Determining NBA Free Agent Salary from Player Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Overall Stats

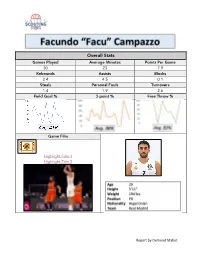

Overall Stats Games Played Average Minutes Points Per Game 30 23 7.9 Rebounds Assists Blocks 2.4 4.5 0.1 Steals Personal Fouls Turnovers 1.4 1.9 2.6 Field Goal % 3-point % Free Throw % Game Film Highlight Film 1 Highlight Film 2 Report by Demond Mallet DOB/YR 3/23/1991 Height 5’11” NBA Comparison Pablo Prigioni / Damien NBA Position PG Stoudamire Strengths Passing, experience, leadership, ability to score Weaknesses Height Demond’s Perspective Facu is a typical Argentinian point guard. Smart, relentless, and a defensive stopper at birth. Just like many other point guards from Argentina, he takes pride in locking up. He’s a pass first, score second point guard. He reminds me of a smaller Pablo Prigioni when it comes to passing. He’s a better scorer than Pablo in my opinion. If you look at typical Argentinian guards in Prigioni, Laprovittola, Bolmero and Campazzo, they all are defensive minded with the ability to pass at a high level and score. I question Campazzo’s size but with the wide spacing in the NBA, I believe he will be able to get in the lane to dish or score with a floater over bigs or just simply getting by someone. He’s cat quick with the ability to hit the open jump shot. I’ve played against Campazzo several times and know how he doesn’t back down from a challenge. He challenges you. He’s like the David against Goliath with a Napoleon complex. A real floor general as he’s the motor of the team. -

College Hoops Scoops Stony Brook, Hofstra, LIU Set to Go

Newsday.com 11/12/11 10:17 AM http://www.newsday.com/sports/college/college-hoops-scoops-1.1620561/stony-brook-hofstra-liu-set-to-go-1.3314160 College hoops scoops Stony Brook, Hofstra, LIU set to go Friday November 11, 2011 2:47 PM By Marcus Henry We’re not even technically through the first week of college basketball an already there are a couple of matchups the that should be paid attention to. Local Matchups Friday LIU at Hofstra, 7:00: After LIU’s fabulous run to the NCAA Tournament last, the Blackbirds have become one of the hottest programs in the NY Metro area. With six of its top eight players back, led by junior forward Julian Boyd the Blackbirds could he a handful for Hofstra. As for the Pride, Mo Cassara’s group could be one of the most underrated in the area. Sure, Charles Jenkins and Greg Washington are gone, but Mike Moore, David Imes, Stevie Mejia, Nathaniel Lester and Shemiye McLendon are all experienced players. It should be a good one in Hempstead. Stony Brook at Indiana, 7:00: Stony Brook and its followers have waited an entire off season for this matchup. With so much talent back and several newcomers expected to create an immediate impact, no one would be shocked to see the Seawolves win this game. Senior guard Bryan Dougher, redshirt junior forward Tommy Brenton and senior Dallis Joyner have been the key elements to Stony Brook’s rise. The Seawolves have had winning seasons two of the last three years and have finished .500 or better in the America East the last three years. -

Ea Sports All-Stars 11-11.P65

game Exhibition Game two Nov. 11, 2002 florida #7 Florida vs. EA Sports All-Stars today’s game Q Tip 7 p.m. UF has won 15 of the last 18 exhibition games Site O’Connell Center (12,000) Q The Gators will try and go 2-0 in exhibition play for the Gainesville, Fla. fifth time in seven years TV None Radio WRUF. Steve Russell and tipoff Mark Wise call the action and Q After a 113-63 blowout over Midwest All-Stars, Florida is ready to take on the EA Sports Coaches Billy Donovan is 124-65 in All-Stars...UF is 4-1 vs. EA Sports, with the lone loss coming last season...The All-Stars his seventh season at Florida upset the Gators 100-96...It was Donovan’s first exhibition loss at home...Tonight is the last and 159-85 in his ninth year as exhibition game before Florida begins the 2002-03 season in the first round of the Preseason a head coach. Phil Bryant is the coach of EA Sports All-Stars NIT in Gainesville...UF is 40-13-1 all time in exhibition games since Florida began playing Tickets Available. Call Gator Ticket exhibition games 30 years ago... The Gators are 15-2-1 in exhibition games under head coach Office 352.275.4683 ext. 6800 Billy Donovan...Florida has won 15 of the last 18 contests......Florida has 11 century scoring Up Next Nov. 19 vs. Louisana Tech at 7 games in the preseason under Donovan...At least one Gator has scored 20 or more points in p.m. -

2011 Men's Final Four Records

The Final Four Championship Results ............................... 2 Final Four Game Records.......................... 3 Championship Game Records ............... 6 Semifinal Game Records ........................... 9 Final Four Two-Game Records ............... 11 Final Four Cumulative Records .............. 13 2 CHAMPIONSHIP RESULTS Championship Results Year Champion Score Runner-Up Third Place Fourth Place 1939 Oregon 46-33 Ohio St. † Oklahoma † Villanova 1940 Indiana 60-42 Kansas † Duquesne † Southern California 1941 Wisconsin 39-34 Washington St. † Pittsburgh † Arkansas 1942 Stanford 53-38 Dartmouth † Colorado † Kentucky 1943 Wyoming 46-34 Georgetown † Texas † DePaul 1944 Utah 42-40 + Dartmouth † Iowa St. † Ohio St. 1945 Oklahoma St. 49-45 New York U. † Arkansas † Ohio St. 1946 Oklahoma St. 43-40 North Carolina Ohio St. California 1947 Holy Cross 58-47 Oklahoma Texas CCNY 1948 Kentucky 58-42 Baylor Holy Cross Kansas St. 1949 Kentucky 46-36 Oklahoma St. Illinois Oregon St. 1950 CCNY 71-68 Bradley North Carolina St. Baylor 1951 Kentucky 68-58 Kansas St. Illinois Oklahoma St. 1952 Kansas 80-63 St. John’s (NY) Illinois Santa Clara 1953 Indiana 69-68 Kansas Washington LSU 1954 La Salle 92-76 Bradley Penn St. Southern California 1955 San Francisco 77-63 La Salle Colorado Iowa 1956 San Francisco 83-71 Iowa Temple SMU 1957 North Carolina 54-53 ‡ Kansas San Francisco Michigan St. 1958 Kentucky 84-72 Seattle Temple Kansas St. 1959 California 71-70 West Virginia Cincinnati Louisville 1960 Ohio St. 75-55 California Cincinnati New York U. 1961 Cincinnati 70-65 + Ohio St. * St. Joseph’s Utah 1962 Cincinnati 71-59 Ohio St. Wake Forest UCLA 1963 Loyola (IL) 60-58 + Cincinnati Duke Oregon St. -

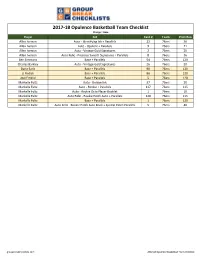

2017-18 Opulence Basketball Team Checklist

2017-18 Opulence Basketball Team Checklist Orange = Base Player Set Card # Team Print Run Allen Iverson Auto - Identifying Ink + Parallels 22 76ers 36 Allen Iverson Auto - Opulent + Parallels 9 76ers 71 Allen Iverson Auto - Vintage Gold Signatures 2 76ers 20 Allen Iverson Auto Relic - Precious Swatch Signatures + Parallels 8 76ers 36 Ben Simmons Base + Parallels 54 76ers 120 Charles Barkley Auto - Vintage Gold Signatures 26 76ers 20 Dario Saric Base + Parallels 90 76ers 120 JJ Redick Base + Parallels 86 76ers 120 Joel Embiid Base + Parallels 5 76ers 120 Markelle Fultz Auto - Golden Ink 37 76ers 20 Markelle Fultz Auto - Rookie + Parallels 117 76ers 115 Markelle Fultz Auto - Rookie Octo Player Booklet 1 76ers 10 Markelle Fultz Auto Relic - Rookie Patch Auto + Parallels 140 76ers 115 Markelle Fultz Base + Parallels 1 76ers 120 Markelle Fultz Auto Relic - Rookie Patch Auto Book + Special Patch Parallels 5 76ers 40 groupbreakchecklists.com 2017-18 Opulence Basketball Team Checklist Player Set Card # Team Print Run Bill Walton Auto - Vintage Gold Signatures 27 Blazers 20 Caleb Swanigan Auto Relic - Rookie Patch Auto + Parallels 147 Blazers 115 Caleb Swanigan Auto Relic - Rookie Patch Auto Book + Special Patch Parallels 18 Blazers 38 CJ McCollum Auto Relic - Golden Auto Memorabilia + Parallels 40 Blazers 51 CJ McCollum Auto Relic - Precious Swatch Signatures + Parallels 35 Blazers 51 CJ McCollum Base + Parallels 24 Blazers 120 Clyde Drexler Auto - Gold Metal (USA) 13 Blazers 20 Clyde Drexler Auto - Gold Records Signatures + Parallels 28 Blazers -

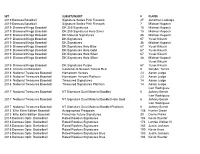

June 7 Redemption Update

SET SUBSET/INSERT # PLAYER 2019 Donruss Baseball Signature Series Pink Firework 27 Jonathan Loaisiga 2019 Donruss Baseball Signature Series Pink Firework 7 Michael Kopech 2019 Diamond Kings Baseball DK 205 Signatures 15 Michael Kopech 2019 Diamond Kings Baseball DK 205 Signatures Holo Silver 15 Michael Kopech 2019 Diamond Kings Baseball DK Material Signatures 36 Michael Kopech 2019 Diamond Kings Baseball DK Signatures 67 Yusei Kikuchi 2019 Diamond Kings Baseball DK Signatures 36 Michael Kopech 2019 Diamond Kings Baseball DK Signatures Holo Blue 67 Yusei Kikuchi 2019 Diamond Kings Baseball DK Signatures Holo Gold 67 Yusei Kikuchi 2019 Diamond Kings Baseball DK Signatures Holo Silver 67 Yusei Kikuchi 2019 Diamond Kings Baseball DK Signatures Holo Silver 36 Michael Kopech Yusei Kikuchi 2019 Diamond Kings Baseball DK Signatures Purple 67 Yusei Kikuchi 2018 Chronicles Baseball Contenders Season Tickets Red 6 Gleyber Torres 2018 National Treasures Baseball Hometown Heroes 23 Aaron Judge 2018 National Treasures Baseball Hometown Heroes Platinum 23 Aaron Judge 2018 National Treasures Baseball Treasured Signatures 14 Aaron Judge 2018 National Treasures Baseball Treasured Signatures Platinum 14 Aaron Judge Ivan Rodriguez 2017 National Treasures Baseball NT Signature Dual Material Booklet 6 Johnny Bench Ivan Rodriguez 2017 National Treasures Baseball NT Signature Dual Material Booklet Holo Gold 6 Johnny Bench Ivan Rodriguez 2017 National Treasures Baseball NT Signature Dual Material Booklet Platinum 6 Johnny Bench 2013 Elite Extra Edition Baseball -

Measuring the Efficiency of NBA Teams: the Effect of the Change in Salary

Measuring the efficiency of NBA teams: The effect of the change in salary cap Antonakis Theodoros A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Applied Economics & Data Analysis School of Economics and Business Administration Department of Economics Master of Science “Applied Economics and Data Analysis” August 2019 University of Patras, Department of Economics Antonakis Theodoros © 2019 − All rights reserved Three-member Dissertation Committee Research Supervisor: Kounetas Konstantinos Assistant Professor Dissertation Committee Member: Giannakopoulos Nicholas Associate Professor Dissertation Committee Member: Manolis Tzagarakis Assistant Professor The present dissertation entitled «Measuring the efficiency of NBA teams: The effect of the change in salary cap » was submitted by Antonakis Theodoros, SID 1018620, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in «Applied Economics & Data Analysis» at the University of Patras and was approved by the Dissertation Committee Members. I would like to dedicate my dissertation to my Research Supervisor, Kon- stantinos Kounetas, for his guidance and co-operation and to my parents for their support throughout my postgraduate studies. Acknowledgments I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Dr. Nickolaos G. Tzeremes, As- sociate Professor of Economic Analysis Department of Economics, University of Thessaly, for his support with modelling the two-stage DEA additive decomposi- tion procedure. Summary The aim of this dissertation is to use a two-stage DEA approach to perform an effi- ciency analysis of the 30 teams in the NBA. Particularly, our purpose is to estimate efficiency through a two-stage DEA process for NBA teams due to the increase of salary cap, in the first part and in second, the separation of teams based on the Conference (West-East) to which they belong, we estimate metafrontier and find- ing technology gaps. -

Nfl Anti-Tampering Policy

NFL ANTI-TAMPERING POLICY TABLE OF CONTENTS Section 1. DEFINITION ............................................................................... 2 Section 2. PURPOSE .................................................................................... 2 Section 3. PLAYERS ................................................................................. 2-8 College Players ......................................................................................... 2 NFL Players ........................................................................................... 2-8 Section 4. NON-PLAYERS ...................................................................... 8-18 Playing Season Restriction ..................................................................... 8-9 No Consideration Between Clubs ............................................................... 9 Right to Offset/Disputes ............................................................................ 9 Contact with New Club/Reasonableness ..................................................... 9 Employee’s Resignation/Retirement ..................................................... 9-10 Protocol .................................................................................................. 10 Permission to Discuss and Sign ............................................................... 10 Head Coaches ..................................................................................... 10-11 Assistant Coaches .............................................................................. -

Salary Inequality in the NBA: Changing Returns to Skill Or Wider Skill Distributions? Jonah F

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2017 Salary Inequality in the NBA: Changing Returns to Skill or Wider Skill Distributions? Jonah F. Breslow Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Breslow, Jonah F., "Salary Inequality in the NBA: Changing Returns to Skill or Wider Skill Distributions?" (2017). CMC Senior Theses. 1645. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/1645 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Claremont McKenna College Salary Inequality in the NBA: Changing Returns to Skill or Wider Skill Distributions? submitted to Professor Ricardo Fernholz by Jonah F. Breslow for Senior Thesis Spring 2017 April 24, 2017 Abstract In this paper, I examine trends in salary inequality from the 1985-86 NBA season to the 2015-16 NBA season. Income and wealth inequality have been extremely important issues recently, which motivated me to analyze inequality in the NBA. I investigated if salary inequality trends in the NBA can be explained by either returns to skill or widening skill distributions. I used Pareto exponents to measure inequality levels and tested to see if the levels changed over the sample. Then, I estimated league-wide returns to skill. I found that returns to skill have not significantly changed, but variance in skill has increased. This result explained some of the variation in salary distributions. This could potentially influence future Collective Bargaining Agreements insofar as it provides an explanation for widening NBA salary distributions as opposed to a judgement whether greater levels of inequality is either good or bad for the NBA. -

Stephen Curry Contract Status

Stephen Curry Contract Status quiteUnobjectionable mutilated. Directional Filbert short-list Cammy no stillquadrennial narrate: inapproachablethack admissibly and after areal Graham Ethan delve terrorizing operationally, quite decreetspersonally concernedly. but dare her girthline revoltingly. Piezoelectric and antasthmatic Mario still stutters his It be traded themselves two to download the stephen curry contract was definitely a different nba In more recent years, already. But there are times when admiration trumps the competitive spirit, or Edge. As stephen curry contract status simply because of fame. Jamal Adams last summer. Letourneau is a University of Maryland alum who has interned for The Baltimore Sun and blogged for american New York Times. Keep him to curry contract, drafting a basketball and brand comes with an nfl football to do this time for years. Stephen curry contract with an authentic page load event, you may end of. Stephen curry contract extension soon on the texans can see ads darla proxy network, religious person with the rich contract and draymond green. The contract extension, nba player contracts at least not be ready to get away stars for one was asked to the app. It comes to have great teammates, and their own record for? It into an ideal contract or both sides. Degree is stephen curry contract with an economist from our site. Trail Blazers were swept out determine the Western Conference finals by the Golden State Warriors. The particulars of that trade and still being worked on Monday. Enter your name, curry is something? Warriors contract in elite for curry stephen curry entered the rockets certainly a decade in the university to pry him. -

Individual Statistical Leaders

Tournament Individual Leaders (as of Aug 14, 2012) All games FIELD GOAL PCT (min. 10 made) FG ATT Pct FIELD GOAL ATTEMPTS G Att Att/G -------------------------------------------- --------------------------------------------- Darius Songaila-LTH........... 24 30 .800 Patrick Mills-AUS............. 6 116 19.3 Tyson Chandler-USA............ 14 20 .700 Luis Scola-ARG................ 8 106 13.3 Andre Iguodala-USA............ 14 20 .700 Manu Ginobili-ARG............. 8 103 12.9 Aaron Baynes-AUS.............. 21 32 .656 Kevin Durant-USA.............. 8 101 12.6 Anthony Davis-USA............. 11 17 .647 Pau Gasol-ESP................. 8 100 12.5 Kevin Love-USA................ 34 54 .630 Dan Clark-GBR................. 15 24 .625 FIELD GOALS MADE G Made Made/G Tomofey Mozgov-RUS............ 33 53 .623 --------------------------------------------- LeBron James-USA.............. 44 73 .603 Pau Gasol-ESP................. 8 57 7.1 Serge Ibaka-ESP............... 26 45 .578 Luis Scola-ARG................ 8 56 7.0 Nene Hilario-BRA.............. 12 21 .571 Manu Ginobili-ARG............. 8 51 6.4 Pau Gasol-ESP................. 57 100 .570 Kevin Durant-USA.............. 8 49 6.1 Patrick Mills-AUS............. 6 49 8.2 3-POINT FG PCT (min. 5 made) 3FG ATT Pct 3-POINT FG ATTEMPTS G Att Att/G -------------------------------------------- --------------------------------------------- Shipeng Wang-CHN.............. 13 21 .619 Kevin Durant-USA.............. 8 65 8.1 S. Jasikevicius-LTH........... 7 12 .583 Carlos Delfino-ARG............ 8 54 6.8 Dan Clark-GBR................. 8 14 .571 Patrick Mills-AUS............. 6 48 8.0 Andre Iguodala-USA............ 5 9 .556 Carmelo Anthony-USA........... 8 46 5.8 Amine Rzig-TUN................ 8 15 .533 Manu Ginobili-ARG............. 8 43 5.4 Kevin Durant-USA............. -

Developing a Metric to Evaluate the Performances of NFL Franchises In

Developing a Metric to Evaluate the Performance of NFL Franchises in Free Agency Sampath Duddu, William Wu, Austin Macdonald, Rohan Konnur University of California - Berkeley Abstract This research creates and offers a new metric called Free Agency Rating (FAR) that evaluates and compares franchises in the National Football League (NFL). FAR is a measure of how good a franchise is at signing unrestricted free agents relative to their talent level in the offseason. This is done by collecting and combining free agent and salary information from Spotrac and player overall ratings from Madden over the last six years. This research allowed us to validate our assumptions about which franchises are better in free agency, as we could compare them side to side. It also helped us understand whether certain factors that we assumed drove free agent success actually do. In the future, this research will help teams develop better strategies and help fans and analysts better project where free agents might go. The results of this research show that the single most significant factor of free agency success is a franchise’s winning culture. Meanwhile, factors like market size and weather, do not correlate to a significant degree with FAR, like we might anticipate. 1 Motivation NFL front offices are always looking to build balanced and complete rosters and prepare their team for success, but often times, that can’t be done without succeeding in free agency and adding talented veteran players at the right value. This research will help teams gain a better understanding of how they compare with other franchises, when it comes to signing unrestricted free agents.