Government Report Title 2018 Rural Homelessness Estimation Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021 Court Calendar

Court Calendar and Indigenous Court Worker and Resolution Services Programs 2021 Court Calendar 2021 Court Calendar and Indigenous Court Worker and Resolution Services Programs The 2021 publication is available online at https://albertacourts.ca and www.qp.alberta.ca/1140.cfm. Additional copies of this publication can be ordered from Alberta Queen’s Printer at www.qp.alberta.ca/1140.cfm. Suite 700, Park Plaza Building 10611 - 98 Avenue Edmonton, AB T5K 2P7 Phone: 780-427-4952 Fax: 780-452-0668 Email: [email protected] 1 November, 2020 Court Calendar 2021 COURT CALENDAR JANUARY FEBRUARY MARCH S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 4 5 6 7 8 8 9 10 11 12 8 9 10 11 12 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 15 16 17 18 19 18 19 20 21 22 22 23 24 25 26 22 23 24 25 26 25 26 27 28 29 29 30 31 APRIL MAY JUNE S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S 1 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 4 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 25 26 27 28 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 28 29 30 JULY AUGUST SEPTEMBER S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 5 6 7 8 9 9 10 11 12 13 7 8 9 10 12 13 14 15 16 16 17 18 19 20 13 14 15 16 17 19 20 21 22 23 23 24 25 26 27 20 21 22 23 24 26 27 28 29 30 30 31 27 28 29 30 OCTOBER NOVEMBER DECEMBER S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S 1 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 8 9 10 12 6 7 8 9 10 12 13 14 15 15 16 17 18 19 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 22 23 24 25 26 20 21 22 23 25 26 27 28 29 29 30 2 November, 2020 Court Calendar 2022 COURT CALENDAR JANUARY FEBRUARY MARCH -

Tourist Guide

TOURIST GUIDE 55 AVENUE WWW.52 AVENUEWETASKIWIN.CA Discover Wetaskiwin Wetaskiwin is a City with a growing population of 12,621 and over 700 businesses; the City offers all urban amenities with the charm of a small town. Whether you know us as a city where “Cars cost less” or home to the Reynolds-Alberta Museum, one thing is for sure, Wetaskiwin welcomes you to an adventure. Take in the Rawhide Rodeo or dance to the music at the Loonstock Music Festival. Visit the Wetaskiwin and District Heritage Museum, the Reynolds- Alberta Museum and Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame. Enjoy a show at the Manluk Performing Arts Theatre. Feeling adventurous? Take a rare flight in the open cockpit of a Biplane. Looking for family fun? Surf the Board Rider at the Manluk Aquatic Centre. The Edmonton International Raceway, located in Wetaskiwin, hosts the NASCAR 300 lap race. Whatever your pleasure - there is an experience for everyone in one of Alberta’s oldest cities. Visit our website for local events happening in the community, www.wetaskiwin.ca. MUSEUMS 4 Reynolds-Alberta Museum 6 Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame 8 Wetaskiwin & District Heritage Museum 10 Alberta Central Railway Museum 12 Historic City Hall Tours 14 Wetaskiwin Archives 14 HISTORICAL POINTS OF INTEREST 16 LEISURE & ATTRACTIONS 22 MAP OF WETASKIWIN 28 ACCOMODATIONS 38 RESTAURANTS 42 EXCITING EXCURSIONS 46 VISITORS INFORMATION 48 INDEX 3 MUSEUMS 50 STREET 50 Wetaskiwin is proud to boast of our museums such as the international award-winning Reynolds-Alberta Museum, Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame, the Wetaskiwin and District Heritage Museum, and the Alberta Central Railway Museum. -

Document Master Order #2 Relating to Court's Response to the Covid-19 Virus

COURT COURT OF QUEEN'S BENCH OF ALBERTA CENTRE JUDICIAL CENTRE OF EDMONTON DOCUMENT MASTER ORDER #2 RELATING TO COURT’S RESPONSE TO THE COVID-19 VIRUS ADDRESS FOR SERVICE Clerk of the Court of Queen's Bench of Alberta AND CONTACT Judicial District of Edmonton INFORMATION OF THE Law Courts Building, IA Sir Winston Churchill Square PARTY FILING THIS Edmonton, Alberta T5J OR2 DOCUMENT DATE ON WHICH ORDER WAS PRONOUNCED: March 20, 2020 LOCATION WHERE ORDER WAS PRONOUNCED: Edmonton Alberta NAME OF JUSTICE WHO MADE THIS ORDER: Chief Justice M.T. Moreau UPON the COURT'S own motion; AND UPON it appearing that the WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION (WHO) has declared COVID-19 (also known as the “novel coronavirus) a public health emergency as an international pandemic; AND UPON the Government of Alberta having declared a state of Public Health Emergency on March 17, 2020; AND UPON it appearing that agencies of the Governments of Canada (CANADA) and Alberta (ALBERTA) have issued public health recommendations and directives, under their legislation and powers, in response to COVID-19, including restricted travel and periods of self-isolation in certain circumstances; AND UPON the COURT determining that, in these exceptional circumstances, it must continue to alter its operations, policies and procedures in exercising its statutory, regulatory or inherent jurisdiction in face of and during the emergency arising from this international pandemic of COVID-19, with a view to helping to contain or prevent the spread of COVID-19 and minimizing the risk of and taking -

Cemetery Name Blue Sign Address Legal Contact Name Phone # Mailing Address City/Province Postal Code

Blue Sign Cemetery Name Legal Contact Name Phone # Mailing Address City/Province Postal Code Address Alder Flats Cemetery 74032 Twp Rd 460 SE 5 46 7 W5 Dwight Kellgren 780-621-3451 Box 86 Alder Flats, AB T0C 0A0 Bonnie Glen Cemetery 473063 Rge Rd 275 NW 20 47 27 W4 Julie Schmidt 780-389-2164 Site 2, Box 8, R.R. #2 Thorsby, AB T0C 2P0 Bunker Hill Cemetery Club 463033 Rge Rd 33 SW 22 46 03 W5 Doug Clark 780-910-5272 28 Westwood Crescent Sylvan Lake, AB T4S 1P6 Calvary Baptist Church Cemetery SE 25 46 25 W4 & Wilma Parsons 780-387-2215 4910 Northmount Drive Wetaskiwin, AB T9A 3R2 463041 Rge Rd 252 SW 23 46 25 W4 Crooked Lake Cemetery 471048 Hwy 822 NE 12 47 23 W4 Marilyn Dumkee 780-918-1567 11410 118a Street Edmonton, AB T5G 3J2 Kelly Burkhardt (Plots) 780-352-9533 Dalby Cemetery 461080 Rge Rd 274 NE 8 46 27 W4 JeanAnne Sjolin 780-352-4362 R.R. #1 Wetaskiwin, AB T9A 1W8 Emmaus Lutheran Cemetery 255063 Rge Rd 252 NW 19 46 25 W4 Larry Freiman 780-352-9942 Box 6071 Wetaskiwin, AB T9A 2E8 Grandview Cemetery 261082 Twp Rd 472 SW 14 47 26 W4 Margaret Johnston 780-368-2532 139 4710 Northmount Dr. Wetaskiwin, AB T9A 3P6 Hegge Community Cemetery 461040 Rge Rd 12 SE 10 46 01 W5 Janet Stone 780-586-2363 R.R. #2 Westerose, AB T0C 2V0 Immanuel Lutheran Church Cemetery 453005 Rge Rd 265 SW 20 45 26 W4 Steven Schmidt 780-360-3414 R.R. -

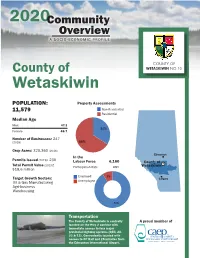

CAEP 2020 Community Overview

2020Community Overview A SOCIO-ECONOMIC PROFILE COUNTY OF County of WETASKIWIN NO.10 Wetaskiwin POPULATION: Property Assessments 11,579 Non-Residential Residential Median Age Male 47.3 34% Female 46.7 Number of Businesses: 247 (2018) 66% Crop Acres: 320,360 (2016) Edmonton In the Permits Issued (2019): 230 Labour Force 6,160 County of Total Permit Value (2019): Participation Rate 68% Wetaskiwin $18.6 million Employed 9% Target Growth Sectors: Calgary Oil & Gas Manufacturing Unemployed Agri-business Warehousing 91% Transportation The County of Wetaskiwin is centrally A proud member of located on the Hwy 2 corridor with immediate access to four major provincial highway systems (QEII, 2A, 22 & 13). Conveniently located with access to CP Rail and 25 minutes from the Edmonton International Airport. Total Households Average Household Income for Tenure $108,992 4,375 Average After-Tax Household Income Average Household Owned 87% $88,019 Consumption Rented 13% 2015 Shelter $20,404 Food $9,181 Household operation & furnishings $7,891 Occupied Private Dwellings by Period Health care $2,949 Transportation $15,690 Occupied Private Dwellingof Construction by Period of Construction Recreation & Entertainment $5,785 2500 Personal care & clothing $5,792 2000 Child Care $435 2040 Education & books $1,337 1500 Miscellaneous expenditures $2,693 Total $72,157 1000 1305 1030 500 Housing by Structure Single Family 3,830 0 Multi-Family 75 Pre 1980 1981-2000 2001-2016 Apartments 10 Movable Dwellings 450 Number of Households by Income Group 1600 1400 1200 1000 800 600 Quality of Life 400 200 The County of Wetaskiwin offers a high quality of life with many recre- 0 ational and community opportunities. -

Newcomers Guide Prepared by City of Wetaskiwin Family & Community Support Services Phone: 780-361-4425 Website: Email: [email protected]

WetWel comkias e towi n NEWCOMERS Photo by Ron Asp GUIDE Welcome to Wetaskiwin ! Whether you have travelled across the globe, across Canada or across Alberta, we are happy that you have chosen Wetaskiwin as your new home. We have developed this Newcomer’s Guide to provide you with valuable information about Wetaskiwin to help ease your transition into your new community. It gives a summary of information and directs you to where you can get more information about how to live, work and play in Wetaskiwin. Wetaskiwin is one of Alberta’s oldest cities. Founded in 1892, the first school was built in 1894 and the first newspaper was established in 1897. Wetaskiwin grew quickly, becoming a town in 1902 and a city in 1906. Today, Wetaskiwin is a thriving city with a population of over 12,500, with lots to offer and many options for services throughout the community. Once you are settled in, we encourage you to ask friends, co-workers or other family members about their favourites. We think you will find Wetaskiwin to be a friendly place to live, work and raise a family. A few facts about Wetaskiwin: • A growing community combining the amenities of a large centre with the relaxing atmosphere of a small town. Wetaskiwin offers beautiful parks, historical sites, fine dining, shopping, cultural programs, and activities. • With four seasons, Wetaskiwin offers its own unique experiences and opportunities. July and August are the warmest months with a temperature range of 15 - 23C. In the winter, November to March, the average temperature is -16 C. -

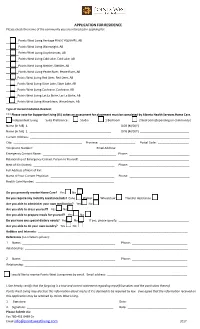

APPLICATION for RESIDENCE Email [email protected]

APPLICATION FOR RESIDENCE Please check the name of the community you are interested in applying for: Points West Living Heritage House Vegreville, AB Points West Living Wainwright, AB Points West Living Lloydminster, AB Points West Living Cold Lake, Cold Lake, AB _______ Points West Living Stettler, Stettler, AB ______ _Points West Living Peace River, Peace River, AB _______Points West Living Red Deer, Red Deer, AB _______Points West Living Slave Lake, Slave Lake, AB _______Points West Living Cochrane, Cochrane, AB _______Points West Living Lac La Biche, Lac La Biche, AB _______Points West Living Wetaskiwin, Wetaskiwin, AB Type of Accommodation Desired: *** Please note for Supportive Living (SL) suites an assessment for placement must be completed by Alberta Health Services Home Care. Independent Living Suite Preference : Studio 1 Bedroom 2 Bedroom (depending on community) Name (in full) 1. __________________________________________________ DOB (M/D/Y) ______________________________ Name (in full) 2. __________________________________________________ DOB (M/D/Y) ______________________________ Current Address: __________________________________________________________________________________________________ City: __________________________________________ Province: ______________________ Postal Code: ___________________ Telephone Number: ____________________________________ Email Address: ____________________________________________ Emergency Contact Name: _____________________________________________ Phone: _____________________________________ -

Court File Number 1901-06027 Court of Queen's Bench Of

COURT FILE NUMBER 1901-06027 COURT OF QUEEN’S BENCH OF ALBERTA JUDICIAL CENTRE CALGARY PLAINTIFF ATB FINANCIAL DEFENDANT SOLO LIQUOR STORES LTD., SOLO LIQUOR HOLDINGS LTD., GENCO HOLDINGS LTD., PALI BEDI, JASBIR SINGH HANS, AND TARLOK SINGH TATLA AND IN THE MATTER OF THE RECEIVERSHIP OF SOLO LIQUOR STORES LTD. and SOLO LIQUOR HOLDINGS LTD. APPLICANT FTI CONSULTING CANADA INC. in its capacity as Court-appointed Receiver and Manager of the assets, undertakings and properties of SOLO LIQUOR STORES LTD. and SOLO LIQUOR HOLDINGS LTD. SERVICE LIST Party Telephone Fax Role TORYS LLP 403-776-3744 403-776-3800 Counsel to 525 – 8th Avenue S.W., Receiver 46th Floor Eighth Avenue Place East Calgary, AB T2P 1G1 KYLE KASHUBA Email: [email protected] FTI CONSULTING 403-232-6116 Receiver 520 5th Ave SW Suite 1610 Calgary AB T2P 3R7 DERYCK HELKAA Email: [email protected] 403-454-6041 DUSTIN OLVER Email: [email protected] 403-454-6032 LINDSAY SHIERMAN Email: [email protected] 403-454-6036 27833633.4 Party Telephone Fax Role BLAKE, CASSELS & GRAYDON LLP 403-260-9700 Counsel to ATB 3500, 855 – 2nd Street SW Financial Calgary, AB T2P 4J8 RYAN ZAHARA E-mail: [email protected] 403-260-9628 MATTHEW SUMMERS Email: [email protected] 403-260-9677 ATB FINANCIAL Secured Creditor 3rd Floor, 217 - 16 Avenue NW Calgary, AB T2M 0H5 TRINA HOLLAND Email: [email protected] CROWN CAPITAL PARTNERS INC. Secured Creditor 2730, 333 Bay Street Toronto, ON M5H 2R2 CHRIS JOHNSON Email: [email protected] 416-640-6715 TIM OLDFIELD Email: [email protected] 416-640-6798 McCARTHY TÉTRAULT 403-260-3500 403-260-3501 Counsel to Solo 421 7th Avenue SW Liquor / Solo Suite 4000 Holdings Calgary AB T2P 4K9 WALKER MACLEOD Email: [email protected] 403-260-3710 SEAN COLLINS Email: [email protected] 403-260-3531 MLT AIKINS 306-975-7100 306-975-7145 Counsel to Crown 1500 Saskatoon Square Capital 410 – 22nd Street East Saskatoon, SK S7K 5T6 JEFF LEE, Q.C. -

These Qualified Assessment Review Board Members Have Agreed to Have Their Names Published, and May Be Available to Sit As Board Members in Another Municipality

Assessment Review Board Members These qualified Assessment Review Board Members have agreed to have their names published, and may be available to sit as board members in another municipality. If you require an Assessment Review Board Member for your municipality, please contact the Assessment Review Board Clerk or the CAO of a muncipality near you for further information. Assessment Review Board Members Municipality Phone number First Name Last Name Athabasca County 780-675-2273 Brian Bahry Athabasca County 780-675-2273 Jack Dowhaluk Athabasca County 780-675-2273 Ron Epp Athabasca County 780-675-2273 Kevin Haines Athabasca County 780-675-2273 Emil Zachkewich Beaver County 780-663-3730 Blair Ewasiuk Beaver County 780-663-3730 Jennifer Goertzen Beaver County 780-663-3730 Evie Kuz Beaver County 780-663-3730 Phyllis Lefsrud Beaver County 780-663-3730 Peter McArthur Beaver County 780-663-3730 James Young Brazeau County 780-542-7777 Bob Kitching Brazeau County 780-542-7777 Bill Urchyshyn Camrose County 780-672-4446 Don Gregorwich Camrose County 780-672-4446 Doug Lyseng Cardston County 403-653-4977 Randy Janisko Cardston County 403-653-4977 Delton Jensen City of Airdrie 403-948-8800 Linda Eckhart City of Airdrie 403-948-8800 Catherine Greene City of Airdrie 403-948-8800 Dan Oneil City of Airdrie 403-948-8800 Janis Risi City of Airdrie 403-948-8800 Christa Sanders City of Brooks 403-362-3333 Bevin Keith City of Brooks 403-362-3333 Noel Moriyama City of Brooks 403-362-3333 Susan Robertson City of Calgary 403-268-2489 Kevin Barry Bickford City of Calgary 403-268-2489 Arlene Blake Page 1 of 15 This list is subject to change without notice. -

Camrose to Edmonton Edmonton to Camrose

Augustana Campus Library www.library.ualberta.ca/augustana/ 4901 46 Avenue ph: 780-679-1156 Camrose, Alberta T4V 2R3 fax: 780-679-1594 Edmonton to Camrose • From Hwy. 216 (Anthony Henday Dr.), exit onto Hwy. 14 Eastbound toward Wainwright for 37 km • Follow Hwy. 14 for 7.9 km (7 minutes), then take the exit for Camrose, Hwy. 21 (South) • Stay on Hwy. 21 Southbound for 60.5 km (37 minutes) until you come to the intersection Hwy. 21 with Hwy. 13 • Turn Left onto Hwy. 13 (East) to Camrose city limits (4 km) • As you enter Camrose, Hwy. 13 becomes 48 Avenue • Continue East on 48 Avenue until you reach the intersection of 50 Street. Turn Right onto 50 Street (South) • Turn Left at 46 Avenue (East) • Take your first Right (South). Drive into Augustana Campus. Visitor parking is to your left. The library is located to the left of Founder’s Hall. Camrose to Edmonton • From Augustana campus turn Left (West) on 46 Ave • Take your first Right onto 50 Street (North) • Take your second Left onto 48 Ave (West) • Proceed West on 48 Avenue. As you leave the city, it becomes Hwy. 13. Follow Hwy. 13 for 4 km • At the intersection of Hwy 13 & 21, turn Right on Hwy. 21 (North) • Continue North on Hwy. 21 for 60 km (37 minutes) • Exit onto Hwy. 14 (West) travelling 7.9 km (7 minutes) • Merge onto Anthony Henday Drive (Hwy. 216) Augustana Campus Library www.library.ualberta.ca/augustana/ 4901 46 Avenue ph: 780-679-1156 Camrose, Alberta T4V 2R3 fax: 780-679-1594 Edmonton to Camrose • From Hwy. -

Legend - AUPE Area Councils Whiskey Gap Del Bonita Coutts

Indian Cabins Steen River Peace Point Meander River 35 Carlson Landing Sweet Grass Landing Habay Fort Chipewyan 58 Quatre Fourches High Level Rocky Lane Rainbow Lake Fox Lake Embarras Portage #1 North Vermilion Settlemen Little Red River Jackfish Fort Vermilion Vermilion Chutes Fitzgerald Embarras Paddle Prairie Hay Camp Carcajou Bitumount 35 Garden Creek Little Fishery Fort Mackay Fifth Meridian Hotchkiss Mildred Lake Notikewin Chipewyan Lake Manning North Star Chipewyan Lake Deadwood Fort McMurray Peerless Lake #16 Clear Prairie Dixonville Loon Lake Red Earth Creek Trout Lake #2 Anzac Royce Hines Creek Peace River Cherry Point Grimshaw Gage 2 58 Brownvale Harmon Valley Highland Park 49 Reno Blueberry Mountain Springburn Atikameg Wabasca-desmarais Bonanza Fairview Jean Cote Gordondale Gift Lake Bay Tree #3 Tangent Rycroft Wanham Eaglesham Girouxville Spirit River Mclennan Prestville Watino Donnelly Silverwood Conklin Kathleen Woking Guy Kenzie Demmitt Valhalla Centre Webster 2A Triangle High Prairie #4 63 Canyon Creek 2 La Glace Sexsmith Enilda Joussard Lymburn Hythe 2 Faust Albright Clairmont 49 Slave Lake #7 Calling Lake Beaverlodge 43 Saulteaux Spurfield Wandering River Bezanson Debolt Wembley Crooked Creek Sunset House 2 Smith Breynat Hondo Amesbury Elmworth Grande Calais Ranch 33 Prairie Valleyview #5 Chisholm 2 #10 #11 Grassland Plamondon 43 Athabasca Atmore 55 #6 Little Smoky Lac La Biche Swan Hills Flatbush Hylo #12 Colinton Boyle Fawcett Meanook Cold Rich Lake Regional Ofces Jarvie Perryvale 33 2 36 Lake Fox Creek 32 Grand Centre Rochester 63 Fort Assiniboine Dapp Peace River Two Creeks Tawatinaw St. Lina Ardmore #9 Pibroch Nestow Abee Mallaig Glendon Windfall Tiger Lily Thorhild Whitecourt #8 Clyde Spedden Grande Prairie Westlock Waskatenau Bellis Vilna Bonnyville #13 Barrhead Ashmont St. -

Wetaskiwin & Area

Alberta Health Primary Care Network (PCN) Profiles Wetaskiwin & Area PCN Version 1, September 2015 Alberta Health, Primary Health Care September 2015 Primary Care Network: Wetaskiwin & Area PCN Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. i Primary Care Network (PCN) Information ...................................................................................... 1 Provincial Map of GP Services for the Primary Care Network ............................................................... 2 Local Focused Map of Select GP Services for the Primary Care Network .......................................... 3 Demographics ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Table 1.1 Distribution of PCN Panel Population by Age and Gender as at March 31, 2014 ................. 4 Figure 1.1 Percentage Distribution of the PCN Panel versus All Alberta PCNs Population by Age Groups as at March 31, 2014 ...................................... 4 Figure 1.2 Primary Care Network Panel Population as at End of Fiscal Years 2010 – 2014 ................. 5 Socio-Economic Indicators ....................................................................................................................... 6 Table 2.1 Population Percentage of First Nations with Treaty Status and Inuit as at March 31, 2014 .. 6 Chronic Disease Prevalence .....................................................................................................................