Vanity Fair, March 2016. Robert Mapplethorpe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

My Back Pages #1

My Back Pages #1 L’iMMaginario coLLettivo deL rock neLLe fotografie di Ed CaraEff, HEnry diltz, HErb GrEEnE, Guido Harari, art KanE, astrid KirCHHErr, Jim marsHall, norman sEEff e bob sEidEmann 04.02 | 11.03.2012 Wall of sound gallery La capsula del tempo decolla… La musica non è solo suono, ma anche immagine. Senza le visioni di questi fotografi, non avremmo occhi per guardare la musica. Si può ascoltare e “ca- pire” Jimi Hendrix senza vedere la sua Stratocaster in fiamme sul palco di Monterey, fissata per sempre da Ed Caraeff? O intuire fino in fondo la deriva amara di Janis Joplin senza il crudo bianco e nero di Jim Marshall che ce la mostra affranta con l’inseparabile bottiglia di Southern Comfort in mano? Nasce così l’immaginario collettivo del rock, legato anche a centinaia di co- pertine di dischi. In questa mostra sfilano almeno una dozzina di classici: dagli album d’esordio di Crosby Stills & Nash e di Stephen Stills in solitario a Morrison Hotel dei Doors, The Kids Are Alright degli Who, al primo disco americano dei Beatles per l’etichetta VeeJay, Hejira di Joni Mitchell, Surre- alistic Pillow dei Jefferson Airplane, Grateful Dead di Jerry Garcia e compa- gni, Genius Loves Company di Ray Charles, Stage Fright della Band di Robbie Robertson, Desperado degli Eagles e Hotter Than Hell dei Kiss. Il tempismo è tutto. Soprattutto trovarsi come per miracolo all’inizio di qualcosa, ad una magica intersezione col destino che può cambiare la vita di entrambi, fotografo e fotografato. Questo è successo ad astrid Kirchherr con i Beatles ancora giovanissimi ad Amburgo, o a Herb Greene immerso nella ribollente “scena” musicale di San Francisco. -

Mapplethorpe: Assault with a Deadly Camera

How To Quote This Material ©Jack Fritscher www.JackFritscher.com Mapplethorpe: Assault with a Deadly Camera — Take 2: Pentimento for Robert Mapplethorpe Manuscript TAKE 2 © JackFritscher.com PENTIMENTO FOR ROBERT MAPPLETHORPE FETISHES, FACES, AND FLOWERS Of EVIL1 “He wanted to see the devil in us all... The man who liberated S&M Leather into international glamor... The man Jesse Helms hates... The man whose epic movie-biography only Ken Russell could re-create...” Photographer Mapplethorpe: The Whitney, the NEA and censorship, Schwarzenegger, Richard Gere, Susan Sarandon, Paloma Picasso, Hockney, Warhol, Patti Smith, Scavullo, sex, drugs, rock ’n’ roll, S&M, flowers, black leather, fists, Allen Ginsberg, and, once-upon-a-time, me... The pre-AIDS past of the 1970s has become a strange country. We lived life differently a dozen years ago. The High Time was in full upswing. Liberation was in the air, and so were we, performing nightly our high-wire sex acts in a circus without nets. If we fell, we fell with splendor in the grass. That carnival, ended now, has no more memory than the remembrance we give it, and we give remembrance here. In 1977, Robert Mapplethorpe arrived unexpectedly in my life. I was editor of the San Francisco—based international leather magazine, Drummer, and Robert was a New York shock-and-fetish photographer on the way up. Drummer wanted good photos. Robert, already infamous for his leather S&M portraits, always seeking new models with outrageous trips, wanted more specific exposure within the leather community. Our mutual, professional want ignited almost instantly into mutual, personal passion. -

A Finding Aid to the Samuel J. Wagstaff Papers, Circa 1932-1985, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Samuel J. Wagstaff Papers, circa 1932-1985, in the Archives of American Art Catherine S. Gaines Funding for the digitization of this collection was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art December 13, 2006 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical Note............................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Correspondence, 1932-1986.................................................................... 5 Series 2: Writings, 1961-1983................................................................................ 25 Series 3: Miscellaneous Papers and Artifacts, -

CHILLED CAVIAR to EAT... a Little More Naked... VEGETABLES and MORE... FLOUR and WATER

CHILLED VEGETABLES AND MORE... TO EAT... (V) Garden Vegetable Crudités 18 (V) Coleman Farm's Garden Green Salad 22 • (VG) Austrian White Asparagus 32 Santa Monica Farmers' Market Seasonal Harvest Heirloom Lettuces, Spring Citrus, Meyer Lemon Vinaigrette Sun-Dried Tomato Chimichurri, Marinated Quinoa and Spring Vegetables, Sunflower Seeds Cilantro Green Goddess Dressing Toasted Black Olive Crostini with Local Goat Cheese Alaskin Halibut 49* Baja Gulf Prawns 36 (V) Imported Italian Burrata 18 Pan-Roasted, Braised Baby Artichokes, Confit Fennel, Lemon Purée, Herb Gremolata Spicy Horseradish, Citrus Tomato Sauce 18-Year Aged Balsamic Vinegar, Grilled Country White Bread Toasted Pepitas, Foraged Herbs • Organic Jidori Half Chicken 54 Whole Santa Barbara Uni 24* Porcini Mushrooms, Romano Beans, Natural Jus Tomato, Red Onion, Micro Shiso (V) Caramelized Corn Salad 24 First of the Season White Corn, Frijoles, Cherry Tomatoes • 8oz USDA Prime 'Butcher's Butter' 76* Kusshi Oysters 24/48* Wild Arugula, Cilantro Crema, Black Lime Vinaigrette Pommes Aligot, Sauce Armagnac British Columbia, Clean, Mildly Sweet, Slightly Meaty Green Apple Fennel-Mignonette (V) Green Asparagus Soup 22 (WP) Marcho Farms Veal 'Wiener Schnitzel' 49* White Asparagus, Meyer Lemon Oil Marinated Fingerling Potatoes, Marinated Cherry Tomatoes, Styrian Pumpkin Seed Oil Omega Blue Kanpachi Tataki Crudo 32* Carrot Aguachile, Pickled Green Almonds, Charred Scallion • CAB 'Never Ever' Beef Burger 28* Japanese Cucumber, Avocado, Coriander FLOUR AND WATER Vermont White Cheddar, Garlic -

Art in America, March 1, 2016. Robert Mapplethorpe

Reid-Pharr, Robert. “Putting Mapplethorpe In His Place,” Art in America, March 1, 2016. Robert Mapplethorpe: Self-Portrait, 1988, platinum print, 23⅛ by 19 inches. With a retrospective for the celebrated photographer about to open at two Los Angeles institutions, the author reassesses the 1990 “X Portfolio” obscenity trial, challenging its distinction between fine art and pornography. Americans take their art seriously. Stereotypes about Yankee simplicity and boorishness notwithstanding, we are a people ever ready to challenge each other’s tastes and orthodoxies. And though we always seem surprised when it happens, we can quite efficiently use the work of artists as screens against which to project deeply entrenched phobias regarding the nature of our society and culture. In hindsight it really was no surprise that the traveling retrospective “Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Moment” would so fiercely grip the imaginations of artists, critics, politicians and laypersons alike. Curated by Janet Kardon of the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in Philadelphia, the exhibition opened in December of 1988, just before the artist’s death in March of 1989. It incorporated some of Mapplethorpe’s best work, including stunning portraits and still lifes. What shocked and irritated some members of his audiences, however, were photographs of a naked young boy and a semi-naked girl as well as richly provocative erotic images of African-American men and highly stylized photographs of the BDSM underground in which Mapplethorpe participated. Indeed, much of what drew such concentrated attention to Mapplethorpe was the delicacy and precision with which he treated his sometimes challenging subject matter. -

Course Reader

Media Studies: Archives & Repertoires Mariam Ghani / Spring 2016 COURSE READER • Michel Foucault, “The historical a priori and the archive” from The Archeology of Knowledge (1971) • Giorgio Agamben, “The Archive and Testimony” from Remnants of Auschwitz (1989) • Giorgio Agamben, “The Witness” from Remnants of Auschwitz (1989) • Mariam Ghani, “Field notes for 'What we left unfnished': The Artist and the Archive” (Ibraaz, 2014) * recommended • Jacques Derrida, “Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression” (Diacritics, 1995) • Alan Sekula, “The Body and the Archive” (October, 1986) • Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History” (1937) • Alan Sekula, “Reading an Archive” from The Photography Reader (1983) *recommended • Hal Foster, “An Archival Impulse” (October, 2007) *recommended • Okwui Enwezor, “Archive Fever: Photography Between History & the Monument” (2007) * recommended • Matthew Reason, “Archive or Memory? The Detritus of Live Performance” (New Theatre Quarterly, 2003) • Xavier LeRoy, “500 Words” (Artforum, 2014) • “Bird of a Feather: Jennifer Monson's Live Dancing Archive” (Brooklyn Rail, 2014) • Gia Kourlas, “Q&A with Sarah Michelson” (Time Out NY, 2014) • Gillian Young, “Trusting Clifford Owens: Anthology at MoMA/PS1” (E-misférica, 2012) • “The Body as Object of Interference: Q&A with Jeff Kolar” (Rhizome, 2014) *rec • Anthology roundtable from the Radical Presence catalogue (2015) *rec • Pad.ma, “10 Theses on the Archive” (2010) • Ann Cvetkovich, “The Queer Art of the Counter-Archive” from Cruising the Archive (2014) • Diana -

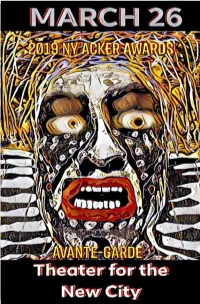

NY ACKER Awards Is Taken from an Archaic Dutch Word Meaning a Noticeable Movement in a Stream

1 THE NYC ACKER AWARDS CREATOR & PRODUCER CLAYTON PATTERSON This is our 6th successful year of the ACKER Awards. The meaning of ACKER in the NY ACKER Awards is taken from an archaic Dutch word meaning a noticeable movement in a stream. The stream is the mainstream and the noticeable movement is the avant grade. By documenting my community, on an almost daily base, I have come to understand that gentrification is much more than the changing face of real estate and forced population migrations. The influence of gen- trification can be seen in where we live and work, how we shop, bank, communicate, travel, law enforcement, doctor visits, etc. We will look back and realize that the impact of gentrification on our society is as powerful a force as the industrial revolution was. I witness the demise and obliteration of just about all of the recogniz- able parts of my community, including so much of our history. I be- lieve if we do not save our own history, then who will. The NY ACKERS are one part of a much larger vision and ambition. A vision and ambition that is not about me but it is about community. Our community. Our history. The history of the Individuals, the Outsid- ers, the Outlaws, the Misfits, the Radicals, the Visionaries, the Dream- ers, the contributors, those who provided spaces and venues which allowed creativity to flourish, wrote about, talked about, inspired, mentored the creative spirit, and those who gave much, but have not been, for whatever reason, recognized by the mainstream. -

© 2016 Mary Kate Scott ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

© 2016 Mary Kate Scott ALL RIGHTS RESERVED THE PHOTOGRAPHY OF ABSENCE: DEATH IN POSTMODERN AMERICA By MARY KATE SCOTT A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Art History Written under the direction of Andrés Zervigón And approved by ________________________________________ ________________________________________ ________________________________________ ________________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey January 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Photography of Absence: Death in Postmodern America By MARY KATE SCOTT Dissertation Director: Dr. Andrés Zervigón It is a paradox that postmodern photographic theory—so thoroughly obsessed with death—rarely addresses intimate scenes of explicit death or mortality. Rather, it applies these themes to photographs of living subjects or empty spaces, laying upon each image a blanket of pain, loss, or critical dissatisfaction. Postmodern theorists such as Rosalind Krauss and Geoffrey Batchen root their work in the writings of Roland Barthes, which privilege a photograph’s viewer over its subject or maker. To Barthes’ followers in the 1980s and 1990s, the experiences depicted within the photograph were not as important as our own relationships with it, in the present. The photographers of the Pictures Generation produced groundbreaking imagery that encouraged the viewer to question authority, and even originality itself. Little was said, though, about intimacy, beauty, the actual fact of death, or the author’s individual experience. However, a significant group of American art photographers at the end of the twentieth century began making works directly featuring their own personal experiences with mortality. -

Triptych Eyes of One on Another

Saturday, September 28, 2019, 8pm Zellerbach Hall Triptych Eyes of One on Another A Cal Performances Co-commission Produced by ArKtype/omas O. Kriegsmann in cooperation with e Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation Composed by Bryce Dessner Libretto by korde arrington tuttle Featuring words by Essex Hemphill and Patti Smith Directed by Kaneza Schaal Featuring Roomful of Teeth with Alicia Hall Moran and Isaiah Robinson Jennifer H. Newman, associate director/touring Lilleth Glimcher, associate director/development Brad Wells, music director and conductor Martell Ruffin, contributing choreographer and performer Carlos Soto, set and costume design Yuki Nakase, lighting design Simon Harding, video Dylan Goodhue/nomadsound.net, sound design William Knapp, production management Talvin Wilks and Christopher Myers, dramaturgy ArKtype/J.J. El-Far, managing producer William Brittelle, associate music director Kathrine R. Mitchell, lighting supervisor Moe Shahrooz, associate video designer Megan Schwarz Dickert, production stage manager Aren Carpenter, technical director Iyvon Edebiri, company manager Dominic Mekky, session copyist and score manager Gill Graham, consulting producer Carla Parisi/Kid Logic Media, public relations Cal Performances’ 2019 –20 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. ROOMFUL OF TEETH Estelí Gomez, Martha Cluver, Augusta Caso, Virginia Kelsey, omas McCargar, ann Scoggin, Cameron Beauchamp, Eric Dudley SAN FRANCISCO CONTEMPORARY MUSIC PLAYERS Lisa Oman, executive director ; Eric Dudley, artistic director Susan Freier, violin ; Christina Simpson, viola ; Stephen Harrison, cello ; Alicia Telford, French horn ; Jeff Anderle, clarinet/bass clarinet ; Kate Campbell, piano/harmonium ; Michael Downing and Divesh Karamchandani, percussion ; David Tanenbaum, guitar Music by Bryce Dessner is used with permission of Chester Music Ltd. “e Perfect Moment, For Robert Mapplethorpe” by Essex Hemphill, 1988. -

Andy Warhol: When Junkies Ruled the World

Nebula 2.2 , June 2005 Andy Warhol: When Junkies Ruled the World. By Michael Angelo Tata So when the doorbell rang the night before, it was Liza in a hat pulled down so nobody would recognize her, and she said to Halston, “Give me every drug you’ve got.” So he gave her a bottle of coke, a few sticks of marijuana, a Valium, four Quaaludes, and they were all wrapped in a tiny box, and then a little figure in a white hat came up on the stoop and kissed Halston, and it was Marty Scorsese, he’d been hiding around the corner, and then he and Liza went off to have their affair on all the drugs ( Diaries , Tuesday, January 3, 1978). Privileged Intake Of all the creatures who populate and punctuate Warhol’s worlds—drag queens, hustlers, movie stars, First Wives—the drug user and abuser retains a particular access to glamour. Existing along a continuum ranging from the occasional substance dilettante to the hard-core, raging junkie, the consumer of drugs preoccupies Warhol throughout the 60s, 70s and 80s. Their actions and habits fascinate him, his screens become the sacred place where their rituals are projected and packaged. While individual substance abusers fade from the limelight, as in the disappearance of Ondine shortly after the commercial success of The Chelsea Girls , the loss of status suffered by Brigid Polk in the 70s and 80s, or the fatal overdose of exemplary drug fiend Edie Sedgwick, the actual glamour of drugs remains, never giving up its allure. 1 Drugs survive the druggie, who exists merely as a vector for the 1 While Brigid Berlin continues to exert a crucial influence on Warhol’s work in the 70s and 80s—for example, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol , as detailed by Bob Colacello in the chapter “Paris (and Philosophy )”—her street cred. -

Album Cover Art Price Pages.Key

ART OF THE ALBUM COVER SAN FRANCISCO ART EXCHANGE LLC Aretha Franklin, Let Me In Your Life Front Cover, 1974 $1,500 by JOEL BRODSKY (1939-2007) Not including frame Black Sabbath, Never Say Die Album Cover, 1978 NFS by HIPGNOSIS 1968-1983 Blind Faith Album Cover, London, 1969 $17,500 by BOB SEIDEMANN (1941-2017) Not including frame Bob Dylan & Johnny Cash Performance, The Dylan Cash Session Album Cover, 1969 $1,875 by JIM MARSHALL (b.1936 - d.2010) Not including frame Bob Dylan, Blonde on Blonde Album Cover, NYC, 1966 $25,000 by JERRY SCHATZBERG (b.1927) Not including frame Bob Dylan, Greatest Hits Album Cover, Washington DC, 1965 $5,000 by ROWLAND SCHERMAN (b.1937) Not including frame Bob Dylan, Nashville Skyline Album Cover, 1969 $1,700 by ELLIOT LANDY (b.1942) Not including frame Booker T & the MGs, McLemore Ave Front Cover Outtake, 1970 $1,500 by JOEL BRODSKY (1939-2007) Not including frame Bruce Springsteen, As Requested Around the World Album Cover, 1979 $2,500 by JOEL BERNSTEIN (b.1952) Not including frame Bruce Springsteen, Hungry Heart 7in Single Sleeve, 1980 $1,500 by JOEL BERNSTEIN (b.1952) Not including frame Carly Simon, Playing Possum Album Cover, Los Angeles, 1974 $3,500 by NORMAN SEEFF (b.1939) Not including frame Country Joe & The Fish, Fixin’ to Die Back Cover Outtake, 1967 $7,500 by JOEL BRODSKY (1939-2007) Not including frame Cream, Best of Cream Back Cover Outtake, 1967 $6,000 by JIM MARSHALL (b.1936 - d.2010) Not including frame Cream, Best of Cream Back Cover Outtake, 1967 Price on Request by JIM MARSHALL (b.1936 -

Robert Mapplethorpe

GALERIE THADDAEUS ROPAC ROBERT MAPPLETHORPE ROBERT MAPPLETHORPE CURATED BY HEDI SLIMANE PARIS DEBELLEYME 13 Thursday - 19 Saturday The Thaddaeus Ropac Gallery is pleased to present an important exhibition of works by American photographer Robert Mapplethorpe. Hedi Slimane, the artistic director of Dior Homme, also a photographer in his own right, will curate the show. The concept of the show is to invite a contemporary artist to rediscover a major body of work such as Mapplethorpe's, by reframing the whole, based on his own sensibilities and tastes thus helping us to view the renowned works in a new light. This show follows in the footsteps of a series of exhibits. Previous shows include- « Robert Mapplethorpe: Eye to Eye » organized in 2003 by the American artist Cindy Sherman in New York, as well as the exhibit « Robert Mapplethorpe curated by David Hockney » which took place in London in early 2005. Both Slimane and Mapplethorpe share a passion for photography, and both, by different means, each in his own generation, have defined the mood and aesthetic of the artistic community to which they belong. Hedi Slimane has been given free reign to explore themes that inspire him in Mapplethorpe's work. Last May, in conjunction with the release of his book of photographs of rocks bands, Slimane also edited the layout for the daily paper Libération. We can expect to find, in his selection of works for the show, images that reflect themes in both he and Mapplethorpe's lives where their sensibilities, moods and observations converge. By offering this face-to-face between two creative forces, this event allows us to revisit the work in an intimate, rather than critical manner.