Anne Hutchinson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anne Hutchingson Assignment.Cwk

Anne Hutchinson Women were an important part of the workforce in the English colonies. However, they rarely helped bring about political change. One exception was a woman named Anne Hutchinson. Anne Hutchinson and her husband, William, settled in Boston in 1634. She worked as a midwife helping to deliver babies. Hutchinson was both intelligent and religious. John Winthrop, the governor of Massachusetts called her “a woman of ready wit and bold spirit”. It would be her bold spirit, however, which would bring her trouble with the Puritan officials. Hutchinson was well known At her trial, Hutchinson stood around Boston because she held Bible behind he beliefs. She answered all of readings on Sundays in her home. After the questions that were put to her by church, she and her friends would Governor Winthrop and other gather to discuss the minister’s sermon. government officials and she repeatedly Sometimes as many as 50 or 60 people exposed weaknesses in their arguments. would pack into her small house in order The court was not able to prove that she to listen to the discussions. had broken any laws or challenged any At first, Hutchinson only repeated church beliefs. Then after two days of what the minister had said. As time went questioning, Hutchinson made a serious on, however, she began to express her mistake. She told the court that God own ideas and interpretations. spoke directly to her. Sometimes she would even criticize the Members of the court were minister’s teachings. shocked. The Puritans believed that Hutchinson’s actions angered the God spoke only through the Bible and Puritan leaders. -

Circle of Scholars

Circle of Scholars 2021 Spring Online Circle Courses of Scholars Salve Regina University’s Circle of Scholars is a lifelong learning program for adults of all inclinations Online Seminar Catalog and avocations. We enlighten, challenge, and entertain. The student-instructor relationship is one of mutual respect and offers vibrant discussion on even the most controversial of global and national issues. We learn from each other with thoughtful, receptive minds. 360 degrees. Welcome to Salve Regina and enjoy the 2020 selection of fall seminars. Online registration begins on Wednesday, February 3, 2021 at noon www.salve.edu/circleofscholars Seminars are filled on a first-come, first-served basis. Please register online using your six-digit Circle of Scholars identification number (COSID). As in the past, you will receive confirmation of your credit card payment when you complete the registration process. For each seminar you register for, you will receive a Zoom email invitation to join the seminar 1-3 days before the start date. If you need assistance or have questions, please contact our office at (401) 341-2120 or email [email protected]. Important Program Adjustments for Spring 2021 • Most online seminars will offer 1.5 hour sessions. • Online class fees begin at $15 for one session and range to $85 for 8 sessions. • The 2019-2020 annual membership was extended from July 2019 - December 2020 due to COVID- 19. Membership renewal is for • Zoom is our online platform. If you do not have a Zoom account already, please visit the Zoom website to establish a free account at https://zoom.us. -

Carol Inskeep's Book List on Woman's Suffrage

Women’s Lives & the Struggle for Equality: Resources from Local Libraries Carol Inskeep / Urbana Free Library / [email protected] Cartoon from the Champaign News Gazette on September 29, 1920 (above); Members of the Chicago Teachers’ Federation participate in a Suffrage Parade (right); Five thousand women march down Michigan Avenue in the rain to the Republican Party Convention hall in 1916 to demand a Woman Suffrage plank in the party platform (below). General History of Women’s Suffrage Failure is Impossible: The History of American Women’s Rights by Martha E. Kendall. 2001. EMJ From Booklist - This volume in the People's History series reviews the history of the women's rights movement in America, beginning with a discussion of women's legal status among the Puritans of Boston, then highlighting developments to the present. Kendall describes women's efforts to secure the right to own property, hold jobs, and gain equal protection under the law, and takes a look at the suffrage movement and legal actions that have helped women gain control of their reproductive rights. She also compares the lifestyles of female Native Americans and slaves with those of other American women at the time. Numerous sepia photographs and illustrations show significant events and give face to important contributors to the movement. The appended list of remarkable women, a time line, and bibliographies will further assist report writers. Seneca Falls and the Origins of the Women’s Rights Movement by Sally G. McMillen. 2008. S A very readable and engaging account that combines excellent scholarship with accessible and engaging writing. -

104 the Trial of Anne Hutchinson, 1637

104 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Winter 2013 The Trial of Anne Hutchinson, 1637 105 Sex and Sin: The Historiography of Women, Gender, and Sexuality in Colonial Massachusetts SANDRA SLATER Abstract: Historians have long examined the powerful events that shaped the Massachusetts Bay in the colonial period, in part because the vast array of source material available for study, but more importantly, due to the enigmatic personalities who wrote those materials. Scholars of economics, politics, and theology all present differing explanations and descriptions of colonial Massachusetts, but it has only been in the last forty years that scholars have begun to think of the colonists as individuals. The advent of various civil rights movements of the 1960s and 1970s as well as the social turn in history, an increased focus on the histories of ordinary people and their experiences, questioned traditionally masculine and white-privileged histories by asking about everyone else. Women’s and gender studies and the even more recent studies of sexualities and queer history offer a valuable window through which to view and understand daily life. This article surveys gender histories of colonial Massachusetts, revolutionary works that uncover and discuss the lives of colonial people as gendered beings. Sandra Slater, an assistant professor of history at the College of Charleston, co-edited the collection Gender and Sexuality in Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Vol. 41 (1), Winter 2013 © Institute for Massachusetts Studies, Westfield State University 106 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Winter 2013 Indigenous North America, 1400-1850 (University of South Carolina Press, 2011).† * * * * * For decades, historians of colonial America focused their attention on the writings of John Cotton, Increase Mather, Cotton Mather, John Winthrop, and other leading male colonial figures, constructing a narrative of colonial Massachusetts that ignored the influences and contributions of women and racial minorities. -

Christianity of Conscience: Religion Over Politics in the Williams-Cotton Debate," Bound Away: the Liberty Journal of History: Vol

Bound Away: The Liberty Journal of History Volume 2 Issue 1 Article 4 June 2018 Christianity of Conscience: Religion Over Politics in the Williams- Cotton Debate Sophie Farthing [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/ljh Part of the History of Religion Commons, Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Farthing, Sophie (2018) "Christianity of Conscience: Religion Over Politics in the Williams-Cotton Debate," Bound Away: The Liberty Journal of History: Vol. 2 : Iss. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/ljh/vol2/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bound Away: The Liberty Journal of History by an authorized editor of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Christianity of Conscience: Religion Over Politics in the Williams-Cotton Debate Abstract This research project examines Roger Williams’s representation of the relationship between church and state as demonstrated in his controversy with the Massachusetts Bay Puritans, specifically in his pamphlet war with Boston minister John Cotton. Maintaining an emphasis on primary research, the essay explores Williams’s and Cotton’s writings on church-state relations and seeks to provide contextual analysis in light of religious, social, economic, and political influences. In addition, this essay briefly discusses well-known historiographical interpretations of Williams’ position and of his significance ot American religious and political thought, seeking to establish a synthesis of the evidence surrounding the debate and a clearer understanding of relevant historiography in order to demonstrate the unarguably Christian motivations for Williams’s advocacy of Separatism. -

Transcript of the Trial of Anne Hutchinson (1637)

Transcript of the Trial of Anne Hutchinson (1637) Puritans founded the Massachusetts Bay Colony in hopes of creating a model of Christian unity and order. However, in the 1630s, the Puritans confronted fundamental disagreements over theology. Anne Hutchinson arrived in Boston in 1634 and was a follower of John Cotton, who preached that salvation was achieved by faith alone, not by good works. Such ideas threatened the authority of Massachusetts’ ministers and magistrates. When Hutchinson began to hold meetings to discuss her theological views with other women and with men, Puritan magistrates charged her with heresy. This document is the transcript of her 1637 trial. Gov. John Winthrop: Mrs. Hutchinson, you are called here as one of those that have troubled the peace of the commonwealth and the churches here; you are known to be a woman that hath had a great share in the promoting and divulging of those opinions that are the cause of this trouble, and to be nearly joined not only in affinity and affection with some of those the court had taken notice of and passed censure upon, but you have spoken divers things, as we have been informed, very prejudicial to the honour of the churches and ministers thereof, and you have maintained a meeting and an assembly in your house that hath been condemned by the general assembly as a thing not tolerable nor comely in the sight of God nor fitting for your sex, and notwithstanding that was cried down you have continued the same. Therefore we have thought good to send for you to understand how things are, that if you be in an erroneous way we may reduce you that so you may become a profitable member here among us. -

Jennifer Rea

Jennifer Rea 3 Mar 2008 The Intimately Oppressed Throughout his book, A People’s History of the United States, Howard Zinn highlights several groups of people within the United States that experienced some form of subjugation. It is not surprising then, that Zinn devotes an entire chapter to reveal the unique challenges that women experienced. Out of the several women Zinn discusses, there are five that symbolize specific arenas of oppression in the United States. The influence of Abigail Adams’s political contribution is forever engrained in the minds of most women who pursue a political career. Even though she did not hold an official political position, she did have a significant influence on her husband, John Adams who eventually became president. Her letter to her husband during the rumblings of establishing independence expresses her devotion to the rights of women when she wrote, “I desire you would remember the ladies, and be more generous to them than your ancestors” (Zinn 110). Emma Willard not only made her beliefs known regarding the literacy of women, which contradicted the opinion of many men who felt women should avoid reading excessively, but she also founded the first recognized educational institution for women in 1812. She paved the way for women to explore educational opportunities and assert themselves as, “primary existences…not the satellites of men” (Zinn118). Religious oppression of women was often a characteristic of the Christian faith. Anne Hutchinson was one of the few women challenged the clergy. She held meetings where women spoke freely about their beliefs and how ordinary people like themselves could interpret the bible for themselves. -

The Antinomian Controversy and the Puritan Vision: a Historical Perspective on Christian Leadership by Jeffrey M

Ashland Theological Journal 35 (2003) The Antinomian Controversy and the Puritan Vision: A Historical Perspective on Christian Leadership by Jeffrey M. Kahl* Introduction The American Puritans are perhaps the most interesting, the most complex, and even the most misunderstood players in the fascinating saga called American History. Radical skeptics such as Perry Miller and William McLoughlin, as well as committed Christians such as H. Richard Niebuhr and J. I. Packer, have credited the Puritans with establishing the foundations of America's intellectual and cultural life. Undoubtedly this is the reason why the Puritans have merited the scholarly attention (on a much grander scale than other American colonial groups) not only of theologians and historians, but sociologists, psychologists, economists, literary critics, rhetoricians, artists, and others. It has been nearly four hundred years since they set foot on American soil, and information surrounding these colonists continues to attract the curiosity of scholars and laypersons alike. The Antinomian controversy of 1637 has elicited special attention as a crucial event in early American history, and researchers bringing different presuppositions and perspectives to the task have yielded different interpretations of the actual events surrounding the controversy. Writers such as Anne F. Withington, Jack Schwartz, and Richard B. Morris have concluded that the proceedings against Anne Hutchinson could rightly be characterized as a "show trial" and that the Puritan elders were more interested -

John Cotton's Middle Way

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 John Cotton's Middle Way Gary Albert Rowland Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Rowland, Gary Albert, "John Cotton's Middle Way" (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 251. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/251 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JOHN COTTON'S MIDDLE WAY A THESIS presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History The University of Mississippi by GARY A. ROWLAND August 2011 Copyright Gary A. Rowland 2011 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Historians are divided concerning the ecclesiological thought of seventeenth-century minister John Cotton. Some argue that he supported a church structure based on suppression of lay rights in favor of the clergy, strengthening of synods above the authority of congregations, and increasingly narrow church membership requirements. By contrast, others arrive at virtually opposite conclusions. This thesis evaluates Cotton's correspondence and pamphlets through the lense of moderation to trace the evolution of Cotton's thought on these ecclesiological issues during his ministry in England and Massachusetts. Moderation is discussed in terms of compromise and the abatement of severity in the context of ecclesiastical toleration, the balance between lay and clerical power, and the extent of congregational and synodal authority. -

Pebblego Biographies Article List

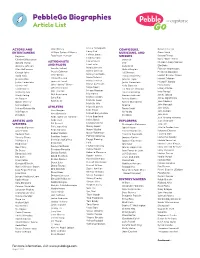

PebbleGo Biographies Article List Kristie Yamaguchi ACTORS AND Walt Disney COMPOSERS, Delores Huerta Larry Bird ENTERTAINERS William Carlos Williams MUSICIANS, AND Diane Nash LeBron James Beyoncé Zora Neale Hurston SINGERS Donald Trump Lindsey Vonn Chadwick Boseman Beyoncé Doris “Dorie” Miller Lionel Messi Donald Trump ASTRONAUTS BTS Elizabeth Cady Stanton Lisa Leslie Dwayne Johnson AND PILOTS Celia Cruz Ella Baker Magic Johnson Ellen DeGeneres Amelia Earhart Duke Ellington Florence Nightingale Mamie Johnson George Takei Bessie Coleman Ed Sheeran Frederick Douglass Manny Machado Hoda Kotb Ellen Ochoa Francis Scott Key Harriet Beecher Stowe Maria Tallchief Jessica Alba Ellison Onizuka Jennifer Lopez Harriet Tubman Mario Lemieux Justin Timberlake James A. Lovell Justin Timberlake Hector P. Garcia Mary Lou Retton Kristen Bell John “Danny” Olivas Kelly Clarkson Helen Keller Maya Moore Lynda Carter John Herrington Lin-Manuel Miranda Hillary Clinton Megan Rapinoe Michael J. Fox Mae Jemison Louis Armstrong Irma Rangel Mia Hamm Mindy Kaling Neil Armstrong Marian Anderson James Jabara Michael Jordan Mr. Rogers Sally Ride Selena Gomez James Oglethorpe Michelle Kwan Oprah Winfrey Scott Kelly Selena Quintanilla Jane Addams Michelle Wie Selena Gomez Shakira John Hancock Miguel Cabrera Selena Quintanilla ATHLETES Taylor Swift John Lewis Alex Morgan Mike Trout Will Rogers Yo-Yo Ma John McCain Alex Ovechkin Mikhail Baryshnikov Zendaya Zendaya John Muir Babe Didrikson Zaharias Misty Copeland Jose Antonio Navarro ARTISTS AND Babe Ruth Mo’ne Davis EXPLORERS Juan de Onate Muhammad Ali WRITERS Bill Russell Christopher Columbus Julia Hill Nancy Lopez Amanda Gorman Billie Jean King Daniel Boone Juliette Gordon Low Naomi Osaka Anne Frank Brian Boitano Ernest Shackleton Kalpana Chawla Oscar Robertson Barbara Park Bubba Wallace Franciso Coronado Lucretia Mott Patrick Mahomes Beverly Cleary Candace Parker Jacques Cartier Mahatma Gandhi Peggy Fleming Bill Martin Jr. -

(Microsoft Powerpoint

Milestones and Key Figures in Women’s History Life in Colonial America 1607-1789 Anne Hutchinson Challenged Puritan religious authorities in Massachusetts Bay Banned by Puritan authorities for: Challenging religious doctrine Challenging gender roles Challenging clerical authority Claiming to have had revelations from God Legal Status of Colonial Women Women usually lost control of their property when they married Married women had no separate legal identity apart from their husband Could NOT: Hold political office Serve as clergy Vote Serve as jurors Legal Status of Colonial Women Single women and widows did have the legal right to own property Women serving as indentured servants had to remain unmarried until the period of their indenture was over The Chesapeake Colonies Scarcity of women, especially in the 17 th century High mortality rate among men Led to a higher status for women in the Chesapeake colonies than those of the New England colonies The Early Republic 1789-1815 Abigail Adams An early proponent of women’s rights A famous letter to John demonstrates that some colonial women hoped to benefit from republican ideals of equality and individual rights “. And by the way in the new code of laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make, I desire you would remember the ladies, and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors. Remember, men would be tyrants if they could.” --Abigail Adams The Cult of Domesticity / Republican Motherhood The term cult of domesticity refers to the idealization of women in their roles as wives and mothers The term republican mother suggested that women would be responsible for rearing their children to be virtuous citizens of the new American republic By emphasizing family and religious values, women could have a positive moral influence on the American political character The Cult of Domesticity / Republican Motherhood Middle-Class Americans viewed the home as a refuge from the world rather than a productive economic unit. -

Historical Context and the Role of Women in Nathaniel Hawthorne’S the Scarlet Letter

Trabajo Fin de Grado Historical Context and the Role of Women in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter Autora Anastasia Tymkul Director Dr. Francisco Collado Rodríguez Facultad de Filosofía y Letras Grado en Estudios Ingleses 2015-2016 Repositorio de la Universidad de Zaragoza – Zaguan http://zaguan.unizar.es Contents Introduction..............................................................................................4 Hawthorne’s life and the writing of The Scarlet Letter............................6 19th-century Feminism and its influence on The Scarlet Letter................9 17th-century New England and Puritanism..............................................12 Hester Prynne as representation of old and new female images.............14 Pearl as symbol…....................................................................................17 Other female characters of the story........................................................19 Conclusion...............................................................................................20 Bibliography............................................................................................22 1 ABSTRACT The Scarlet Letter, written by Nathaniel Hawthorne, is considered one of the great masterpieces of American literature due to its originality. At first sight, it apparently deals with some historical events, but its quality as a “romance” involves many other themes such as a love story, social isolation and, the most relevant one for this work, prejudice and problems that women