Magi and Wise Men: a UU Perspective Phil Roudebush

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

We Three Kings of Orient Are a Sermon by Rev

Carols of Christmas: We Three Kings of Orient Are A Sermon by Rev. Michael Scott The Dublin Community Church December 29, 2013 Matthew 2:1-15 In 1857, the U.S. Supreme Court issued its infamous Dred Scott decision, and the Illinois lawyer and former Congressman, Abraham Lincoln, denounced it as part of a Democratic plot to empower slaveholders. Within a few months, a young bachelor who was working as editor of the Church Journal in New York City set to work on his usual Christmas gift to his nieces and nephews. He was a creative soul who had already at the age of thirty-seven become a “clergyman, author, journalist, book illustrator, and designer of stained glass windows and other ecclesiastical objects.”1 So this year, he decided to write a carol that his little nephews and nieces could use in their annual family Christmas pageant. In December, he headed off on the annual horseback journey from New York to his father’s home near Burlington, Vermont for the holidays. I wonder if he may have traveled through Dublin en route. If so, he would have passed right by this newly constructed meeting house. His name was John Henry Hopkins, Jr., and his father, John Henry Hopkins, Sr. was the Episcopal Bishop of Vermont. He presented his gift to the family, the words and music for a carol called Three Kings of Orient. The children were thrilled with uncle Henry’s song. It made their family pageant a huge smash. Before long the carol had made its way into surrounding churches, and was published by Hopkins in 1863 in his collection, Carols, Hymns, and Songs. -

After Some Time, Three Wise Men, Also Known As Magi, Saw the Brilliant Star in the Sky That Rested Over Where Jesus Was Born

After some time, three Wise Men, also known as magi, saw the brilliant star in the sky that rested over where Jesus was born. The three wise men traveled from where to find the newborn king? 1) From western Europe 2) From northern Israel near Damascus 3) From a distant eastern country* During the Wise Men's' trip, Herod the King of Judah met with the wise men and told them to come back and let him know where the Baby King was so that he could: 1) Go worship him as well* 2) Send his army to protect the family 3) Go and arrest the family The wise men bearing gifts continued to Bethlehem and found Jesus right where the star pointed. Which of these statements is true: 1) Gold was not valuable at that time but myrrh was a valuable spice. 2) Myrrh was used as an anointing oil, frankincense as a perfume, and gold as a valuable* 3) Gold was valuable, but myrrh and frankincense were largely unused A group of men called the magi certainly existed in Jesus’ time. What was their area of expertise: 1) Interpretation of prophecy 2) Astrology 3) Counsellors to kings who made predictions 4) All of the above* 5) None of the above From the second verse of We Three Kings – fill in the blanks: Born a king on ___________ __________ (Bethlehem's plain) Gold I bring to ____________ __________(crown Him again) King forever, __________ _____________ (ceasing never) Over us _______ _______ ________ (all to reign) What did the Western church settle on for the Wise Men names? 1) Raphael, Gabriel and Michael 2) Gabriel, Uriel and Raziel 3) Balthasar, Melchior and Caspar or Gaspar* From the song “Do You Hear What I hear, fill in the blanks: Said the shepherd boy to the ______ _________(mighty king) Do you know what I know In your __________ _______ (palace wall) mighty king Do you know what I know A child, a child _________ ________ _____ _______ (shivers in the cold) Let us bring him ___________ ___ _________ (silver and gold) Epiphany or Three Kings’ Day is also often called Little Christmas. -

Sermon, January 3, 2016 2 Christmas Jeremiah 31:7-14, Psalm 84, Ephesians 1:3-6, 15-19, Matthew 2:1-12 by the Rev. Dr. Kim Mcnamara

Sermon, January 3, 2016 2 Christmas Jeremiah 31:7-14, Psalm 84, Ephesians 1:3-6, 15-19, Matthew 2:1-12 By The Rev. Dr. Kim McNamara As I was taking down and putting away our Christmas decorations on New Year’s Day, my dear husband, John, teased me just a bit about my ritualistic behavior. In many ways, he is right. Christmas, for me, is guided by traditional rituals and symbols. Because I live a very busy life and work in an academic setting divided up into quarterly cycles, the rituals I have marked on the calendar help me to make sure I do everything I want to do in the short amount of time I have to do it in. Along with the rituals, the symbols serve as mental touchstones for me; focusing my attention, my thoughts, my reflections, my memories, and my prayers, on the many meanings of Christmas. My own Christmas rituals start in Advent with two traditional symbols of Christmas, the advent wreath and the nativity. On my birthday, which is exactly two weeks before Christmas, I buy a Christmas tree. (I am not sure what the symbolism is, but it sure is pretty.) As I grade final exams and projects for my students, I reward myself for getting through piles and hours of grading by taking breaks every now and then to decorate for Christmas. According to my ritual schedule, grades and Christmas decorations have to be completed by December 18. I then have two weeks to savor and reflect upon the wonder, beauty, and love of Christmas. -

311.84 KB Area 4

2007 Meeting Minutes Area 4 • November 20, 2007 • October 16, 2007 • September 18, 2007 • August 21, 2007 • June 19, 2007 • May 15, 2007 • April 19-21, 2007 • March 20, 2007 • February 20, 2007 • January 16, 2007 Area 4 Committee Meeting Minutes November 20, 2007 Teleconference Designated Federal Official Martin, Betty - Nashville, TN - LTA Committee Members Present Behnkendorf, Larry - Waterford, MI - Member Bryant, Patricia - Millington, TN - Vice Chair Duquette, Paul - Amherst, WI - Member Hurr, Joe - Dayton, OH - Member Kennedy, Jeff - Louisville, KY - Member Khan, Anne - Chicago, IL - Member Lawler, Mary Ann - Dearborn, MI - Member Meister, David - Franklin, WI - Member Melchior, Jerome - Vincennes, IN - Member Richardson, Lovella - Knoxville, TN - Member Schneider, Ferd - Cincinnati, OH - Chair Wernz, Stanley - Cincinnati, OH - Member Committee Members Absent Amos, Maureen - Chicago, IL - Member Broniarczyk, Robert - Romeoville, IL - Member TAP Staff Coston, Bernie - Atlanta, GA - Director Delzer, Mary Ann - Milwaukee, WI - Analyst McQuin, Sandy - Milwaukee, WI - Manager Odom, Meredith - Brooklyn, NY - Note taker 1 Other Attendees Ray Buschmann Ann Spiotto Regina White Dave Monnier Kelly Wingard Lev Martyniuk John Verwiel Greg Blanchard Robert Mull Welcome Bryant welcomed all members, staff and visitors. Coston thank all members for a very successful TAP year and he thanked the retiring members for all of their hard work and commitment to TAP. Coston will meet with the issue committee program owners to give them an orientation as to expectations, as well as what the members are looking to get out of the program for the upcoming year. Coston sent out an email to the members to pick an issue committee they would like to work on. -

A Godless King (Herod)

Scholars Crossing The Second Person File Theological Studies 10-2017 A Godless King (Herod) Harold Willmington Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/second_person Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, Practical Theology Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Willmington, Harold, "A Godless King (Herod)" (2017). The Second Person File. 15. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/second_person/15 This The Birth of Jesus Christ is brought to you for free and open access by the Theological Studies at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Second Person File by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PHYSICAL BIRTH OF JESUS CHRIST A GODLESS KING (HEROD) THE HEROD THE GREAT FILE STATISTICS ON HIS LIFE Father: Herod Antipater Spouses: Doris, Mariamne I, Mariamne II, Malthace, Cleopatria Sons: Herod Archelaus (Mt. 2:22); Herod Antipas (Mt. 14:1-12); Herod Philip (Mt. 14:3) First mention: Matthew 2:1 Final mention: Matthew 2:19 Meaning of his name: “Seed of a hero” Frequency of his name: Referred to nine times Biblical books mentioning him: One book (Matthew) Occupation: King over Israel Important fact about his life: He was the king who attempted to murder the infant Jesus. STORY OF HIS LIFE The life of this powerful Judean ruler can be summarized as follows: • Herod the Builder It is generally agreed by historians that he was one of the greatest, if not the greatest, builder of the ancient world! He was given the title King of the Jews by the Roman authorities. -

Jesus Christ' Nativity Story

Research and Science Today No. 1(9)/2015 Social Sciences JESUS CHRIST’ NATIVITY STORY Lehel LÉSZAI1 ABSTRACT: MATTHEW AND LUKE PRESENT US JESUS’ GENEALOGY IN THE BEGINNING OF THEIR GOSPEL. MATTHEW’S BOOK OF GENEALOGY OF JESUS CHRIST BEGINS WITH ABRAHAM AND FINISHES WITH JESUS (MT 1,1–17). MATTHEW FOLLOWS THE GENEALOGY OF JOSEPH, WHO IS MENTIONED AS MARY’S HUSBAND. MATTHEW AND LUKE TELL US THAT JOSEPH’S FIANCÉE IS MARY. A YOUNG GIRL AND A CARPENTER ARE CHOSEN BY GOD TO BE THE EARTHLY MOTHER AND FOSTER-FATHER OF HIS ETERNAL SON. GOD CHOOSES SIMPLE AND POOR PEOPLE FOR JESUS AS EARTHLY PARENTS. WE CANNOT READ TOO MUCH IN MATTHEW’S GOSPEL ABOUT THE BIRTH ITSELF, IT IS JUST MENTIONED THAT IT HAPPENED IN BETHLEHEM OF JUDEA DURING THE REIGN OF HEROD THE KING. CONTINUING MATTHEW’S STORY THE LORD’S ANGEL INSTRUCTS JOSEPH IN DREAM TO MAKE THEIR ESCAPE WITH JESUS AND MARY IN EGYPT FROM THE MURDEROUS ANGER OF HEROD. THIS IS ALSO A FULFILLMENT OF AN OLD TESTAMENT PROPHECY: “OUT OF EGYPT I CALLED MY SON” (HOS 11,1). HEROD THE GREAT, THE BLOODTHIRSTY KING DIES AND THE ANGEL OF GOD APPEARS THIS TIME IN EGYPT TO JOSEPH IN HIS DREAM TO DIRECT HIM TO RETURN HOME. MT 2,20 REMINDS US OF THE SAME EPISODE IN MOSES’ STORY (EX 4,19). JESUS RETURNS FROM THE EXILE TO THE PROMISED LAND, BUT HE CANNOT SETTLE DOWN IN JUDEA, IN THE MIDDLE OF THE COUNTRY, IN HIS NATIVE VILLAGE, BUT HE HAS TO GO TO THE BORDER OF THE COUNTRY, TO THE HALF PAGAN GALILEE. -

Peter Saccio

Great Figures of the New Testament Parts I & II Amy-Jill Levine, Ph.D. PUBLISHED BY: THE TEACHING COMPANY 4840 Westfields Boulevard, Suite 500 Chantilly, Virginia 20151-2299 1-800-TEACH-12 Fax—703-378-3819 www.teach12.com Copyright © The Teaching Company, 2002 Printed in the United States of America This book is in copyright. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of The Teaching Company. Amy-Jill Levine, Ph.D. E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Professor of New Testament Studies Vanderbilt University Divinity School/ Vanderbilt University Graduate Department of Religion Amy-Jill Levine earned her B.A. with high honors in English and Religion at Smith College, where she graduated magna cum laude and was a member of Phi Beta Kappa. Her M.A. and Ph.D. in Religion are from Duke University, where she was a Gurney Harris Kearns Fellow and W. D. Davies Instructor in Biblical Studies. Before moving to Vanderbilt, she was Sara Lawrence Lightfoot Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Religion at Swarthmore College. Professor Levine’s numerous publications address Second-Temple Judaism, Christian origins, Jewish-Christian relations, and biblical women. She is currently editing the twelve-volume Feminist Companions to the New Testament and Early Christian Literature for Continuum, completing a manuscript on Hellenistic Jewish narratives for Harvard University Press, and preparing a commentary on the Book of Esther for Walter de Gruyter (Berlin). -

The Illnesses of Herod the Great 1. Introduction 2. Sources of Information

The illnesses of Herod the Great THE ILLNESSES OF HEROD THE GREAT ABSTRACT Herod the Great, Idumean by birth, was king of the Jews from 40BC to AD 4. An able statesman, builder and warrior, he ruthlessly stamped out all perceived opposi- tion to his rule. His last decade was characterised by vicious strife within his family and progressive ill health. We review the nature of his illnesses and suggest that he had meningoencephalitis in 59 BC, and that he died primarily of uraemia and hyper- tensive heart failure, but accept diabetes mellitus as a possible underlying etiological factor. The possibility that Josephus’s classical description of Herod’s disease could be biased by “topos” biography (popular at the time), is discussed. The latter conside- ration is particularly relevant in determining the significance of the king’s reputed worm- infested genital lesions. 1. INTRODUCTION Herod the Great, king of the Jews at the onset of the Christian era, had no Jewish blood in his veins. Infamous in Christian tradition for the massacre of the newborn in Bethlehem, he was nevertheless a vigorous and able ruler, a prolific builder, friend and ally of Rome and founder of an extensive Herodian dynasty which significantly influenced the history of Palestine. His miserable death at the age of 69 years was seen by the Jewish religious fraternity as Jahweh’s just retribution for his vio- lation of Judaic traditions (Ferguson 1987:328-330; Sizoo 1950:6-9). The nature and cause of his illness and death is the subject of this study. 2. SOURCES OF INFORMATION With the exception of fragmentary contributions from Rabbinic tradi- tions, Christian records in the New Testament and evidence from con- temporary coins, Herod’s biography comes to us predominantly through the writings of Flavius Josephus, a Jewish priest of aristocratic descent, military commander in a revolt against Rome, but subsequent recipient of Roman citizenship. -

Sarah EC Maines Marqui Maresca Michael Maresca Dianne Marks

THEATRE AND DANCE FACULTY Cassie Abate Sarah EC Maines Deb Alley Marqui Maresca Ana Carrillo Baer Michael Maresca Natalie Blackman Dianne Marks Greg Bolin Ana Martinez Linda Nenno-Breining Johnny McAllister Kaysie Seitz Brown Amanda McCorkle Elizabeth Buckley Anne McMeeking Trad Burns Brandon R. McWilliams Susan Busa Toby Minor Claire Canavan Jordan Morille Michael Costello Nadine Mozon Michelle Dahlenburg Michelle Nance Tom Delbello Charles Ney Cheri Prough DeVol Michelle Ney Tammy Fife Christa Oliver John Fleming Phillip Owen Misti Galvan William R. Peeler Kevin Gates Bryan Poyser Babs George Aimee Radics Kate Glasheen-Dentino Shannon Richey Brandon Gonzalez Melissa Rodriguez Shelby Hadden Jerry Ruiz Shay Hartung Ishii Sideny Rushing Cathy Hawes Colin Shay Yesenia Herrington Vlasta Silhavy Kaitlin Hopkins LeAnne Smith Randy Huke Shane K. Smith Marcie Jewell Alexander Sterns Erin Kehr Colin D. Swanson Lynzy Lab Caitlin Turnage Laura Lane Neil Patrick Stewart Nick Lawson Scott Vandenberg Eugene Lee Nicole Wesley Clay Liford Yong Suk Yoo STAFF Carl Booker Kim Dunbar Jessica Graham Tina Hyatt Dwight Markus Monica Pasut Jennifer Richards Lori Smith FRONT OF HOUSE STAFF Robert Styers Virtual Theatre Spring 2021 CAST MELCHIOR...............................................................Jeremiah Porter WENDLA.............................................................Kyra Belle Johnson MORITZ............................................................................Riley Clark Department of Theatre and Dance presents ILSE...........................................................................Micaela -

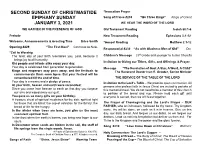

Second Sunday of Christmastide Epiphany

SECOND SUNDAY OF CHRISTMASTIDE *Invocation Prayer EPIPHANY SUNDAY Song of Praise #233 “We Three Kings” Kings of Orient JANUARY 3, 2021 WE HEAR THE WORD OF THE LORD WE GATHER IN THE PRESENCE OF GOD Old Testament Reading Isaiah 60:1-6 Prelude New Testament Reading Ephesians 3:1-12 Welcome, Announcements & Greeting Time Brice Smith *Gospel Reading Matthew 2:1-12 Opening #229 “The First Noel” CANTIQUE DE NOËL Responsorial #236 “As with Gladness Men of Old” DIX *Call to Worship rd The feast day of your birth resembles you, Lord, because it Children’s Message (3 Grade and younger to Junior Church) brings joy to all humanity. Invitation to Giving our Tithes, Gifts, and Offerings & Prayer Old people and infants alike enjoy your day. Your day is celebrated from generation to generation. Message “The Revelation of God: A Star, A Word, A Child” Kings and emperors may pass away, and the festivals to The Reverend Doctor Ivan E. Greuter, Senior Minister commemorate them soon lapse. But your festival will be remembered till the end of time. THE SERVICE OF THE TABLE OF THE LORD Your day is a means and a pledge of peace. Invitation to the Lord’s Table – We practice open communion. All At your birth, heaven and earth were reconciled; persons who profess faith in Jesus Christ are invited to partake of Since you came from heaven to earth on that day you forgave this memorial meal. You do not need to be a member of this church our sins and wiped away our guilt. -

Astronomical Calculations for The

Astronomical Calculations for The Real Star of Bethlehem While the spectacular astronomical signs in the 18 months from May 3 B.C. to December 2 B.C. would have caused wonderful interpretations by astrologers on behalf of Augustus and the Roman Empire, the Magi decided to go to Jerusalem with gifts to a newborn Jewish king. The Magi focused on Judaea and not Rome at this crucial time in history. Let us look at some of the astrological and biblical factors that may have brought the Magi to Jerusalem and then to Bethlehem. Since the New Testament says the Magi saw the “star” rising in the east, it would most naturally be called a “morning star.” The Book of Revelation has Jesus saying of himself, “I am the root and offspring of David, and the bright and morning star.” 1 The apostle Peter also mentioned that Jesus was symbolically associated with “the day star.” 2 The above verses refer to celestial bodies that were well known and recognized in the 1st century and they inspired symbolic messianic interpretation by early Christians. There were several prophecies in Isaiah which generally were interpreted as referring to the Messiah. One has definite astronomical overtones to it. Isaiah said, “The Gentiles shall come to thy light, and kings to the brightness of thy rising.” 3 This prophecy could easily refer to the rising of some star. It would be particularly appropriate to a “morning” or “day” star. Luke, in his Gospel, referring to the celestial symbolism of Isaiah 60:3 which spoke of God as being “the daybreak [the rising] from on high that hath visited us, to give light to them that sit in darkness.” 4 Astronomy and the New Testament These references reveal that celestial bodies were symbolically important to the New Testament writers. -

Star of Bethlehem: an Astronomical and Historical Perspective

THE STAR OF BETHLEHEM: AN ASTRONOMICAL AND HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE By Susan S. Carroll The Star of Bethlehem is one of the most powerful, and enigmatic, symbols of Christianity. Second perhaps only to the Cross of the Crucifixion, the importance of its role in the story of the Nativity of the Christ child is almost on a par with the birth itself. However, the true origin of the Star of Bethlehem has baffled astronomers, historians, and theologians for the past two millennia. For the purposes of this discussion we shall consider four possibilities: That the star was a one-shot occurrence - never before seen and has not been seen since; it was placed in the sky by God to announce the birth of His Son; That the Star was added to the story of the Nativity after the fact; That the Star was a real, documentable astronomical object; That the entire New Testament is fake. If you subscribe to the first theory, then we, as astronomers, have nothing to talk about. It was a supernatural miracle that defies scientific explanation. However, many theologians insist on putting some sort of divine interpretation on Matthew s writings. By admitting that the Star was a natural phenomenon, with an actual scientific explanation, is tantamount to totally removing its heavy symbolic significance. After all, how could something so miraculous have such a mundane explanation? There is a certain amount of credence to the second theory. At the time of Jesus' birth, very few people recognized its significance. The only time the Star is mentioned at all is in the Book of Matthew.