The Gettysburg Cyclorama on Exhibit Until About 1895

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winter 2017 Issue

Upcoming Exhibitions WINTER 2018 MORE THAN SELF: LIVING THE VIETNAM WAR Cyclorama RESTORATION UPDATES Physical Updates OLGUITA’S GARDEN Visitor Experiences MIDTOWN ENGAGEMENT Partnerships ATL COLLECTIVE WINTER 2018 WINTER 2017 HISTORY MATTERS . TABLE OF CONTENTS 02–07 22–23 Introduction Kids Creations More than Self: Living the Vietnam War Living the Vietnam than Self: More 08–15 24–27 Exhibition Updates FY17 in Review 16–18 28 Physical Updates Accolades 19 29–33 Midtown Engagement History Makers Cover Image | Boots worn by American soldier in Vietnam War and featured in exhibition, in exhibition, and featured War American soldier in Vietnam by Image worn | Boots Cover 20–21 34–35 Partnerships Operations & Leadership ATLANTA HISTORY CENTER WINTER 2017 NEWSLETTER INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION History is complex, hopeful, and full of fascinating stories of As I walk through the new spaces of our campus, I think back everyday individuals. The people who have created the story of Atlanta through 91 years of institutional history. We should all be proud and are both remarkable and historic. The Atlanta History Center, has amazed at the achievements and ongoing changes that have taken done a great job of sharing the comprehensive stories of Atlanta, place since a small group of 14 historically minded citizens gathered in MESSAGE our region, and its people to the more than 270,000 individuals we MESSAGE 1926 to found the Atlanta Historical Society, which has since become serve annually. Atlanta History Center. The scope and impact of the Atlanta History Center has expanded As Atlanta’s History Center of today, we understand we must find significantly, and we have reached significant milestones. -

Faqs on the Battle of Atlanta Cyclorama Move

FAQs on Atlanta History Center’s Move Why is The Battle of Atlanta cyclorama painting moving to of The Atlanta History Center? Battle of In July 2014, Mayor Kasim Reed announced the relocation Atlanta and the restoration of this historic Atlanta Cyclorama painting Cyclorama The Battle of Atlanta to the History Center, as part of a 75 Painting year license agreement with the City of Atlanta. Atlanta History Center has the most comprehensive collection of Civil War artifacts at one location in the nation, including the comprehensive exhibition Turning Point: The American Civil War, providing the opportunity to make new connections between the Cyclorama and other artifacts, archival records, photographs, rare books, and contemporary research. As new stewards of the painting, Atlanta History Center provides a unique opportunity to renew one of the city’s most important cultural and historic artifacts. Where will the painting and locomotive be located at the History Center? The Battle of Atlanta painting will be housed in a custom– built, museum-quality environment, in the Lloyd and Mary Ann Whitaker Cyclorama Building, located near the corner of West Paces Ferry Road and Slaton Drive, directly behind Veterans Park, and connected to the Atlanta History Museum atrium through Centennial Olympic Games Museum hallway. The Texas locomotive will be displayed in a 2,000-square-foot glass-fronted gallery connecting Atlanta History Museum with the new cyclorama building. What is the condition of the painting? “Better than you might think,” said Gordon Jones, Atlanta History Center Senior Military Historian and a co-leader of the Cyclorama project team. -

Gettysburg National Military Park

GETTYSBURG NATIONAL MILITARY PARK PENNSYLVANIA Lee did not know until June 28 that the the powerful Confederate forces smashed Delay dogged Confederate preparations, cided upon a massive frontal assault against Union army—now commanded by Gen. into the Union lines. and the morning wore away; with it went Meade's center. A breakthrough there GETTYSBURG George G. Meade—was following him. Back through the town fled the men in Lee's hopes for an early attack. would cut the Federal army in half and Then, realizing that a battle was imminent, blue. Many units fought heroic rearguard Just after noon, Union Gen. Daniel Sickles might open the way to that decisive victory Lee ordered his scattered forces to concentrate actions to protect their retreating comrades. pushed his troops westward from Cemetery the Confederacy needed. NATIONAL MILITARY PARK at Cashtown, 8 miles west of Gettysburg. By 5:30 p.m., the Union remnants were hur Ridge. His new line formed a salient with His fighting blood up, Lee waved aside Two days later, on June 30, Gen. John riedly entrenching south of Gettysburg on its apex at the Peach Orchard on the Emmits- Longstreet's objections to a frontal assault Scene of the climactic Battle of Gettysburg, a turning point of the American Buford's Union cavalry contacted a Confed Cemetery Hill, where Gen. Winfield Scott burg Road. This powerful intrusion further against the strong Union line. Pointing to complicated Lee's attack plan. Civil War, and the place where President Abraham Lincoln made his cele erate detachment near Gettysburg, then oc Hancock—a rock in adversity—rallied their Cemetery Ridge, he exclaimed: "The enemy Finally, at 4 p.m., Longstreet's batteries is there, and I am going to strike him." brated Gettysburg Address. -

The Gettysburg National Military Park Museum and Visitor Center

C A S E S T U D Y History’s KeeperA lone cannon stands in a field at the Gettysburg Battlefield. The new Gettysburg National Military Park Museum and Visitor Center opened in 2008 to provide visitors with an understanding of the scope and magnitude of the sacrifices made at Gettysburg. The Battle of Gettysburg was a turning point in the Civil War, the Union victory that ended Gen. Robert E. Lee’s second invasion of the North in 1863. It was the war’s bloodiest battle with 51,000 casualties and the setting for President Abraham Lincoln’s “Gettysburg Address.” © Getty Images BY TATYANA SHINE, P.E.; AND ELIZABETH PAUL Museums consume mas- he Gettysburg National conditions required for preserva- Military Park Museum tion and reducing long-term energy sive amounts of energy. and Visitor Center houses costs. Since its opening in 2008, From exhibit lighting to what most Civil War the facilities team has maintained Tenthusiasts consider to be the larg- and improved the original energy- temperature control and est collection of civil war artifacts, efficient design by performing a including a massive historic oil daily walk-through to check build- relative humidity, their painting that depicts the battle. ing systems and look for ways to Storing these pieces of American improve performance. The careful costs are much higher history requires a specific dry-bulb attention to operations demonstrates when compared to a temperature and relative humidity that it doesn’t matter how efficiently level be maintained on a daily basis. a building is designed, it will never similar size traditional The museum and visitor center perform to its full potential without design team selected a geothermal a knowledgeable staff to operate office building. -

NPS Buys Ford Dealership to Clear Gettysburg First-Day Field

THE “OLD LINER” NEWSLETTER EDITOR’S NOTE: IN MEMORIAM If you received this issue of the Harry Dorsey BCWRT Newsletter in the mail, 12/9/43 – 8/29/07 please check the mailing label on On August 29, 2007, the Baltimore Civil War Roundtable’s long-serving the outside page. If there is a RED Treasurer passed away. Harry Dorsey had been active in the BCWRT almost X you will continue to receive a since the group’s inception. His dedication and interest helped to make the copy of the monthly newsletter via Roundtable what it is today. On behalf of the members of the Baltimore Civil War Roundtable, The Board of Directors and I offer deep condolences to Harry’s the US Postal Service. If there is family. He will be missed. no RED X, next month’s He is survived by his wife Ruth and his brother Joe Dorsey. newsletter will be the last one you will receive in the mail. Please resembling their appearance when exist at the time of the battle, and notify me if you wish to continue they were the scenes of bloody replant 115 acres of trees that were struggles between the forces of North there but have since disappeared. to receive the newsletter via and South. "If you can think of an This year, work is focusing on USPS. I can be reached by mail at historic landscape the same way that clearing out trees around Devil's Den, 17 Fusting Ave, 1W, Catonsville, we're used to thinking of historic a rocky outcropping that saw bitter MD 21228 or by phone at 410- structures, the whole reason for doing fighting, and along a section of the 788-3525. -

Itinerary Planning Tips and Suggested Itineraries

Itinerary Planning Tips and Suggested Itineraries Bringing your group to Gettysburg is simple. Use these tips and suggested itineraries to plan your trip, or contact one of our Receptive companies to help plan your stay. Itinerary Planning Tips Is this your group’s first time visiting Gettysburg? Limited on the amount of time you are able to spend in the area? Begin your visit getting acquainted with Gettysburg’s battlefield at one of these locations: Gettysburg National Military Park Museum & Visitor Center- (approximately 2 hours) The featured film “A New Birth of Freedom” will orient your group to the Battle of Gettysburg and the American Civil War. Also see the restored “Battle of Gettysburg” cyclorama painting – the largest painting in the country depicting the third day’s battle. Afterwards, take the group through the museum portion, where the story of the Battle and the war is told through 12 galleries that include artifacts, interactive exhibits and additional films. Gettysburg Diorama at the Gettysburg History Center- (approximately 45 minutes) See the entire 6,000-acre battlefield in 3-D miniature as you hear the story of the three-day battle and how it progressed. Learn and visualize the battle as it is narrated with light and sound effects. Allow time for the group to have lunch on their own, dine in a historic tavern or provide boxed lunches. Looking to picnic? Head to Gettysburg Recreation Park- home to the Biser Fitness Trail, Walking Path and a skate park, four pavilions, five playing fields including basketball, baseball, soccer, and football, an amphitheater, two shuffle board pads and playgrounds. -

Cover of 1992 Edition) This Scene from the Gettysburg Cyclorama Painting

cover of 1992 edition) (cover of 1962 edition) This scene from the Gettysburg Cyclorama painting by Paul Philippoteaux potrays the High Water Mark of the Confederate cause as Southern Troops briefly pentrate the Union lines at the Angle on Cemetery Ridge, July 3, 1863. Photo by Walter B. Lane. GETTYSBURG National Military Park Pennsylvania by Frederick Tilberg National Park Service Historical Handbook Series No. 9 Washington, D.C. 1954 (Revised 1962, Reprint 1992) Contents a. THE SITUATION, SPRING 1863 b. THE PLAN OF CAMPAIGN c. THE FIRST DAY The Two Armies Converge on Gettysburg The Battle of Oak Ridge d. THE SECOND DAY Preliminary Movements and Plans Longstreet Attacks on the Right Warren Saves Little Round Top Culp's Hill e. THE THIRD DAY Cannonade at Dawn: Culp's Hill and Spangler's Spring Lee Plans a Final Thrust Lee and Meade Set the Stage Artillery Duel at One O'clock Climax at Gettysburg Cavalry Action f. END OF INVASION g. LINCOLN AND GETTYSBURG Establishment of a Burial Ground Dedication of the Cemetery Genesis of the Gettysburg Address The Five Autograph Copies of the Gettysburg Address Soldiers' National Monument The Lincoln Address Memorial h. ANNIVERSARY REUNIONS OF CIVIL WAR VETERANS i. THE PARK j. ADMINISTRATION k. SUGGESTED READINGS l. APPENDIX: WEAPONS AND TACTICS AT GETTYSBURG m. GALLERY: F. D. BRISCOE BATTLE PAINTINGS For additional information, visit the Web site for Gettysburg National Military Park Historical Handbook Number Nine 1954 (Revised 1962) This publication is one of a series of handbooks describing the historical and archeological areas in the National Park System administered by the National Park Service of the United States Department of the Interior. -

Visitor Attraction Case Study Cyclorama Exhibit - Atlanta History Center Atlanta, Ga

VISITOR ATTRACTION CASE STUDY CYCLORAMA EXHIBIT - ATLANTA HISTORY CENTER ATLANTA, GA THE VISIONARIES CHOICE DIGITAL PROJECTION BRINGS THE PAST TO LIFE AT ATLANTA HISTORY CENTER For historians, researching the past and finding ties to the present is a cherished hobby, job, and duty. This is especially important when dealing with one-of-a- kind artifacts from critical moments in history. For the proud city of Atlanta, understanding and experiencing its past is not just for tourism; it is an integral part of the city’s identity and community. So, when the Atlanta History Center sought to create an engaging, larger-than-life experience for their gigantic Cyclorama exhibit, they relied on Digital Projection to tell the story of this precious painting and lead visitors on a journey back through time. Founded in 1926 to preserve and study the history of the city, the Atlanta Historical Society has spent decades collecting, researching, and publishing informa- tion about Atlanta and the surrounding areas. What began as a small, archival-focused group of historians, has now grown into one of the largest local history museums in the country; the Atlanta History Center – hosting exhibitions on the Civil War, Civil Rights Movement, literary masterpieces from Atlanta-born authors, and Native American culture. With four historic houses, 33 acres of curated gardens, and a multitude of wide-ranging programs and displays, it is one of the must-see tourist destinations in Atlanta. One of their key exhibits is the enormous and jaw-dropping Cyclorama. A HISTORIC MOMENT ON A MASSIVE SCALE Originally created in 1886, the 49ft tall by 371ft wide panoramic painting depicts the famous Battle of Atlanta; a critical moment in the Civil War. -

Susan Boardman -- on -- Gettysburg Cyclorama

Susan Boardman -- On -- Gettysburg Cyclorama The Civil War Roundtable of Chicago March 11, 2011, Chicago, Illinois by: Bruce Allardice ―What is a cyclorama?‖ is a frequent question heard in the visitor center at Gettysburg. In 1884, painter Paul Philippoteaux took brush to canvas to create an experience of gigantic proportion. On a 377-foot painting in the round, he recreated Pickett‘s Charge, the peak of fighting at the Battle of Gettysburg. Four versions were painted, two of which are among the last surviving cycloramas in the United States. When it was first displayed, the Gettysburg Cyclorama painting was so emotionally stirring that grown men openly wept. This was state-of- the-art entertainment for its time, likened to a modern IMAX theater. Today, restored to its original glory, the six ton behemoth is on display at the Gettysburg Museum and Visitor Center. On March 11, Sue Boardman will describe the genre of cycloramas in general and the American paintings in particular: Why they were made, who made them and how. She will then focus on the Gettysburg cycloramas with specific attention to the very first Chicago version and the one currently on display at the Gettysburg National Military Park (made for Boston). Sue Boardman, a Gettysburg Licensed Battlefield Guide since 2000, is a two-time recipient of the Superintendent‘s Award for Excellence in Guiding. Sue is a recognized expert of not only the Battle of Gettysburg but also the National Park‘s early history including the National Cemetery. Beginning in 2004, Sue served as historical consultant for the Gettysburg Foundation for the new museum project as well as for the massive project to conserve and restore the Gettysburg cyclorama. -

November Meeting the Other Cyclorama Sue Boardman Is a Native of Danville, Reservations Are Required Pennsylvania

Newsletter of the Civil War Round Table of Atlanta Founded 1949 November 2017 647th Meeting Leon McElveen, Editor November Meeting The Other Cyclorama Sue Boardman is a native of Danville, Reservations Are Required Pennsylvania. She graduated with honors from PLEASE MAIL IN YOUR DINNER Geisinger Medical Center School of Nursing and RESERVATION CHECK OF $36.00 PER Pennsylvania State University. Sue worked as an PERSON TO THE FOLLOWING ADDRESS: Emergency Room nurse for 23 years. In 2000, she became a Licensed Battlefield Guide and David Floyd received the Superintendent's Award for 4696 Kellogg Drive, SW Excellence in Guiding in 2005 and 2006. In 2002, Lilburn, GA 30047- 4408 Sue joined the Gettysburg Foundation's Museum TO REACH DAVID NO LATER THAN NOON Design Team during the project to build the new ON THE FRIDAY PRECEDING THE MEETING museum and visitor center complex. Reservations and payment may be made Sue served as research historian for the online at: cwrta.org Gettysburg Cyclorama conservation project. She authored the book The Battle of Gettysburg Date: Tuesday, November 14, 2017 Cyclorama: A History and Guide and The Gettysburg Cyclorama: The Turning Point of the Time: Cocktails: 5:30 pm Civil War on Canvas. Sue has also published the Dinner: 7:00 pm book Elizabeth Thorn: Wartime Caretaker of Place: Capital City Club - Downtown Gettysburg’s Evergreen Cemetery and several 7 John Portman Blvd. articles on the history of the American Civil War cycloramas. Price: $36.00 per person Don’t miss this chance to hear her compare and Program: Sue Boardman contrast two of the world’s great cycloramas, hers and ours. -

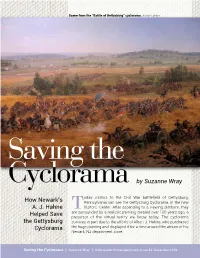

How Newark's A. J. Hahne Helped Save the Gettysburg Cyclorama By

Scene from the "Battle of Gettysburg" cyclorama. Author's photo by Suzanne Wray oday visitors to the Civil War battlefield of Gettysburg, How Newark’s Pennsylvania can see the Gettysburg Cyclorama, in the new A. J. Hahne TVisitors’ Center. After ascending to a viewing platform, they Helped Save are surrounded by a realistic painting created over 100 years ago, a precursor of the virtual reality we know today. The cyclorama the Gettysburg survives in part due to the efforts of Albert J. Hahne, who purchased Cyclorama the huge painting and displayed it for a time around the atrium of his Newark, NJ department store. Saving the Cyclorama | Suzanne Wray | www.GardenStateLegacy.com Issue 42 December 2018 Virtual reality and immersive environments are familiar concepts to most today, but less familiar are their precursors. These include the panorama, also called “cyclorama.” In the nineteenth century, viewers could immerse themselves in another world—a city, a landscape, a battlefield—by entering a purpose-built building, and climbing a spiral staircase to step onto a circular viewing platform. A circular painting, painted to be as realistic as possible, surrounded them. A three-dimensional foreground (the “faux terrain” or “diorama”) disguised the point at which the painting ended and the foreground began. The viewing platform hid the bottom of the painting, and an umbrella-shaped “vellum” hung from the roof, hiding the top of the painting and the skylights that admitted light to the building. Cut off from any reference to the outside world, viewers were immersed in the scene surrounding them, giving the sensation of “being there.”1 An Irish artist, Robert Barker (1739–1806), conceived the circular painting and patented the new art form on June 18, 1787. -

Yadegar Asisi Unveiled His Latest Panorama, TITANIC, on January 28Th, 2017 in the Panometer Leipzig in Germany

# 39 New Panoramas & Restoration Projects Panorama Updates & Related Formats Yadegar Asisi unveiled his latest panorama, TITANIC, on January 28th, 2017 in the Panometer Leipzig in Germany. March 4, 2017 - Panorama Challenge at the Queens Museum in Queens, New York. The Emergence of Pre-Cinema: Print Culture and the Optical Toy of the Literary September 29 - October 2, 2017 - 26th IPC Imagination, a new book by Alberto Gabriele. Conference at the Queens Museum in Queens, New York, USA. More details forthcoming. Hieratic Gaze, a 360 degree visual November 30 - December 2, 2017 - RE:TRACE the experience debuted at the Panorama Music 7th International Conference on the Histories of Media Festival in NYC. This year’s festival will include Art, Science and Technology in Vienna at Danube new works in a 360 dome theater, July 28-30. University. VLC 3.0 media player for Windows and Mac April 28 - 30, 2017 - 10th International Magic now features 360-degree video and photos. Lantern Society Convention in Birmingham, UK GAC Motor’s new GA8 luxury sedan includes a 360-degree visual imaging system. 39 Atlanta Cyclorama by Gordon Jones After years of discussion and intense planning, the time has arrived - the Battle of Atlanta painting is ready for the move from its nearly century-old home in Grant Park to the new custom-built 23,000- square-foot Lloyd and Mary Ann Whitaker Cyclorama Building at the Atlanta History Center. The painting is now successfully rolled onto two 45- foot-tall custom-built steel spools – weighing roughly 12,000 pounds each - that are standing inside the Grant Park Cyclorama building awaiting their move.