Tremendous Upside Potential: How a High-School Basketball Player Might Challenge the National Basketball Association's Eligibility Requirements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

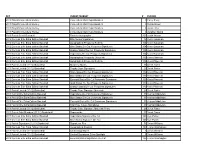

Set Insert/Subset # Player

SET INSERT/SUBSET # PLAYER 2011 Playoff Contenders Hockey Contenders Match-Ups Booklets 8 Corey Perry 2011 Playoff Contenders Hockey Contenders Match-Ups Booklets 8 Dustin Brown 2011 Playoff Contenders Hockey Contenders Match-Ups Booklets 8 Jonas Hiller 2011 Playoff Contenders Hockey Contenders Match-Ups Booklets 8 Jonathan Quick 2013 Panini Select Baseball Rookies Autographs 202 Justin Wilson 2012 Donruss Elite Extra Edition Baseball Elite Series Signatures 12 Kevin Gausman 2012 Donruss Elite Extra Edition Baseball Autographed Prospects Red Ink 104 Kevin Gausman 2012 Donruss Elite Extra Edition Baseball Blue Status Die Cut Prospects Signatures 104 Kevin Gausman 2012 Donruss Elite Extra Edition Baseball Orange Status Die Cut Prospects Signatures 104 Kevin Gausman 2012 Donruss Elite Extra Edition Baseball Aspirations Die Cut Prospects Signatures 104 Kevin Gausman 2012 Donruss Elite Extra Edition Baseball Autographed Prospects Green Ink 119 Kevin Plawecki 2012 Donruss Elite Extra Edition Baseball Autographed Prospects Red Ink 119 Kevin Plawecki 2011 Panini Limited (11-12) Basketball Masterful Marks 18 Derek Fisher 2011 Panini Limited (11-12) Basketball Trophy Case Signatures 29 Derek Fisher 2012 Donruss Elite Extra Edition Baseball Black Status Die Cut Prospect Signatures 119 Kevin Plawecki 2012 Donruss Elite Extra Edition Baseball Blue Status Die Cut Prospects Signatures 119 Kevin Plawecki 2012 Donruss Elite Extra Edition Baseball Emerald Status Die Cut Prospects Signatures 119 Kevin Plawecki 2012 Donruss Elite Extra Edition Baseball Gold -

COWBOY COACHES Head Coach

COWBOY COACHES Head Coach Outlook Coaches Cowboys Opponents STEVE McCLAIN Review Records HEAD BASKETBALL COACH Traditions (Chadron State ‘84) Staff MWC teve McClain enters his First Team All-Mountain West Conference: Josh Davis (1999-2000 ninth season as head and 2000-01); Marcus Bailey (2000-01 and 2001-02); Uche Nsonwu- Scoach at the University of Amadi (2002-03); Donta Richardson (2002-03) and Jay Straight Wyoming. In his eight previous (2004-05). seasons at Wyoming, McClain The high point of the Cowboys’ return to national prominence was has led Wyoming Basketball Wyoming’s appearance in the 2002 NCAA Tournament. It marked the through one of its most school’s fi rst appearance since 1988. Wyoming’s fi rst round win over successful periods in school No. 6 ranked Gonzaga, 73-66, on March 14, 2002, was Wyoming’s fi rst history. When you begin to list NCAA Tournament win since March 14, 1987, when UW defeated No. the accomplishments over the 4 ranked UCLA, 78-68. With their fi rst round win in the 2002 NCAA past eight seasons, one begins Tournament, the Pokes ended the season among the Top 32 teams in to realize how far the Cowboy the country. For his outstanding coaching, McClain was selected the Basketball program has come. 2001-02 MWC Coach of the Year by his fellow coaches. In four of the last eight In the 2000-01 season, he earned Mountain West Conference seasons, Wyoming has appeared in postseason play. The Pokes Coach of the Year honors from CollegeInsider.com, and earned the advanced to the Second Round of the 2002 NCAA Tournament and same honor from MWC media members for the 1999-2000 season. -

Texas Review of & Sports

Texas Review of Entertainment & Sports Law Volume 15 Fall 2013 Number 1 Finding a Solution: Getting Professional Basketball Players Paid Overseas Steven Olenick, Jenna Kochen, and Jason Sosnovsky Analyzing the United States - Japanese Player Contract Agreement: Is this Agreement in the best interest of Major League Baseball players and if not, should the MLB Players Association challenge the legality of Agreement as a violation of federal law? Robert J Romano All Quiet on the Digital Front: The NCAAs Wide Discretion in Regulating Social Media Aaron Hernandez Get with the Times: Why Defamation Law Must be Reformed in Order to Protect Athletes and Celebrities from Media Attacks Matthew T Poorman TRESL Symposium 2013 Panel Discussion: "Asking the Audience for Help: Crowdfunding as a Means of Control" September 13, 2013 - The University of Texas at Austin Published by The University of Texas School of Law Texas Review of Volume 15 Issue 1 Entertainment Fall2013 & Sports Law CONTENTS ARTICLES FINDING A SOLUTION: GETTING PROFESSIONAL BASKETBALL PLAYERS PAID O V ER SEAS ....................................................................................................... 1 Steven Olenick, Jenna Kochen, and Jason Sosnovsky ANALYZING THE UNITED STATES - JAPANESE PLAYER CONTRACT AGREEMENT: IS THIS AGREEMENT IN THE BEST INTEREST OF MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL PLAYERS AND IF NOT, SHOULD THE MLB PLAYERS ASSOCIATION CHALLENGE THE LEGALITY OF THE AGREEMENT AS A VIOLATION OF FEDERAL LAW?..... .. 19 Robert J. Romano NOTES ALL QUIET ON THE DIGITAL FRONT: THE -

Single-File Crabbing in Port Orford

C M C M Y K Y K DEADLY STAMPEDE WAR OF THE ROSES Sixty-one perish after Ivory Coast fireworks show, A7 Pac-12’s Stanford beats Wisconsin, B1 Serving Oregon’s South Coast Since 1878 WEDNESDAY,JANUARY 2, 2013 theworldlink.com I 75¢ Single-file crabbing in Port Orford BY JESSIE HIGGINS get a long stretch of stormy weath- along the channel as the tide reced- pass each other. It really slows the negating the need for dredging. But The World er that fills the port with sand.” ed and run their propellers. The operation down.” that would mean less protection The Port of Port Orford has not hope was, the action would push Anderson and the 40 to 60 fish- from storms. PORT ORFORD — Commercial been dredged since 2009, when enough sand out to sea with the ermen who use the port are looking “We’re looking at all our crabbers around Oregon headed Congress banned federal earmark- tide to deepen the channel for the for a more long-term solution to options,”Anderson said. out to collect their pots Monday, ing. Now, the U.S. Army Corps of crab season. the dredging problem. One possi- The Port of Port Orford is a nat- the first day of this year’s crab sea- Engineers ranks Oregon ports by But the weather was stormy in bility is for the port to seek out ural deep water port. Unlike most son. the amount of goods they export. the days leading up to the season, grant money to purchase its own Oregon ports, it is not connected to But in Port Orford, the fisher- Only the top exporting ports are and the fishermen didn’t want to dredging equipment. -

The Pennsylvania State University Schreyer Honors College

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF LABOR AND EMPLOYMENT RELATIONS PLAYERS IN POWER: A HISTORICAL REVIEW OF CONTRACTUALLY BARGAINED AGREEMENTS IN THE NBA INTO THE MODERN AGE AND THEIR LIMITATIONS ERIC PHYTHYON SPRING 2020 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in Political Science and Labor and Employment Relations with honors in Labor and Employment Relations Reviewed and approved* by the following: Robert Boland J.D, Adjunct Faculty Labor & Employment Relations, Penn State Law Thesis Advisor Jean Marie Philips Professor of Human Resources Management, Labor and Employment Relations Honors Advisor * Electronic approvals are on file. ii ABSTRACT: This paper analyzes the current bargaining situation between the National Basketball Association (NBA), and the National Basketball Players Association (NBPA) and the changes that have occurred in their bargaining relationship over previous contractually bargained agreements, with specific attention paid to historically significant court cases that molded the league to its current form. The ultimate decision maker for the NBA is the Commissioner, Adam Silver, whose job is to represent the interests of the league and more specifically the team owners, while the ultimate decision maker for the players at the bargaining table is the National Basketball Players Association (NBPA), currently led by Michele Roberts. In the current system of negotiations, the NBA and the NBPA meet to negotiate and make changes to their collective bargaining agreement as it comes close to expiration. This paper will examine the 1976 ABA- NBA merger, and the resulting impact that the joining of these two leagues has had. This paper will utilize language from the current collective bargaining agreement, as well as language from previous iterations agreed upon by both the NBA and NBPA, as well information from other professional sports leagues agreements and accounts from relevant parties involved. -

“A Functional Well-Appointed Locker Room

A FUNCTIONAL, WELL APPOINTED LOCKER ROOM In a huge sports complex like the Target Center, located in downtown Min- neapolis, Minnesota, the locker room may be considered almost an after- thought. Yet in order to attract and keep a National Basketball Association team and to provide a highly visible location for pre- and post-game televi- sion interviews, the locker room becomes much more important. The Target Center is a city owned sports and entertainment facility constructed in 1989 as a requirement to receive a National Basketball Association team. The NBA Minnesota Timberwolves remain a primary user of the facility. To replace the plain laminate locker room, the Minneapolis Community Devel- opment Agency (MCDA) went to architect Setter, Leach & Lindstrom of Min- neapolis. The architects decided to design a facility that would be a functional locker room yet give the apearance of a well appointed boardroom. Their Photos by H. Larson Photography goal was to provide a quality locker room environment for an NBA team, and the room had to be a presentable space for functions such as televised player A view of the locker room showing the interviews. They selected cherry for the lockers, cabinetry, paneling and trim hardware installed inside the lockers. Like the cherry woodwork, the hardware because of its color and quality appearance. AWI member Siewert Cabinet was selected for durability in a high wear & Fixture Mfg., Inc. of Minneapolis provided the high quality woodwork area as well as appearance. Selecting and throughout the room. installing the hardware presented a challenge to the woodworker The locker room is a hard use area, so the lockers had to be durable and carefully designed to wear well. -

Fastest 40 Minutes in Basketball, 2012-2013

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Arkansas Men’s Basketball Athletics 2013 Media Guide: Fastest 40 Minutes in Basketball, 2012-2013 University of Arkansas, Fayetteville. Athletics Media Relations Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/basketball-men Citation University of Arkansas, Fayetteville. Athletics Media Relations. (2013). Media Guide: Fastest 40 Minutes in Basketball, 2012-2013. Arkansas Men’s Basketball. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.uark.edu/ basketball-men/10 This Periodical is brought to you for free and open access by the Athletics at ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arkansas Men’s Basketball by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TABLE OF CONTENTS This is Arkansas Basketball 2012-13 Razorbacks Razorback Records Quick Facts ........................................3 Kikko Haydar .............................48-50 1,000-Point Scorers ................124-127 Television Roster ...............................4 Rashad Madden ..........................51-53 Scoring Average Records ............... 128 Roster ................................................5 Hunter Mickelson ......................54-56 Points Records ...............................129 Bud Walton Arena ..........................6-7 Marshawn Powell .......................57-59 30-Point Games ............................. 130 Razorback Nation ...........................8-9 Rickey Scott ................................60-62 -

2018-19 Phoenix Suns Media Guide 2018-19 Suns Schedule

2018-19 PHOENIX SUNS MEDIA GUIDE 2018-19 SUNS SCHEDULE OCTOBER 2018 JANUARY 2019 SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT 1 SAC 2 3 NZB 4 5 POR 6 1 2 PHI 3 4 LAC 5 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM PRESEASON PRESEASON PRESEASON 7 8 GSW 9 10 POR 11 12 13 6 CHA 7 8 SAC 9 DAL 10 11 12 DEN 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 6:00 PM 7:00 PM 6:30 PM 7:00 PM PRESEASON PRESEASON 14 15 16 17 DAL 18 19 20 DEN 13 14 15 IND 16 17 TOR 18 19 CHA 7:30 PM 6:00 PM 5:00 PM 5:30 PM 3:00 PM ESPN 21 22 GSW 23 24 LAL 25 26 27 MEM 20 MIN 21 22 MIN 23 24 POR 25 DEN 26 7:30 PM 7:00 PM 5:00 PM 5:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 28 OKC 29 30 31 SAS 27 LAL 28 29 SAS 30 31 4:00 PM 7:30 PM 7:00 PM 5:00 PM 7:30 PM 6:30 PM ESPN FSAZ 3:00 PM 7:30 PM FSAZ FSAZ NOVEMBER 2018 FEBRUARY 2019 SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT 1 2 TOR 3 1 2 ATL 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 4 MEM 5 6 BKN 7 8 BOS 9 10 NOP 3 4 HOU 5 6 UTA 7 8 GSW 9 6:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 5:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 11 12 OKC 13 14 SAS 15 16 17 OKC 10 SAC 11 12 13 LAC 14 15 16 6:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 4:00 PM 8:30 PM 18 19 PHI 20 21 CHI 22 23 MIL 24 17 18 19 20 21 CLE 22 23 ATL 5:00 PM 6:00 PM 6:30 PM 5:00 PM 5:00 PM 25 DET 26 27 IND 28 LAC 29 30 ORL 24 25 MIA 26 27 28 2:00 PM 7:00 PM 8:30 PM 7:00 PM 5:30 PM DECEMBER 2018 MARCH 2019 SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT 1 1 2 NOP LAL 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 2 LAL 3 4 SAC 5 6 POR 7 MIA 8 3 4 MIL 5 6 NYK 7 8 9 POR 1:30 PM 7:00 PM 8:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 8:00 PM 9 10 LAC 11 SAS 12 13 DAL 14 15 MIN 10 GSW 11 12 13 UTA 14 15 HOU 16 NOP 7:00 -

Fullerton Interested in OSU Presidency

Spartans' Fleming turns big loss into gain, page 6 af)Aff2 11( Volume 82, No. 21 Serving the San Jose State University Corn m unity Since 1934 Wednesday, February 29, 1984 Fullerton interested in OSU presidency By Mark Katches Santa Cruz home was rine negative SJSU President Gail Fullerton factor. said she is interested in the Oregon SJSU President one of six candidates sought On the positive side, Fullerton State University presidency, but said she is involved with several choosing to leave SJSU would be a programs at SJSU that she would difficult decision. Education in mid-March. Fullerton and said she was im- taking part in the selection process. their interviews. The final candi- like to see completed. "I'm thinking about it," she said Fullerton travelled to Oregon pressed. Fullerton did not pursue the dates will meet with students and Redeveloping facilities for the of the chance to head north. "But last week and was the first candi- "She is a very competent ad- OSU post but was nominated for it. faculty on the Corvalis campus by School of Engineering, refining cur- haven't packed my bags yet either." date interviewed. In her two-day ministrator. She has proven that at "They sought me," she said. "I next Monday. riculum, and funding the Beethoven Fullerton is one of six candi- stay on campus, she met with stu- San Jose," Wolfard said. "She could haven't been offering my resume Fullerton said she spent several Center are a few things Fullerton dates being considered to replace dent and faculty leaders and also be beneficial here." around or anything." rewarding years in Oregon receiv- said she would like to follow up on as the retiring Robert McVicar at OSU. -

Nº 921 ACB Noticias Digital

Nº 921 AÑO XXVI - 9 Febrero 2015 Departamento de Comunicación TEMPORADA I N D I C E 2014-2015 Jugador de la Jornada 2 Resultados y Clasificaciones 3 JORNADA Topes de la Liga y Dobles Figuras 4 Cuadro de resultados 5 Máximos anotadores 5 20 Clasificaciones Individuales 6-7 Series 8 Clasificaciones de Equipo 8-9 Fichas Partidos Jornada 20 10-14 Estadísticas Acumuladas 15-23 Precedentes y Próximas Jornadas 24 Patrocinador principal ACB 1 Jugador de la Jornada Dani DÍEZ (Gipuzkoa Basket) ACB RANKING Dani Díez ha protagonizado la actuación más destacada de la 20ª jornada al conseguir 32 puntos (3/6 en tiros de dos, 6/7 en tiros de tres y 8/8 en tiros libres), capturar 7 rebotes, 7RWDO 3DU 0HGLD recuperar 1 balón y provocar 5 faltas personales, para una valoración total de 36 puntos Para 3$1.2Ã$1'< el jugador madrileño, ésta es su primera nominación como Jugador de la Jornada 72'2529,&Ã0 Daniel Díez de la Faya es un alero de 2,01 metros, nacido el 07/04/93 en Madrid Formado en 6,.0$Ã/8.( las categorías inferiores del Estudiantes, llegó al equipo júnior del Real Madrid en la temporada -(/29$&Ã67(9$1 2009-10, disputando un partido en LEB Plata y 13 en Liga EBA en la siguiente campaña En la /,0$Ã$8*8672 temporada 2011-12, ya integrado en el equipo EBA, se produce su debut en la Liga Endesa, en 'Ë(=Ã'$1,(/ la que llega a jugar tres partidos La 2012-13 la disputa con el Gipuzkoa Basket, a donde llega en calidad de cedido, regresando al Real Madrid en la temporadas 2013-14 El pasado verano 5,%$6Ã3$8 recala de nuevo en el -

Congressional Record—Senate S5971

June 23, 2008 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE S5971 Mr. REID. I ask unanimous consent there is little public awareness of the impor- The resolution (S. Res. 596) was the bill be read three times, passed, the tance of soil protection; agreed to. motion to reconsider be laid on the Whereas the degradation of soil can be The preamble was agreed to. table with no intervening action or de- rapid, while the formation and regeneration The resolution, with its preamble, processes can be very slow; reads as follows: bate, and any statements relating to Whereas protection of United States soil S. RES. 596 this matter be printed in the RECORD. based on the principles of preservation and The PRESIDING OFFICER. Without enhancement of soil functions, prevention of Whereas, on June 17, 2008, the Boston Celt- objection, it is so ordered. soil degradation, mitigation of detrimental ics won the 2008 National Basketball Asso- The bill (S. 3180) was ordered to be use, and restoration of degraded soils is es- ciation Championship (referred to in this engrossed for a third reading, was read sential to the long-term prosperity of the preamble as the ‘‘2008 Championship’’) in 6 games over the Los Angeles Lakers; the third time, and passed, as follows: United States; Whereas legislation in the areas of organic, Whereas the 2008 Championship was the S. 3180 industrial, chemical, biological, and medical 17th world championship won by the Celtics, Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Rep- waste pollution prevention and control the most in the history of the National Bas- resentatives of the United States of America in should consider soil protection provisions; ketball Association (referred to in this pre- Congress assembled, Whereas legislation on climate change, amble as the ‘‘NBA’’); SECTION 1. -

Single-Season Records

SINGLE-SEASON RECORDS POINTS SCORED FIELD GOALS MADE THREE-POINTERS MADE 1 . 866 Jack Foley, 1961-1962 1 . 322 Jack Foley, 1961-1962 1 . 82 Kevin Hamilton, 2004-2005 2 . 785 Rob Feaster, 1993-1994 2 . 282 Jack Foley, 1960-1961 2 . 81 Dwight Pernell, 1989-1990 3 . 740 Tom Heinsohn, 1955-1956 3 . 261 Rob Feaster, 1993-1994 3 . 65 Gordon Hamilton, 1994-1995 4 . 728 Jack Foley, 1960-1961 261 Ronnie Perry, 1978-1979 65 Jim Nairus, 1990-1991 5 . 700 Ronnie Perry, 1978-1979 5 . 255 Togo Palazzi, 1953-1954 5 . 64 Devin Brown, 2009-2010 6 . 674 Rob Feaster, 1994-1995 6 . 254 Tom Heinsohn, 1955-1956 6 . 63 Kevin Hamilton, 2005-2006 7 . 670 Togo Palazzi, 1953-1954 7 . 250 Ronnie Perry, 1979-1980 7 . 61 Andrew Beinert, 2009-2010 8 . 665 Ronnie Perry, 1979-1980 8 . 232 Tom Heinsohn, 1954-1955 8 . 60 Keith Simmons, 2005-2006 9 . 650 Dwight Pernell, 1989-1990 9 . 229 Jack Foley, 1959-1960 60 Devin Brown, 2010-2011 10. 607 Jim McCaffrey, 1984-1985 10 . 228 Ed Siudut, 1968-1969 10 . 58 Robert Champion, 2015-2016 SCORING AVERAGE FIELD GOALS ATTEMPTED THREE-POINTERS ATTEMPTED 1 . 33 .3 Jack Foley, 1961-1962 1 . 659 Bob Cousy, 1949-1950 1 . 231 Kevin Hamilton, 2004-2005 2 . 28 .0 Rob Feaster, 1993-1994 2 . 639 Jack Foley, 1961-1962 2 . 190 Kevin Hamilton, 2005-2006 3 . 27 .4 Tom Heinsohn, 1955-1956 3 . 630 Tom Heinsohn, 1955-1956 3 . 176 Robert Champion, 2016-2017 4 . 27 .0 Jack Foley, 1960-1961 4 .