Holmes, Samuel 03-10-1986 Transrcipt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stumpf (Ella Ketcham Daggett) Papers, 1866, 1914-1992

Texas A&M University-San Antonio Digital Commons @ Texas A&M University-San Antonio Finding Aids: Guides to the Collection Archives & Special Collections 2020 Stumpf (Ella Ketcham Daggett) Papers, 1866, 1914-1992 DRT Collection at Texas A&M University-San Antonio Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tamusa.edu/findingaids Recommended Citation DRT Collection at Texas A&M University-San Antonio, "Stumpf (Ella Ketcham Daggett) Papers, 1866, 1914-1992" (2020). Finding Aids: Guides to the Collection. 160. https://digitalcommons.tamusa.edu/findingaids/160 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives & Special Collections at Digital Commons @ Texas A&M University-San Antonio. It has been accepted for inclusion in Finding Aids: Guides to the Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Texas A&M University-San Antonio. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ella Ketcham Daggett Stumpf Papers, 1866, 1914-1992 Descriptive Summary Creator: Stumpf, Ella Ketcham Daggett (1903-1993) Title: Ella Ketcham Daggett Stumpf Papers, 1866-1914-1992 Dates: 1866, 1914-1992 Creator Ella Ketcham Daggett was an active historic preservationist and writer Abstract: of various subjects, mainly Texas history and culture. Content Consisting primarily of short manuscripts and the source material Abstract: gathered in their production, the Ella Ketcham Daggett Stumpf Papers include information on a range of topics associated with Texas history and culture. Identification: Col 6744 Extent: 16 document and photograph boxes, 1 artifacts box, 2 oversize boxes, 1 oversize folder Language: Materials are in English Repository: DRT Collection at Texas A&M University-San Antonio Biographical Note A fifth-generation Texan, Ella Ketcham Daggett was born on October 11, 1903 at her grandmother’s home in Palestine, Texas to Fred D. -

TEXAS HERITAGE TRAIL Boy Scouts of America

Capitol Area Council TEXAS HERITAGE TRAIL Boy Scouts of America TRAIL REQUIREMENTS: 1. There should be at least one adult for each 10 hikers. A group must have an adult leader at all times on the trail. The Boy Scouts of America policy requires two adult leaders on all Scout trips and tours. 2. Groups should stay together while on the hike. (Large groups may be divided into several groups.) 3. Upon completion of the trail the group leader should send an Application for Trail Awards with the required fee for each hiker to the Capitol Area Council Center. (Only one patch for each participant.) The awards will be mailed or furnished as requested by the group leader. Note: All of Part One must be hiked and all points (1-15) must be visited. Part Two is optional. HIKER REQUIREMENTS: 1. Any registered member of the Boy Scouts of America, Girl Scouts, or other civic youth group may hike the trail. 2. Meet all Trail requirements while on the hike. 3. The correct Scout uniform should be worn while on the trail. Some article (T-shirt, armband, etc) should identify other groups. 4. Each hiker must visit the historical sites, participate in all of his/her group’s activities, and answer the “On the Trail Quiz” to the satisfaction of his/her leader. Other places of interest you may wish to visit are: Zilker Park and Barton Springs Barton Springs Road Elisabet Ney Museum 304 E. 34th. Street Hike and Bike Trail along Town Lake Camp Mabry 38th. Street Lake Travis FM #620 Lake Austin FM # 2222 Capitol Area Council TEXAS HERITAGE TRAIL Boy Scouts of America ACCOMODATIONS: McKinney Falls State Park, 5805 McKinney Falls Parkway, Austin, TX 78744, tel. -

Au Stin, Texas

A UN1ONN RAI LROAD S T A TION FOR AU STIN, TEXAS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER IN ARCHITECTURE at the Massa- chusette Institute of Technology, 1949 by Robert Bradford Newman B.A., University of Texas, 1938 M.A., University of Texas, 1939 2,,fptexR 19i49 William Wilson Wurster, Dean School of Architecture and Planning Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Massachusetts Dear Sir: In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Architecture, I respect- fully submit this report entitled, "A UNION RAILROAD STATION FOR AUSTIN, TEXAS". Yours vergy truly, Robert B. Newman Cambridge, Massachusetts 2 September 19T9 TABLE OF CONTENTS Austin - The City 3 Railroads in Austin, 1871 to Present 5 Some Proposed Solutions to the Railroad Problem 10 Specific Proposals of the Present Study 12 Program for Union Railroad Station 17 Bibliography 23 I ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am indebted to the members of the staff of the School of Architecture and Planning of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for their encouragement and helpful criticism in the completion of this study. Information regarding the present operations of the Missouri Pacific, Missouri Kansas and Texas, and Southern Pacific Railroads was furnished by officials of these lines. The City Plan Commission of Austin through its former Planning Supervisor, Mr. Glenn M. Dunkle, and through Mr. Charles Granger, Consultant to the Plan Commission gave encouragement to the pursuit of the present study and provided many of the street and topographic maps, aerial photographs and other information on existing and proposed railroad facilities. Without their help and consultation this study would have been most difficult. -

Northen Theatre , at the Original Nationally Renowned Arena Stage in Washington, D.C

~AUSTIN ·~7 ~ 11 -' SAVINGS £Qioabeth'g Your Institution of Higher Earning JEWELRY MOTOR INNS Compl ete Line of Jewelry Jewelry and Watch Repairs Chef Paul Kove ra prepares FACTORY AUTHORIZED (;picurean foods daily for your TIMEX ® pleasure. / Specia l orders pre pared when advance reservation s " Where Customers SE RVICE CENTER are made . Telephone : (512 ) Become Friends ." 476 -7 15 1. NORTHEN North THEATRE 7431 BUR NET ROA D RI CHCREE K PL AZA 11th & San Jacinto Playbill Austin, Texas 78701 South .:I'll. Jun e 17-29, 1974 112 EAST OL TORF CONTENTS T WIN OA KS SHOPPIN G CENTE R STRAIT 4 PERNELL ROBERTS MUSIC 6 TITL E PAGE EL RANCHO COMPANY 7 PROGRAM RESTAURANT No 1 8 PRODU CTION STAFF 302 E. 1st • 4 72- 18 14 9 CAST Fam ous for so m e of th e F inest Mexican Foods in t he Wo rld WHO' S WHO Mexican Style Sea Foo ds THE PIT PRODU CTION CREWS ~r908 N.Lamar Prepared with Shrimp Eating Out Is Fun - JO E JE FF GOLDBL ATT Also Steaks & Chicke n Especially at 'The Pit" Most Reco mmended Playb ill Editor Restaurant in Austin Food To Go ! By t h e Editor s of T IM E an d Life B oo k s • By MOBIL E TR AV EL Din ing Service ! GUI D E e By FLIGHT TIM E Co n ti n en Serving Beef, tal Air lin es Mag azin e e NEW Y OR K T IME S " Our F avorit e Mex ica n R esta u Sausage, Ham, Sp are Ribs, rant '' Distincti ve Fabrics For Your Creati ve Ideas - Chicken - Also A Co mpl ete ATE RI NG SE R VI E e Large Parkin g Area Cateri ng Availab le Richard J ones, Ow ner Typica l Mex ican Sty le S teak The Fabric Shop Carne Asa da Mixe d Phon e: 444 -2272 Drink s Dining Room Service Tw in Oaks EL RANCHO ~:r;~fh And Order s To Go Shopping Center RESTAURANTNol Locat io ns Op en 7 Day s 8ANKAMERICARQ. -

Thank You for Your Interest in Niweek 2004 Guest Activities. Attached You’Ll Find a Preliminary Schedule for Each Day of the Conference

Thank you for your interest in NIWeek 2004 guest activities. Attached you’ll find a preliminary schedule for each day of the conference. As in years past, we highly recommend you bring the following: • comfortable walking shoes • cool clothes • sunglasses • swimsuit • a hat that provides shade • towel We’ll take care of sunscreen, food, drinks, and so on. The guest fee is $200, which includes fees for guest tours and transportation from the Austin Convention Center to all of the attractions. The fee also includes lunch each day and passes to the NIWeek evening events held by National Instruments. If you would like to participate in any of the scheduled guest activities during NIWeek 2004, please register online at www.ni.com/niweek If you’re planning on spending additional time in the Austin area, feel free to talk with any of your guest hosts about attractions in the area that might interest you. If you want to plan in advance, you can find information on local weather, entertainment, recreation, shopping, and more at austin360.com or at austin.citysearch.com See you in August! Matt Jacobs National Instruments 11500 N Mopac Austin, TX 78759-3504 (512) 683-5728 [email protected] Preliminary Guest Activity Calendar Monday, August 16, 2004 Haunted Austin; Austin, Texas Your Hosts: Tia Garnett and Lisa Mounsif Rich in history, Austin is also rich in ghost lore. We start with a guided tour of the Texas State Cemetery to view the final resting places of Texas notables. Then we move on to the Neill-Cochran House, where the ghost of Colonel Neill has been seen riding his horse around the mansion; then onto the Driskill Hotel, where the ghost of Colonel Driskill is believed to haunt several of the guest rooms on the top floors of the hotel. -

November/December 2017

Page 1 of 19 Travis Audubon Board, Staff, and Committees: Officers President: Frances Cerbins Vice President: Mark Wilson Treasurer: Carol Ray Secretary: Julia Marsden Directors: Advisory Council: Karen Bartoletti J. David Bamberger Shelia Hargis Valarie Bristol Clif Ladd Victor Emanuel Suzanne Kho Sam Fason Sharon Richardson Bryan Hale Susan Rieff Karen Huber Virginia Rose Mary Kelly Eric Stager Andrew Sansom Jo Wilson Carter Smith Office Staff: Executive Director: Joan Marshall Director of Administration & Membership: Jordan Price Land Manager and Educator: Christopher Murray Chaetura Canyon Stewards: Paul & Georgean Kyle Program Assistant: Nancy Sprehn Education Manager: Erin Cord Design Director & Website Producer: Nora Chovanec Committees: Baker Core Team: Clif Ladd and Chris Murray Blair Woods Management: Mark Wilson Commons Ford: Shelia Hargis and Ed Fair Chaetura Canyon Management: Paul and Georgean Kyle Education: Cindy Cannon Field Trip: Dennis Palafox Hornsby Bend: Eric Stager Outreach/Member Meetings: Jane Tillman and Cindy Sperry Youth: Virginia Rose and Mary Kay Sexton Page 2 of 19 Avian Ink Contest Winners Announced SEPTEMBER 1, 2017 It was a packed house at Blue Owl Brewery’s tasting room last Friday as we unveiled Golden Cheeked Wild Barrel, an experimental new beer celebrating the Golden-cheeked Warbler. The crowd raised their glasses to this inspiring tiny songbird, an endangered Texas native currently fighting for continued protection under the Endangered Species Act. In honor of all the birds that inspire our lives, the crowd also toasted the winners of the Avian Ink Tattoo Contest. Five tattoos were selected for their creative depictions of birds in ink. The 1st place winner received a $100 Gift Certificate to Shanghai Kate’s Tattoo Parlor. -

Pka S&D 1954 Dec

* IIKA INITIATES! NOW YOU CAN WEAR A IIKA BADGE ORDERITTODAYFROM THIS OFFICIAL PRICE LIST - Sister Pin Min ia- or PLAIN ture No. 0 No. I No. 2 No. 3 Bevel Border - -------··-- $ 3.50 $ 5.25 $ 6.25 s 6.75 $ 9.00 Nugget, Chased or Engr aved Border --------------- ------ 4.00 5.75 6.75 7.25 10.50 FULL CROWN SET JEWELS No. 0 No. I 1'\o. 2 :-<o. 2'A! :~o . 3 Pearl Border --· $1 3.00 $1 5.00 $ 17 .50 $2 o. OO S24 .00 Pearl Border, Ruby or Sa pph ire Points -----· ····---------·-·····------ 14 .00 16.25 19.00 23.00 ~6.00 Pearl Border, Emerald Poin ts __ 16.00 18.00 2 1. 50 26.00 30.00 Pearl Border, D ia mo11d Po ints .. 2i.50 34 .75 45.75 59.75 72.75 Pearl and Sapphire Alternating ---------------------- 15.00 17 .50 20.75 25. 00 28 .00 Pearl and Ruby AhernatinJl ·------ 15.00 17.50 20.75 25 .00 28 .00 Pearl and Emerald Alternating _ 19.00 2 1.0V 25.50 31. 00 36.00 Pearl and D ia mond Alternating --·--·--------·-···- ····----- 41.50 53.75 72 .75 97.75 120.75 Diamond and Ruby or Sapph ire Alternating ------------------------- 43.50 56.25 76.00 10 1. 75 124.75 Diamond and Emerald Alternating ---· -----·-··------- 47.5 0 59.75 80.75 107.7 5 132 .75 Ruby or Sapphire Border -------- 17.00 19.75 24.00 29.00 32 .00 R uby or Sapphire Border, Diamond Points --------------- 30.50 38.5 0 50.75 65.7b 78 .75 Diamond Border ... -

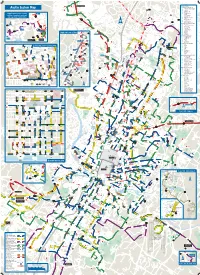

Austin System Map G 1L N

Leander Leander Park & Ride 983 986 987 183 S o u t h B e l l Bl vd 983 986 987 214 214 ne Blvd testo 1431 Whi r D n e re 214 rg e v E Main 214 St 1431 La ke li ne 214 B lv 983 Jonestown d Park & Ride 985 214 d el R ur a L 214 Bro nc o d R Bar-K anch L R n LeanderLeander Lago Vista HS Park & Ride 183 214 183 Rd ch Lakeline an Post Office 383 214 R K Co r- yo 983 987 Northwest a te B Tr 214 383 Park & Ride P a 214 383 s P 983 985 e e o d 985 983 985 987 c R 987 a d n e P d a r r k d V o lv a B F 214 B c l Lakeline v p a to n d es k a 383 a Mall L R d m Pace Bend h North Fork o Recreation Area L Plaza (LCRA-County) 1431 383 Forest North ES WalMart 983 1431 Lakeline Plaza 985 1 Jonestown 987 TOLL Park & Ride Target Lago Vista 214 Park & Ride D 183 aw Lakeline 214 n Rd Northwest Park & Ride ek ke Cre Routes 383, 983, 985 and 987 La Pkwy continue, see inset at left. Route Finder Grisham MS M i l Westwood HS l Local Service Routes (01-99) w 1 r i TOLL Austin System Map g 1L N. Lamar/S. Congress, via Lamar S Lago Vista h ho Anderson t r 1M N. -

NOVEMBER 3 - 7, 2001 AUSTIN OMNI HOTEL DOWNTOWN Austin Trivia: AUSTIN, TEXAS L.B.J

NAALJ 2001 ANNUAL MEETING AND CONFERENCE NOVEMBER 3 - 7, 2001 AUSTIN OMNI HOTEL DOWNTOWN Austin Trivia: AUSTIN, TEXAS L.B.J. proposed to Lady Bird on their first Registration Form (one form per person; please photocopy) date, over breakfast at the Driskill Hotel . The Driskill later was used as election night headquar- NAME:_____________________________________________________ TITLE: _____________________________________________________ ters. The L.B.J. Library is free and open every day except AGENCY/COMPANY: ________________________________________ Christmas, at Johnson’s request. DAYTIME PHONE NUMBER: _________________________________ NAALJ FAX NUMBER:______________________________________________ ADDRESS: _________________________________________________ CITY/STATE/ZIP: ____________________________________________ North America’s largest urban bat colony has made the EMAIL ADDRESS:___________________________________________ underside of the Congress Avenue bridge their summer SPOUSE/GUEST NAME:______________________________________ Registration includes Monday luncheon, Monday evening reception at the State Museum, home. Arriving in mid-March and returning to their win- Tuesday evening banquet and course materials. ter home in Mexico by November, the 1.5 million free-tail Entree choice for banquet (please check one) 1. Free Range chicken 2. Grilled Mahi Mahi 3. Vegetarian Plate bats consume between 10,000 and 30,000 pounds of insects FEES AMOUNT DUE a night. Today, the bats are one of Austin’s most popular 2001 Registration fee . .$350.00 CONFERENCE NAALJ Member Discount . .-$25.00 tourist attractions, generating nearly 8 million dollars in Early Discount (before 9/3/01) . .-$25.00 Late Registration (after 10/19/01 or at door) . .+$ 25.00 yearly revenue. Guest/spouse (Luncheon, reception and banquet only) Banquet entree 1 2 3 (circle one) . .+$105.00 Additional: Luncheon $25.00 ea. -

I 3 Inbu Deeigebe 6

GEORGE WASHINGTON LITTLEFIELD A Texa n a n d His $ n iver sity T H E $ NI$ E $ S I T$ $ $ TE $ A S W A S I N I T S I N fancy when $ a $or George Washington Lit tl efiel d , joined by other men of vision , breathed into it the vitality essential to its Littl efiel d early development . was a staunch supporter of education who invested himself and his wealth in the future of The University of Texas . His devotion to the University has had an incalculable and ever-increas ing in flu ence upon the state . It would not be possible to tell the story of The Univers ity of Texas without telling the it l fi l o L t e e d . story of Ge rge W . Any account of the institution or of the man ’ must inevitably involve the story of one man s association with the in stitu tion of learning he loved . Littl efiel d . Major was aptly described by his friend , Judge Nelson W Phil “ a t Littl efie l d as m a n f lips , the dedication of Alice Dormitory a unaf ected and unstudied , Spartan in the ruggedness and directness of his character . He cared nothing for eulogy or praise . He never sought distinction or public honors . What he accomplished in every phase of his life , he earned . What he valued most in men was simple sincerity and steadfastness of conviction . L $ $ A i $ na 30x24 n c h es . E$ T $ OO N O E$ L ITTL E $ IE L D by DON L D W EI S $ A N N $ l . -

A Ustin , Texas

PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS $26.95 austin, texas austin, Austin, Texas Austin,PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS Texas PUBLISHERS A Photographic Portrait Since its founding in 1839, Austin Peter Tsai A Photographic Portrait has seen quite a bit of transformation Peter Tsai is an internationally published over the years. What was once a tiny photographer who proudly calls Austin, frontier town is today a sophisticated Texas his home. Since moving to Austin urban area that has managed to main- in 2002, he has embraced the city’s natu- PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTStain its distinctive,PUBLISHERS offbeat character, ral beauty, its relaxed and open-minded and indeed, proudly celebrates it. attitude, vibrant nightlife, and creative The city of Austin was named for communities. In his Austin photos, he Stephen F. Austin, who helped to settle strives to capture the spirit of the city the state of Texas. Known as the “Live he loves by showcasing its unique and A P Music Capital of the World,” Austin har- eclectic attractions. H bors a diverse, well-educated, creative, Although a camera is never too far O PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS and industrious populace. Combined T away, when he is not behind the lens, OGR with a world-class public university, you can find Peter enjoying Austin with APH a thriving high-tech industry, and a his friends, exploring the globe, kicking laid-back, welcoming attitude, it’s no a soccer ball, or expanding his culinary IC POR wonder Austin’s growth continues un- palate. abated. To see more of Peter’s photography, visit T From the bracing artesian springs to R www.petertsaiphotography.com and fol- PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTSA PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS I the white limestone cliffs and sparkling low him on Twitter @supertsai. -

Local Texas Bridges

TEXAS DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION Environmental Affairs Division, Historical Studies Branch Historical Studies Report No. 2004-01 A Guide to the Research and Documentation of Local Texas Bridges By Lila Knight, Knight & Associates A Guide to the Research and Documentation of Local Texas Bridges January 2004 Revised October 2013 Submitted to Texas Department of Transportation Environmental Affairs Division, Historical Studies Branch Work Authorization 572-06-SH002 (2004) Work Authorization 572-02-SH001 (2013) Prepared by Lila Knight, Principal Investigator Knight & Associates PO Box 1990 Kyle, Texas 78640 A Guide to the Research and Documentation of Local Texas Bridges Copyright© 2004, 2013 by the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) All rights reserved. TxDOT owns all rights, title, and interest in and to all data and other information developed for this project. Brief passages from this publication may be reproduced without permission provided that credit is given to TxDOT and the author. Permission to reprint an entire chapter or section, photographs, illustrations and maps must be obtained in advance from the Supervisor of the Historical Studies Branch, Environmental Affairs Division, Texas Department of Transportation, 118 East Riverside Drive, Austin, Texas, 78704. Copies of this publication have been deposited with the Texas State Library in compliance with the State Depository requirements. For further information on this and other TxDOT historical publications, please contact: Texas Department of Transportation Environmental Affairs Division Historical Studies Branch Bruce Jensen, Supervisor Historical Studies Report No. 2004-01 By Lila Knight Knight & Associates Table of Contents Introduction to the Guide. 1 A Brief History of Bridges in Texas. 2 The Importance of Research.