Second Place Social Sciences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Opening Remarks by Senior Minister Teo Chee Hean at the Public Sector Data Security Review Committee Press Conference on 27 November 2019

OPENING REMARKS BY SENIOR MINISTER TEO CHEE HEAN AT THE PUBLIC SECTOR DATA SECURITY REVIEW COMMITTEE PRESS CONFERENCE ON 27 NOVEMBER 2019 Good morning everyone and thank you for attending the press conference. Work of the PSDSRC 2 As you know, in 2018 and 2019, we uncovered a number of data-related incidents in the public sector. In response to these incidents, the government had immediately introduced additional IT security measures. Some of these measures included network traffic and database activity monitoring, and endpoint detection and response for all critical information infrastructure. But, there was a need for a more comprehensive look at public sector data security. 3 On 31 March this year, the Prime Minister directed that I chair a Committee to conduct a comprehensive review of data security policies and practices across the public sector. 4 I therefore convened a Committee, which consisted of my colleagues from government - Dr Vivian Balakrishnan, Mr S Iswaran, Mr Chan Chun Sing, and Dr Janil Puthucheary - as well as five international and private sector representatives with expertise in data security and technology. If I may just provide the background of these five private sector members: We have Professor Anthony Finkelstein, Chief Scientific Adviser for National Security to the UK Government and an expert in the area of data and cyber security; We have Mr David Gledhill who is with us today. He is the former Chief Information Officer of DBS and has a lot of experience in applying these measures in the financial and banking sector; We have Mr Ho Wah Lee, a former KPMG partner with 30 years of experience in information security, auditing and related issues across a whole range of entities in the private and public sector; We have Mr Lee Fook Sun, who is the Executive Chairman of Ensign Infosecurity. -

Merdeka Generation Package $100 Top-Up Benefit

Merdeka Generation Package $100 Top-Up Benefit The Merdeka Generation (MG) One-Time $100 Top-Up will be available from 01 July 2019 onwards. Apart from the top-up locations at the MRT stations and bus interchanges, temporary top-up booths at selected Community Clubs/ Centres will be set up to provide even greater convenience to our MGs with their top ups. a) TransitLink Ticket Offices Operating Hours TransitLink Ticket Offices Public Location Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Holidays 1 Aljunied MRT Station * 1200 - 1930 Closed 2 Ang Mo Kio MRT Station 0800 - 2100 3 Bayfront MRT Station (CCL)* Closed 1200 - 2000 4 Bedok Bus Interchange 1000 - 2000 1000 - 1700 Closed 5 Bedok MRT Station * 1200 - 2000 6 Bishan MRT Station * 1200 - 1930 Closed 7 Boon Lay Bus Interchange 0800 - 2100 8 Bugis MRT Station 1000 - 2100 9 Bukit Batok MRT Station * 1200 - 1930 10 Bukit Merah Bus Interchange * 1200 - 1930 11 Changi Airport MRT Station ~ 0800 - 2100 12 Chinatown MRT Station ~@ 0800 - 2100 13 City Hall MRT Station 0900 - 2100 14 Clementi MRT Station 0800 - 2100 15 Eunos MRT Station * 1200 - 1930 1200 - 1800 Closed 16 Farrer Park MRT Station * 1200 - 1930 17 HarbourFront MRT Station ~ 0800 - 2100 Updated as of 2 July 2019 Operating Hours TransitLink Ticket Offices Public Location Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Holidays 18 Hougang MRT Station * 1200 - 1930 19 Jurong East MRT Station * 1200 - 1930 20 Kranji MRT Station * 1230 - 1930 # 1230 - 1930 ## Closed## 21 Lakeside MRT Station * 1200 - 1930 22 Lavender MRT Station * 1200 - 1930 Closed 23 Novena MRT Station -

Why the Changes, and Why Now?

Why the changes, and why now? The upcoming Cabinet reshufe on May 15 comes earlier in the Government’s term than normal, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong said yesterday. Below are his explanations for the various movements. On Mr Heng Swee Keat relinquishing Finance: On moving Mr Chan Chun Sing from As I announced two weeks Relinquishing Finance will Trade and Industry to Education: ago, Heng Swee Keat will free him to concentrate continue as Deputy Prime more on the Chun Sing has done an excellent job Minister and Coordinating whole-of-government getting our economy back on track, and Minister for Economic economic agenda, including preparing our industries and Policies. He will also chairing the Future companies to respond to structural continue to oversee the Economy Council, and changes in the global economy. This Strategy Group within the incorporating the has been a major national priority. Now Prime Minister’s Ofce, recommendations of the I am sending him to Education, where which coordinates our Emerging Stronger he will build on the work of previous policies and plans across Taskforce into the work of education ministers, to improve our the Government, as well as the council. He will also education system to bring out the best the National Research continue to co-chair the in every child and student, and develop Foundation. As Finance Joint Council for Bilateral young Singaporeans for the future. Minister, Swee Keat has Cooperation (JCBC), Nurturing people is quite different from carried a heavy burden, together with PRC (People’s growing the economy or mobilising especially during Covid-19 Republic of China) unions. -

PRESS RELEASE First Meeting of National Jobs Council 1. As

PRESS RELEASE First Meeting of National Jobs Council 1. As announced by Deputy Prime Minister Heng Swee Keat in the Fortitude Budget, the National Jobs Council has been formed to identify and develop job opportunities and skills training for Singaporeans amidst the COVID-19 situation. Chaired by Senior Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam, the Council will mobilise the tripartite partners’ networks and schemes to maximise support for jobseekers. The Council will include other political office holders and leaders from industry and unions, with Deputy Prime Minister Heng Swee Keat as Advisor. (Please refer to the Annex for the list of Council members.) The National Jobs Council will also align its work and implementation strategies with that of the Future Economy Council and the Emerging Stronger Taskforce. 2. The Council met for the first time today. It took account of the impact of COVID- 19 on the outlook for jobs, and discussed priority areas for achieving the SGUnited Jobs and Skills Package. The Council confirmed the following Terms of Reference: a. Identify and develop job opportunities for Singaporeans amidst COVID-19 and its aftermath; b. Rally and mobilise tripartite partners and training providers to establish a sizeable bank of SGUnited Jobs and Skills opportunities, catering to various sectors and every skill level; and c. Enable Singaporeans to take full advantage of the scaled-up opportunities, through tight coordination across Government and tripartite partners and effective implementation of: i. Job creation and matching; ii. Attachments and training for re-skilling; and iii. Job redesign in support of enterprise transformation. 3. The Council will oversee the design and implementation of the SGUnited Jobs and Skills Package announced in the Fortitude Budget. -

Forging Ahead

FY2019 Annual Report FORGING AHEAD DELIVERING WORLD-CLASS PRIMARY CARE FORGING AHEAD The National Healthcare Group Polyclinics’ (NHGP) Annual Report FY2019, titled ‘Forging Ahead’, showcases our journey in delivering quality primary care. To provide care that is world-class, we must be prepared to challenge old ideas and break new ground. The paper-cutting imagery on the cover and throughout the Annual Report depicts how NHGP has navigated through the intricacies and complexities of primary healthcare, forged ahead in the face of challenges, and found breakthroughs as part of this journey. On the cover, the burst of colours and the blooming petals portray the collaborative synergy of our staff and partners as well as our constant drive to meet the growing needs of Singapore’s population. This journey of constant growth and discovery has made NHGP a leader in advancing Family Medicine and transforming primary healthcare for the benefit of all Singaporeans. CONTENTS OUR VISION To be the leading health-promoting institution that helps advance Family Medicine and transform 04 06 08 primary healthcare in Singapore. GROUP CEO’S MESSAGE CEO’S MESSAGE NHGP SENIOR MANAGEMENT OUR MISSION We will improve health and reduce illness through 10 18 24 patient-centred quality primary healthcare that is accessible, seamless, comprehensive, appropriate and cost-effective in an CHAPTER 1 CHAPTER 2 CHAPTER 3 environment of continuous learning and relevant research. Combatting a Developing Population Charting Our Way Global Pandemic Health Forward OUR VALUES 32 36 People-Centredness Compassion CHAPTER 4 CHAPTER 5 We value diversity, respect each other We care with love, humility Advancing Towards a Enhancing Our and encourage joy in work. -

853M Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

853M bus time schedule & line map 853M Upp East Coast Ter View In Website Mode The 853M bus line (Upp East Coast Ter) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Upp East Coast Ter: 5:40 AM - 11:25 PM (2) Yishun Int: 6:00 AM - 11:17 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 853M bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 853M bus arriving. Direction: Upp East Coast Ter 853M bus Time Schedule 71 stops Upp East Coast Ter Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 5:40 AM - 11:25 PM Monday Not Operational Yishun Ave 2 - Yishun Int (59009) Tuesday Not Operational Yishun Ctrl 1 - Opp Blk 932 (59669) 30A Yishun Central 1, Singapore Wednesday Not Operational Yishun Ctrl 2 - Yishun Community Hosp (59619) Thursday Not Operational 100 Yishun Central, Singapore Friday Not Operational Yishun Ave 2 - Blk 608 (59059) Saturday Not Operational 612 Yishun Street 61, Singapore Yishun Ave 2 - Opp Khatib Stn (59049) Yishun Ave 2 - Yishun Sports Hall (59039) 853M bus Info Direction: Upp East Coast Ter Lentor Ave - Aft Yishun Ave 1 (59029) Stops: 71 Trip Duration: 117 min Lentor Ave - Aft Sg Seletar Bridge (59019) Line Summary: Yishun Ave 2 - Yishun Int (59009), Yishun Ctrl 1 - Opp Blk 932 (59669), Yishun Ctrl 2 - Lentor Ave - Opp Bullion Pk Condo (55269) Yishun Community Hosp (59619), Yishun Ave 2 - Blk 608 (59059), Yishun Ave 2 - Opp Khatib Stn (59049), Lentor Ave - Opp Countryside Est (55259) Yishun Ave 2 - Yishun Sports Hall (59039), Lentor Ave - Aft Yishun Ave 1 (59029), Lentor Ave - Aft Sg Seletar Bridge (59019), Lentor Ave -

Singapore's Abc Waters

Singapore’s ABC Waters Programme 活力,美丽,清洁的新加坡水环境计划 SINGAPORE’S ABC WATERS THE BLUE MAP OF SINGAPORE 新加坡的蓝图 17 reservoirs 水库 32 rivers 河流 7,000 km of waterways and drains 公里的水路与排水 ABC WATERS PROGRAMME ABC 水域计划 Launched in 2006 2006 ACTIVE 活力的 BEAUTIFUL 美丽的 CLEAN 清洁的 New Recreational Spaces Integration of waters Improved Water Quality 新休闲空间 with urban landscape 改进水体水质 水与城市景观一体化 Typical concrete waterways 典型混凝土排水水路 Copyright © Centre for Liveable Cities Early attempts at beautifying waterbodies 美化水体的早期尝试 Sungei Api Api 阿比阿比河 Pang Sua Pond 榜耍塘 Copyright © Centre for Liveable Cities ABC WATERS PROJECTS ABC 水域项目 SUNGEI API API AND SUNGEI TAMPINES KALLANG RIVER (POTONG PASIR) – ROCHOR CANAL SUNGEI PUNGGOL Source: PUB, Singapore’s water agency ABC Waters @ Bishan Ang Mo Kio Park Before 整治前 ABC Waters @ Bishan Ang Mo Kio Park Completed 2012 整治后 2012 Integrating the design with the surroundings 设计与环 境相结合 Meditative atmosphere: Proximity to Lower serene zone Dog run, bicycle and skates Peirce Reservoir: rental in the old Bishan tranquil and quiet link Park: active recreation to the Central zone Catchment Nature Ponds in the old Reserve Bishan Park: improved and integrated with the cleansing biotope Pond Gardens River Plains 河道平原 水塘花园 Availability of space allows for the river to boldly meander into the park Source: PUB, Singapore’s water agency ABC Waters @ Kallang River – Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park Soil bioengineering techniques Rip Rap w/ Cuttings 其他植被 Gabion Wall 石笼网墙 Reed Roll 芦苇 Reed Roll 芦苇 KALLANG RIVER @ BISHAN-ANG MO KIO PARK 石笼网,植被层,木框架挡土墙 -

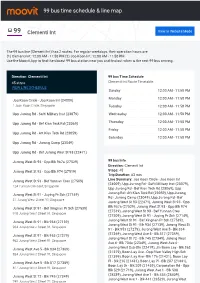

99 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

99 bus time schedule & line map 99 Clementi Int View In Website Mode The 99 bus line (Clementi Int) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Clementi Int: 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM (2) Joo Koon Int: 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 99 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 99 bus arriving. Direction: Clementi Int 99 bus Time Schedule 45 stops Clementi Int Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Monday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Joo Koon Circle - Joo Koon Int (24009) 1 Joon Koon Circle, Singapore Tuesday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Upp Jurong Rd - Safti Military Inst (23079) Wednesday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Upp Jurong Rd - Bef Kian Teck Rd (23069) Thursday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Friday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Upp Jurong Rd - Aft Kian Teck Rd (23059) Saturday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Upp Jurong Rd - Jurong Camp (23049) Upp Jurong Rd - Bef Jurong West St 93 (22471) Jurong West St 93 - Opp Blk 987a (27529) 99 bus Info Direction: Clementi Int Jurong West St 93 - Opp Blk 974 (27519) Stops: 45 Trip Duration: 63 min Jurong West St 93 - Bef Yunnan Cres (27509) Line Summary: Joo Koon Circle - Joo Koon Int (24009), Upp Jurong Rd - Safti Military Inst (23079), 124 Yunnan Crescent, Singapore Upp Jurong Rd - Bef Kian Teck Rd (23069), Upp Jurong Rd - Aft Kian Teck Rd (23059), Upp Jurong Jurong West St 91 - Juying Pr Sch (27149) Rd - Jurong Camp (23049), Upp Jurong Rd - Bef 31 Jurong West Street 91, Singapore Jurong West St 93 (22471), Jurong West St 93 - Opp Blk 987a (27529), Jurong West St 93 - Opp Blk -

Speech by Minister for Trade and Industry Chan Chun Sing in Parliament on 14 May 2018 Debate on President's Address

EMBARGOED TILL DELIVERY PLEASE CHECK AGAINST DELIVERY SPEECH BY MINISTER FOR TRADE AND INDUSTRY CHAN CHUN SING IN PARLIAMENT ON 14 MAY 2018 DEBATE ON PRESIDENT’S ADDRESS INTRODUCTION 1. Mr Speaker Sir, for 53 years, Singapore has not only survived, but thrived-in spite of. a. We lack a conventional hinterland for access to resources and markets. So we worked hard to grow our economic lifelines – connecting ourselves to the world. b. And in building a collective future for ourselves, we strived hard to unite our people of different races, languages and religions. c. There is indeed much that we can be proud of. d. However, we must never be complacent about our shared future. 2. In these times of rapid geopolitical changes, technological disruption and transition, many Singaporeans are concerned, and understandably so. Many ask simple questions: a. Can Singapore continue to thrive? b. Will there be opportunities for future generations to similarly realise their potential? c. Will we remain united, despite the many forces that threaten to pull us apart? 3. These are important questions. a. I am heartened that Singaporeans are concerned with these important issues. 4. While we must be alert and alive to these challenges, we need not be afraid. a. There will always be challenges, so too, opportunities. b. Our challenges do not define us. Our responses will. 5. Our challenges are not insurmountable. And just like the generations before us, we too can be “pioneers of our generation”. 1 EMBARGOED TILL DELIVERY PLEASE CHECK AGAINST DELIVERY a. Pioneers who will build and leave behind a stronger foundation. -

Participating Merchants

PARTICIPATING MERCHANTS PARTICIPATING POSTAL ADDRESS MERCHANTS CODE 460 ALEXANDRA ROAD, #01-17 AND #01-20 119963 53 ANG MO KIO AVENUE 3, #01-40 AMK HUB 569933 241/243 VICTORIA STREET, BUGIS VILLAGE 188030 BUKIT PANJANG PLAZA, #01-28 1 JELEBU ROAD 677743 175 BENCOOLEN STREET, #01-01 BURLINGTON SQUARE 189649 THE CENTRAL 6 EU TONG SEN STREET, #01-23 TO 26 059817 2 CHANGI BUSINESS PARK AVENUE 1, #01-05 486015 1 SENG KANG SQUARE, #B1-14/14A COMPASS ONE 545078 FAIRPRICE HUB 1 JOO KOON CIRCLE, #01-51 629117 FUCHUN COMMUNITY CLUB, #01-01 NO 1 WOODLANDS STREET 31 738581 11 BEDOK NORTH STREET 1, #01-33 469662 4 HILLVIEW RISE, #01-06 #01-07 HILLV2 667979 INCOME AT RAFFLES 16 COLLYER QUAY, #01-01/02 049318 2 JURONG EAST STREET 21, #01-51 609601 50 JURONG GATEWAY ROAD JEM, #B1-02 608549 78 AIRPORT BOULEVARD, #B2-235-236 JEWEL CHANGI AIRPORT 819666 63 JURONG WEST CENTRAL 3, #B1-54/55 JURONG POINT SHOPPING CENTRE 648331 KALLANG LEISURE PARK 5 STADIUM WALK, #01-43 397693 216 ANG MO KIO AVE 4, #01-01 569897 1 LOWER KENT RIDGE ROAD, #03-11 ONE KENT RIDGE 119082 BLK 809 FRENCH ROAD, #01-31 KITCHENER COMPLEX 200809 Burger King BLK 258 PASIR RIS STREET 21, #01-23 510258 8A MARINA BOULEVARD, #B2-03 MARINA BAY LINK MALL 018984 BLK 4 WOODLANDS STREET 12, #02-01 738623 23 SERANGOON CENTRAL NEX, #B1-30/31 556083 80 MARINE PARADE ROAD, #01-11 PARKWAY PARADE 449269 120 PASIR RIS CENTRAL, #01-11 PASIR RIS SPORTS CENTRE 519640 60 PAYA LEBAR ROAD, #01-40/41/42/43 409051 PLAZA SINGAPURA 68 ORCHARD ROAD, #B1-11 238839 33 SENGKANG WEST AVENUE, #01-09/10/11/12/13/14 THE -

Monograph-1-29-Dec-2014.Pdf

Public Housing in Singapore: Residents’ Prole, Housing Satisfaction and Preferences HDB Sample Household Survey 2013 Published by Housing & Development Board HDB Hub 480 Lorong 6 Toa Payoh Singapore 310480 Research Team Goh Li Ping (Team Leader) William Lim Teong Wee Tan Hui Fang Wu Juan Juan Tan Tze Hui Clara Wong Lee Hua Lim E-Farn Fiona Lee Yiling Esther Chua Jia Ping Sangeetha d/o Panearselvan Amy Wong Jin Ying Phay Huai Yu Nur Asykin Ramli Wendy Li Xin Yvonne Tan Ci En Choo Kit Hoong Advisor: Dr Chong Fook Loong Raymond Toh Chun Parng Research Advisory Panel: Professor Aline Wong Associate Professor Tan Ern Ser Dr Lai Ah Eng Dr Kang Soon Hock Associate Professor Pow Choon Piew Dr Kevin Tan Siah Yeow Assistant Professor Chang Jiat Hwee Published Dec 2014 All information is correct at the time of printing. © 2014 Housing & Development Board. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means. Produced by HDB Research and Planning Group ISBN 978-981-09-3827-7 Printed by Oxford Graphic Printers Pte Ltd 11 Kaki Bukit Road 1 #02-06/07/08 Eunos Technolink Singapore 415939 Tel: 6748 3898 Fax: 6747 5668 www.oxfordgraphic.com.sg PUBLIC HOUSING IN SINGAPORE: Residents’ Profile, Housing Satisfaction and Preferences HDB Sample Household Survey 2013 FOREWORD HDB homes have evolved over the years, from basic flats catering to simple, everyday needs, to homes that meet higher aspirational desires for quality living. Over the last 54 years, since its formation, HDB has made the transformation of public housing its key focus. -

Media Release to News Editors SAFRA CHOA CHU KANG TO

Media Release To News Editors SAFRA CHOA CHU KANG TO OFFER TRAMPOLINE PARK, INDOOR CLIMBING FACILITY, INTEGRATED ENTERTAINMENT HUB AND ECO-FRIENDLY FEATURES Expected to draw over 1.4 million visitors annually Come 2022, over 90,000 Singapore Armed Forces (SAF) National Servicemen and their families residing within the north-western part of Singapore, will have convenient access to a wide range of unique facilities for fitness and recreation when SAFRA’s seventh club is built within Choa Chu Kang Park. SAFRA Choa Chu Kang is part of the government’s continuing efforts to recognise NSmen for their contributions towards national defence and is expected to draw over 1.4 million visitors annually. The Groundbreaking Ceremony of the club was graced by Minister for Health and Advisor to Chua Chu Kang Group Representative Constituency Grassroots Organisations Mr Gan Kim Yong. The event was also graced by Senior Minister of State for Defence and President of SAFRA Dr Mohamad Maliki Bin Osman. Unique Fitness Facilities Themed as a ‘Fitness Oasis’, SAFRA Choa Chu Kang will feature many firsts among SAFRA clubs and provide NSmen and their families with many avenues to keep fit. It will be the first among SAFRA clubhouses to house a trampoline park. The trampoline park will be operated by Katapult, and will have an obstacle course section and offer fun-filled trampoline aerobics programmes for both adults and children. The club will also be the first among SAFRA clubhouses to have a sheltered swimming pool, aquagym, sheltered futsal court and sky running track, for NSmen to enjoy, rain or shine.