The End of the Cold War: Berlin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The German Economy (Gec)

THE GERMAN ECONOMY (GEC) PROF. DR. CHRISTOPH KNOPPIK1 APRIL 20212 Course description An applied course on the German economy based on introductory economics. Basic economics as presented in introductory textbooks is briefly reviewed and serves as the basis for analysis. The focus of the course, however, is on policy relevant topics ranging from historic economic events over recent economic reforms to current debates on economic policy. Historic economic episodes and events in Germany like hyperinflation, banking crises, great depression, currency reforms, Wirtschaftswunder, stagflation, German reunification, European monetary integration, and European eastern enlargement continue to inform economists and policy makers and still shape people’s attitudes towards questions of economic policy. Recent (and some not so recent) reforms and policy changes include the introduction of the Euro, the reform of labour market institutions (Hartz I to IV), and many more. Current debates on economic policy and economic policy challenges range from the privatisation and regulation of former state monopolies to the current financial and economic crisis. 1 Prof. Dr. Christoph Knoppik, Institutut für Volkswirtschaftslehre, einschließlich Ökonometrie, Universität Regensburg. Email: [email protected] WWW: https://www.uni-regensburg.de/wirtschaftswissenschaften/vwl-knoppik/ . Tel.: +49 (0) 941 943 2700 2 Version: 13.1.16. Stand/Release: April 2021. GEC.DOCX at C:\LEHRE\GEC\GEC.DOCX . Prof. Dr. Christoph Knoppik The German Economy Target group The course is primarily targeted at foreign exchange students who want to get acquainted with their host country’s economy and economic policy debate. The course language is English. The course is part of the 2nd phase of the bachelor program in economics. -

David Hume Kennerly Archive Creation Project

DAVID HUME KENNERLY ARCHIVE CREATION PROJECT 50 YEARS BEHIND THE SCENES OF HISTORY The David Hume Kennerly Archive is an extraordinary collection of images, objects and recollections created and collected by a great American photographer, journalist, artist and historian documenting 50 years of United States and world history. The goal of the DAVID HUME KENNERLY ARCHIVE CREATION PROJECT is to protect, organize and share its rare and historic objects – and to transform its half-century of images into a cutting-edge digital educational tool that is fully searchable and available to the public for research and artistic appreciation. 2 DAVID HUME KENNERLY Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist David Hume Kennerly has spent his career documenting the people and events that have defined the world. The last photographer hired by Life Magazine, he has also worked for Time, People, Newsweek, Paris Match, Der Spiegel, Politico, ABC, NBC, CNN and served as Chief White House Photographer for President Gerald R. Ford. Kennerly’s images convey a deep understanding of the forces shaping history and are a peerless repository of exclusive primary source records that will help educate future generations. His collection comprises a sweeping record of a half-century of history and culture – as if Margaret Bourke-White had continued her work through the present day. 3 HISTORICAL SIGNIFICANCE The David Hume Kennerly collection of photography, historic artifacts, letters and objects might be one of the largest and most historically significant private collections ever produced and collected by a single individual. Its 50-year span of images and objects tells the complete story of the baby boom generation. -

Presidential Handwriting File, 1981-1989

PRESIDENTIAL HANDWRITING FILE: PRESIDENTIAL RECORDS: 1981-1989 – REAGAN LIBRARY COLLECTIONS This collection is available in whole for research use. Some folders may still have withdrawn material due to Freedom of Information Act restrictions. Most frequent withdrawn material is national security classified material, personal privacy, protection of the President, etc. PRESIDENTIAL HANDWRITING FILE: PRESIDENTIAL RECORDS: 1981-1989 The Presidential Handwriting File is an artificial collection created by the White House Office of Records Management (WHORM). The Presidential Handwriting File consists of a variety of documents that Ronald Reagan either annotated, edited, or wrote in his own hand. When documents containing the president's handwriting were received at WHORM for filing, the original was placed in the Presidential Handwriting File and arranged by the order received. A photocopy of the document was placed in the appropriate category of the WHORM: Subject File. The first page of the casefile was stamped Handwriting File, indicating the location of the original documents. However, WHORM often failed to indicate on the original documents the original location (i.e. the six digit tracking number, Subject Category Code). The Presidential Handwriting File, as created by the White House, did not contain handwriting found in staff and office files. The Library will be creating a further series of handwriting material from staff and office files. In order to provide better access to the Presidential Handwriting File, the collection has been arranged into six series. Each series is arranged chronologically by the date of the document. Each document has been marked with the appropriate WHORM: Subject File category and a six digit tracking number. -

BUSINESS Effbtrs At

rr-sr.- 20 - MANCHESTER HERALD. Sat.. Dec. 18. 1982 BUSINESS Take a door tour Did missing mom Were voters In Manchester live in town? just ignored? . page 6 Labor-management . page 11 .. .page 3 A. -4/7C Iowa construction industry, a new approach is cutting costs, saving time, benefiting all Manchester, Conn. dy James Kay UNICON had a few other projects prise one of the two problems that More light snow United Press International following completion of the civic most often lead to work stoppages. Monday, Dec. 20, 1982 center — including construction of Stroh .said. The other is contract dis tonight, Tuesday Single copy 25(t DES MOINES. Iowa (UPll - The an altar for Pope John Paul IPs visit putes. — See page 2 image is familiar: to Des Moines in October. 1979 — Unions, the memorandum lUrralb Representatives of management but the concept slowed to the point stipulates, must pledge "that no and labor glare at one another where most in the industry forgot picketing or strikes will be used to across a negotiating table Each about it settle jurisdictional disputes." side, distrusting of the other, makes Then competition from nonunion Labor also must pledge there will be pie-in-the-sky demands and companies bred new interest in no "illegal work stoppages and il counterdemands Perhaps, even- I' N I C O N . Stroh said the legal strikes." tuaiiy. strikes bring work to a grin organization's 10-member board of The memorandum also includes a ding halt directors. had to discern what at half-dozen joint contractor-union Such .scenarios have been played tractions nonunion work held for stipulations The UNICON idea has sparked in Congress inches out since iabor first organized more prospective buyers. -

In the Court of Chancery of the State of Delaware

IN THE COURT OF CHANCERY OF THE STATE OF DELAWARE THOMAS P. DiNAPOLI, COMPTROLLER OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK, AS ADMINISTRATIVE PUBLIC VERSION HEAD OF THE NEW YORK STATE FILED ON: June 30, 2020 AND LOCAL RETIREMENT SYSTEM, AND AS TRUSTEE FOR THE NEW YORK STATE COMMON RETIREMENT FUND, and FIRE AND POLICE PENSION ASSOCIATION OF COLORADO, Plaintiffs, v. C.A. No. 2020-0465-AGB KENNETH M. DUBERSTEIN, MIKE S. ZAFIROVSKI, ARTHUR D. COLLINS JR., EDWARD M. LIDDY, ADMIRAL EDMUND P. GIAMBASTIANI JR., DAVID L. CALHOUN, SUSAN C. SCHWAB, RONALD A. WILLIAMS, LAWRENCE W. KELLNER, LYNN J. GOOD, ROBERT A. BRADWAY, RANDALL L. STEPHENSON, CAROLINE B. KENNEDY, W. JAMES MCNERNEY JR., DENNIS A. MUILENBURG, KEVIN G. MCALLISTER, RAYMOND L. CONNER, GREG SMITH, J. MICHAEL LUTTIG, GREG HYSLOP, and DIANA L. SANDS, Defendants. and THE BOEING COMPANY, Nominal Defendant. VERIFIED STOCKHOLDER DERIVATIVE COMPLAINT {FG-W0467081.} Plaintiffs Thomas P. DiNapoli, Comptroller of the State of New York, as Administrative Head of the New York State and Local Retirement System, and as Trustee of the New York State Common Retirement Fund, and Fire and Police Pension Association of Colorado, stockholders of The Boeing Company (“Boeing,” the “Company,” or “Nominal Defendant”), bring this action on Boeing’s behalf against the current and former officers and directors identified below (collectively, “Defendants”) arising from their failure to monitor the safety of Boeing’s 737 MAX airplanes. The allegations in this Complaint are based on the knowledge of Plaintiffs as to themselves, and on information and belief, including the review of publicly available information and documents obtained under 8 Del. -

Straightened up and Flying Right

http://www.usatoday.com/money/companies/management/2007-02-25-exec-profile-boeing_x.htm Page 1 of 4 thing every day." Straightened up and After 20 months as CEO, McNerney is still getting noticed most for keeping the aerospace giant, No. flying right 26 on the Fortune 500, on the straight and narrow. All the while, McNerney has presided over soaring Updated 2/26/2007 9:08 AM ET sales and a 43% rise in Boeing's share price. Chicago-based Boeing is the world's top-selling builder of passenger jets, and second-biggest defense contractor behind Lockheed Martin. Boeing was in a steep dive when McNerney took control in July 2005. Former CEO Phil Condit, a visionary aerospace engineer known for living large, was forced out in the wake of defense procurement scandals that landed Druyun and Sears in prison. McNerney's short-time predecessor, Harry Stonecipher, also charged by Boeing directors with restoring Boeing's integrity, was forced out after sending explicitly sexual e-mails to a Boeing executive with whom he was having an extramarital affair. McNerney, 57, represents a stark contrast to his predecessors by several measures. He's the first Boeing CEO from outside the company since World War II. In person, he comes across as low-key and proper. By Kevin P. Casey for USA TODAY In stints at General Electric and 3M, McNerney established himself in the nation's top tier of Boeing CEO Jim McNerney got lessons in values at an executive talent, the place where the largest early age. Ethics "was in our upbringing," a brother says. -

Germany: a Global Miracle and a European Challenge

GLOBAL ECONOMY & DEVELOPMENT WORKING PAPER 62 | MAY 2013 Global Economy and Development at BROOKINGS GERMANY: A GLOBAL MIRACLE AND A EUROPEAN CHALLENGE Carlo Bastasin Global Economy and Development at BROOKINGS Carlo Bastasin is a visiting fellow in the Global Economy and Development and Foreign Policy pro- grams at Brookings. A preliminary and shorter version of this study was published in "Italia al Bivio - Riforme o Declino, la lezione dei paesi di successo" by Paolazzi, Sylos-Labini, ed. LUISS University Press. This paper was prepared within the framework of “A Growth Strategy for Europe” research project conducted by the Brookings Global Economy and Development program. Abstract: The excellent performance of the German economy over the past decade has drawn increasing interest across Europe for the kind of structural reforms that have relaunched the German model. Through those reforms, in fact, Germany has become one of the countries that benefit most from global economic integration. As such, Germany has become a reference model for the possibility of a thriving Europe in the global age. However, the same factors that have contributed to the German "global miracle" - the accumulation of savings and gains in competitiveness - are also a "European problem". In fact they contributed to originate the euro crisis and rep- resent elements of danger to the future survival of the euro area. Since the economic success of Germany has translated also into political influence, the other European countries are required to align their economic and social models to the German one. But can they do it? Are structural reforms all that are required? This study shows that the German success depended only in part on the vast array of structural reforms undertaken by German governments in the twenty-first century. -

Declaration on Civility and Inclusive Leadership

DeclarPages08_finalALTS:Layout 1 4/25/08 11:32 AM Page 1 CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF THE PRESIDENCY Declaration on Civility and Inclusive Leadership THIRD EDITION he coming years demand greatness from our nation’s leaders and our citizens, as we navigate the significant domestic and international challenges that threaten our nation’s security and long-term prosperity. The difficulty of this task is magnified by our country’s political divisions, for today we are too much a house divided. Yet, if we unite to turn challenges into opportunities and pursue common goals, we surely will write another great chapter in America’s history. Civility and inclusive leadership are proven means of bridging political divisions and forging national unity and commitment. National resolve and unity of purpose are essential for marshalling the best talent, regardless of party affiliation, and are the elements required to develop a strategic consensus on the way forward. Civility does not require citizens to give up cherished beliefs or “dilute” their convictions. Rather, it requires respect, listening, and trust when interacting with those who hold differing viewpoints. Indeed, civility and inclusive leadership have often been exercised in the American experience as a means of moving to higher, common ground and developing more creative approaches to realize shared aspirations. Accordingly, the National Committee to Unite a Divided America strongly urges America’s leaders to draw strength and wisdom from our nation’s greatest achievements arising from inclusiveness -

The Impact of Nazi Economic Policies on German Food Consumtion, 1933-38

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Spoerer, Mark; Streb, Jochen Working Paper Guns and butter - but no margarine: The impact of Nazi economic policies on German food consumtion, 1933-38 FZID Discussion Paper, No. 23-2010 Provided in Cooperation with: University of Hohenheim, Center for Research on Innovation and Services (FZID) Suggested Citation: Spoerer, Mark; Streb, Jochen (2010) : Guns and butter - but no margarine: The impact of Nazi economic policies on German food consumtion, 1933-38, FZID Discussion Paper, No. 23-2010, Universität Hohenheim, Forschungszentrum Innovation und Dienstleistung (FZID), Stuttgart, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bsz:100-opus-5310 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/44969 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. -

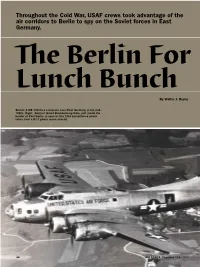

Throughout the Cold War, USAF Crews Took Advantage of the Air Corridors to Berlin to Spy on the Soviet Forces in East Germany

Throughout the Cold War, USAF crews took advantage of the air corridors to Berlin to spy on the Soviet forces in East Germany. The Berlin For Lunch Bunch By Walter J. Boyne Below: A RB-17G flies a mission over West Germany in the mid- 1950s. Right: Berlin’s famed Brandenburg Gate, just inside the border of East Berlin, is seen in this 1954 surveillance photo taken from a B-17 photo recon aircraft. 56 AIR FORCE Magazine / July 2012 hree air routes to West Berlin well as navigation and landing aids, were The corridors also led to the success- were established after the end of established. Air support to the conference ful covert reconnaissance that was about World War II to give the Western went well, and the Western Allies assumed to begin. Allies air access to their garrisons this would continue as they established The history of the reconnaissance squad- in the former Nazi capital. their garrisons. rons destined to become corridor intel- TWhen the Soviet Union imposed its ligence collectors is intricate. Although blockade in 1948, these air routes be- An Intricate History American recon activity may have begun came famous as the vital corridors of the However, shortly after the conference earlier, the earliest hard evidence notes the Berlin Airlift, which enabled the British ended, the Soviets began to complain that establishment of a special secret Douglas and Americans to supply the beleaguered the Allies were flying outside the agreed A-26 Invader flight within the 45th Re- city. It is less well known that they were corridors and this would not be tolerated. -

Ordinary Economic Voting Behavior in the Extraordinary Election of Adolf Hitler

THE JOURNAL OF ECONOMIC HISTORY VOLUME 68 DECEMBER 2008 NUMBER 4 Ordinary Economic Voting Behavior in the Extraordinary Election of Adolf Hitler GARY KING, ORI ROSEN, MARTIN TANNER, AND ALEXANDER F. WAGNER The enormous Nazi voting literature rarely builds on modern statistical or economic research. By adding these approaches, we find that the most widely accepted existing theories of this era cannot distinguish the Weimar elections from almost any others in any country. Via a retrospective voting account, we show that voters most hurt by the depression, and most likely to oppose the government, fall into separate groups with divergent interests. This explains why some turned to the Nazis and others turned away. The consequences of Hitler’s election were extraordinary, but the voting behavior that led to it was not. ow did free and fair democratic elections lead to the extraordinary H antidemocratic Nazi Party winning control of the Weimar Republic? The profound implications of this question have led “Who voted for Hitler?” to be the most studied question in the history of voting behavior research. Indeed, understanding who voted for Hitler is The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 68, No. 4 (December 2008). © The Economic History Association. All rights reserved. ISSN 0022-0507. Gary King is David Florence Professor of Government, Department of Government, Harvard University, Institute for Quantitative Social Science, 1737 Cambridge Street, Cambridge, MA 02138. E-mail: [email protected]. Ori Rosen is Associate Professor, Department of Mathematical Sciences, University of Texas at El Paso, Bell Hall 221, El Paso, TX 79968. E-mail: [email protected]. -

Designed by Professor Misty Sabol | 7 Days | June 2017

Designed by Professor Misty Sabol | 7 Days | June 2017 College Study Tour s BERLIN: THE CITY EXPERIENCE INCLUDED ON TOUR Round-trip flights on major carriers; Full-time Tour Director; Air-conditioned motorcoaches and internal transportation; Superior tourist-class hotels with private bathrooms; Breakfast daily; Select meals with a mix of local cuisine. Sightseeing: Berlin Alternative Berlin Guided Walking Tour Entrances: Business Visit KW Institute for Contemporary Art Berlinische Galerie (Museum of Modern Art) Topography of Terror Museum 3-Day Museum Pass BMW Motorcycle Plant Tour Reichstag Jewish Holocaust Memorial Overnight Stays: Berlin (5) NOT INCLUDED ON TOUR Optional excursions; Insurance coverage; Beverages and lunches (unless otherwise noted); Transportation to free-time activities; Customary gratuities (for your Tour Director, bus driver and local guide); Porterage; Adult supplement (if applicable); Weekend supplement; Shore excursion on cruises; Any applicable baggage-handing fee imposed by the airlines SIGN UP TODAY (see efcollegestudytours.com/baggage for details); Expenses caused by airline rescheduling, cancellations or delays caused by the airlines, bad efcst.com/1868186WR weather or events beyond EF’s control; Passports, visa and reciprocity fees YOUR ITINERARY Day 1: Board Your Overnight Flight to Berlin! Day 4: Berlin Day 2: Berlin Visit a Local Business Berlin's outstanding infrastructure and highly qualified and educated Arrive in Berlin workforce make it a competitive location for business. Today you will Arrive in historic Berlin, once again the German capital. For many visit a local business. (Please note this visit is pending confirmation years the city was defined by the wall that separated its residents. In and will be confirmed closer to departure.) the last decade, since the monumental events that ended Communist rule in the East, Berlin has once again emerged as a treasure of arts Receive a 3 Day Museum Pass and architecture with a vibrant heart.