Introduction to Felipe Ehrenberg's “In Search of A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Materials & Process

Sculpture: Materials & Process Teaching Resource Developed by Molly Kysar 2001 Flora Street Dallas, TX 75201 Tel 214.242.5100 Fax 214.242.5155 NasherSculptureCenter.org INDEX INTRODUCTION 3 WORKS OF ART 4 BRONZE Material & Process 5-8 Auguste Rodin, Eve, 1881 9-10 George Segal, Rush Hour, 1983 11-13 PLASTER Material & Process 14-16 Henri Matisse, Madeleine I, 1901 17-18 Pablo Picasso, Head of a Woman (Fernande), 1909 19-20 STEEL Material & Process 21-22 Antony Gormley, Quantum Cloud XX (tornado), 2000 23-24 Mark di Suvero, Eviva Amore, 2001 24-25 GLOSSARY 26 RESOURCES 27 ALL IMAGES OF WORKS OF ART ARE PROTECTED UNDER COPYRIGHT. ANY USES OTHER THAN FOR EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES ARE STRICTLY FORBIDDEN. 2 Introduction This resource is designed to introduce students in 4th-12th grades to the materials and processes used in modern and traditional sculpture, specifically bronze, plaster, and steel. The featured sculptures, drawn from the collection of the Nasher Sculpture Center, range from 1881 to 2001 and represent only some of the many materials and processes used by artists whose works of art are in the collection. Images from this packet are also available in a PowerPoint presentation for use in the classroom, available at nashersculpturecenter.org. DISCUSS WITH YOUR STUDENTS Artists can use almost any material to create a work of art. When an artist is deciding which material to use, he or she may consider how that particular material will help express his or her ideas. Where have students seen bronze before? Olympic medals, statues… Plaster? Casts for broken bones, texture or decoration on walls.. -

Public Art Implementation Plan

City of Alexandria Office of the Arts & the Alexandria Commission for the Arts An Implementation Plan for Alexandria’s Public Art Policy Submitted by Todd W. Bressi / Urban Design • Place Planning • Public Art Meridith C. McKinley / Via Partnership Elisabeth Lardner / Lardner/Klein Landscape Architecture Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction 2.0 Vision, Mission, Goals 3.0 Creative Directions Time and Place Neighborhood Identity Urban and Natural Systems 4.0 Project Development CIP-related projects Public Art in Planning and Development Special Initiatives 5.0 Implementation: Policies and Plans Public Art Policy Public Art Implementation Plan Annual Workplan Public Art Project Plans Conservation Plan 6.0 Implementation: Processes How the City Commissions Public Art Artist Identification and Selection Processes Public Art in Private Development Public Art in Planning Processes Donations and Memorial Artworks Community Engagement Evaluation 7.0 Roles and Responsibilities Office of the Arts Commission for the Arts Public Art Workplan Task Force Public Art Project Task Force Art in Private Development Task Force City Council 8.0 Administration Staffing Funding Recruiting and Appointing Task Force Members Conservation and Inventory An Implementation Plan for Alexandria’s Public Art Policy 2 Appendices A1 Summary Chart of Public Art Planning and Project Development Process A2 Summary Chart of Public Art in Private Development Process A3 Public Art Policy A4 Survey Findings and Analysis An Implementation Plan for Alexandria’s Public Art Policy 3 1.0 Introduction The City of Alexandria’s Public Art Policy, approved by the City Council in October 2012, was a milestone for public art in Alexandria. That policy, for the first time, established a framework for both the City and private developers to fund new public art projects. -

Cubo-Futurism

Notes Cubo-Futurism Slap in theFace of Public Taste 1 . These two paragraphs are a caustic attack on the Symbolist movement in general, a frequent target of the Futurists, and on two of its representatives in particular: Konstantin Bal'mont (1867-1943), a poetwho enjoyed enormouspopu larityin Russia during thefirst decade of this century, was subsequentlyforgo tten, and died as an emigrein Paris;Valerii Briusov(18 73-1924), poetand scholar,leader of the Symbolist movement, editor of the Salles and literary editor of Russum Thought, who after the Revolution joined the Communist party and worked at Narkompros. 2. Leonid Andreev (1871-1919), a writer of short stories and a playwright, started in a realistic vein following Chekhov and Gorkii; later he displayed an interest in metaphysicsand a leaning toward Symbolism. He is at his bestin a few stories written in a realistic manner; his Symbolist works are pretentious and unconvincing. The use of the plural here implies that, in the Futurists' eyes, Andreev is just one of the numerousepigones. 3. Several disparate poets and prose writers are randomly assembled here, which stresses the radical positionof the signatories ofthis manifesto, who reject indiscriminately aU the literaturewritt en before them. The useof the plural, as in the previous paragraphs, is demeaning. Maksim Gorkii (pseud. of Aleksei Pesh kov, 1�1936), Aleksandr Kuprin (1870-1938), and Ivan Bunin (1870-1953) are writers of realist orientation, although there are substantial differences in their philosophical outlook, realistic style, and literary value. Bunin was the first Rus sianwriter to wina NobelPrize, in 1933.AJeksandr Biok (1880-1921)is possiblythe best, and certainlythe most popular, Symbolist poet. -

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice PUBLICATIONS COORDINATION: Dinah Berland EDITING & PRODUCTION COORDINATION: Corinne Lightweaver EDITORIAL CONSULTATION: Jo Hill COVER DESIGN: Jackie Gallagher-Lange PRODUCTION & PRINTING: Allen Press, Inc., Lawrence, Kansas SYMPOSIUM ORGANIZERS: Erma Hermens, Art History Institute of the University of Leiden Marja Peek, Central Research Laboratory for Objects of Art and Science, Amsterdam © 1995 by The J. Paul Getty Trust All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-89236-322-3 The Getty Conservation Institute is committed to the preservation of cultural heritage worldwide. The Institute seeks to advance scientiRc knowledge and professional practice and to raise public awareness of conservation. Through research, training, documentation, exchange of information, and ReId projects, the Institute addresses issues related to the conservation of museum objects and archival collections, archaeological monuments and sites, and historic bUildings and cities. The Institute is an operating program of the J. Paul Getty Trust. COVER ILLUSTRATION Gherardo Cibo, "Colchico," folio 17r of Herbarium, ca. 1570. Courtesy of the British Library. FRONTISPIECE Detail from Jan Baptiste Collaert, Color Olivi, 1566-1628. After Johannes Stradanus. Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum-Stichting, Amsterdam. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Historical painting techniques, materials, and studio practice : preprints of a symposium [held at] University of Leiden, the Netherlands, 26-29 June 1995/ edited by Arie Wallert, Erma Hermens, and Marja Peek. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-89236-322-3 (pbk.) 1. Painting-Techniques-Congresses. 2. Artists' materials- -Congresses. 3. Polychromy-Congresses. I. Wallert, Arie, 1950- II. Hermens, Erma, 1958- . III. Peek, Marja, 1961- ND1500.H57 1995 751' .09-dc20 95-9805 CIP Second printing 1996 iv Contents vii Foreword viii Preface 1 Leslie A. -

Kansas Curricular Standards for Visual Arts Are Aligned with the National Standards for the Visual Arts

Model Curricular Standards for Visual Arts State Board of Education May 2007 Kansas Curricular Standards for Visual Arts Joyce Huser Fine Arts Education Consultant Kansas State Department of Education 120 Southeast 10th Avenue, Topeka, Kansas, 66612-1182 [email protected] (785) 296-4932 Table of Contents Mission Statement ii Introduction iii Acknowledgements iv Document Usage v Major Objectives of Art Education vi What Constitutes a Quality Art Education? vii Standards, Benchmarks, Indicators, Instructional Samples 1 Basic 2 Intermediate 24 Proficient 46 Advanced 68 Exemplary 90 Scope and Sequence 112 Appendix I 128 Blooms Taxonomy 129 Assessments in Art 135 Kansas Art Teacher Licensure Standards 139 Competitions and Contests 142 Displaying Artwork 144 Shooting Slides of Student Work 145 Museums 146 Needs of Special Students 147 A Safe Work Environment 149 Stages of Artistic Development 151 Technology Time and Scheduling Standards 153 Appendix II 156 Resources/Books 157 Websites 159 Art Museums in Kansas with Educational Materials 162 Appendix III 165 Lesson Plans 166 Appendix IV 253 Glossary 254 i The Mission of the Kansas Curriculum Standards for the Visual Arts The visual arts are a vital part of every Kansas student’s comprehensive education. ii Introduction The Kansas Curricular Standards for the Visual Arts are designed for all visual art students and educators whether experienced or in the preservice years of their teaching career. A range of benchmarks engages students in reaching their greatest potential in the visual arts. Quality activities involve students in thoughtful, creative, and original expression of self. In all cases, students will learn life-skills including critical thinking, astute observation, viewing from multiple perspectives, higher order learning, and authentic problem-solving skills. -

Tubular Sculptures

Tubular Sculptures Carlo H. Séquin CS Division, University of California, Berkeley, CA E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This paper reviews ways in which many artists have constructed large sculptures from tubular elements, ranging from single cylinders to toroidal or knotted structures, to assemblies of a large number of bent tubes. A few parameterized generators are introduced that facilitate design and evaluation of a variety of such sculptural forms. 1. Introduction Artists like Charles O. Perry have been able to build very large scale sculptures filling volumes of more than 30 feet in diameter at an affordable price by assembling pre-cut and bent tubular pieces. Stellar examples are Eclipse in the Hyatt Regency lobby in San Francisco, or Equinox at the Lincoln Center, Dallas, Texas (Fig.1a). But even much smaller assemblies of tubular elements can make very attractive sculptures. At the small end of this spectrum we find sculptures by Max Bill, e.g., Assembly of three equal cylinders (Fig.1b) [2], or the elegant tubular loops by José de Rivera (Fig.1c) [4]. Additional “minimal sculptures” will be discussed in Section 3. Figure 1: (a) Charles O. Perry: “Equinox;” (b) Max Bill: “Assembly of 3 equal cylinder;” (c) José de Rivera: “Construction #35.” With so many diverse ways of forming attractive sculptures from tubular elements, it seems worthwhile to try to compile an organized overview over the many possibilities and approaches used, and to explore in which ways computer-aided tools may be helpful to create additional, and potentially more complex, artistic structures. In addition, I have a personal, nostalgic reason to write this paper on Tubular Sculptures. -

ART the Art Model's Handbook

ART The Art Model’s Handbook: The Naked Truth about Posing for Art Classes and Fine Artists Andrew Cahner CreateSpace Softcover $16.95 (141pp) 978-1-442-16969-2 “The human form is arguably the most difficult subject for an artist to render,” writes author and experienced art model, Andrew Cahner. “A landscape drawn a little inaccurately will still look like a landscape, but an error in depicting a human likeness will not look right.” Capturing an emotional quality is even more challenging, writes Cahner, adding that mastering figure drawing skills prepares artists to draw all other subjects with ease. Given the importance of live models to this endeavor, it is strange that so little attention has been paid to their training and that few resources exist to orient art school faculty, art model coordinators, and artists themselves. Cahner, an experienced professional art model, has ably filled the gap with The Art Model’s Handbook; going beyond basic modeling and drawing terminology and technique, he describes how the model is an active participant in the creative process of figurative artists, providing not just a visual reference, but also serving as a source of inspiration. Recognizing that, especially in American culture, body issues can deter potentially great models from ever pursuing the career, Cahner explains the difference between fashion modeling, with its need for models whose bodies share a particular idealized form, and art modeling, which requires people of all sizes, shapes, ages, and races. With sensitivity and skill, the author describes what the figure drawing experience is like for both models and artists, and establishes the parameters of mutual respect and concern that must exist between them. -

A Data Set and a Convolutional Model for Iconography Classification in Paintings

111 A Data Set and a Convolutional Model for Iconography Classification in Paintings FEDERICO MILANI and PIERO FRATERNALI, Politecnico di Milano Iconography in art is the discipline that studies the visual content of artworks to determine their motifs and themes and to characterize the way these are represented. It is a subject of active research for a variety of purposes, including the interpretation of meaning, the investigation of the origin and diffusion in time and space of representations, and the studyof influences across artists and art works. With the proliferation of digital archives of art images, the possibility arises ofapplying Computer Vision techniques to the analysis of art images at an unprecedented scale, which may support iconography research and education. In this paper we introduce a novel paintings data set for iconography classification and present the quantitative and qualitative results of applying a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) classifier to the recognition of the iconography of artworks. The proposed classifier achieves good performances (71.17% Precision, 70.89% Recall, 70.25% F1-Score and 72.73% Average Precision) in the task of identifying saints in Christian religious paintings, a task made difficult by the presence of classes with very similar visual features. Qualitative analysis of the results shows that the CNN focuses on the traditional iconic motifs that characterize the representation of each saint and exploits such hints to attain correct identification. The ultimate goal of our work is to enable the automatic extraction, decomposition, and comparison of iconography elements to support iconographic studies and automatic art work annotation. CCS Concepts: • Computing methodologies ! Artificial intelligence; Computer vision; Computer vision tasks; Computer vision problems; • Applied computing ! Arts and humanities; Additional Key Words and Phrases: Iconography, Art, Paintings, Data set, Deep learning, Classification, Transfer learning ACM Reference Format: Federico Milani and Piero Fraternali. -

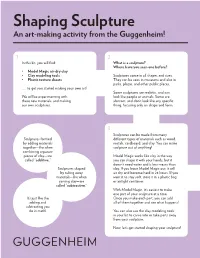

Shaping Sculpture an Art-Making Activity from the Guggenheim!

Shaping Sculpture An art-making activity from the Guggenheim! In this kit, you will find: What is a sculpture? Where have you seen one before? • Model Magic air-dry clay • Clay modeling tools Sculptures come in all shapes and sizes. • Plastic texture sheets They can be seen in museums and also in parks, plazas, and other public places. to get you started making your own art! Some sculptures are realistic, and can We will be experimenting with look like people or animals. Some are these new materials, and making abstract, and don’t look like any specific our own sculptures. thing, focusing only on shape and form. Sculptures can be made from many Sculptures formed different types of materials such as wood, by adding materials metals, cardboard, and clay. You can make together—like when sculpture out of anything! combining separate pieces of clay—are Model Magic works like clay in the way called “additive.” you can shape it with your hands, but it doesn’t need water and is less messy than Sculptures shaped clay. If you leave Model Magic out, it will by taking away air dry and become hard in 24 hours. If you materials—like when want it to stay soft, store it in a plastic bag carving clay—are or airtight container. called “subtractive.” With Model Magic, it’s easiest to make one part of your sculpture at a time. It’s just like the Once you make each part, you can add adding and all of them together and see what happens! subtracting you do in math! You can also use the clay modeling tools in your kit to carve into or take parts away from your sculpture. -

Ceramic Sculpture 1 Art 3764C

Ceramic Sculpture 1 Art 3764C Fall, 2018 Tuesday& Thursday Class Times: 11:45 am- 2:45 am (periods 5-7) Classroom: FAC B14 Instructor: Nan Smith, Professor (GTA: Cindy Leung) Office: FAC B15, Hours: 3:00pm-4:00 pm on Thursdays or by appointment E-mail: [email protected] Credit Hours - 03 Room Code – B14 : 1358* Syllabus Course Description: This course provides an introduction to Ceramic Sculpture with a specific focus on hand building processes. Contemporary Ceramics is an expansive art form including pottery and vessel making, sculptural works and painted tile work. The options for working with fired clay are limitless and the technical subject matter complex. Sculptures created in fired clay will be created using varied techniques to convey ideas based personal viewpoints about contemporary culture. Mid to large scale ceramic sculptures will be encouraged. Sculpture processes which are additive and subtractive, plus pinch, coil building, and slab construction methods as applied to sculpting will be taught. The basics of plaster mold-making will be introduced. Technology will be introduced through as use of china paint decal imagery reproducing drawings, paintings, and photography onto the surfaces of sculpture. Glaze lectures, an introduction to electric kiln firing will also be presented. Projects focus on the use of low-fire materials, conveying ideas, image development and glaze electric fired to enhance sculpture in service of content. Each project will allow students to explore their world creatively by researching topics to inform project solutions. The class format will include image presentations and demonstrations of hand building and sculpture techniques. Class lectures will incorporate highlights from ceramic history along with many contemporary examples. -

Nude in a Classroom: the Contemporary World of Life Modelling

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2019 Nude in a Classroom: The Contemporary World of Life Modelling Kannaki Bharali The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3019 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] NUDE IN A CLASSROOM: THE CONTEMPORARY WORLD OF LIFE MODELLING by KANNAKI BHARALI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Sociology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2019 © 2019 KANNAKI BHARALI All Rights Reserved ii Nude in a Classroom: The Contemporary World of Life Modelling by Kannaki Bharali This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Sociology in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Philip Kasinitz Chair of Examining Committee Date Lynn Chancer Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Cynthia Epstein David Halle Elizabeth Wissinger THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Nude in a classroom: The Contemporary World of Life Modelling by Kannaki Bharali Advisor: Dr. Phillip Kasinitz Throughout the history of Western art, drawing from live nude models has been considered one of the most efficient way to develop artistic skills. While drawing live nudes used to be something one had to enroll in an art school to do, life drawing has now transformed to a leisure practice across widely diverse cultural groups. -

WHAT IS SLOW ART? (When Images Swell Into Events and Events Condense Into Images)

1 WHAT IS SLOW ART? (When Images Swell into Events and Events Condense into Images) Is a picture made in a single moment? No, it is built up piece-by-piece, just like a house. And the spectator—is his looking done in a single moment? PAUL KLEE1 I am looking for a field that will frame the formative experiences I’ve invoked—gazing at an Édouard Manet painting, watching the sunset from the slope of an extinct volcano, wandering through a Cor-Ten spiral on a midwestern evening. To qualify as a category, slow art requires shape and coherence—but not too much of either, as that could blunt the particularities that make such encounters noteworthy in the first place. Further, slow art has no “essence”; rather, it names social, time-bound experiences. Slow art is plural. It can be demanding or easy to access, avant-garde or homespun populist, refined or vulgar, chaste or salacious, as cool as Thomas Struth’s video portraits or as kitsch as a waxwork Sleeping Beauty with a beating heart. Again, what counts as slow for you might not for me. Notice that not all art registers as either fast or slow. In many cases, if not most, tempo and duration hardly solicit our attention. The test of a good Hollywood “entertainment,” for instance, is not checking your watch. To fit our category, then, experiences must be coded as culturally slow, must make us say to ourselves, “Oh, this feels drawn out”—even at the risk of boring us. Herein lies the deeper divide: on one hand aesthetic forms in which time is neutral or invisible; on the other those in which tempo, whether fast or slow, makes itself integral to the work.