Looking Through a New Lens: an Interview with Arlene Raven

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discovering the Contemporary

of formalist distance upon which modernists had relied for understanding the world. Critics increasingly pointed to a correspondence between the formal properties of 1960s art and the nature of the radically changing world that sur- rounded them. In fact formalism, the commitment to prior- itizing formal qualities of a work of art over its content, was being transformed in these years into a means of discovering content. Leo Steinberg described Rauschenberg’s work as “flat- bed painting,” one of the lasting critical metaphors invented 1 in response to the art of the immediate post-World War II Discovering the Contemporary period.5 The collisions across the surface of Rosenquist’s painting and the collection of materials on Rauschenberg’s surfaces were being viewed as models for a new form of realism, one that captured the relationships between people and things in the world outside the studio. The lesson that formal analysis could lead back into, rather than away from, content, often with very specific social significance, would be central to the creation and reception of late-twentieth- century art. 1.2 Roy Lichtenstein, Golf Ball, 1962. Oil on canvas, 32 32" (81.3 1.1 James Rosenquist, F-111, 1964–65. Oil on canvas with aluminum, 10 86' (3.04 26.21 m). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. 81.3 cm). Courtesy The Estate of Roy Lichtenstein. New Movements and New Metaphors Purchase Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alex L. Hillman and Lillie P. Bliss Bequest (both by exchange). Acc. n.: 473.1996.a-w. Artists all over the world shared U.S. -

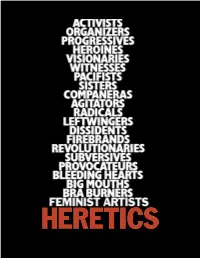

Heretics Proposal.Pdf

A New Feature Film Directed by Joan Braderman Produced by Crescent Diamond OVERVIEW ry in the first person because, in 1975, when we started meeting, I was one of 21 women who THE HERETICS is a feature-length experimental founded it. We did worldwide outreach through documentary film about the Women’s Art Move- the developing channels of the Women’s Move- ment of the 70’s in the USA, specifically, at the ment, commissioning new art and writing by center of the art world at that time, New York women from Chile to Australia. City. We began production in August of 2006 and expect to finish shooting by the end of June One of the three youngest women in the earliest 2007. The finish date is projected for June incarnation of the HERESIES collective, I remem- 2008. ber the tremendous admiration I had for these accomplished women who gathered every week The Women’s Movement is one of the largest in each others’ lofts and apartments. While the political movement in US history. Why then, founding collective oversaw the journal’s mis- are there still so few strong independent films sion and sustained it financially, a series of rela- about the many specific ways it worked? Why tively autonomous collectives of women created are there so few movies of what the world felt every aspect of each individual themed issue. As like to feminists when the Movement was going a result, hundreds of women were part of the strong? In order to represent both that history HERESIES project. We all learned how to do lay- and that charged emotional experience, we out, paste-ups and mechanicals, assembling the are making a film that will focus on one group magazines on the floors and walls of members’ in one segment of the larger living spaces. -

Patricia Hills Professor Emerita, American and African American Art Department of History of Art & Architecture, Boston University [email protected]

1 Patricia Hills Professor Emerita, American and African American Art Department of History of Art & Architecture, Boston University [email protected] Education Feb. 1973 PhD., Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. Thesis: "The Genre Painting of Eastman Johnson: The Sources and Development of His Style and Themes," (Published by Garland, 1977). Adviser: Professor Robert Goldwater. Jan. 1968 M.A., Hunter College, City University of New York. Thesis: "The Portraits of Thomas Eakins: The Elements of Interpretation." Adviser: Professor Leo Steinberg. June 1957 B.A., Stanford University. Major: Modern European Literature Professional Positions 9/1978 – 7/2014 Department of History of Art & Architecture, Boston University: Acting Chair, Spring 2009; Spring 2012. Chair, 1995-97; Professor 1988-2014; Associate Professor, 1978-88 [retired 2014] Other assignments: Adviser to Graduate Students, Boston University Art Gallery, 2010-2011; Director of Graduate Studies, 1993-94; Director, BU Art Gallery, 1980-89; Director, Museum Studies Program, 1980-91 Affiliated Faculty Member: American and New England Studies Program; African American Studies Program April-July 2013 Terra Foundation Visiting Professor, J. F. Kennedy Institute for North American Studies, Freie Universität, Berlin 9/74 - 7/87 Adjunct Curator, 18th- & 19th-C Art, Whitney Museum of Am. Art, NY 6/81 C. V. Whitney Lectureship, Summer Institute of Western American Studies, Buffalo Bill Historical Center, Cody, Wyoming 9/74 - 8/78 Asso. Prof., Fine Arts/Performing Arts, York College, City University of New York, Queens, and PhD Program in Art History, Graduate Center. 1-6/75 Adjunct Asso. Prof. Grad. School of Arts & Science, Columbia Univ. 1/72-9/74 Asso. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Barbara T. Smith the 21St Century Odyssey April 13

805 Traction Avenue Los Angeles CA 90013 213.625.1747 www.theboxla.com FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Barbara T. Smith The 21st Century Odyssey April 13 – May 25, 2019 Opening Reception: Saturday April 13, 6PM – 8PM Screenings: Saturday, April 20 & Saturday, May 18 Panel with the artist: Saturday, May 11 For The Box’s fifth solo exhibition of Barbara T. Smith’s work, the focus will be on The 21st Century Odyssey, a two year-long durational performance that took place from September 26, 1991 to September 26, 1993. These dates correlate with the opening and the closing of Biosphere 2, located near Tucson, Arizona, where her partner at the time, Dr. Roy Walford, was the interred physician. Smith took on the role of Homer’s Odysseus and traveled the world while Walford, confined inside the Biosphere 2 facility along with 7 other “Biospherians” for 2 years, was Penelope. For Smith, this work was an endeavor to attain a global consciousness while maintaining the connection between Biosphere 1 (the earth) and Biosphere 2. “I was holding Bio 2 in my heart and connecting, of course, with Roy as a vehicle of that connection.” As part of this work, Smith traveled extensively internationally and domestically and considered every aspect of her life in this two year period, from the exotic to the banal, as part of the performance. In Homer’s The Odyssey, Odysseus struggles for ten years to get home to Ithaca after his battles in the Trojan War. Between 1992 and 1993, Smith traveled to India, Nepal, Thailand, Australia, United Kingdom, Germany, and Norway; within the U.S., she went to Northern California, Hawaii and Seattle. -

Crossing Into Eighties Overview 2012

Crown Point Press Newsletter June 2012 The waterfall on Ponape, clockwise from front: Dorothy Wiley, Marina Abramovic, Joan Jonas, Daniel Buren, Chris Burden, and Mary Corse, 1980. Tom Marioni had named the conference “Word of Mouth” VISION #4. Twelve artists each gave a twelve-minute talk. Since LP records lasted twenty-four minutes, he had specified twelve-minute talks so we could put two on a side. Later we presented three records in a box. The records are white—“because it felt like we were landing from a flying saucer when we got off the plane in Ponape,” Tom remembers. The plane circled over what looked like a green dot in a blue sea, and we landed abruptly on a short white runway made of crushed coral with a great green rocky cliff at one end and the sea at the other. Against the cliff was a new low building. Shirtless workers in jeans hustled our bags from the plane into a big square hole in the building’s side, visibly pushing them onto a moving carousel. A man in a grass skirt and an inspector’s cap hustled us inside to claim them. The airport building was full of people, many in grass skirts, some (men and women) topless. CrOSSINg INTO THE EIgHTIES They clapped and whistled as we filed past. We learned later Escape Now and Again that word had circulated that we were an American rock group. In front of the airport was a flatbed truck with fourteen An excerpt from a memoir in progress by Kathan Brown white wicker chairs from the hotel dining room strapped On January 15, 1980, thirty-five artists and other art people, on the bed in two facing rows. -

Object/Poems: Alison Knowles's Feminist Archite(X)

JAMES FUENTES 55 Delancey Street New York, NY 10002 (212) 577-1201 [email protected] Nicole L. Woods Some visits later I arrived at his door with eleven color swatches…[Duchamp] chose one and set it aside on the buffet. After lunch, his wife Teeny picked up Object/Poems: the swatch and said, “Oh Marcel, when did you do this?” He smiled, took a pen- Alison Knowles’s cil and signed the swatch. The following year Marcel died. Arturo Schwarz wrote Feminist me suggesting I had the last readymade. Teeny and Richard Hamilton assured me Archite(x)ture that I did not, but that I had a piece of interesting memorabilia.4 You see you have to get right into it, as This brief experience with one of the most you do with any good book, and you must prolific and influential artists of the twen- become involved and experience it your- tieth century was but one of many chance self. Then you will know something and encounters that would characterize Knowles’s feel something. Let us say that it provides artistic practice for more than four decades. a milieu for your experience but what you The experience of seeing the readymade pro- bring to it is the biggest ingredient, far cess up close served to reaffirm her sense of more important than what is there. the exquisite possibilities of unintentional —Alison Knowles 1 choices, artistic and otherwise. Indeed, Knowles’s chance-derived practice throughout the 1960s and 1970s consistently sought to The world of objects is a kind of book, in frame a collection of sensorial data in vari- which each thing speaks metaphorically ous manifestations: from language-based of all others…and is read with the whole notational scores and performances to objet body, in and through the movements and trouvé experiments within her lived spaces, displacements which define the space of computer-generated poems, and large-scale objects as much as they are defined by it. -

“My Personal Is Not Political?” a Dialogue on Art, Feminism and Pedagogy

Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies Vol. 5, No. 2, July 2009 “My Personal Is Not Political?” A Dialogue on Art, Feminism and Pedagogy Irina Aristarkhova and Faith Wilding This is a dialogue between two scholars who discuss art, feminism, and pedagogy. While Irina Aristarkhova proposes “active distancing” and “strategic withdrawal of personal politics” as two performative strategies to deal with various stereotypes of women's art among students, Faith Wilding responds with an overview of art school’s curricular within a wider context of Feminist Art Movement and the radical questioning of art and pedagogy that the movement represents Using a concrete situation of teaching a women’s art class within an art school environment, this dialogue between Faith Wilding and Irina Aristakhova analyzes the challenges that such teaching represents within a wider cultural and historical context of women, art, and feminist performance pedagogy. Faith Wilding has been a prominent figure in the feminist art movement from the early 1970s, as a member of the California Arts Institute’s Feminist Art Program, Womanhouse, and in the recent decade, a member of the SubRosa, a cyberfeminist art collective. Irina Aristarkhova, is coming from a different history to this conversation: generationally, politically and theoretically, she faces her position as being an outsider to these mostly North American and, to a lesser extent, Western European developments. The authors see their on-going dialogue of different experiences and ideas within feminism(s) as an opportunity to share strategies and knowledges towards a common goal of sustaining heterogeneity in a pedagogical setting. First, this conversation focuses on the performance of feminist pedagogy in relation to women’s art. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Re: Paik. On time, changeability and identity in the conservation of Nam June Paik’s multimedia installations Hölling, H.B. Publication date 2013 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Hölling, H. B. (2013). Re: Paik. On time, changeability and identity in the conservation of Nam June Paik’s multimedia installations. Boxpress. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:26 Sep 2021 Appendix Nam June Paik’s Collaborators, Fabricators and Assistants1 Shuya Abe (born 1932) Japanese electrical engineer and co-inventor of the video-synthesiser. In 1963, he became Paik’s seminal collaborator. The Paik–Abe synthesiser used video feedback, magnetic scan modulation, non-linear mixing, and colourised images from an array of cameras in a TV studio. -

Oh Chris, My Hero !... L'expérimentation Du Corps Par Chris Burden

Oh Chris, my hero !... L’expérimentation du corps par Chris Burden Jérôme Maigret Chris Burden, You’ll Never See my Face Cécile Perchet in Kansas-City, 1971 « Les religions jadis demandaient le sacrifice du corps humain ; le savoir appelle aujourd’hui à faire des expériences sur nous-mêmes, au sacrifice du sujet de connaissance.»1 1 – Michel Foucault, « Nietzsche, la généalogie, l’histoire », in Hommage à Jean Hyppolyte, Paris, Presses Universitaires partir des années soixante et essentiellement pendant les de France, 1971, p. 170. années soixante-dix, la tendance artistique aux États-Unis À comme en Europe prend des orientations différentes du schéma classique atelier-galerie-musée, en réaction contre le sys- tème du marché de l’art, par une attitude anti-commerciale et anti- institutionnelle. Le body art, art d’expérimentation corporelle, comme l’art conceptuel ou le land art qui apparaissent au même moment, a une activité créatrice de lien social et ne se préoccupe plus de produire un objet abouti et vendable. Pour la première fois dans l’histoire de l’art, l’artiste se risque à la blessure et à la mort. Des prouesses techniques sans précédent (armement nucléaire, industrialisation, conquête de la Lune…) font s’interroger l’homme à la fois sur sa grandeur et sa petitesse et confrontent sa propre iden- tité à une conscience cosmique nouvelle. Ainsi apparaît ce que l’on pourrait définir être une crise liée au sens du corps. Le body art, sous forme de performances ou d’actions ouvertes au public, apporte un renouvellement de l’imagerie du corps. -

Gender and the Collaborative Artist Couple

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Art and Design Theses Ernest G. Welch School of Art and Design Summer 8-12-2014 Gender and the Collaborative Artist Couple Candice M. Greathouse Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/art_design_theses Recommended Citation Greathouse, Candice M., "Gender and the Collaborative Artist Couple." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2014. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/art_design_theses/168 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Ernest G. Welch School of Art and Design at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art and Design Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GENDER AND THE COLLABORATIVE ARTIST COUPLE by CANDICE GREATHOUSE Under the Direction of Dr. Susan Richmond ABSTRACT Through description and analysis of the balancing and intersection of gender in the col- laborative artist couples of Marina Abramović and Ulay, John Lennon and Yoko Ono, and Chris- to and Jeanne-Claude, I make evident the separation between their public lives and their pri- vate lives, an element that manifests itself in unique and contrasting ways for each couple. I study the link between gendered negotiations in these heterosexual artist couples and this divi- sion, and correlate this relationship to the evidence of problematic gender dynamics in the art- works and collaborations. INDEX WORDS: -

Cassandra Langer Interviewed by Katie Cercone Date: Dec

NYFAI - Interview: Cassandra Langer interviewed by Katie Cercone Date: Dec. 15th, 2008 K.C. This is December 15th, 2008, Katie Cercone interviewing Cassandra Langer. C.L. I think it was important for most of us during the early 70s when the movement started up to establish institutions that would be accommodating to the radical new ideas that we had. We rejected the idea of accepting the old roles; of getting married being wives, and mothers . I think it’s hard for young people to understand that was the life you were groomed for. If you aspired to anything else, you were deemed oddball out , rushed off to a psychoanalyst or worse yet, thrown into a mental institution for readjustment. Establishing the Feminist Art Institute was an extremely revolutionary thing to do at that time. NYFAI provided a safe space for creative women who were trying to break out of those stereotypes. There was the California site that my friend Arlene Raven and others including Mimi Schapiro and Judy Chicago set up within the heart of a traditionally patriarchal art department spawning Woman House and other alternative spaces. Mimi, Nancy and people in New York, set up their own versions to begin with but they evolved into the Feminist Art Institute. For people like myself who were outsider-insiders, because I was teaching in South Carolina in the heart of limitation land and bigotry it was an oasis. The freedom of being able to talk with like-minded people was empowering. Founding the Collage Art Association’s Women’s Caucus for Art helped a lot. -

California Institute of the Arts Feminist Art Materials Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt2199r38x No online items Guide prepared by Abigail Dixon for History Associates Incorporated California Institute of the Arts California Institute of the Arts Archive California Institute of the Arts 24700 McBean Parkway Valencia, California 91355-2397 Phone: (661) 253-7882 Fax: (661) 254-4561 Email: [email protected] URL: http://calarts.edu/library/collections/archive 2008 CalArts-003 1 Administrative Summary Creator: California Institute of the Arts Title: California Institute of the Arts Feminist Art Materials Collection Dates: 1971-2007 Date (bulk): (bulk 1972-1977) Quantity: 2.3 cubic feet Repository: California Institute of the Arts. Library. Valencia, California 91355-2397 Abstract: The California Institute of the Arts Feminist Art Materials Collection contains articles, brochures, correspondence, exhibition catalogs, invoices, newsletters, and other materials documenting the influence of feminism on the training of artists and the making of art. The collection covers the years 1971 to 2007 with the bulk of the material ranging from 1972 to 1977. California Institute of the Arts Archive Identification: CalArts-003 Language of Material: English Restrictions on Access This collection is open for research with permission from California Institute of the Arts Archive staff. Publication Rights Property rights and literary rights reside with California Institute of the Arts. For permission to reproduce or to publish, please contact California Institute of the Arts Archive staff. Related Material Located in the California Institute of the Arts Archive Archives Unprocessed collections with related material are located in the CalArts Library Archives. Preferred Citation California Institute of the Arts Feminist Art Materials Collection.