Return to the Grindhouse: Tarantino and the Modernization of 1970S Exploitation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

H K a N D C U L T F I L M N E W S

More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In H K A N D C U L T F I L M N E W S H K A N D C U LT F I L M N E W S ' S FA N B O X W E L C O M E ! HK and Cult Film News on Facebook I just wanted to welcome all of you to Hong Kong and Cult Film News. If you have any questions or comments M O N D AY, D E C E M B E R 4 , 2 0 1 7 feel free to email us at "SURGE OF POWER: REVENGE OF THE [email protected] SEQUEL" Brings Cinema's First Out Gay Superhero Back to Theaters in January B L O G A R C H I V E ▼ 2017 (471) ▼ December (34) "MORTAL ENGINES" New Peter Jackson Sci-Fi Epic -- ... AND NOW THE SCREAMING STARTS -- Blu-ray Review by ... ASYLUM -- Blu-ray Review by Porfle She Demons Dance to "I Eat Cannibals" (Toto Coelo)... Presenting -- The JOHN WAYNE/ "GREEN BERETS" Lunch... Gravitas Ventures "THE BILL MURRAY EXPERIENCE"-- i... NUTCRACKER, THE MOTION PICTURE -- DVD Review by Po... John Wayne: The Crooning Cowpoke "EXTRAORDINARY MISSION" From the Writer of "The De... "MOLLY'S GAME" True High- Stakes Poker Thriller In ... Surge of Power: Revenge of the Sequel Hits Theaters "SHOCK WAVE" With Andy Lau Cinema's First Out Gay Superhero Faces His Greatest -- China’s #1 Box Offic... Challenge Hollywood Legends Face Off in a New Star-Packed Adventure Modern Vehicle Blooper in Nationwide Rollout Begins in January 2018 "SHANE" (1953) "ANNIHILATION" Sci-Fi "A must-see for fans of the TV Avengers, the Fantastic Four Thriller With Natalie and the Hulk" -- Buzzfeed Portma.. -

Quentin Tarantino's KILL BILL: VOL

Presents QUENTIN TARANTINO’S DEATH PROOF Only at the Grindhouse Final Production Notes as of 5/15/07 International Press Contacts: PREMIER PR (CANNES FILM FESTIVAL) THE WEINSTEIN COMPANY Matthew Sanders / Emma Robinson Jill DiRaffaele Villa Ste Hélène 5700 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 600 45, Bd d’Alsace Los Angeles, CA 90036 06400 Cannes Tel: 323 207 3092 Tel: +33 493 99 03 02 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] From the longtime collaborators (FROM DUSK TILL DAWN, FOUR ROOMS, SIN CITY), two of the most renowned filmmakers this summer present two original, complete grindhouse films packed to the gills with guns and guts. Quentin Tarantino’s DEATH PROOF is a white knuckle ride behind the wheel of a psycho serial killer’s roving, revving, racing death machine. Robert Rodriguez’s PLANET TERROR is a heart-pounding trip to a town ravaged by a mysterious plague. Inspired by the unique distribution of independent horror classics of the sixties and seventies, these are two shockingly bold features replete with missing reels and plenty of exploitative mayhem. The impetus for grindhouse films began in the US during a time before the multiplex and state-of- the-art home theaters ruled the movie-going experience. The origins of the term “Grindhouse” are fuzzy: some cite the types of films shown (as in “Bump-and-Grind”) in run down former movie palaces; others point to a method of presentation -- movies were “grinded out” in ancient projectors one after another. Frequently, the movies were grouped by exploitation subgenre. Splatter, slasher, sexploitation, blaxploitation, cannibal and mondo movies would be grouped together and shown with graphic trailers. -

Appalling! Terrifying! Wonderful! Blaxploitation and the Cinematic Image of the South

Antoni Górny Appalling! Terrifying! Wonderful! Blaxploitation and the Cinematic Image of the South Abstract: The so-called blaxploitation genre – a brand of 1970s film-making designed to engage young Black urban viewers – has become synonymous with channeling the political energy of Black Power into larger-than-life Black characters beating “the [White] Man” in real-life urban settings. In spite of their urban focus, however, blaxploitation films repeatedly referenced an idea of the South whose origins lie in antebellum abolitionist propaganda. Developed across the history of American film, this idea became entangled in the post-war era with the Civil Rights struggle by way of the “race problem” film, which identified the South as “racist country,” the privileged site of “racial” injustice as social pathology.1 Recently revived in the widely acclaimed works of Quentin Tarantino (Django Unchained) and Steve McQueen (12 Years a Slave), the two modes of depicting the South put forth in blaxploitation and the “race problem” film continue to hold sway to this day. Yet, while the latter remains indelibly linked, even in this revised perspective, to the abolitionist vision of emancipation as the result of a struggle between idealized, plaintive Blacks and pathological, racist Whites, blaxploitation’s troping of the South as the fulfillment of grotesque White “racial” fantasies offers a more powerful and transformative means of addressing America’s “race problem.” Keywords: blaxploitation, American film, race and racism, slavery, abolitionism The year 2013 was a momentous one for “racial” imagery in Hollywood films. Around the turn of the year, Quentin Tarantino released Django Unchained, a sardonic action- film fantasy about an African slave winning back freedom – and his wife – from the hands of White slave-owners in the antebellum Deep South. -

“No Reason to Be Seen”: Cinema, Exploitation, and the Political

“No Reason to Be Seen”: Cinema, Exploitation, and the Political by Gordon Sullivan B.A., University of Central Florida, 2004 M.A., North Carolina State University, 2007 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2017 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Gordon Sullivan It was defended on October 20, 2017 and approved by Marcia Landy, Distinguished Professor, Department of English Jennifer Waldron, Associate Professor, Department of English Daniel Morgan, Associate Professor, Department of Cinema and Media Studies, University of Chicago Dissertation Advisor: Adam Lowenstein, Professor, Department of English ii Copyright © by Gordon Sullivan 2017 iii “NO REASON TO BE SEEN”: CINEMA, EXPLOITATION, AND THE POLITICAL Gordon Sullivan, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2017 This dissertation argues that we can best understand exploitation films as a mode of political cinema. Following the work of Peter Brooks on melodrama, the exploitation film is a mode concerned with spectacular violence and its relationship to the political, as defined by French philosopher Jacques Rancière. For Rancière, the political is an “intervention into the visible and sayable,” where members of a community who are otherwise uncounted come to be seen as part of the community through a “redistribution of the sensible.” This aesthetic rupture allows the demands of the formerly-invisible to be seen and considered. We can see this operation at work in the exploitation film, and by investigating a series of exploitation auteurs, we can augment our understanding of what Rancière means by the political. -

Baadassss Gangstas: the Parallel Influences, Characteristics and Criticisms of the Blaxploitation Cinema and Gangsta Rap Movements

Baadassss Gangstas: The Parallel Influences, Characteristics and Criticisms of the Blaxploitation Cinema and Gangsta Rap Movements Dustin Engels Journal of Hip Hop Studies, Volume 1, Issue 1, Spring 2014, pp. 62 ‐ 80 BAADASSS GANGSTAS . Baadassss Gangstas: The Parallel Influences, Characteristics and Criticisms of the Blaxploitation Cinema and Gangsta Rap Movements Dustin Engels Abstract Serving as two of the most visible African American cultural movements, blaxploitation cinema and gangsta rap played essential roles in giving African American artists an outlet to establish a new black identity for mainstream audiences. After exploring the similarities between the cultural and economic conditions that spawned both movements, this essay examines the parallel techniques by which the preeminent entries in both genres established themselves as culturally relevant for African American audiences. These techniques included a reliance on place and space to establish authenticity, as well as employing African American myths and folklore such as the Signifying Monkey and the badman. By establishing themselves as mainstream representations of black identity, the harshest critics and staunchest defenders of both movements came from within the African American community, a clear indication of the important role each would play in establishing a new era of black representation in popular culture. In October 2012, New Orleans rapper Curren$y released a mixtape online for his fans entitled Priest Andretti. Taking its name from the main character of the 1972 blaxploitation film Super Fly, this fourteen-track mixtape frequently pays homage to the blaxploitation movement that occurred in the early 1970s by incorporating clips from Super Fly throughout, as well as including songs entitled “Max Julien” (star of the 1973 film The Mack) and “Cleopatra Jones” (title character of the 1973 film Cleopatra Jones). -

Crash- Amundo

Stress Free - The Sentinel Sedation Dentistry George Blashford, DMD tvweek 35 Westminster Dr. Carlisle (717) 243-2372 www.blashforddentistry.com January 19 - 25, 2019 Don Cheadle and Andrew Crash- Rannells star in “Black Monday” amundo COVER STORY .................................................................................................................2 VIDEO RELEASES .............................................................................................................9 CROSSWORD ..................................................................................................................3 COOKING HIGHLIGHTS ....................................................................................................12 SPORTS.........................................................................................................................4 SUDOKU .....................................................................................................................13 FEATURE STORY ...............................................................................................................5 WORD SEARCH / CABLE GUIDE .........................................................................................19 READY FOR A LIFT? Facelift | Neck Lift | Brow Lift | Eyelid Lift | Fractional Skin Resurfacing PicoSure® Skin Treatments | Volumizers | Botox® Surgical and non-surgical options to achieve natural and desired results! Leo D. Farrell, M.D. Deborah M. Farrell, M.D. www.Since1853.com MODEL Fredricksen Outpatient Center, 630 -

Spectacle, Masculinity, and Music in Blaxploitation Cinema

Spectacle, Masculinity, and Music in Blaxploitation Cinema Author Howell, Amanda Published 2005 Journal Title Screening the Past Copyright Statement © The Author(s) 2005. The attached file is posted here with permission of the copyright owner for your personal use only. No further distribution permitted. Please refer to the journal's website for access to the definitive, published version. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/4130 Link to published version http://www.latrobe.edu.au/screeningthepast/ Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Spectacle, masculinity, and music in blaxploitation cinema Spectacle, masculinity, and music in blaxploitation cinema Amanda Howell "Blaxploitation" was a brief cycle of action films made specifically for black audiences in both the mainstream and independent sectors of the U.S. film industry during the early 1970s. Offering overblown fantasies of black power and heroism filmed on the sites of race rebellions of the late 1960s, blaxploitation films were objects of fierce debate among social leaders and commentators for the image of blackness they projected, in both its aesthetic character and its social and political utility. After some time spent as the "bad object" of African-American cinema history,[1] critical and theoretical interest in blaxploitation resurfaced in the 1990s, in part due to the way that its images-- and sounds--recirculated in contemporary film and music cultures. Since the early 1990s, a new generation of African-American filmmakers has focused -

Sample Pages

EXPLANATORY NOTES Book Review Digest consists of the review listings and the Subject and Title Index. CONTENT OF THE DIGEST Review Listings The main body of the Digest lists the books reviewed in alphabetical order by the last name of the author or by title, when the title is the main entry. The book citation includes the title, authorship responsibility, edition, series, pagination, illustration note, binding, year of publication, and publisher. Subject headings are derived from Library of Congress Subject Headings. The International Standard Book Number and Library of Congress Control Number are given when available. A descriptive note, which is labeled SUMMARY, follows the book citation. It provides information about the content of the work and indicates the age or grade level for juvenile books. The source of the note is given in parentheses. The review citations are labeled REVIEW. They are arranged alphabetically by periodical title abbreviation, which is printed in italic type. The full name of the periodical and other information pertaining to it are given in the List of Periodicals. The review citation also includes the volume number, page, and date of the periodical and the name of the reviewer. When an excerpt of the review is provided, the excerpt follows the citation. Brackets and ellipsis points are used in the summaries and review excerpts to indicate interpolations and omissions from quoted texts. Added entries for co-authors, editors, illustrators, and variant titles send the user to the main entry. See references guide the reader from variant forms of an author’s name to the form that is used. -

Blaxploitation and the Cinematic Image of the South

Antoni Górny Appalling! Terrifying! Wonderful! Blaxploitation and the Cinematic Image of the South Abstract: The so-called blaxploitation genre – a brand of 1970s film-making designed to engage young Black urban viewers – has become synonymous with channeling the political energy of Black Power into larger-than-life Black characters beating “the [White] Man” in real-life urban settings. In spite of their urban focus, however, blaxploitation films repeatedly referenced an idea of the South whose origins lie in antebellum abolitionist propaganda. Developed across the history of American film, this idea became entangled in the post-war era with the Civil Rights struggle by way of the “race problem” film, which identified the South as “racist country,” the privileged site of “racial” injustice as social pathology.1 Recently revived in the widely acclaimed works of Quentin Tarantino (Django Unchained) and Steve McQueen (12 Years a Slave), the two modes of depicting the South put forth in blaxploitation and the “race problem” film continue to hold sway to this day. Yet, while the latter remains indelibly linked, even in this revised perspective, to the abolitionist vision of emancipation as the result of a struggle between idealized, plaintive Blacks and pathological, racist Whites, blaxploitation’s troping of the South as the fulfillment of grotesque White “racial” fantasies offers a more powerful and transformative means of addressing America’s “race problem.” Keywords: blaxploitation, American film, race and racism, slavery, abolitionism The year 2013 was a momentous one for “racial” imagery in Hollywood films. Around the turn of the year, Quentin Tarantino released Django Unchained, a sardonic action- film fantasy about an African slave winning back freedom – and his wife – from the hands of White slave-owners in the antebellum Deep South. -

Characters Reunite to Celebrate South Dakota's Statehood

2 x 2" ad 2 x 2" ad May 24 - 30, 2019 Buy 1 V A H A G R Z U N Q U R A O C Your Key 2 x 3" ad A M U S A R I C R I R T P N U To Buying Super Tostada M A R G U L I E S D P E T H N P B W P J M T R E P A Q E U N and Selling! @ Reg. Price 2 x 3.5" ad N A M M E E O C P O Y R R W I get any size drink FREE F N T D P V R W V C W S C O N One coupon per customer, per visit. Cannot be combined with any other offer. X Y I H E N E R A H A Z F Y G -00109093 Exp. 5/31/19 WA G P E R O N T R Y A D T U E H E R T R M L C D W M E W S R A Timothy Olyphant (left) and C N A O X U O U T B R E A K M U M P C A Y X G R C V D M R A Ian McShane star in the new N A M E E J C A I U N N R E P “Deadwood: The Movie,’’ N H R Z N A N C Y S K V I G U premiering Friday on HBO. -

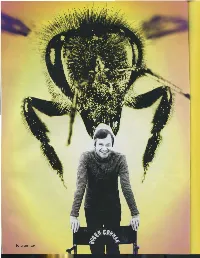

30 MENTAL FLOSS • HOW ROGER CORMAN REVOLUTIONIZED Cl EMA by IAN LENDLER

30 MENTAL_FLOSS • HOW ROGER CORMAN REVOLUTIONIZED Cl EMA BY IAN LENDLER MENTALFLOSS.COM 31 the Golden Age of Hollywood, big-budget movies were classy affairs, full of artful scripts and classically trained actors. And boy, were they dull. Then came Roger Corman, the King of the B-Movies. With Corman behind the camera, motorcycle gangs and mutant sea creatures .filled the silver screen. And just like that, movies became a lot more fun. .,_ Escape from Detroit For someone who devoted his entire life to creating lurid films, you'd expect Roger Corman's biography to be the stuff of tab loid legend. But in reality, he was a straight-laced workaholic. Having produced more than 300 films and directed more than 50, Corman's mantra was simple: Make it fast and make it cheap. And certainly, his dizzying pace and eye for the bottom line paid off. Today, Corman is hailed as one of the world's most prolific and successful filmmakers. But Roger Corman didn't always want to be a director. Growing up in Detroit in the 1920s, he aspired to become an engineer like his father. Then, at age 14, his ambitions took a turn when his family moved to Los Angeles. Corman began attending Beverly Hills High, where Hollywood gossip was a natural part of the lunchroom chatter. Although the film world piqued his interest Corman stuck to his plan. He dutifully went to Stanford and earned a degree in engineering, which he didn't particularly want. Then he dutifully entered the Navy for three years, which he didn't particularly enjoy. -

The Parallel Influences, Characteristics and Criticisms of the Blaxploitation Cinema and Gangsta Rap Movements Dustin Engels

Engels: Baadassss Gangstas: The Parallel Influences, Characteristics and JOURNAL OF HIP HOP STUDIES . Baadassss Gangstas: The Parallel Influences, Characteristics and Criticisms of the Blaxploitation Cinema and Gangsta Rap Movements Dustin Engels Abstract Serving as two of the most visible African American cultural movements, blaxploitation cinema and gangsta rap played essential roles in giving African American artists an outlet to establish a new black identity for mainstream audiences. After exploring the similarities between the cultural and economic conditions that spawned both movements, this essay examines the parallel techniques by which the preeminent entries in both genres established themselves as culturally relevant for African American audiences. These techniques included a reliance on place and space to establish authenticity, as well as employing African American myths and folklore such as the Signifying Monkey and the badman. By establishing themselves as mainstream representations of black identity, the harshest critics and staunchest defenders of both movements came from within the African American community, a clear indication of the important role each would play in establishing a new era of black representation in popular culture. In October 2012, New Orleans rapper Curren$y released a mixtape online for his fans entitled Priest Andretti. Taking its name from the main character of the 1972 blaxploitation film Super Fly, this fourteen-track mixtape frequently pays homage to the blaxploitation movement that occurred in the early 1970s by incorporating clips from Super Fly throughout, as well as including songs entitled “Max Julien” (star of the 1973 film The Mack) and “Cleopatra Jones” (title character of the 1973 film Cleopatra Jones).