlorine, Taste water per every 1 gallon of filtered water produced. The Circle only wastes and Odor, Cyst, VOCs, an average of 2.1 gallons of water per 1 gallon of filtered water produced, Fluoride, Pentavalent Arsenic, Barium, Radium 226/228, Cadmium, Hexavalent saving you water and money over the life of the product!. Chromium, Trivalent Chromium, Lead, RO Filter Auto Flushing – Significantly extends life of RO filter. Copper, Selenium and TDS as verified Chrome Faucet Included – With integrated LED filter change indicator. and substantiated by test data. The RC100 conforms to NSF/ANSI 372 for Space Saving Compact Design – Integrated rapid refill tank means more low lead compliance. space under the sink. SPECIFICATIONS Product Name H2O+ Circle Reverse Osmosis Water Filtration System Model / SKU RC100 Installation Undercounter Sediment Filter, Pre-Carbon Plus Filter, Post Carbon Block Filter (RF-20): 6 months Filters & Lifespan RO Membrane Filter (RF-40): 24 months Tank Capacity 6 Liters (refills fully in less than one hour) Dimensions 9.25” (W) x 16.5” (H) x 13.75” (D) Net weight 14.6 lbs Min/Max Operating Pressure 40 psi – 120 psi (275Kpa – 827Kpa) Min/Max Water Feed Temp 41º F – 95º F (5º C – 35º C) Faucet Flow Rate 0.26 – 0.37 gallons per minute (gpm) at incoming water pressure of 20–100 psi Rated Service Flow 0.07 gallons per minute (gpm) Warranty One Year Warranty PO Box 470085, San Francisco CA, 94147–0085 brondell.com 888-542-3355. -

Characterization and Performance of Nanofiltration Membranes

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Covenant University Repository Environ Chem Lett (2014) 12:241–255 DOI 10.1007/s10311-014-0457-3 REVIEW Characterization and performance of nanofiltration membranes Oluranti Agboola • Jannie Maree • Richard Mbaya Received: 16 October 2013 / Accepted: 17 January 2014 / Published online: 1 February 2014 Ó Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2014 Abstract The availability of clean water has become a nanofiltration membranes. We also present a new concept critical problems facing the society due to pollution by for membrane characterization by quantitative analysis of human activities. Most regions in the world have high phase images to elucidate the macro-molecular packing at demands for clean water. Supplies for freshwater are under the membrane surface. pressure. Water reuse is a potential solution for clean water scarcity. A pressure-driven membrane process such as Keywords Nanofiltration membranes Á Membrane nanofiltration has become the main component of advanced characterizations Á Pore size Á Surface morphology Á water reuse and desalination systems. High rejection and Performance evaluation Á ImageJ software water permeability of solutes are the major characteristics that make nanofiltration membranes economically feasible for water purification. Recent advances include the pre- Introduction diction of membrane performances under different oper- ating conditions. Here, we review the characterization of Nanofiltration process is one of the most important recent nanofiltration membranes by methods such as scanning developments in the process industries. It shows performance electron microscopy, thermal gravimetric analysis, attenu- characteristics, which fall in between that of ultrafiltration ated total reflection Fourier transform infrared spectros- and reverse osmosis membranes (Mohammed and Takriff copy, and atomic force microscopy. -

Crystallization of Oxytetracycline from Fermentation Waste Liquor: Influence of Biopolymer Impurities

Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 279 (2004) 100–108 www.elsevier.com/locate/jcis Crystallization of oxytetracycline from fermentation waste liquor: influence of biopolymer impurities Shi-zhong Li a,1, Xiao-yan Li a,∗, Dianzuo Wang b a Environmental Engineering Research Centre, Department of Civil Engineering, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China b Chinese Academy of Engineering, Beijing 100038, China Received 28 January 2004; accepted 17 June 2004 Available online 29 July 2004 Abstract Organic impurities in the fermentation broth of antibiotic production impose great difficulties in the crystallization and recovery of antibi- otics from the concentrated waste liquor. In the present laboratory study, the inhibitory effect of biopolymers on antibiotic crystallization was investigated using oxytetracycline (OTC) as the model antibiotic. Organic impurities separated from actual OTC fermentation waste liquor by ultrafiltration were dosed into a pure OTC solution at various concentrations. The results demonstrated that small organic molecules with an apparent molecular weight (AMW) of below 10,000 Da did not affect OTC crystallization significantly. However, large biopolymers, especially polysaccharides, in the fermentation waste caused severe retardation of crystal growth and considerable deterioration in the pu- rity of the OTC crystallized. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) revealed that OTC nuclei formed in the solution attached to the surfaces of large organic molecules, probably polysaccharides, instead of being surrounded by proteins as previously thought. It is proposed that the attachment of OTC nuclei to biopolymers would prevent OTC from rapid crystallization, resulting in a high OTC residue in the aqueous phase. In addition, the adsorption of OTC clusters onto biopolymers would destabilize the colloidal system of organic macromolecules and promote particle flocculation. -

Microfiltration of Cutting-Oil Emulsions Enhanced by Electrocoagulation

This article was downloaded by: [Faculty of Chemical Eng & Tech], [Krešimir Košutić] On: 30 April 2015, At: 03:13 Publisher: Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Desalination and Water Treatment Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tdwt20 Microfiltration of cutting-oil emulsions enhanced by electrocoagulation b a a b Janja Križan Milić , Emil Dražević , Krešimir Košutić & Marjana Simonič a Faculty of Chemical Engineering and Technology, Department of Physical Chemistry, University of Zagreb, Marulićev trg 19, HR-10000 Zagreb, Croatia, Tel. +385 1 459 7240 b Faculty of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Laboratory for Water Treatment, University of Maribor, Smetanova 17, SI-2000 Maribor, Slovenia Published online: 30 Apr 2015. Click for updates To cite this article: Janja Križan Milić, Emil Dražević, Krešimir Košutić & Marjana Simonič (2015): Microfiltration of cutting-oil emulsions enhanced by electrocoagulation, Desalination and Water Treatment, DOI: 10.1080/19443994.2015.1042067 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19443994.2015.1042067 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. -

Particle Separation and Fractionation by Microfiltration

Particle separation and fractionation by microfiltration Promotor: Prof. Dr. Ir. R.M. Boom Hoogleraar Levensmiddelenproceskunde, Wageningen Universiteit Copromotoren: Dr. Ir. C.G.P.H. Schro¨en Universitair docent, sectie Proceskunde, Wageningen Universiteit Dr. Ir. R.G.M. van der Sman Universitair docent, sectie Proceskunde, Wageningen Universiteit Promotiecommissie: Prof. Dr. Ir. J.A.M. Kuipers Universiteit Twente Prof. Dr. Ir. M. Wessling Universiteit Twente Dr. Ir. A. van der Padt Royal Friesland Foods Prof. Dr. M.A. Cohen Stuart Wageningen Universiteit Janneke Kromkamp Particle separation and fractionation by microfiltration Scheiding en fractionering van deeltjes middels microfiltratie Proefschrift Ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor op gezag van de rector magnificus van Wageningen Universiteit, Prof.dr. M.J. Kropff, in het openbaar te verdedigen op dinsdag 6 september 2005 des namiddags te vier uur in de Aula. Particle separation and fractionation by microfiltration Janneke Kromkamp Thesis Wageningen University, The Netherlands, 2005 - with Dutch summary ISBN: 90-8504-239-9 Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Membrane filtration 2 1.2 Microfiltration 2 1.3 Mass transport 5 1.4 Shear-induced diffusion 7 1.5 Research aim and outline 9 2 Lattice Boltzmann simulation of 2D and 3D non-Brownian suspensions in Couette flow 13 2.1 Introduction 14 2.2 Computer simulation method 15 2.2.1 Simulation of the fluid 15 2.2.2 Fluid-particle interactions 17 2.2.3 Accuracy of particle representation and particle-particle interactions 18 2.3 Single and pair particles -

Guideline on the Quality of Water for Pharmaceutical Use

20 July 2020 EMA/CHMP/CVMP/QWP/496873/2018 Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) Committee for Medicinal Products for Veterinary Use (CVMP) Guideline on the quality of water for pharmaceutical use Draft agreed by Quality Working Party 7 June 2018 Adopted by CHMP for release for consultation 28 June 2018 Adopted by CVMP for release for consultation 19 July 2018 Start of public consultation 15 November 2018 End of consultation (deadline for comments) 15 May 2019 Agreed by GMDP IWG 5 March 2020 Agreed by BWP 18 March 2020 Agreed by QWP 6 May 2020 Adopted by CHMP for publication 28 May 2020 Adopted by CVMP for publication 18 June 2020 Date for coming into effect 1 February 2021 This guideline replaces the Note for guidance on quality of water for pharmaceutical use (CPMP/QWP/158/01 EMEA/CVMP/115/01) and CPMP Position Statement on the Quality of Water used in the production of Vaccines for parenteral use (EMEA/CPMP/BWP/1571/02 Rev.1). Keywords Guideline, water for injections, purified water, Ph. Eur. Official address Domenico Scarlattilaan 6 ● 1083 HS Amsterdam ● The Netherlands Address for visits and deliveries Refer to www.ema.europa.eu/how-to-find-us An agency of the European Union Send us a question Go to www.ema.europa.eu/contact Telephone +31 (0)88 781 6000 © European Medicines Agency, 2020. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Guideline on the quality of water for pharmaceutical use Table of contents Executive summary ..................................................................................... 3 1. Introduction (background) ...................................................................... 3 2. Scope....................................................................................................... 4 3.