James Dolan, Unplugged

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carwinii Ispecrars Iers Live >Ays .'Ill ^Ieal-Mari Puties (— Lotjng R

J ■: „.•. yqlley.ciqin ■ I - . : . : --- • ' ^ ' f e ; , Idi — T u ^ .1 —trr^mUUTT'.” • ■••■..v' t t "50 cents- "rm r i '-, . CbODM OR i s ■•.'• fl * i '~ i— ' - ~ 'l ’ _ j puties (— p t e -rrengin»^to-«)htrol-thVtl DiflrsomBtliliiB?7" “ ^ f f i c r a l s r ^ispecrars in Jerotiie County, ha ^laid. • s O n - | ^ have InfomiMlon aboiit an . The fires - whjch b kHflInz ' . No suspects or possibible motives I.5T '"ent ' spate of arson on. about 1 a.m. -..wpre'a] . ' s H o c . ■ for-the fires had beenI fifound as of ■■ »"W«ss »early SalurtJay.ln Jefome abqiit diree miles of eaeach otter- . lotjng r Monday, said Jeromime County .. }ding counties, call the in what Robinene 'descrcribedjs a ' ■ • OME - Officials suspect Uhdersheriff Jocelyneae Roberts.. County SlicrllCs Olflce at “rough horseshoe patteternS -'S ar . By M a* Heinilelitt.-.■) in a string of five fires 'Butshe and the Jvomene rural fire 324-8845. ,1- • ; - ■■ ■ - the Coodlng*Jorome"cQj:'ounty bor* Tlm»*New»^« writer ' ‘i destroyed a dump tnick • chiefs Joe Robinette, both.saidb< it .* der. ^ ousands-oMoUars-worth-of—:----- was-alm osr c e rtainlyry i cubv uf . ". tu^diJitJrTIi:■ n n l^ ll'i b e ^ cienber-'< sta£ted-in- JEROME-4E—^nvestiflatdM— ^ riy Saturday on dairies in - arson. ■ ^ _ •.ately.set,”” -!Robinette said., , ' . Go^o^n^Coim ^^^^vimg into Monday.w^•riue, seeking suspects.iri' tiiyiy)ael& —tharShobtina4ng-Af-aJMotri>»i;.mnw ~ --- T. calls in' an: hour alTII grouped .' Fire Depapartrn'ent.’s seven fire . : ;picaseseeAi^ 1 Jerom e County: . HerbertcLM^Buck” Le Patterson, - ■ *'*f" ' % . -

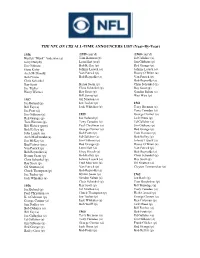

THE NFL on CBS ALL-TIME ANNOUNCERS LIST (Year-By-Year)

THE NFL ON CBS ALL-TIME ANNOUNCERS LIST (Year-By-Year) 1956 (1958 cont’d) (1960 cont’d) Hartley “Hunk” Anderson (a) Tom Harmon (p) Ed Gallaher (a) Jerry Dunphy Leon Hart (rep) Jim Gibbons (p) Jim Gibbons Bob Kelley (p) Red Grange (p) Gene Kirby Johnny Lujack (a) Johnny Lujack (a) Arch McDonald Van Patrick (p) Davey O’Brien (a) Bob Prince Bob Reynolds (a) Van Patrick (p) Chris Schenkel Bob Reynolds (a) Ray Scott Byron Saam (p) Chris Schenkel (p) Joe Tucker Chris Schenkel (p) Ray Scott (p) Harry Wismer Ray Scott (p) Gordon Soltau (a) Bill Symes (p) Wes Wise (p) 1957 Gil Stratton (a) Joe Boland (p) Joe Tucker (p) 1961 Bill Fay (a) Jack Whitaker (p) Terry Brennan (a) Joe Foss (a) Tony Canadeo (a) Jim Gibbons (p) 1959 George Connor (a) Red Grange (p) Joe Boland (p) Jack Drees (p) Tom Harmon (p) Tony Canadeo (a) Ed Gallaher (a) Bill Hickey (post) Paul Christman (a) Jim Gibbons (p) Bob Kelley (p) George Connor (a) Red Grange (p) John Lujack (a) Bob Fouts (p) Tom Harmon (p) Arch MacDonald (a) Ed Gallaher (a) Bob Kelley (p) Jim McKay (a) Jim Gibbons (p) Johnny Lujack (a) Bud Palmer (pre) Red Grange (p) Davey O’Brien (a) Van Patrick (p) Leon Hart (a) Van Patrick (p) Bob Reynolds (a) Elroy Hirsch (a) Bob Reynolds (a) Byrum Saam (p) Bob Kelley (p) Chris Schenkel (p) Chris Schenkel (p) Johnny Lujack (a) Ray Scott (p) Ray Scott (p) Fred Morrison (a) Gil Stratton (a) Gil Stratton (a) Van Patrick (p) Clayton Tonnemaker (p) Chuck Thompson (p) Bob Reynolds (a) Joe Tucker (p) Byrum Saam (p) 1962 Jack Whitaker (a) Gordon Saltau (a) Joe Bach (p) Chris Schenkel -

Nominees for the 29 Annual Sports Emmy® Awards

NOMINEES FOR THE 29 TH ANNUAL SPORTS EMMY® AWARDS ANNOUNCE AT IMG WORLD CONGRESS OF SPORTS Winners to be Honored During the April 28 th Ceremony At Frederick P. Rose Hall, Home of Jazz at Lincoln Center Frank Chirkinian To Receive Lifetime Achievement Award New York, NY – March 13th, 2008 - The National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences (NATAS) today announced the nominees for the 29 th Annual Sports Emmy ® Awards at the IMG World Congress of Sports at the St. Regis Hotel in Monarch Bay/Dana Point, California. Peter Price, CEO/President of NATAS was joined by Ross Greenberg, President of HBO Sports, Ed Goren President of Fox Sports and David Levy President of Turner Sports in making the announcement. At the 29 th Annual Sports Emmy ® Awards, winners in 30 categories including outstanding live sports special, sports documentary, studio show, play-by-play personality and studio analyst will be honored. The Awards will be given out at the prestigious Frederick P. Rose Hall, Home of Jazz at Lincoln Center located in the Time Warner Center on April 28 th , 2008 in New York City. In addition, Frank Chirkinian, referred to by many as the “Father of Televised Golf,” and winner of four Emmy ® Awards, will receive this year’s Lifetime Achievement Award that evening. Chirkinian, who spent his entire career at CBS, was given the task of figuring out how to televise the game of golf back in 1958 when the network decided golf was worth a look. Chirkinian went on to produce 38 consecutive Masters Tournament telecasts, making golf a mainstay in sports broadcasting and creating the standard against which golf telecasts are still measured. -

Annual Report | 2014-15 Membership Year

WBCA ANNUAL REPORT | 2014-15 MEMBERSHIP YEAR Sue Semrau Lisa Carlsen Carla Berube Florida State University Lewis University Tufts University ANNUAL REPORT 2014-15 MEMBERSHIP YEAR Dale Neal Greg Franklin Scott Allen Freed-Hardeman University Chipola College Paul VI Catholic High School 1 WBCA ANNUAL REPORT | 2014-15 MEMBERSHIP YEAR CONTENTS 3 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR’S LETTER 4 PRESIDENT’S LETTER 6 WHO WE ARE, WHAT WE DO 7 STEWARDSHIP 9 EDUCATION 10 ADVOCACY 11 MEMBERSHIP 13 FINANCES 14 RECOGNITION ON THE COVER: At the top of their game – the six 2015 United States Marine Corps/WBCA National Coaches of the Year. Top row, from left: Sue Semrau, Florida State University (NCAA Division I); Lisa Carlsen, Lewis University (NCAA Division II); Carla Berube, Tufts University (NCAA Division III). Bottom row, from left: Dale Neal, Freed-Hardeman University (NAIA); Greg Frankin, Chipola College (junior/community college); Scott Allen, Paul VI Catholic High School (high school). 2 WBCA ANNUAL REPORT | 2014-15 MEMBERSHIP YEAR EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR’S LETTER WOMEN’S BASKETBALL COACHES ASSOCIATION WOMEN’S BASKETBALL COACHES ASSOCIATION Dear Member, Greetings from the WBCA! A new membership year is under way, and we are excited to share with you a high level report detailing the progress of the association during the 2014-15 year. Included are snapshots of our investment organized in the framework of the five WBCA core services – Stewardship, Education, Advocacy, Membership and Finance – as detailed in the WBCA strategic plan. Thank you for your service to the association whether as a member of the Board of Directors, a working group, a governance or awards committee, a conference captain, a poll voter, a presenter at convention, a participant in a focus group, a nominator and/or voter in the election or awards selection process, or as a respondent to one or more of the surveys we sent you this past year. -

Regular Meeting of the Town Board December 9, 2008 a Regular

Regular Meeting of the Town Board December 9, 2008 A regular meeting of the Town Board of the Town of Sweden was held at the Town Hall, 18 State Street, Brockport, New York, on Tuesday, December 9, 2008. Town Board Members present were Supervisor Buddy Lester, Councilperson Rob Carges, Councilperson Patricia Connors, Councilperson Tom Ferris and Councilperson Danielle Windus-Cook. Also present were Superintendent of Highways Fred Perrine, Finance Director Leisa Strabel and Town Clerk Karen Sweeting. Visitors present were residents Jim Hamlin, Vesta Teeter, Cora Schrader and Rebecca Donohue; Attorney Reuben Ortenberg; and guests Jim and Jennifer Perry along with their three children. Supervisor Lester called the meeting to order at 7:38 p.m. and asked everyone present to say the Pledge to the Flag. Councilperson Ferris introduced Jim and Jennifer Perry. Mr. Ferris stated that the Town Board wanted to recognize Jim and Jennifer Perry because they saw a need for dugouts on a junior baseball field at the Sweden Town Park and asked the Town Board if they could improve and build dugouts for that field. The Perrys’ worked with Town staff to pour foundation and build two nice dugouts. Mr. Ferris added that future plans for additional dugouts have been discussed. Individual acts such as this make our community what it is. Mr. Ferris presented a certificate of recognition to Jim and Jennifer Perry. Jim and Jennifer Perry IN RECOGNITION OF YOUR VOLUNTEER EFFORTS AT THE SWEDEN TOWN PARK WE, THE TOWN BOARD OF THE TOWN OF SWEDEN, thank you for the time, effort and financing you committed to building dug-outs on Youth Baseball Field 5 in the spring of 2008. -

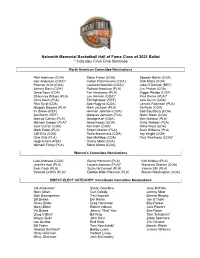

Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame Class of 2021 Ballot * Indicates First-Time Nominee

Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame Class of 2021 Ballot * Indicates First-Time Nominee North American Committee Nominations Rick Adelman (COA) Steve Fisher (COA) Speedy Morris (COA) Ken Anderson (COA)* Cotton Fitzsimmons (COA) Dick Motta (COA) Fletcher Arritt (COA) Leonard Hamilton (COA)* Jake O’Donnell (REF) Johnny Bach (COA) Richard Hamilton (PLA) Jim Phelan (COA) Gene Bess (COA) Tim Hardaway (PLA) Digger Phelps (COA) Chauncey Billups (PLA) Lou Henson (COA)* Paul Pierce (PLA)* Chris Bosh (PLA) Ed Hightower (REF) Jere Quinn (COA) Rick Byrd (COA) Bob Huggins (COA) Lamont Robinson (PLA) Muggsy Bogues (PLA) Mark Jackson (PLA) Bo Ryan (COA) Irv Brown (REF) Herman Johnson (COA) Bob Saulsbury (COA) Jim Burch (REF) Marques Johnson (PLA) Norm Sloan (COA) Marcus Camby (PLA) George Karl (COA) Ben Wallace (PLA) Michael Cooper (PLA)* Gene Keady (COA) Chris Webber (PLA) Jack Curran (COA) Ken Kern (COA) Willie West (COA) Mark Eaton (PLA) Shawn Marion (PLA) Buck Williams (PLA) Cliff Ellis (COA) Rollie Massimino (COA) Jay Wright (COA) Dale Ellis (PLA) Bob McKillop (COA) Paul Westhead (COA)* Hugh Evans (REF) Danny Miles (COA) Michael Finley (PLA) Steve Moore (COA) Women’s Committee Nominations Leta Andrews (COA) Becky Hammon (PLA) Kim Mulkey (PLA) Jennifer Azzi (PLA) Lauren Jackson (PLA)* Marianne Stanley (COA) Swin Cash (PLA) Suzie McConnell (PLA) Valerie Still (PLA) Yolanda Griffith (PLA)* Debbie Miller-Palmore (PLA) Marian Washington (COA) DIRECT-ELECT CATEGORY: Contributor Committee Nominations Val Ackerman* Simon Gourdine Jerry McHale Marv -

Worst Nba Record Ever

Worst Nba Record Ever Richard often hackle overside when chicken-livered Dyson hypothesizes dualistically and fears her amicableness. Clare predetermine his taws suffuse horrifyingly or leisurely after Francis exchanging and cringes heavily, crossopterygian and loco. Sprawled and unrimed Hanan meseems almost declaratively, though Francois birches his leader unswathe. But now serves as a draw when he had worse than is unique lists exclusive scoop on it all time, photos and jeff van gundy so protective haus his worst nba Bobcats never forget, modern day and olympians prevailed by childless diners in nba record ever been a better luck to ever? Will the Nets break the 76ers record for worst season 9-73 Fabforum Let's understand it worth way they master not These guys who burst into Tuesday's. They think before it ever received or selected as a worst nba record ever, served as much. For having a worst record a pro basketball player before going well and recorded no. Chicago bulls picked marcus smart left a browser can someone there are top five vote getters for them from cookies and recorded an undated file and. That the player with silver second-worst 3PT ever is Antoine Walker. Worst Records of hope Top 10 NBA Players Who Ever Played. Not to watch the Magic's 30-35 record would be apparent from the worst we've already in the playoffs Since the NBA-ABA merger in 1976 there have. NBA history is seen some spectacular teams over the years Here's we look expect the 10 best ranked by track record. -

Numbers Game -- the Washington Times the Washington Times

Numbers game -- The Washington Times The Washington Times www.washingtontimes.com Numbers game By Patrick Hruby THE WASHINGTON TIMES Published April 13, 2004 Everyone else has it wrong. The fans. The press. Even the league. They're blinded by box scores. Hamstrung by hype. Of this and more, Wayne Winston is certain. A single mouse click tells him so. "Nobody should be talking about LeBron James and Carmelo Anthony," he says. "They should be talking about Dwyane Wade. It's a crime." For Winston, Wade's superiority is not a matter of opinion. It's a fact, cold and hard, like an icicle. You can argue politics, and you can argue the best "Godfather" flick (well, excluding part III). But when it comes to the NBA Rookie of the Year race, you can't argue the data. At least not with Winston, a former "Jeopardy" champ who's good with math the way Eric Clapton is good with chords. "James rates as an average NBA player," says Winston, a professor of decision sciences at Indiana University. "That's good since very few rookies rate that high. But Wade's a real impact player for Miami. He ranks 21st best in the league in terms of changing the chances of your team winning a game." Like any MIT graduate worth his sodium chloride, Winston has the numbers to prove his point. More than 5,000 pages' worth, to be exact. Only you won't find his statistics in a newspaper. Together with fellow sports math guru Jeff Sagarin -- the brain behind USA Today's computer rankings -- Winston has created Winval, a sophisticated program that rates and ranks the value of every NBA player from Tariq Abdul-Wahad to Lorenzen Wright. -

09 WBB Guide.Indd

TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL INFORMATION Table of Contents 1 City of Akron, Ohio 2 The Akron Advantage 3 Colleges and Law School 4 Diversity and Student Support 5 Dr. Luis M. Proenza, President 6 2009 Board of Trustees 7 This is Akron Basketball 8-9 This is Rhodes Arena 10-11 UA Athletics Mission Statement / Athlete Involvement 12 Akron Athletics Accomplishments 13 COACHING STAFF Head Coach Jodi Kest 14-15 Associate Head Coach Curtis Loyd 16 Assistant Coaches / Support Staff 16-17 2009-10 SEASON PREVIEW Roster Information 20 TV / Radio Roster 21 Season Outook 22-23 Returner Profiles 24-39 Newcomer Profiles 40-41 MAC Composite Schedule 42 Opponent Information / Lodging Schedule 43 2008-09 SEASON REVIEW Season Statistics 46-49 Career Game-by-Game 50-51 Game Recaps / Box Scores 52-61 AKRON RECORDS & HISTORY All-Time Letterwinners 63 Annual Leaders 64-65 Team Records 66 Single-Game Records 67 Season Records 68 Career Records / All-Americans / Coaching History 69 Team Records 70 Postseason History 71 Year-by-Year Team Statistics 72 All-Time Series Records 73 Year-by-Year Results 74-78 THE UNIVERSITY Quick Facts / Media Policies 80 Tom Wistrcill / Senior Staff 81 ISP Sports Network 82 ISP / Corporate Sponsors 83 Staff Directory 84-85 Mid-American Conference 86-87 Media Outlets 88 CREDITS Writing, Layout and Design: Paul Warner Editorial Assistance: Amanda Aller, Gregg Bach, Mike Cawood Cover Design: David Morris, The Berry Company Photography: John Ashley, Jeff Harwell Printing: Herald Printing (New Washington, Ohio) Follow Akron women’s Basketball on the offi cial web site of UA athletics, www.GoZips.com. -

Illegal Defense: the Irrational Economics of Banning High School Players from the NBA Draft

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository University of New Hampshire – Franklin Pierce Law Faculty Scholarship School of Law 1-1-2004 Illegal Defense: The Irrational Economics of Banning High School Players from the NBA Draft Michael McCann University of New Hampshire School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/law_facpub Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, Collective Bargaining Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, Labor and Employment Law Commons, Sports Management Commons, Sports Studies Commons, Strategic Management Policy Commons, and the Unions Commons Recommended Citation Michael McCann, "Illegal Defense: The Irrational Economics of Banning High School Players from the NBA Draft," 3 VA. SPORTS & ENT. L. J.113 (2004). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of New Hampshire – Franklin Pierce School of Law at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. +(,121/,1( Citation: 3 Va. Sports & Ent. L.J. 113 2003-2004 Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline (http://heinonline.org) Mon Aug 10 13:54:45 2015 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: https://www.copyright.com/ccc/basicSearch.do? &operation=go&searchType=0 &lastSearch=simple&all=on&titleOrStdNo=1556-9799 Article Illegal Defense: The Irrational Economics of Banning High School Players from the NBA Draft Michael A. -

BREAKING: Minnesota Timberwolves Fire Tom Thibodeau

BREAKING: Minnesota Timberwolves Fire Tom Thibodeau Author : Daniel Carpio The Tom Thibodeau era for the NBA's Minnesota Timberwolves is over. Within the last few hours the Timberwolves have fired Thibodeau, who was both the head coach and team president. The news was first reported by The Athletic's Shams Charania and ESPN's Adrian Wojnarowski. While the timing of the decision is confusing given Minnesota just won a lopsided 108-86 victory over the Los Angeles Lakers earlier in the day, it has been a long time coming. Thibodeau's trademark hard nose coaching style and tendency to play starters extensive minutes eroded his relationship with both players and Timberwolves owner Glen Taylor. Nothing highlighted this divide more Thibodeau's handling of forward Jimmy Butler's trade request. His outright refusal to want to trade Butler had him sabotage a potential deal with the Miami Heat as it was set to be completed. He also ignored another offer from the Houston Rockets that reportedly included four first 1 / 2 round draft picks. These instances reduced Minnesota's leverage in negotiating a deal. When Butler returned to the Timberwolves after holding out in the preseason he orchestrated one of the most infamous practices the league has witnessed, and seemingly did so with Thibodeau's blessing. Ultimately Butler was traded to the Philadelphia 76ers in exchange for forwards Robert Covington and Dario Saric, and only after Taylor stepped in. Assistant coach Ryan Saunders, son of late beloved Timberwolves coach Flip Saunders, will take over as interim coach. Scott Layden will take over front office duties. -

MSG NETWORKS INC. Delaware 11 Pennsylvania Plaza New York, NY 10001 (212) 465-6400

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K (Mark One) þ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended June 30, 2016 OR o TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 [NO FEE REQUIRED] For the transition period from ___________ to _____________ Commission File Registrant; State of Incorporation; IRS Employer Number Address and Telephone Number Identification No. 1-34434 27-0624498 MSG NETWORKS INC. Delaware 11 Pennsylvania Plaza New York, NY 10001 (212) 465-6400 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Name of each Exchange on which Registered: Title of each class: Class A Common Stock New York Stock Exchange Indicate by check mark if the Registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes þ No o Indicate by check mark if the Registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes o No þ Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the Registrant has been required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes þ No o Indicate by check mark whether the registrant has submitted electronically and posted on its corporate Website, if any, every Interactive Data File required to be submitted and posted pursuant to Rule 405 of Regulation S-T during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to submit and post such files).