The Relationship Between Public Revelation and Private Revelations in the Theology of Saint John of the Cross Steven L. Payne

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

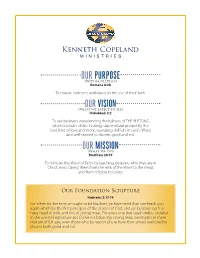

2018 KCM Purpose Vision Mission Statement.Indd

OUR PURPOSE (Why KCM Exists) Romans 8:28 To mature believers worldwide in the use of their faith. OUR VISION (What We Expect to See) Habakkuk 2:2 To see believers experiencing the fullness of THE BLESSING which includes divine healing, supernatural prosperity, the God kind of love and more; operating skillfully in God’s Word; and well-trained to discern good and evil. OUR MISSION (What We Do) Matthew 28:19 To minister the Word of Faith, by teaching believers who they are in Christ Jesus; taking them from the milk of the Word to the meat, and from religion to reality. Our Foundation Scripture Hebrews 5:12-14 For when for the time ye ought to be teachers, ye have need that one teach you again which be the first principles of the oracles of God; and are become such as have need of milk, and not of strong meat. For every one that useth milk is unskilful in the word of righteousness: for he is a babe. But strong meat belongeth to them that are of full age, even those who by reason of use have their senses exercised to discern both good and evil. STATEMENT OF FAITH • We believe in one God—Father, Son and Holy Spirit, Creator of all things. • We believe that the Lord Jesus Christ, the only begotten Son of God, was conceived of the Holy Spirit, born of the Virgin Mary, was crucified, died and was buried; He was resurrected, ascended into heaven and is now seated at the right hand of God the Father and is true God and true man. -

Speaking in Tongues

SPEAKING IN TONGUES “He who speaks in a tongue edifies himself” 1 Corinthians 14:4a Grace Christian Center 200 Olympic Place Pastor Kevin Hunter Port Ludlow, WA 8365 360 821 9680 mailing | 290 Olympus Boulevard Pastor Sherri Barden Port Ludlow, WA 98365 360 821 9684 Pastor Karl Barden www.GraceChristianCenter.us 360 821 9667 Our Special Thanks for the Contributions of Living Faith Fellowship Pastor Duane J. Fister Pastor Karl A. Barden Pastor Kevin O. Hunter For further information and study, one of the best resources for answering questions and dealing with controversies about the baptism of the Holy Spirit and the gift of speaking in tongues is You Shall Receive Power by Dr. Graham Truscott. This book is available for purchase in Shiloh Bookstore or for check-out in our library. © 1996 Living Faith Publications. All rights reserved. This material is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Unless otherwise identified, scripture quotations are from The New King James Version of the Bible, © 1982, Thomas Nelson Inc., Publishers. IS SPEAKING IN TONGUES A MODERN PHENOMENON? No, though in the early 1900s there indeed began a spiritual movement of speaking in tongues that is now global in proportion. Speaking in tongues is definitely a gift for today. However, until the twentieth century, speaking in tongues was a commonly occurring but relatively unpublicized inclusion of New Testament Christianity. Many great Christians including Justin Martyr, Iranaeus, Tertullian, Origen, Augustine, Chrysostom, Luther, Wesley, Finney, Moody, etc., either experienced the gift themselves or attested to it. Prior to 1800, speaking in tongues had been witnessed among the Huguenots, the Camisards, the Quakers, the Shakers, and early Methodists. -

A Peace Plan from Heaven

Relationship with GOD More than Just SUNDAY A Peace Plan from Heaven May 13 will mark the 100th Anniversary of the Mary reassured the children in a gentle voice, saying apparitions of Our Blessed Mother Mary to three “Do not be afraid; I will do you no harm.” She told shepherd children in the small village of Fatima in Lucia, “I come from Heaven.” She asked the children if Portugal. Taking place in 1917, Our Lady appeared they would “pray the Rosary every day, to bring peace six times to Lucia, 9, and her cousins Francisco, 8, to the world and an end to the war.” and his sister Jacinta, 6, on the 13th of each month On June 13, as Mary appeared to the three children, between May and October. Lucia asked, “What do you want me to do?” The Lady It is important to make a distinction between public responded, “Continue to pray the Rosary every day Revelation, the definitive teachings of Christ through and after the Glory Be of each mystery, add these the Catholic Church and “private” revelation, such as words: ‘O my Jesus, forgive us our sins! Save us from apparitions of Mary. According to the Catechism of the the fire of Hell. Lead all souls to Heaven, especially Catholic Church, “Throughout the ages, there have those in most need of Thy mercy.’” been so-called ‘private’ revelations, some of which Before the apparitions began, the children were have been recognized by the authority of the Church. devout in the Catholic Faith and spent time in prayer They do not belong, however, to the deposit of faith. -

282 Benjamin D. Sommer Revelation and Authority Is a Major Study

282 Book Reviews Benjamin D. Sommer Revelation and Authority: Sinai in Jewish Scripture and Tradition. The Anchor Yale Bible Reference Library. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT, 2015. 440 pp. $50.00 Revelation and Authority is a major study of the biblical texts describing the events at Sinai/Horeb and an important theological statement. Sommer claims that the book’s primary goal is to demonstrate that Rosenzweig’s and Heschel’s claims that the Torah is the beginning of the human response to God’s reve lation are not a radically new but continue a line of thought from the Torah itself. Along the way, Sommer shows that one can accept contemporary bibli cal scholarship and fully incorporate Torah into a modern theological system. Also, he establishes that a critical reading of the Torah places law at the center of revelation, and the compiling of the Torah itself illustrates that law changes and develops through time. In Sommer’s opinion, critical biblical scholarship should not present a problem for a contemporary Jewish theologian; rather, “… the Bible as recovered by biblical critics can serve as scripture for contem porary Judaism” (24). Sommer states that “moral issues rather than historicalphilological ones pose the most disturbing challenges” (28) to his accepting the Bible as Moses’ stenographic account of revelation. In place of Moses’ merely transcribing God’s words, Sommer argues for participatory revelation—the idea “that revela tion involved active contributions by both God and Israel” (1). If human activity, that is, Israel’s/Moses’ response to God’s revelation, produced the Bible, then its moral shortcomings can be explained. -

When We Speak in Tongues, We Are Making a Conscious Decision by Faith to Speak As the Holy Spirit Is Giving Us the Language Or the Words to Say

Purpose of Tongues Part 2 Review: - When we speak in tongues, we are making a conscious decision by faith to speak as the Holy Spirit is giving us the language or the words to say. - We can speak in two kinds of tongues: A tongue that is known in the earth and an unknown tongue that no man knows. - Tongues are used to convey a message to the church in the public setting and work in conjunction with the gift of interpretation. - The gift of tongues to convey a message to the church found 1 Corinthians 12 is not the same as the tongues you receive through the baptism in the Holy Ghost. o The gift of tongues mentioned in 1 Corinthians chapter 12 is a gift for ministering to the body of Christ in the public church service and must be accompanied with the gift of interpretation. o Not everyone will have this gift. o But the gift of tongues you receive through the baptism of the Holy Spirit is for everyone and for your personal edification. So, let’s talk about the tongue for personal edification. This tongue is the unknown tongue mentioned in 1 Corinthians 14:2 and 1 Corinthians 14:4. This is the tongue you receive when you are baptized in the Holy Spirit. Look what Paul says about this tongue in 1 Corinthians 14:4 - So, there’s a tongue that we can speak in that’s not a known tongue and it is for our personal edification o Once again this is a different tongue then the one referred to in 1 Corinthians 12. -

Lesson 2 Grade 10 11/22

Lesson 2 Grade 10 11/22 Bible Questions Luke 4-6 Chapter 4 1. How long was Jesus tempted by the devil in the wilderness? 2. What are the three temptations of Jesus? 3. Where does Jesus begin His preaching? 4. What town does Jesus encounter the man who is possessed by the evil spirit? 5. Who has the high fever that Jesus healed? 6. What does this mean about Peter? Chapter 5 7. Which 3 apostles were with Jesus when they caught an abundance of fish? 8. Where were they? 9. What does Jesus say to Peter after they catch all the fish? 10. What’s the name of the tax collector that follows Jesus? Chapter 6 11. What did Jesus do before He picked the 12 apostles the night before? 12. Name 6 of the 12 apostles 13. What did Jesus say we should do to those who curse and abuse us? 14. How is a good tree known from a bad tree? Catechism Questions Page: 6-10 1. What does God reveal fundamentally to man? 2. How did God reveal Himself in the beginning? 3. Who is the father of multitude of nations? 4. Which religions claim Abraham as their father? 5. What did God give to the Jews through Moses? 6. Who would come through the line of King David? 7. What stage is the fullness of God’s revelation? 8. What is the difference between public and private revelations? 9. Give three examples of private revelation. 10. What is Apostolic Tradition? 11. How are Scripture and Tradition different? How are they the same? 12. -

Blessing and Investiture Brown Scapular.Pdf

Procedure for Blessing and Investiture Latin Priest - Ostende nobis Domine misericordiam tuam. Respondent - Et salutare tuum da nobis. P - Domine exaudi orationem meum. R - Et clamor meus ad te veniat. P - Dominus vobiscum. R - Et cum spiritu tuo. P - Oremus. Domine Jesu Christe, humani generis Salvator, hunc habitum, quem propter tuum tuaeque Genitricis Virginis Mariae de Monte Carmelo, Amorem servus tuus devote est delaturus, dextera tua sancti+fica, tu eadem Genitrice tua intercedente, ab hoste maligno defensus in tua gratia usque ad mortem perseveret: Qui vivis et regnas in saecula saeculorum. Amen. THE PRIEST SPRINKLES WITH HOLY WATER THE SCAPULAR AND THE PERSON(S) BEING ENROLLED. HE THEN INVESTS HIM (THEM), SAYING: P - Accipite hunc, habitum benedictum precantes sanctissima Virginem, ut ejus meritis illum perferatis sine macula, et vos ab omni adversitate defendat, atque advitam perducat aeternam. Amen. AFTER INVESTITURE THE PRIEST CONTINUES WITH THE PRAYERS: P - Ego, ex potestate mihi concessa, recipio vos ad participationem, omnium bonorum spiritualium, qua, cooperante misericordia Jesu Christi, a Religiosa de Monte Carmelo peraguntur. In Nomine Patris + et Filii + et Spiritus Sancti. + Amen. Benedicat + vos Conditor caeli at terrae, Deus omnipotens, qui vos cooptare dignatus est in Confraternitatem Beatae Mariae Virginis de Monte Carmelo: quam exoramus, ut in hore obitus vestri conterat caput serpentis antiqui, atque palmam et coronam sempiternae hereditatis tandem consequamini. Per Christum Dominum nostrum. R - Amen. THE PRIEST THEN SPRINKLES AGAIN WITH HOLY WATER THE PERSON(S) ENROLLED. English Priest - Show us, O Lord, Thy mercy. Respondent - And grant us Thy salvation. P - Lord, hear my prayer. R - And let my cry come unto Thee. -

A BIBLICAL STUDY of TONGUES

A BIBLICAL STUDY of TONGUES by the late Dr. John G. Mitchell reformatted and edited by: Mr. Gary S. Dykes [several comments were added by Mr. Dykes, in brackets] 1 Is speaking in tongues the evidence of a Spirit-filled, Spirit controlled life, the outward manifestation of the baptism ‘of the Spirit of God? This is one of the important questions at issue in the Christian world today. There is much preaching and writing concerning it, much discussion and questioning and inquiry. We hear of groups meeting in our universities and colleges, and in churches of every denomination, seeking this experience. In some of our religious magazines we find accounts of the experiences of those who claim a special anointing from God, evidenced by speaking tongues. I am sure this points out the fact that among God’s people there are many hungry hearts with a great desire to know God and a real longing to see the power of God manifested. However, one thing I have noticed as I have heard and read these testimonies is that the emphasis has always been an the experience and there is very little said about the teaching of the Scripture concerning it. There is a seeking of an experience rather than a searching of the Word of God. I believe the reason why there is misunderstanding and confusion is because there is not a clear understanding of all that the Word declares. Whatever we seek let us be sure that it is according to the Word of God. This cannot be emphasized too much. -

Preparing for Lent Fr

February 24, 2019 1 St. Elizabeth Ann Seton Catholic Church Preparing for Lent Fr. Steve Gruno, CEO of www.WordOnFire.org 6646 Addicks Satsuma Road In two weeks, the Church begins the penitential practices of Lent. Houston, TX 77084 Penitential practices are virtuous works through which we demon- 281-463-7878 strate the sincerity of our profession of faith and discipline our desires so that we might better serve the mission of the Church. Lent is an extended period of time during which the Church prepares herself to celebrate the great mysteries of Holy Week. www.SeasCatholic.org www.SeasCatholic.org Continued on page 12... February 24, 2019 2 Mass Schedule Monday—Friday 6:30 a.m. English 9:00 a.m. English 7:00 p.m. English On Friday, the evening Mass Is in Vietnamese (Tiếng Việt) 7:30 p.m. Miércoles en Español The First Friday devotion arose from a private revelation to St. Margaret Saturday Mary Alocoque in the seventeenth century. 9:00 a.m. English The devotion involves participating in the Holy Mass and receiving Holy Anticipated Masses Communion on nine consecutive first Fridays of the month. It is like a 5:00 p.m. English novena which is prayed over consecutive months rather than over con- 6:30 p.m. Español secutive days, and is offered for the particular intention of reparation to 8:00 p.m. Tiếng Việt the Sacred Heart of Jesus. Sunday Masses Devotion to the Sacred Herat is call to the faithful to “stand in the gap” 7:00 a.m. -

The Catholic Faith Divine Revelation

The Catholic Faith Divine Revelation Knowing God Faith is a gift from God that allows us to believe in him and all that he has revealed. We can know God from creation. Saint Thomas Aquinas’ five proofs of knowing the existence of God by reason. First Mover: Anything moved is moved by another. There cannot be an infinite series of movers. So there must be a first mover. First Cause: Anything caused is caused by another. There cannot be an infinite series of causes. So there must be a first cause. Necessary Being: Not everything is contingent. So there is a necessary being upon which other beings depend for their existence. Greatest Being: Whatever is great to any degree gets its greatness from that which is the greatest. So there is a greatest being, which is the source of all greatness. Intelligent Designer: Whatever acts for an end must be directed by an intelligent being. So the world must have an intelligent designer. It is not contrary to the faith to accept the theory of evolution, so long as we understand that God is our Creator, man is the highest level of creation, and man’s soul is created only by God. Man – Made in God’s Image Man is composed of a body and a soul. Man’s soul is rational. The intellect is a power of the rational soul. Man is created in God’s image. All men are created equal in dignity. Man is called to relationship and stewardship. Revelation God has revealed himself out of love for man. -

Gifts of the Spirit 02 the Three Revelation Gifts Word of Wisdom a Word of Wisdom Has Unique Characteristics. Why Do We Need

Notes Gifts of the Spirit 02 with Dr. Bob Abramson The Three Revelation Gifts 1 Corinthians 12:7-8, 10 (NKJV) “But the manifestation of the God uses these Spirit is given to each one for the profit of all : {8} for to one is three revelation given the word of wisdom through the Spirit, to another the word gifts to reveal of knowledge through the same Spirit…, {10} to another the things working of miracles, to another prophecy, to another discerning supernaturally of spirits, to another different kinds of tongues, to another the that we could not interpretation of tongues.” know through our Word of Wisdom natural senses. A word of wisdom is a word, proclamation, or declaration, that is supernaturally given by God. Its purpose is to meet the need of a particular future occasion or problem. • It is given to a person through words, visions or dreams. It provides understanding and instruction on what action to take. • It is not revealed through human ability or natural wisdom. It is a God’s revelation of His plans and purposes. A Word of Wisdom has Unique Characteristics. • It is purely supernatural in origin. It is not natural wisdom. It does not follow natural rules of reason and thought. • It is supernatural in its function. It does not depend on human ability. It depends upon God. • It is supernatural in its revelation. It comes to us by the Holy Spirit. It is divine counsel that He gives to us. Why do we need a Word of Wisdom? The Holy Spirit provides a word of wisdom at the appropriate time, so we can apply supernaturally-given wisdom to a particular problem or need. -

Sermon for the Feast of St. Michael and All Angels – Revelation 12:7-12 “And the Great Dragon Was Thrown Down, That Ancient

Sermon for the Feast of St. Michael and All Angels – Revelation 12:7-12 “And the great dragon was thrown down, that ancient serpent, who is called the devil and Satan, the deceiver of the whole world—he was thrown down to the earth, and his angels were thrown down with him.” Grace, mercy, peace be to you from our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ. In today’s epistle, St. John, in the book of Revelation, tells of war. War is hell. It’s not pretty. It’s not easy. It’s messy and brutal. Ask any soldier who has come back from Iraq or Afghanistan – or who stormed the beaches of Normandy in WWII. Many will not speak of it. St. John was first addressing the early Christians who were being heavily persecuted by the Roman emperors. In Revelation’s war, Satan is cast down by the Archangel Michael and the other angels. They defeat the devil and he is stripped of his power. Strong angels battle against a strong foe. They are armed with sword and physical strength to defeat the prince of this world. But just what are the angels – and what do they do? The word “angel” means “messenger.” They serve before God's throne. They do His bidding. They worship God – as we confess in liturgy when we sing the song of the angels – the “Holy Holy Holy” – sung with angels and archangels and all the company of Heaven, including Michael, the cherubim, and the seraphim. They sing for joy and glory for salvation has come to us.