A European Solution to America's Basketball Problem: Reforming

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Southern Illinois University Welcomed Home One of Its All-Time Greats, Naming Bryan Mullins As the School’S 14Th Men’S Basketball Head Coach on March 20, 2019

@SIU_BASKETBALL // #SALUKIS // SIUSALUKIS.COM Contents 2019-20 schedule INTRO TO SALUKI BASKETBALL Date Note Opponent Location Time Watch Schedule/Roster ..................................1 Nov. 5 Illinois Wesleyan Carbondale, Ill. 7 p.m. ESPN3 Banterra Center ............................... 2-9 Sunshine Slam 1967 NIT Championship ............. 10-11 Nov. 8 vs. UTSA Kissimmee, Fla. 6:30 p.m. CT FloHoops 1977 Sweet 16 .................................... 12 Nov. 9 vs. Delaware Kissimmee, Fla. 2 p.m. CT FloHoops Rich Herrin Era ................................... 13 Nov. 10 vs. Oakland Kissimmee, Fla. 12 p.m. CT FloHoops 2002 Sweet 16 ..............................14-15 Nov. 16 ^ San Francisco Carbondale, Ill. 7 p.m. ESPN3 Six-Straight NCAAs ......................16-17 Nov. 19 at Murray State Murray, Ky. 7 p.m. ESPN+ 2007 Sweet 16 ..............................18-19 Nov. 26 NC Central Carbondale, Ill. 7 p.m. ESPN+ Salukis in the NBA ....................... 20-21 Dec. 1 at Saint Louis St. Louis, Mo. 3 p.m. Fox Sports Midwest Academics / Strength ................22-23 Dec. 4 Norfolk State Carbondale, Ill. 7 p.m. ESPN+ Dec. 7 at Southern Miss Hattiesburg, Miss. TBD TBD 2019-20 PREVIEW Dec. 15 at Missouri Columbia, Mo. 3 p.m. SEC Network Season Outlook .................................25 Dec. 18 Hampton Carbondale, Ill. 7 p.m. ESPN+ Player Bios (Alphabetical) ........ 26-39 Dec. 21 Southeast Missouri Carbondale, Ill. 3 p.m. ESPN3 Head Coach Bryan Mullins .......40-41 Dec. 30 * at Indiana State Terre Haute, Ind. 7 p.m. MVC TV Network Coaching & Support Staff ........ 42-46 Jan. 4 * Illinois State Carbondale, Ill. 3 p.m. ESPN3 Quick Facts .........................................47 Jan. 7 * Valparaiso Carbondale, Ill. 7 p.m. -

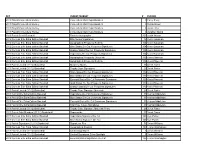

Set Insert/Subset # Player

SET INSERT/SUBSET # PLAYER 2011 Playoff Contenders Hockey Contenders Match-Ups Booklets 8 Corey Perry 2011 Playoff Contenders Hockey Contenders Match-Ups Booklets 8 Dustin Brown 2011 Playoff Contenders Hockey Contenders Match-Ups Booklets 8 Jonas Hiller 2011 Playoff Contenders Hockey Contenders Match-Ups Booklets 8 Jonathan Quick 2013 Panini Select Baseball Rookies Autographs 202 Justin Wilson 2012 Donruss Elite Extra Edition Baseball Elite Series Signatures 12 Kevin Gausman 2012 Donruss Elite Extra Edition Baseball Autographed Prospects Red Ink 104 Kevin Gausman 2012 Donruss Elite Extra Edition Baseball Blue Status Die Cut Prospects Signatures 104 Kevin Gausman 2012 Donruss Elite Extra Edition Baseball Orange Status Die Cut Prospects Signatures 104 Kevin Gausman 2012 Donruss Elite Extra Edition Baseball Aspirations Die Cut Prospects Signatures 104 Kevin Gausman 2012 Donruss Elite Extra Edition Baseball Autographed Prospects Green Ink 119 Kevin Plawecki 2012 Donruss Elite Extra Edition Baseball Autographed Prospects Red Ink 119 Kevin Plawecki 2011 Panini Limited (11-12) Basketball Masterful Marks 18 Derek Fisher 2011 Panini Limited (11-12) Basketball Trophy Case Signatures 29 Derek Fisher 2012 Donruss Elite Extra Edition Baseball Black Status Die Cut Prospect Signatures 119 Kevin Plawecki 2012 Donruss Elite Extra Edition Baseball Blue Status Die Cut Prospects Signatures 119 Kevin Plawecki 2012 Donruss Elite Extra Edition Baseball Emerald Status Die Cut Prospects Signatures 119 Kevin Plawecki 2012 Donruss Elite Extra Edition Baseball Gold -

Tomas Van Den Spiegel Re-Elected As ULEB President View Artcile

ULEB Press Release Tomas Van Den Spiegel re-elected as ULEB President At yesterday’s ULEB General Assembly current President Tomas Van Den Spiegel was re- elected for the 2020-2024 term. Tomas Van Den Spiegel: “I am happy to be re-elected and thank all member leagues for their confidence. I am looking forward to representing each one of them again for the coming 4 years. It is important to me to maintain the current momentum and togetherness that we have established between all members during my first term. This has culminated amongst others in the competition complaint that was recently filed to the European Commission versus Euroleague. Next to protecting the European sports model, it is essential that we as domestic leagues stand our ground and protect national league basketball in general. Furthermore I will look to build on the improved international relations that have allowed ULEB to be actively involved in discussions and decision making on a number of levels, always looking to protect our members’ interests. As for the future of ULEB we are aiming to optimize the internal functioning of the organization with the installment of a strategic committee that will be exploring ULEB expansion and partnership development amongst other things.” About ULEB: ULEB, the association of the European Basketball Leagues, was founded in 1992 and aims to develop and to defend the rights of the European domestic leagues and their clubs. ULEB members today include ACB (Spain), LNB (France), BBL (Germany), HEBA (Greece), PBL (Belgium), PLK (Poland), DBL (Netherlands), Legabasket (Italy), VTB United League, LKL (Lithuania), BSL (Israel). -

Single-File Crabbing in Port Orford

C M C M Y K Y K DEADLY STAMPEDE WAR OF THE ROSES Sixty-one perish after Ivory Coast fireworks show, A7 Pac-12’s Stanford beats Wisconsin, B1 Serving Oregon’s South Coast Since 1878 WEDNESDAY,JANUARY 2, 2013 theworldlink.com I 75¢ Single-file crabbing in Port Orford BY JESSIE HIGGINS get a long stretch of stormy weath- along the channel as the tide reced- pass each other. It really slows the negating the need for dredging. But The World er that fills the port with sand.” ed and run their propellers. The operation down.” that would mean less protection The Port of Port Orford has not hope was, the action would push Anderson and the 40 to 60 fish- from storms. PORT ORFORD — Commercial been dredged since 2009, when enough sand out to sea with the ermen who use the port are looking “We’re looking at all our crabbers around Oregon headed Congress banned federal earmark- tide to deepen the channel for the for a more long-term solution to options,”Anderson said. out to collect their pots Monday, ing. Now, the U.S. Army Corps of crab season. the dredging problem. One possi- The Port of Port Orford is a nat- the first day of this year’s crab sea- Engineers ranks Oregon ports by But the weather was stormy in bility is for the port to seek out ural deep water port. Unlike most son. the amount of goods they export. the days leading up to the season, grant money to purchase its own Oregon ports, it is not connected to But in Port Orford, the fisher- Only the top exporting ports are and the fishermen didn’t want to dredging equipment. -

Akasvayu Girona

AKASVAYU GIRONA OFFICIAL CLUB NAME: CVETKOVIC BRANKO 1.98 GUARD C.B. Girona SAD Born: March 5, 1984, in Gracanica, Bosnia-Herzegovina FOUNDATION YEAR: 1962 Career Notes: grew up with Spartak Subotica (Serbia) juniors…made his debut with Spartak Subotica during the 2001-02 season…played there till the 2003-04 championship…signed for the 2004-05 season by KK Borac Cacak…signed for the 2005-06 season by FMP Zeleznik… played there also the 2006-07 championship...moved to Spain for the 2007-08 season, signed by Girona CB. Miscellaneous: won the 2006 Adriatic League with FMP Zeleznik...won the 2007 TROPHY CASE: TICKET INFORMATION: Serbian National Cup with FMP Zeleznik...member of the Serbian National Team...played at • FIBA EuroCup: 2007 RESPONSIBLE: Cristina Buxeda the 2007 European Championship. PHONE NUMBER: +34972210100 PRESIDENT: Josep Amat FAX NUMBER: +34972223033 YEAR TEAM G 2PM/A PCT. 3PM/A PCT. FTM/A PCT. REB ST ASS BS PTS AVG VICE-PRESIDENTS: Jordi Juanhuix, Robert Mora 2001/02 Spartak S 2 1/1 100,0 1/7 14,3 1/4 25,0 2 0 1 0 6 3,0 GENERAL MANAGER: Antonio Maceiras MAIN SPONSOR: Akasvayu 2002/03 Spartak S 9 5/8 62,5 2/10 20,0 3/9 33,3 8 0 4 1 19 2,1 MANAGING DIRECTOR: Antonio Maceiras THIRD SPONSOR: Patronat Costa Brava 2003/04 Spartak S 22 6/15 40,0 1/2 50,0 2/2 100 4 2 3 0 17 0,8 TEAM MANAGER: Martí Artiga TECHNICAL SPONSOR: Austral 2004/05 Borac 26 85/143 59,4 41/110 37,3 101/118 85,6 51 57 23 1 394 15,2 FINANCIAL DIRECTOR: Victor Claveria 2005/06 Zeleznik 15 29/56 51,8 13/37 35,1 61/79 77,2 38 32 7 3 158 10,5 MEDIA: 2006/07 Zeleznik -

Fastest 40 Minutes in Basketball, 2012-2013

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Arkansas Men’s Basketball Athletics 2013 Media Guide: Fastest 40 Minutes in Basketball, 2012-2013 University of Arkansas, Fayetteville. Athletics Media Relations Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/basketball-men Citation University of Arkansas, Fayetteville. Athletics Media Relations. (2013). Media Guide: Fastest 40 Minutes in Basketball, 2012-2013. Arkansas Men’s Basketball. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.uark.edu/ basketball-men/10 This Periodical is brought to you for free and open access by the Athletics at ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arkansas Men’s Basketball by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TABLE OF CONTENTS This is Arkansas Basketball 2012-13 Razorbacks Razorback Records Quick Facts ........................................3 Kikko Haydar .............................48-50 1,000-Point Scorers ................124-127 Television Roster ...............................4 Rashad Madden ..........................51-53 Scoring Average Records ............... 128 Roster ................................................5 Hunter Mickelson ......................54-56 Points Records ...............................129 Bud Walton Arena ..........................6-7 Marshawn Powell .......................57-59 30-Point Games ............................. 130 Razorback Nation ...........................8-9 Rickey Scott ................................60-62 -

Author: Ennio Terrasi Borghesan TEAM ROSTERS AX ARMANI EXCHANGE Milano

Umberto Gandini, LBA President | Photo Credits: M.Ceretti / Ciamillo-Castoria LEGABASKET 2020-2021 by Sportando | Author: Ennio Terrasi Borghesan TEAM ROSTERS AX ARMANI EXCHANGE Milano SURNAME NAME PREVIOUS TEAM FROM YOB POS PASS END OPT BILIGHA Paul confirmed - 1990 FC ITA 2022 BROOKS Jeff confirmed - 1989 FC ITA 2021 CINCIARINI Andrea confirmed - 1986 G ITA 2022 DATOME Luigi Fenerbahce TUR 1987 F ITA 2023 DELANEY Malcom Barcelona SPA 1989 G USA 2022 HINES Kyle CSKA VTB 1986 FC USA 2022 LEDAY Zach Zalgiris LIT 1994 FC USA 2022 MICOV Vladimir confirmed - 1985 F SRB 2021 MORASCHINI Riccardo confirmed - 1991 GF ITA 2022 MORETTI Davide Texas Tech NCAA 1998 G ITA 2023 2025 Ettore MESSINA PUNTER Kevin Crvena Zvezda ABA 1993 G USA 2021 RODRIGUEZ Sergio confirmed - 1986 G SPA 2022 confirmed ROLL Michael confirmed - 1987 GF TUN 2021 2022 (2024) SHIELDS Shavon Baskonia SPA 1994 GF DEN 2022 TARCZEWSKI Kaleb confirmed - 1993 C USA 2023 HONOURS REGISTERED PLAYERS 15 out of 18 28 Scudetti (last: 2018) CHOSEN FORMULA 6 Italian Cup (last: 2017) 6+6 4 Italian SuperCup (last: 2020) NON-EU PLAYERS 3 Euroleague (last: 1988); 3 Saporta Cup (last: 1976); 2 7 (out of 7) Korac Cup (last: 1993); 1 Intercontinental Cup (1987) Seasons played in Serie A1: 80 Mediolanum Forum (12,331 seats) AX ARMANI EXCHANGE Milano 1st Euroleague Game 02.10 - @ Bayern Munich 1st Home Game Milano celebrating with the Supercoppa trophy | Photo Credits: M.Longo / Ciamillo-Castoria 09.10 - vs ASVEL The Ultimate Front-Runner Olimpia Milano enters Year II of the Messina Era with only one word in mind, when it comes down to Italian ‘ball: Win. -

• Guest Speakers in Max Utsler's J512 Principles of Broadcasting Class This Past Semester Included: Laura Lombardi, Textcast

• Guest speakers in Max Utsler’s J512 Principles of Broadcasting class this past semester included: Laura Lombardi, Textcaster; Brian Bracco, vice president, Hearst Corporation; Dan Mulvenon, vice president, National Cable Television Cooperative; Bruce Linton, J-School professor emeritus; Bob Wells, former FCC member; Kent Cornish, executive director, Kansas Association of Broadcasters; Bryan Busby, KMBC-TV meteorologist; and Rob Walch, president, Podcasting 411. • Connie Schultz, Pulitzer-Prize winning columnist for the Cleveland Plain Dealer, spoke April 28 to Barbara Barnett's Media and Society class. • Jackie Bunnell, an account researcher for Callahan Creek in Lawrence, spoke to Sue Novak’s Ethics class on April 27. • Dr. Teresa Trumbly Lamsam will join the J-School for the 2011 academic year as a visiting professor. She is taking a leave from her position at the University of Nebraska–Omaha, where she is an associate professor in the School of Communication with an appointment in the Native American Studies Program. During her year with us, she will be working on outreach to Native American communities, continuing her research on developing a theory of historical trauma, and exploring grant opportunities associated with Native American health communications. She also will be teaching and making presentations about her work. Her professional background included serving as editor of The Osage Nation News, working as a translator in Austria (she’s fluent in German), and copy-editing and design at the Lubbock Avalanche in Texas. At UNO, she’s taught Introduction to Mass Communication, Media Writing, News Editing, Research Methods and Public Affairs Reporting. She is a graduate of the University of Missouri (PhD and MA) and Abilene Christian University (BA). -

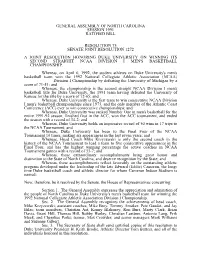

Senate Joint Resolution 1272

GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF NORTH CAROLINA SESSION 1991 RATIFIED BILL RESOLUTION 75 SENATE JOINT RESOLUTION 1272 A JOINT RESOLUTION HONORING DUKE UNIVERSITY ON WINNING ITS SECOND STRAIGHT NCAA DIVISION I MEN'S BASKETBALL CHAMPIONSHIP. Whereas, on April 6, 1992, the student athletes on Duke University's men's basketball team won the 1992 National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division I Championship by defeating the University of Michigan by a score of 71-51; and Whereas, the championship is the second straight NCAA Division I men's basketball title for Duke University, the 1991 team having defeated the University of Kansas for the title by a score of 72-65; and Whereas, Duke University is the first team to win consecutive NCAA Division I men's basketball championships since 1973, and the only member of the Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC) ever to win consecutive championships; and Whereas, Duke University was ranked Number One in men's basketball for the entire 1991-92 season, finished first in the ACC, won the ACC tournament, and ended the season with a record of 34-2; and Whereas, Duke University holds an impressive record of 50 wins in 17 trips to the NCAA Tournament; and Whereas, Duke University has been to the Final Four of the NCAA Tournament 10 times, making six appearances in the last seven years; and Whereas, Head Coach Mike Krzyzewski is only the second coach in the history of the NCAA Tournament to lead a team to five consecutive appearances in the Final Four, and has the highest winning percentage for active coaches in NCAA -

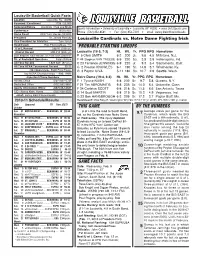

Probable Starting Lineups This Game by the Numbers

Louisville Basketball Quick Facts Location Louisville, Ky. 40292 Founded / Enrollment 1798 / 22,000 Nickname/Colors Cardinals / Red and Black Sports Information University of Louisville Louisville, KY 40292 www.UofLSports.com Conference BIG EAST Phone: (502) 852-6581 Fax: (502) 852-7401 email: [email protected] Home Court KFC Yum! Center (22,000) President Dr. James Ramsey Louisville Cardinals vs. Notre Dame Fighting Irish Vice President for Athletics Tom Jurich Head Coach Rick Pitino (UMass '74) U of L Record 238-91 (10th yr.) PROBABLE STARTING LINEUPS Overall Record 590-215 (25th yr.) Louisville (18-5, 7-3) Ht. Wt. Yr. PPG RPG Hometown Asst. Coaches Steve Masiello,Tim Fuller, Mark Lieberman F 5 Chris SMITH 6-2 200 Jr. 9.8 4.5 Millstone, N.J. Dir. of Basketball Operations Ralph Willard F 44 Stephan VAN TREESE 6-9 220 So. 3.5 3.9 Indianapolis, Ind. All-Time Record 1,625-849 (97 yrs.) C 23 Terrence JENNINGS 6-9 220 Jr. 9.3 5.4 Sacramento, Calif. All-Time NCAA Tournament Record 60-38 G 2 Preston KNOWLES 6-1 190 Sr. 14.9 3.7 Winchester, Ky. (36 Appearances, Eight Final Fours, G 3 Peyton SIVA 5-11 180 So. 10.7 2.9 Seattle, Wash. Two NCAA Championships - 1980, 1986) Important Phone Numbers Notre Dame (19-4, 8-3) Ht. Wt. Yr. PPG RPG Hometown Athletic Office (502) 852-5732 F 1 Tyrone NASH 6-8 232 Sr. 9.7 5.8 Queens, N.Y. Basketball Office (502) 852-6651 F 21 Tim ABROMAITIS 6-8 235 Sr. -

Faculty and Staff News Student News and Opportunities

Web Version | Update preferences | Unsubscribe Like Tweet Forward TABLE OF CONTENTS Faculty and Staff News • Faculty and Staff News Associate Dean of Graduate Studies Scott Reinardy was elected to • Student News and a three-year term on the Association for Education in Journalism and Opportunities Mass Communication Publications Committee. Reinardy was elected • Jobs and internships in an AEJMC national election. • Campaigns Presentations Assistant Professor Yvonnes Chen’s co-authored work is now published online in Mass Communication and Society. Learn more • In Memoriam about her work, “Processing of sexual media messages improves due • Alumni Update to media literacy effects on perceived message desirability,” here: • Mark Your Calendar http://bit.ly/1GCpzJu Chen completed an Introduction to Functional Magnetic Resonance CONTACT US Imaging (fMRI) workshop with selected faculty from KU Medical Center and KU-Lawrence campuses. Hosted by Hoglund Brain Send us your news Imaging Center faculty and research associates, this workshop Submit items to introduced the basics of fMRI, principles of an fMRI experimental [email protected] by 5 paradigm, and fMRI data collection and analysis. p.m. Friday for the following week's Associate Professor Tien Lee gave a research talk on April 29 at newsletter. National Chengchi University in Taipei, Taiwan. The topic was how to study Taiwanese and American citizens’ political ideologies. Guest speakers in the Journalism 540 Sports, Media and Society class this semester included: Dennis Dodd, CBS.com Steve -

Rosters Set for 2014-15 Nba Regular Season

ROSTERS SET FOR 2014-15 NBA REGULAR SEASON NEW YORK, Oct. 27, 2014 – Following are the opening day rosters for Kia NBA Tip-Off ‘14. The season begins Tuesday with three games: ATLANTA BOSTON BROOKLYN CHARLOTTE CHICAGO Pero Antic Brandon Bass Alan Anderson Bismack Biyombo Cameron Bairstow Kent Bazemore Avery Bradley Bojan Bogdanovic PJ Hairston Aaron Brooks DeMarre Carroll Jeff Green Kevin Garnett Gerald Henderson Mike Dunleavy Al Horford Kelly Olynyk Jorge Gutierrez Al Jefferson Pau Gasol John Jenkins Phil Pressey Jarrett Jack Michael Kidd-Gilchrist Taj Gibson Shelvin Mack Rajon Rondo Joe Johnson Jason Maxiell Kirk Hinrich Paul Millsap Marcus Smart Jerome Jordan Gary Neal Doug McDermott Mike Muscala Jared Sullinger Sergey Karasev Jannero Pargo Nikola Mirotic Adreian Payne Marcus Thornton Andrei Kirilenko Brian Roberts Nazr Mohammed Dennis Schroder Evan Turner Brook Lopez Lance Stephenson E'Twaun Moore Mike Scott Gerald Wallace Mason Plumlee Kemba Walker Joakim Noah Thabo Sefolosha James Young Mirza Teletovic Marvin Williams Derrick Rose Jeff Teague Tyler Zeller Deron Williams Cody Zeller Tony Snell INACTIVE LIST Elton Brand Vitor Faverani Markel Brown Jeffery Taylor Jimmy Butler Kyle Korver Dwight Powell Cory Jefferson Noah Vonleh CLEVELAND DALLAS DENVER DETROIT GOLDEN STATE Matthew Dellavedova Al-Farouq Aminu Arron Afflalo Joel Anthony Leandro Barbosa Joe Harris Tyson Chandler Darrell Arthur D.J. Augustin Harrison Barnes Brendan Haywood Jae Crowder Wilson Chandler Caron Butler Andrew Bogut Kentavious Caldwell- Kyrie Irving Monta Ellis