Jim Carrey Goes to Seaside

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Beneficence of Gayface Tim Macausland Western Washington University, [email protected]

Occam's Razor Volume 6 (2016) Article 2 2016 The Beneficence of Gayface Tim MacAusland Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/orwwu Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation MacAusland, Tim (2016) "The Beneficence of Gayface," Occam's Razor: Vol. 6 , Article 2. Available at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/orwwu/vol6/iss1/2 This Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Western Student Publications at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occam's Razor by an authorized editor of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MacAusland: The Beneficence of Gayface THE BENEFICENCE OF GAYFACE BY TIM MACAUSLAND In 2009, veteran funny man Jim Carrey, best known to the mainstream within the previous decade with for his zany and nearly cartoonish live-action lms like American Beauty and Rent. It was, rather, performances—perhaps none more literally than in that the actors themselves were not gay. However, the 1994 lm e Mask (Russell, 1994)—stretched they never let it show or undermine the believability his comedic boundaries with his portrayal of real- of the roles they played. As expected, the stars life con artist Steven Jay Russell in the lm I Love received much of the acclaim, but the lm does You Phillip Morris (Requa, Ficarra, 2009). Despite represent a peculiar quandary in the ethical value of earning critical success and some of Carrey’s highest straight actors in gay roles. -

Paul Rudd Strikes a Comedic Pose While Bowling for Children Who Stutter

show ad Funnyman with a heart of gold! Paul Rudd strikes a comedic pose while bowling for children who stutter By Shyam Dodge PUBLISHED: 03:33 EST, 22 October 2013 | UPDATED: 03:34 EST, 22 October 2013 30 View comments He's known for being one of the funniest men working in Hollywood today. But Paul Rudd proved he's also got a heart of gold as he hosted his second annual All-Star Bowling Benefit for children who stutter in New York, on Monday. The 44-year-old actor could be seen throughout the fund raising event performing various comedic antics while bowling at the lanes. Gearing up: Paul Rudd hosted his second annual All-Star Bowling Benefit for children who stutter in New York, on Monday The I Love You, Man star taught some of the fundamentals of the sport to the children gathered for the event. But when it came his turn to demonstrate his bowling prowess it appeared he may have needed some practise in the art. Performing a comedic kick in the air after seeming to land the ball in the gutter the surrounding kids erupted into both applause and giggles. Getting a rise: The 44-year-old actor looked to have missed his mark during the event The set up: Rudd got his form down before letting loose But the antics also seemed to have been choreographed to entertain the youngsters, who the star was intent upon helping. Wearing brown suede loafers and tan chinos, Rudd went casual in a simple chequered button down shirt. -

180-TFM153.Feat Btoe

T H E A - Z O F C O M E D Y B Is for... British comedy and the Boat that rocked... ... starring Nick Frost, out of the Wright/Pegg comfort zone and into Richard Curtis' sure-to-be hit comedy. WORDS MATT MUELLER “I don’t like watching comedy,” Even Frost admits it’s as soft-centred and declares Nick Frost. “I know that gooey as Curtis’ previous labours. “What makes me sound like a miserable old else do you expect from bastard but I just don’t.” a Richard Curtis film? This is the most Filling, as he does, the second slot in uncynical, nicest piece of cinema that the comedy A-Z, it’s only natural to you’ll probably see this year. It’s lovely. question the burly funnyman on his own And I managed to watch it without just particular heroes of British comedy during thinking, ‘Oh fuck, I look fat.’” his youth in Essex. “The thing is,” Frost Curtis, an admirer of Hot Fuzz and Shaun continues, “I was a very different person as Of The Dead, wrote the part of cretinous a kid. I only watched slasher pics. When DJ Dave for Frost. “I was tremendously mum and dad were in the pub, they’d let touched,” the actor enthuses. “He’s British me go and hire Halloween or Friday The comedy’s headmaster! And he wrote in a 13th. The first time I remember laughing love scene with Gemma Arterton. Thank like an idiot was The Young Ones. So that you very much, Richard Curtis! We can’t and Blackadder, I guess.” really mention Quantum Of Solace in my And now? “I try not to watch any comedy. -

Famous People with ADHD

Famous People with ADHD Here’s a list of famous people with ADHD. People on the list who lived a long time ago weren’t officially diagnosed with ADHD, but their written history suggests they might have had ADHD. Enjoy the list. You are in good company! Will Smith…actor, singer Jim Carrey…comedian, actor Paris Hilton...actress James Carvel…political analyst Ansel Adams…photographer Pete Rose…Major League Baseball player Glenn Beck…conservative TV and radio personality Michael Phelps…Olympic swimmer Howie Mandell…comedian, actor David Neeleman…founder of Jet Blue Airways Paul Orfalea… founder of Kinko’s John F. Kennedy…U.S. President Jamie Oliver…British celebrity chef Whoopi Goldburg…comedian, actress Justin Timberlake…singer, actor Terry Bradshaw…former Pittsburgh Steelers quarterback Karina Smirnoff…Ukranian professional dancer on Dancing with the Stars Sir Richard Branson…British founder of Virgin Airlines Erin Brockovich-Ellis…legal clerk and activist Ty Pennington…TV personality Scott Eyre…Major League Baseball player Frank Lloyd Wright…architect Bruce Jenner…Olympic athlete Michelle Rodriguez…actress Solange Knowles…singer (Beyonce’s little sister) Charles Schwab…financial expert Greg Louganis… Olympic swimmer Dustin Hoffman…actor Walt Disney…founder of Disney Productions Robin Williams…comedian, actor Steve Jobs…founder of Apple Computers Woody Harrelson…actor Prince Charles…future King of England John Denver…musician Dwight D. Eisenhower… U.S. President, military general Nelson Rockefeller…U.S. Vice President Beethoven…German composer Lewis Carroll…British author of Alice in Wonderland Henry Ford…automobile innovator John Lennon…British musician, member of The Beatles George Bernard Shaw…Irish author Pablo Picasso…Spanish Cubist artist Jackie Stewart…Scottish race car driver Anna Eleanor Roosevelt… U.S. -

With No Catchy Taglines Or Slogans, Showtime Has Muscled Its Way Into the Premium-Cable Elite

With no catchy taglines or slogans, Showtime has muscled its way into the premium-cable elite. “A brand needs to be much deeper than a slogan,” chairman David Nevins says. “It needs to be a marker of quality.” BY GRAHAM FLASHNER ixteen floors above the Wilshire corridor in entertainment. In comedy, they have a sub-brand of doing interesting things West Los Angeles, Showtime chairman and with damaged or self-destructive characters.” CEO David Nevins sits in a plush corner office Showtime can skew male (Ray Donovan, House of Lies) and female (The lined with mementos, including a prop knife Chi, SMILF). It’s dabbled in thrillers (Homeland), black comedies (Shameless), from the Dexter finale and ringside tickets to adult dramas (The Affair), docu-series (The Circus) and animation (Our the Pacquiao-Mayweather fight, which Showtime Cartoon President). It’s taken viewers on journeys into worlds TV rarely presented on PPV. “People look to us to be adventurous,” he explores, from hedge funds (Billions) to management consulting (House of says. “They look to us for the next new thing. Everything we Lies) and drug addiction (Patrick Melrose). make better be pushing the limits of the medium forward.” Fox 21 president Bert Salke calls Showtime “the thinking man’s network,” Every business has its longstanding rivalries. Coke and Pepsi. Marvel and noting, “They make smart television. HBO tries to be more things to more DC. For its first thirty-odd years, Showtime Networks (now owned by CBS people: comedy specials, more half-hours. Showtime is a bit more interested Corporation) ran a distant second to HBO. -

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Sum 2007 "V

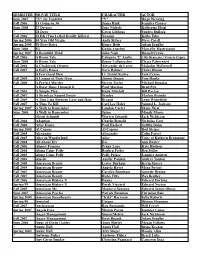

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Sum 2007 "V" for Vendetta "V" Hugo Weaving Fall 2006 13 Going on 30 Jenna Rink Jennifer Garner Sum 2008 27 Dresses Jane Nichols Katherine Heigl ? 28 Days Gwen Gibbons Sandra Bullock Fall 2006 2LDK (Two Lethal Deadly Killers) Nozomi Koike Eiko Spring 2006 40 Year Old Virgin Andy Stitzer Steve Carell Spring 2005 50 First Dates Henry Roth Adam Sandler Sum 2008 8½ Guido Anselmi Marcello Mastroianni Spring 2007 A Beautiful Mind John Nash Russell Crowe Fall 2006 A Bronx Tale Calogero 'C' Anello Lillo Brancato / Francis Capra Sum 2008 A Bronx Tale Sonny LoSpeecchio Chazz Palmenteri Fall 2006 A Clockwork Orange Alexander de Large Malcolm McDowell Fall 2007 A Doll's House Nora Helmer Claire Bloom ? A Few Good Men Lt. Daniel Kaffee Tom Cruise Fall 2005 A League of Their Own Jimmy Dugan Tom Hanks Fall 2000 A Perfect Murder Steven Taylor Michael Douglas ? A River Runs Through It Paul Maclean Brad Pitt Fall 2005 A Simple Plan Hank Mitchell Bill Paxton Fall 2007 A Streetcar Named Desire Stanley Marlon Brando Fall 2005 A Thin Line Between Love and Hate Brandi Lynn Whitefield Fall 2007 A Time To Kill Carl Lee Haley Samuel L. Jackson Spring 2007 A Walk to Remember Landon Carter Shane West Sum 2008 A Walk to Remember Jaime Mandy Moore ? About Schmidt Warren Schmidt Jack Nickleson Fall 2004 Adaption Charlie/Donald Nicholas Cage Fall 2000 After Hours Paul Hackett Griffin Dunn Spring 2005 Al Capone Al Capone Rod Steiger Fall 2005 Alexander Alexander Colin Farrel Fall 2005 Alice in Wonderland Alice Voice of Kathryn Beaumont -

Shapes of You 2 Vocabulary Plus: Prepositions

ShapeS oF YoU 2 Vocabulary plus: prepositions • something you usually do at the weekend • something you like doing on your own 1 Make notes on these topics randomly in the shapes. • a good programme on TV in your country at • a person you met by chance the moment • what you usually do in the evening • the last time you were in a hurry – and why • the last time you went for a run • where you were on New Year’s Day this year • something you did on purpose and regretted • a place where you like going for a walk • the last person you spoke to on the phone • the name of a song by your favourite singer/band • something you have made by hand • the last time you travelled by boat • if you are usually on time or late • where you were in 2008 Fold photocopiable © pearson education limited 2011 131 2 Look at your partner’s notes and guess what they refer to. celebRitY FactS 2 ✃ Grammar: present perfect/past simple Worksheet A Read out your celebrity facts, choosing the correct verb form. Then listen to your partner’s facts and 1 At the age of ten, Justin Timberlake has won/won the 1991 pre-teen Mr America contest. (true) say if they are true or false. 2 Christina Aguilera has recorded/recorded an album in Spanish, but she doesn’t speak the language. (true) 3 When he was a child, Jim Carrey has worn/wore tap shoes to bed, in case his parents needed cheering up in the middle of the night. -

Famous People with ADHD

Este en control de su salud Famosos con ADHD A continuación hay una lista de famosos con ADHD. Las personas de la lista queEste vivieron en hace control mucho tiempo de suno salud recibieron un diagnóstico oficial de ADHD, pero su historia escrita sugiere que pueden haber tenido ADHD. Disfrute la lista. ¡Está en buena compañía! Will Smith … actor, cantante Jim Carrey … comediante, actor Paris Hilton ... actriz James Carvel … analista político Ansel Adams … fotógrafo Pete Rose … Jugador de la Liga Mayor de Béisbol Glenn Beck … personalidad de la radio y la TV de ideas conservadoras Michael Phelps … Nadador olímpico Howie Mandell … comediante, actor David Neeleman … fundador de Jet Blue Airways Paul Orfalea … fundador de Kinko’s John F. Kennedy … Presidente de los EE. UU Jamie Oliver … famoso chef británico Whoopi Goldburg … comediante, actriz Justin Timberlake … cantante, actor Terry Bradshaw … ex mariscal de campo de los Pittsburgh Steelers Karina Smirnoff … Bailarina profesional ucraniana de Dancing with the Stars Sir Richard Branson … Fundador británico de Virgin Airlines Erin Brockovich-Ellis … Asistente legal y activista Ty Pennington … Personalidad de la TV Scott Eyre … Jugador de la Liga Mayor de Béisbol Frank Lloyd Wright … arquitecto Bruce Jenner … Atleta olímpico Michelle Rodriguez … actriz Solange Knowles … cantante (hermana menor de Beyonce) Charles Schwab … experto financiero Greg Louganis … Nadador olímpico Dustin Hoffman … actor Walt Disney … fundador de Disney Productions Robin Williams … comediante, actor Steve Jobs … fundador de Apple Computers Woody Harrelson … actor Príncipe Carlos … futuro Rey de Inglaterra John Denver … músico Dwight D. Eisenhower … Presidente de los EE. UU., general militar Nelson Rockefeller … Vicepresidente de los EE. -

Open Ninth: Conversations Beyond the Courtroom Judges on Film

1 OPEN NINTH: CONVERSATIONS BEYOND THE COURTROOM JUDGES ON FILM: PART 2 EPISODE 36 DECEMBER 5, 2017 HOSTED BY: FREDERICK J. LAUTEN 2 >>Welcome to another episode of “Open Ninth: Conversations Beyond the Courtroom” in the Ninth Judicial Circuit Court of Florida. Now here’s your host, Chief Judge Frederick Lauten. >>CHIEF JUDGE LAUTEN: Well, welcome. We are live, Facebook live and podcasting Phase 2 or Round 2 of Legal Eagles. So Phase 1 was so popularly received, and we’re back for Round 2 with my colleagues and good friend Judge Letty Marques, Judge Bob Egan, and we’re talking about legal movies. And last time there were so many that we just had to call it quits and pick up for Phase 2, so I appreciate that you came back for Round 2, so I’m glad you’re here. You ready to go? >>JUDGE MARQUES: Sure. >>CHIEF JUDGE LAUTEN: Okay, here we go. Watch this high tech. Here’s the deal. We need a box of popcorn, but we’re going to name that movie and then talk a little bit about it. So this is the hint: Who can name that movie from this one slide? >>JUDGE MARQUES: From Runaway Jury? >>CHIEF JUDGE LAUTEN: Did you see the movie? >>JUDGE EGAN: I did; excellent movie. >>CHIEF JUDGE LAUTEN: What’s it about? Do you remember? Anybody remember? >>JUDGE MARQUES: He gets in trouble. Dustin Hoffman gets in trouble at the beginning of the movie with the judge, but I don’t remember why. >>CHIEF JUDGE LAUTEN: I don’t know that I’ve seen this movie. -

Movie Time Descriptive Video Service

DO NOT DISCARD THIS CATALOG. All titles may not be available at this time. Check the Illinois catalog under the subject “Descriptive Videos or DVD” for an updated list. This catalog is available in large print, e-mail and braille. If you need a different format, please let us know. Illinois State Library Talking Book & Braille Service 300 S. Second Street Springfield, IL 62701 217-782-9260 or 800-665-5576, ext. 1 (in Illinois) Illinois Talking Book Outreach Center 125 Tower Drive Burr Ridge, IL 60527 800-426-0709 A service of the Illinois State Library Talking Book & Braille Service and Illinois Talking Book Centers Jesse White • Secretary of State and State Librarian DESCRIPTIVE VIDEO SERVICE Borrow blockbuster movies from the Illinois Talking Book Centers! These movies are especially for the enjoyment of people who are blind or visually impaired. The movies carefully describe the visual elements of a movie — action, characters, locations, costumes and sets — without interfering with the movie’s dialogue or sound effects, so you can follow all the action! To enjoy these movies and hear the descriptions, all you need is a regular VCR or DVD player and a television! Listings beginning with the letters DV play on a VHS videocassette recorder (VCR). Listings beginning with the letters DVD play on a DVD Player. Mail in the order form in the back of this catalog or call your local Talking Book Center to request movies today. Guidelines 1. To borrow a video you must be a registered Talking Book patron. 2. You may borrow one or two videos at a time and put others on your request list. -

Close Encounters of a Different Kind

CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF A DIFFERENT KIND Film producers and directors, studios and financiers from Bollywood and Hollywood are increasing their exposure and stake in each other’s markets. A report by Dipta Joshi. 42 Entertainment Namaste Hollywood: Bollywood stars Katrina Kaif and Akshay Kumar in Namastey London UCH before British director ready films has added immense value to Danny Boyle’s Oscar-award our existing library.” winning film on Mumbai, SPE was one of the first Hollywood ‘Slumdog Millionaire’, took studios to get the government’s approval MIndia to Hollywood, some of its biggest as early as 1996, to set up a presence in studios had already recognised the poten- India. Though it’s first Hindi movie produc- tial in India. tion, ‘Saawariya’ (November 2007), did Investing in offices and other facili- not last long at the theatres, the company ties in India, these Hollywood studios are stays committed to its plans for the Indian now making movies to offer audiences entertainment market. everything that blockbuster Hindi films It has been associated with a number do. Bollywood too is reaching out to the of big- and mid-size productions like ‘Raaz American film industry to garner a share – the mystery continues’, ‘Hello’ and the in the global entertainment business. soon-to-be-released ‘Tere Sang’. Hollywood’s biggest players have Another Hollywood major, Walt Disney stepped up their Indian plans to operate Studios, has tied up with one of India’s and gain a major share in India’s biggest production houses, Yash Raj burgeoning entertainment pie. No longer Films, to co-produce a series of animated are these players content with a few films for Indian audiences. -

Hollywood Sci-Fi, Action, Fantasy and More Auction Press Release

JULIEN’S AUCTIONS - HOLLYWOOD SCI-FI, ACTION, FANTASY AND MORE AUCTION PRESS RELEASE For Immediate Release: JULIEN’S AUCTIONS ANNOUNCES ITS BIGGEST AUCTION YET: HOLLYWOOD SCI-FI, ACTION, FANTASY AND MORE OVER 800 IMPORTANT ITEMS REPRESENTING SOME OF THE MOST ICONIC POP CULTURE DEFINING MOMENTS OF ALL TIME TO HIT THE AUCTION BLOCK, MANY FOR THE FIRST TIME H.R. Giger’s Never-Before-Seen Original “Big Chap” Prototype Translucent Xenomorph Alien Costume to be Exhibited then Sold at Auction for the First Time Al Pacino’s Scarface Three-Piece Pinstripe Suit, Johnny Depp’s Edward Scissorhands Gloves, Bill Murray’s Space Jam Air Jordan 2 Sneakers, Michelle Pfeiffer’s Original “Catwoman” Cowl Worn in Batman Returns and More Among Historic Film Auction Firsts One of the Most Renowned Collections of James Bond Weapons Ever to Come to Auction: Sean Connery’s Walther P5 from his Last Bond film, Never Say Never Again, the Debut of the Walther P99 as Bond’s Preferred Sidearm by Pierce Brosnan in Tomorrow Never Dies, a .38 Smith and Wesson Used by Pierce Brosnan in Die Another Day and more Bruce Willis’ Die Hard Zippo Lighter, Brad Pitt’s Inglourious Basterds Carver Knife, Will Smith’s Independence Day Jet Pilot Flight Suit, Jim Carrey’s Costumes and Props from Ace Ventura, The Mask and Batman Forever, Leonardo DiCaprio’s The Man With The Iron Mask Period Wardrobe, Sigourney Weaver and Winona Ryder’s Flight Suits from Alien Resurrection and More Among Marquee Headliners A Tribute to the 20th Anniversary of the Harry Potter Movie Franchise with an Assortment