Localised Declines in Colonies of the Short-Tailed Shearwater: an Explanation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bruny Island Tasmania 15–21 February 2016

Bruny Island Tasmania 15–21 February 2016 Bush Blitz Species Discovery Program Bruny Island, Tasmania 15–21 February 2016 What is Bush Blitz? Bush Blitz is a multi-million dollar partnership between the Australian Government, BHP Billiton Sustainable Communities and Earthwatch Australia to document plants and animals in selected properties across Australia. This innovative partnership harnesses the expertise of many of Australia’s top scientists from museums, herbaria, universities, and other institutions and organisations across the country. Abbreviations ABRS Australian Biological Resources Study AFD Australian Faunal Directory ALA Atlas of Living Australia ANIC Australian National Insect Collection CA Conservation Area DPIPWE Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment (Tasmania) EPBC Act Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Commonwealth) MPA Marine Protected Area QM Queensland Museum RTBG Royal Tasmanian Botanical Gardens TMAG Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery TSP Act Threatened Species Protection Act 1995 (Tasmania) UNSW University of New South Wales Page 2 of 40 Bruny Island, Tasmania 15–21 February 2016 UTas University of Tasmania Page 3 of 40 Bruny Island, Tasmania 15–21 February 2016 Summary A Bush Blitz expedition was conducted on Bruny Island, Tasmania, between 15 and 21 February 2016. The study area included protected areas on Bruny Island and parts of the surrounding marine environment. Bruny Island includes a wide diversity of micro-climates and habitat types. It is home to a number of species that are found only in Tasmania, including several threatened plant and animal species. In addition to its significant natural heritage, the island is the traditional land of the Nununi people and contains many sites of cultural significance. -

Rti-Dl-Release-Dpipwe

Assessed by the Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment under the Right to Information Act 2009 RTI 039 Authorisation Type Species Basis of sustainability assessment CPP/Game Bennett’s • Annual spotlight monitoring of 190 x 10km transects Licence/Commercial and Rufous across Tasmania: Hunting Licence wallaby https://dpipwe.tas.gov.au/Documents/Spotlight%20Su mmary%20Report.pdf CPP Black • Case by case assessment of the impacts of species Currawong • As take is estimated at less than 5% per year, the population is therefore not monitored. CPP Black Swan • Annual monitoring on 75 wetlands across Tasmania: https://dpipwe.tas.gov.au/Documents/Statewide%20W aterbird%20Surveys.pdf CPP Black-faced • Case by case assessment of the impacts of species Cormorant • As take is estimated at less than 5% per year, the population is therefore not monitored. Game Licence Brown • Annual monitoring on 9 offshore islands of the Furneaux Quail Group where majority of harvesting occurs (graph attached). CPP/Commercial Brushtail • Annual spotlight monitoring of 190 x 10km transects possum across Tasmania: https://dpipwe.tas.gov.au/Documents/Spotlight%20Su mmary%20Report.pdf https://dpipwe.tas.gov.au/Documents/Management%2 0Plan%20for%20the%20Commercial%20Harvest%20&% 20Export%20of%20Brushtail%20Possums%20in%20Tas mania%202015-2020.pdf https://dpipwe.tas.gov.au/Documents/Commercial%20 Harvest%20Quota%20Report%20Brushtail%20Possum% 202019-20.pdf CPP Cape • Annual monitoring of gosling production and adult flock Barren size to set harvest/cull quota (graph attached). RTI-DL-RELEASE-DPIPWEGoose CPP/Game Licence Chestnut • Annual monitoring on 75 wetlands across Tasmania: Teal https://dpipwe.tas.gov.au/Documents/Statewide%20W aterbird%20Surveys.pdf CPP/Game Licence Common • Periodic monitoring of cock birds on King Island since Pheasant 1999 (graph attached). -

Great Australian Bight BP Oil Drilling Project

Submission to Senate Inquiry: Great Australian Bight BP Oil Drilling Project: Potential Impacts on Matters of National Environmental Significance within Modelled Oil Spill Impact Areas (Summer and Winter 2A Model Scenarios) Prepared by Dr David Ellis (BSc Hons PhD; Ecologist, Environmental Consultant and Founder at Stepping Stones Ecological Services) March 27, 2016 Table of Contents Table of Contents ..................................................................................................... 2 Executive Summary ................................................................................................ 4 Summer Oil Spill Scenario Key Findings ................................................................. 5 Winter Oil Spill Scenario Key Findings ................................................................... 7 Threatened Species Conservation Status Summary ........................................... 8 International Migratory Bird Agreements ............................................................. 8 Introduction ............................................................................................................ 11 Methods .................................................................................................................... 12 Protected Matters Search Tool Database Search and Criteria for Oil-Spill Model Selection ............................................................................................................. 12 Criteria for Inclusion/Exclusion of Threatened, Migratory and Marine -

Impact of Sea Level Rise on Coastal Natural Values in Tasmania

Impact of sea level rise on coastal natural values in Tasmania JUNE 2016 Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment Acknowledgements Thanks to the support we received in particular from Clarissa Murphy who gave six months as a volunteer in the first phase of the sea level rise risk assessment work. We also had considerable technical input from a range of people on various aspects of the work, including Hans and Annie Wapstra, Richard Schahinger, Tim Rudman, John Church, and Anni McCuaig. We acknowledge the hard work over a number of years from the Sea Level Rise Impacts Working Group: Oberon Carter, Louise Gilfedder, Felicity Faulkner, Lynne Sparrow (DPIPWE), Eric Woehler (BirdLife Tasmania) and Chris Sharples (University of Tasmania). This report was compiled by Oberon Carter, Felicity Faulkner, Louise Gilfedder and Peter Voller from the Natural Values Conservation Branch. Citation DPIPWE (2016) Impact of sea level rise on coastal natural values in Tasmania. Natural and Cultural Heritage Division, Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment, Hobart. www.dpipwe.tas.gov.au ISBN: 978-1-74380-009-6 Cover View to Mount Cameron West by Oberon Carter. Pied Oystercatcher by Mick Brown. The Pied Oystercatcher is considered to have a very high exposure to sea level rise under both a national assessment and Tasmanian assessment. Its preferred habitat is mudflats, sandbanks and sandy ocean beaches, all vulnerable to inundation and erosion. Round-leaved Pigface (Disphyma australe) in flower in saltmarsh at Lauderdale by Iona Mitchell. Three saltmarsh communities are associated with the coastal zone and are considered at risk from sea level rise. -

Biodiversity of Michigan's Great Lakes Islands

FILE COPY DO NOT REMOVE Biodiversity of Michigan’s Great Lakes Islands Knowledge, Threats and Protection Judith D. Soule Conservation Research Biologist April 5, 1993 Report for: Land and Water Management Division (CZM Contract 14C-309-3) Prepared by: Michigan Natural Features Inventory Stevens T. Mason Building P.O. Box 30028 Lansing, MI 48909 (517) 3734552 1993-10 F A report of the Michigan Department of Natural Resources pursuant to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Award No. 309-3 BIODWERSITY OF MICHIGAN’S GREAT LAKES ISLANDS Knowledge, Threats and Protection by Judith D. Soule Conservation Research Biologist Prepared by Michigan Natural Features Inventory Fifth floor, Mason Building P.O. Box 30023 Lansing, Michigan 48909 April 5, 1993 for Michigan Department of Natural Resources Land and Water Management Division Coastal Zone Management Program Contract # 14C-309-3 CL] = CD C] t2 CL] C] CL] CD = C = CZJ C] C] C] C] C] C] .TABLE Of CONThNTS TABLE OF CONTENTS I EXECUTIVE SUMMARY iii INTRODUCTION 1 HISTORY AND PHYSICAL RESOURCES 4 Geology and post-glacial history 4 Size, isolation, and climate 6 Human history 7 BIODWERSITY OF THE ISLANDS 8 Rare animals 8 Waterfowl values 8 Other birds and fish 9 Unique plants 10 Shoreline natural communities 10 Threatened, endangered, and exemplary natural features 10 OVERVIEW OF RESEARCH ON MICHIGAN’S GREAT LAKES ISLANDS 13 Island research values 13 Examples of biological research on islands 13 Moose 13 Wolves 14 Deer 14 Colonial nesting waterbirds 14 Island biogeography studies 15 Predator-prey -

Overview of Tasmania's Offshore Islands and Their Role in Nature

Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania, Volume 154, 2020 83 OVERVIEW OF TASMANIA’S OFFSHORE ISLANDS AND THEIR ROLE IN NATURE CONSERVATION by Sally L. Bryant and Stephen Harris (with one text-figure, two tables, eight plates and two appendices) Bryant, S.L. & Harris, S. 2020 (9:xii): Overview of Tasmania’s offshore islands and their role in nature conservation.Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania 154: 83–106. https://doi.org/10.26749/rstpp.154.83 ISSN: 0080–4703. Tasmanian Land Conservancy, PO Box 2112, Lower Sandy Bay, Tasmania 7005, Australia (SLB*); Department of Archaeology and Natural History, College of Asia and the Pacific, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 2601 (SH). *Author for correspondence: Email: [email protected] Since the 1970s, knowledge of Tasmania’s offshore islands has expanded greatly due to an increase in systematic and regional surveys, the continuation of several long-term monitoring programs and the improved delivery of pest management and translocation programs. However, many islands remain data-poor especially for invertebrate fauna, and non-vascular flora, and information sources are dispersed across numerous platforms. While more than 90% of Tasmania’s offshore islands are statutory reserves, many are impacted by a range of disturbances, particularly invasive species with no decision-making framework in place to prioritise their management. This paper synthesises the significant contribution offshore islands make to Tasmania’s land-based natural assets and identifies gaps and deficiencies hampering their protection. A continuing focus on detailed gap-filling surveys aided by partnership restoration programs and collaborative national forums must be strengthened if we are to capitalise on the conservation benefits islands provide in the face of rapidly changing environmental conditions and pressure for future use. -

Tasmanian Aborigines in the Furneaux Group in the Nine Teenth Century—Population and Land

‘I hope you will be my frend’: Tasmanian Aborigines in the Furneaux Group in the nine teenth century—population and land tenure Irynej Skira Abstract This paper traces the history of settlement of the islands of the Furneaux Group in Bass Strait and the effects of government regulation on the long term settlements of Tasma nian Aboriginal people from the 1850s to the early 1900s. Throughout the nineteenth century the Aboriginal population grew slowly eventually constituting approximately 40 percent of the total population of the Furneaux Group. From the 1860s outsiders used the existing land title system to obtain possession of the islands. Aborigines tried to establish tenure through the same system, but could not compete because they lacked capital, and were disadvantaged by isolation in their communication with gov ernment. Further, the islands' use for grazing excluded Aborigines who rarely had large herds of stock and were generally not agriculturalists. The majority of Aborigines were forced to settle on Cape Barren Island, where they built homes on a reserve set aside for them. European expansion of settlement on Flinders Island finally completed the disen franchisement of Aboriginal people by making the Cape Barren Island enclave depend ent on the government. Introduction In December 1869 Thomas Mansell, an Aboriginal, applied to lease a small island. He petitioned the Surveyor-General, T hope you will be my Frend...I am one of old hands Her, and haf Cast and have large family and no hum'.1 Unfortunately, he could not raise £1 as down payment. Mansell's was one of the many attempts by Aboriginal people in the Furneaux Group to obtain valid leasehold or freehold and recognition of their long term occupation. -

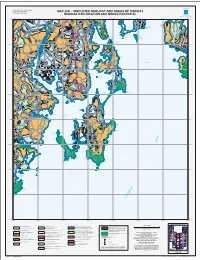

Map 20A − Simplified Geology and Areas of Highest

MINERAL RESOURCES TASMANIA MUNICIPAL PLANNING INFORMATION SERIES TASMANIAN GEOLOGICAL SURVEY MAP 20A − SIMPLIFIED GEOLOGY AND AREAS OF HIGHEST MINERAL RESOURCES TASMANIA Tasmania MINERAL EXPLORATION AND MINING POTENTIAL ENERGY and RESOURCES DEPARTMENT of INFRASTRUCTURE Judbury Opossum Blackmans Bay Bay Blackmans Bay Ranelagh PETER MURRELL NORTH HUON Allens STATE RESERVE CAPE CONTRARIETY WEST Rivulet PRIVATE SANCTUARY HEAD Kaoota CAPE Saltwater CONTRARIETY VER South River Glen Huon RI HUONVILLE Nierinna Howden TINDERBOX Margate NATURE Arm RESERVE Baretta Cape CAPE DIRECTION GHWAY Pelverata North Deliverance HI PRIVATE SANCTUARY Betsey Piersons Pt CAPE Island Electrona West Tinderbox DIRECTION BETSEY ISLAND TINDERBOX MARINE NATURE RESERVE Bay NATURE RESERVE Snug Dennes Pt TIERS Woodstock Snug Bay Dennes G Point CAPE DE LA SORTIE Upper Woodstock SNU OUTER Conningham UON Lower NORTH H Snug HEAD Franklin GREY MTN K HUONVALLEY I Killora N GBO Roaring Beach DENNES Bay ROU HILL Oyster South NATURE GH Cove Franklin RESERVE Cradoc Oyster ABORIGINAL LAND WEDGE − OYSTER COVE Cove Barnes Bay BAY QUARANTINE STATION The Yellow Kettering STATE RESERVE Bluff CHA Kettering Pt Castle NNEL Forbes Barnes Bay Wedge Bay Island Glaziers Bay ROAD Roberts Pt STORM Port Apollo Huon Cygnet Nicholls Bay Rivulet Woodbridge BRUNY Trumpeter Two Island Lower Bay Geeveston Wattle Grove Bay ISLAND BAY Wattle TASMAN Grove Birchs NATIONAL HWY Bay PARK Gardners Bay Bay y CHANNEL r Adams ona issi Bay M Curio Petcheys Bay Cairns Bay IN Bay Great MA ET MT GREEN ISLAND N Variety Waterloo Lymington CYGNET NATURE RESERVE Bay Bay HUON Bay CYG Salters Pt Variety Pt Waterloo HWY PORT Chuckle Surges Bay Head DIVIDE TONGATABU Middleton RIVER BRUNY ISLAND NECK GAME RESERVE Glendevie Simpsons Garden Island Point Creek LAND Police Pt IS Garden Is. -

The Vegetation and Flora of Three Hummock Island, Western Bass Strait

Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania, Volume 131, 1997 37 THE VEGETATION AND FLORA OF THREE HUMMOCK ISLAND, WESTERN BASS STRAIT by Stephen Harris and Jayne Balmer (with one table, four text-figures, nine plates and an appendix) HARRIS, S. & BALMER, ]., 1997 (31 :viii): The vegetation and flora of Three Hummock Island, western Bass Strait. Pap. Proc. R. Soc. Tasm. 131: 37-56. ISSN 0800-4703. Parks and Wildlife Service, Department of Environment and Land Management, GPO Box 44A, Hobart, Tasmania, Australia 7001. A survey of the vegetation of Three Hummock Island Nature Reserve recorded 289 vascular higher plant species, 60 of which were introduced. Of the native flora, six are classified as rare or vulnerable. Clarke Island, at a similar latitude in Eastern Bass Strait, has a significantly richer flora, including an element of Mainland Australian/Bassian flora for which the island is the southernmost limit. In contrast, there are no species known from Three Hummock Island that do not occur on mainland Tasmania. The greater length of time during which the land bridge at the eastern end of Bass Strait was exposed is, therefore, reflected in the flora. Three Hummock Island was cut off for a much longer period with no land connections to the north, therefore has a more insular Tasmanian flora. Climatic differences may have exacerbated the contrast. Nine vegetation mapping communities are defined, the largest proportion of the island being covered by Myrtaceae-dominated scrub. The main changes in the vegetation since the time of European discovery have been the clearing of much of the relatively fertile calcareous sands for grazing and the consequent loss of most of the Eucalyptus viminalis forests, an increased fire frequency and the introduction of exotic plants. -

The Fisher Island Field Stat Ion-With an Account of Its Principal Fauna and Flora

PAPEHS AND .PROCEEDINGS tW 'THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF TASMANIA, V'OLl.lME 92 THE FISHER ISLAND FIELD STAT ION-WITH AN ACCOUNT OF ITS PRINCIPAL FAUNA AND FLORA By E. R. GUILER, D. L. SERVENTY AND J. H. WILLIS (WITH 2 PLATES AND 9 TEXT FTGURESj t GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF FISHER ISLAND AND ITS MUTTON~BIRD ROOKERIES * INTRODUCTION mately 0'75 acres. The shoreline measures about Fisher Island Oat. 40° 10' S., long. 148° 16' E.) 530 yards and the greatest length, from North is among the smallest of the archipelago of islands Point to South Point, is 150 yards. Its elevation is comprising the Furneaux Group in eastern Bass about 19 feet above spring high-water mark. Strait. It lies off the southern shoreline of the Like the other islands in the Furneaux Group, major island in the group, Flinders Island, in Fisher Island is part of the basement Devonian Adelaide Bay, a portion of Franklin Sound which granite which forms the hills and mountain ridges separates Flinders Island from Cape Barren Island in the archipelago. On Flinders Island the low (fig. 1). Its convenient location to Lady Barron lying plains are covered by Tertiary alluvium and (the main port of Flinders Island, about 220 yards sands, with calcareous deposits in restricted areas. distant), its proximity to important commercial Limited Siluro-Devonian quartzites and slates also mutton-birding islands and the presence of a small, occur, and in the northern part of Adelaide Bay, at easily handled nesting colony of mutton-birds Petrifaction Bay, are exposures of Tertiary vesicu (PufJinus tenuirostris (Temminck), made it the lar basalts. -

ACE Export Manifest

CBP Export Manifest Appendix O - Schedule K February 2018 CBP Export Manifest Schedule K Appendix O This appendix provides a complete listing of foreign port codes in Alphabetical order by country. Foreign Port Codes Code Ports by Country Albania 48100 All Other Albania Ports 48109 Durazzo 48109 Durres 48100 San Giovanni di Medua 48100 Shengjin 48100 Skele e Vlores 48100 Vallona 48100 Vlore 48100 Volore Algeria 72101 Alger 72101 Algiers 72100 All Other Algeria Ports 72123 Annaba 72105 Arzew 72105 Arziw 72107 Bejaia 72123 Beni Saf 72105 Bethioua 72123 Bona 72123 Bone 72100 Cherchell 72100 Collo 72100 Dellys 72100 Djidjelli 72101 El Djazair 72142 Ghazaouet 72142 Ghazawet 72100 Jijel 72100 Mers El Kebir 72100 Mestghanem 72100 Mostaganem 72142 Nemours 72179 Oran Schedule K Appendix O F-1 CBP Export Manifest 72189 Skikda 72100 Tenes 72179 Wahran American Samoa 95101 Pago Pago Harbor Angola 76299 All Other Angola Ports 76299 Ambriz 76299 Benguela 76231 Cabinda 76299 Cuio 76274 Lobito 76288 Lombo 76288 Lombo Terminal 76278 Luanda 76282 Malongo Oil Terminal 76279 Namibe 76299 Novo Redondo 76283 Palanca Terminal 76288 Port Lombo 76299 Porto Alexandre 76299 Porto Amboim 76281 Soyo Oil Terminal 76281 Soyo-Quinfuquena term. 76284 Takula 76284 Takula Terminal 76299 Tombua Anguilla 24821 Anguilla 24823 Sombrero Island Antigua 24831 Parham Harbour, Antigua 24831 St. John's, Antigua Argentina 35700 Acevedo 35700 All Other Argentina Ports 35710 Bagual 35701 Bahia Blanca 35705 Buenos Aires 35703 Caleta Cordova 35703 Caleta Olivares 35703 Caleta Olivia 35711 Campana 35702 Comodoro Rivadavia 35700 Concepcion del Uruguay 35700 Diamante 35700 Ibicuy Schedule K Appendix O F-2 CBP Export Manifest 35737 La Plata 35740 Madryn 35739 Mar del Plata 35741 Necochea 35779 Pto. -

South Bruny National Park, Management Plan

South Bruny National Park, Waterfall Creek State Reserve, Green Island Nature Reserve Management Plan 2000 Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment South Bruny National Park, Waterfall Creek State Reserve, Green Island Nature Reserve Management Plan 2000 Parks and Wildlife Service Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment South Bruny National Park, Waterfall Creek State Reserve, and Green Island Nature Reserve - Management Plan 2000 SOUTH BRUNY NATIONAL PARK WATERFALL CREEK STATE RESERVE GREEN ISLAND NATURE RESERVE MANAGEMENT PLAN 2000 This management plan for the South Bruny National Park, the Waterfall Creek State Reserve and the Green Island Nature Reserve has been prepared in accordance with the requirements of Part IV of the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1970. A draft of this plan was released for public comment from 2 October 1999 to 26 November 1999. Unless otherwise specified, this plan adopts the interpretation of terms given in Section 3 of the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1970. The term “Minister” when used in the plan means the Minister administering the Act. The term “Park” refers to the South Bruny National Park. The term "Reserve" refers to the Waterfall Creek State Reserve or the Green Island Nature Reserve depending upon the context. In accordance with Section 23(1)(a) of the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1970, the managing authority for the Park and the Reserves, in this case the Director of National Parks and Wildlife, is to manage them in accordance with this management plan. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many people have assisted in the preparation of this plan by providing information and comments on earlier drafts.