Exploring Drug Gangs' Ever Evolving Tactics to Penetrate the Border And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Organized Crime and Terrorist Activity in Mexico, 1999-2002

ORGANIZED CRIME AND TERRORIST ACTIVITY IN MEXICO, 1999-2002 A Report Prepared by the Federal Research Division, Library of Congress under an Interagency Agreement with the United States Government February 2003 Researcher: Ramón J. Miró Project Manager: Glenn E. Curtis Federal Research Division Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 20540−4840 Tel: 202−707−3900 Fax: 202−707−3920 E-Mail: [email protected] Homepage: http://loc.gov/rr/frd/ Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Criminal and Terrorist Activity in Mexico PREFACE This study is based on open source research into the scope of organized crime and terrorist activity in the Republic of Mexico during the period 1999 to 2002, and the extent of cooperation and possible overlap between criminal and terrorist activity in that country. The analyst examined those organized crime syndicates that direct their criminal activities at the United States, namely Mexican narcotics trafficking and human smuggling networks, as well as a range of smaller organizations that specialize in trans-border crime. The presence in Mexico of transnational criminal organizations, such as Russian and Asian organized crime, was also examined. In order to assess the extent of terrorist activity in Mexico, several of the country’s domestic guerrilla groups, as well as foreign terrorist organizations believed to have a presence in Mexico, are described. The report extensively cites from Spanish-language print media sources that contain coverage of criminal and terrorist organizations and their activities in Mexico. -

05-05-10 FBI Perkins and DEA Placido Testimony Re Drug Trafficking Violence in Mexico

STATEMENT FOR THE RECORD OF ANTHONY P. PLACIDO ASSISTANT ADMINISTRATOR FOR INTELLIGENCE DRUG ENFORCEMENT ADMINISTRATION AND KEVIN L. PERKINS ASSISTANT DIRECTOR CRIMINAL INVESTIGATIVE DIVISION FEDERAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION BEFORE THE SENATE CAUCUS ON INTERNATIONAL NARCOTICS CONTROL UNITED STATES SENATE ENTITLED “DRUG TRAFFICKING VIOLENCE IN MEXICO: IMPLICATIONS FOR THE UNITED STATES” PRESENTED MAY 5, 2010 Statement of Anthony P. Placido Assistant Administrator for Intelligence Drug Enforcement Administration and Kevin L. Perkins Assistant Director, Criminal Investigative Division Federal Bureau of Investigation “Drug Trafficking Violence in Mexico: Implications for the United States” U.S. Senate Caucus on International Narcotics Control INTRODUCTION Chairman Feinstein, Co-Chairman Grassley, and distinguished Members of the Caucus, on behalf of Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) Acting Administrator Michele Leonhart and Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) Director Robert S. Mueller, III, we appreciate your invitation to testify today regarding violence in Mexico and its implications for the United States. The Department of Justice law enforcement agencies have outstanding relationships with law enforcement agencies on both sides of the border. With the assistance of our counterparts, the Department strives to coordinate investigative activity and develop intelligence in order to efficiently and effectively manage law enforcement efforts with the goal of identifying, infiltrating, and dismantling drug trafficking organizations that are directly responsible for the violence in Mexico. The DEA, in conjunction with the FBI, has been at the forefront of U.S. efforts to work with foreign law enforcement counterparts in confronting the organizations that profit from the global drug trade. The Department recognizes that in order to effectively attack the international drug trade it has to forward deploy its personnel into the foreign arena. -

Propaganda in Mexico's Drug War (2012)

PROPAGANDA IN MEXICO’S DRUG WAR America Y. Guevara Master of Science in Intelligence and National Security Studies INSS 5390 December 10, 2012 1 Propaganda has an extensive history of invisibly infiltrating society through influence and manipulation in order to satisfy the originator’s intent. It has the potential long-term power to alter values, beliefs, behavior, and group norms by presenting a biased ideology and reinforcing this idea through repetition: over time discrediting all other incongruent ideologies. The originator uses this form of biased communication to influence the target audience through emotion. Propaganda is neutrally defined as a systematic form of purposeful persuasion that attempts to influence the emotions, attitudes, opinions, and actions of specified target audiences for ideological, political or commercial purposes through the controlled transmission of one-sided messages (which may or may not be factual) via mass and direct media channels.1 The most used mediums of propaganda are leaflets, television, and posters. Historical uses of propaganda have influenced political or religious schemas. The trend has recently shifted to include the use of propaganda for the benefit of criminal agendas. Mexico is the prime example of this phenomenon. Criminal drug trafficking entities have felt the need to incite societal change to suit their self-interest by using the tool of propaganda. In this study, drug cartel propaganda is defined as any deliberate Mexican drug cartel act meant to influence or manipulate the general public, rivaling drug cartels and Mexican government. Background Since December 11, 2006, Mexico has suffered an internal war, between quarreling cartels disputing territorial strongholds claiming the lives of approximately between 50,000 and 100,000 people, death estimates depending on source.2 The massive display of violence has strongly been attributed to President Felipe Calderon’s aggressive drug cartel dismantling policies and operatives. -

Mexico Extradites 13 Individuals Accused of Drug Trafficking, Other Crimes to the U.S

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository SourceMex Latin America Digital Beat (LADB) 10-14-2015 Mexico Extradites 13 Individuals Accused of Drug Trafficking, Other Crimes to the U.S. Carlos Navarro Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sourcemex Recommended Citation Navarro, Carlos. "Mexico Extradites 13 Individuals Accused of Drug Trafficking, Other Crimes to the U.S.." (2015). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sourcemex/6206 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Latin America Digital Beat (LADB) at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in SourceMex by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LADB Article Id: 79792 ISSN: 1054-8890 Mexico Extradites 13 Individuals Accused of Drug Trafficking, Other Crimes to the U.S. by Carlos Navarro Category/Department: Mexico Published: 2015-10-14 In early October, the Mexican government announced the extradition of 13 individuals wanted in the US on charges of drug trafficking and other crimes, including Édgar Valdez Villarreal of the Beltrán Leyva drug-trafficking organization and Jorge Costilla Sánchez of the Gulf cartel. Valdez Villarreal, most commonly known by his nickname La Barbie, is a US citizen who rose through the ranks of the Beltrán Leyva cartel, which operated primarily in central Mexico. The accused were all being held in El Altiplano, the same maximum-security prison as Joaquín "El Chapo" Guzmán, who made a bold escape from that facility in July, exposing a wide web of corruption at the prison (SourceMex, July 15, 2015). -

(Dea) 1985-1990

HISTORY DRUG ENFORCEMENT ADMINISTRATION 1985-1990 New York State, four in California, two in Virginia, and one During the late 1980s, the international drug trafficking each in North Caro-lina and Arizona. One year later, 23 more or-ganizations grew more powerful as the cocaine trade conversion labs were seized in the U.S. dominated the Western Hemisphere. Mafias headquartered in The first crack house had been discovered in Miami in 1982. the Colom-bian cities of Medellin and Cali wielded enormous influence and employed bribery, intimidation, and However, this form of cocaine was not fully appreciated as a major murder to further their criminal goals. Many U.S. threat because it was primarily being consumed by middle class communities were gripped by vio-lence stemming from the users who were not associated with cocaine addicts. In fact, crack drug trade. At first, the most dramatic examples of drug- was initially considered a purely Miami phenomenon until it be related violence were experienced in Miami, where cocaine came a serious problem in New York City, where it first appeared traffickers fought open battles on the city streets. Later, in in December 1983. In the New York City area, it was estimated 1985, the crack epidemic hit the U.S. full force, result-ing in that more than three-fourths of the early crack consumers were escalating violence among rival groups and crack users in many other U.S. cities. By 1989, the crack epidemic was still white professionals or middleclass youngsters from Long Island, raging and drug abuse was considered the most important is suburban New Jersey, or upper-class Westchester County. -

The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) 2009-2013

DRUG ENFORCEMENT ADMINISTRATION HISTORY 2009-2013 Phoenix Drug Kingpin Sentenced to 20 Years for Directing Criminal Enterprise In January 2009, the DEA Phoenix Field Division and the U.S. Attorney for the District of Arizona announced the sentencing of drug kingpin Martin Angel Gonzalez. Martin Angel Gonzalez, 43, of Phoenix, was sentenced to 20 years in prison for operating a large drug trafficking ring out of Phoenix. U.S. District Court Judge Stephen M. McNamee also imposed a $10 million monetary judgment against Gonzalez, who pled guilty to being the leader of a Continuing Criminal Enterprise, Conspiracy to Possess with the Intent to Distribute Marijuana, Conspiracy to Commit Money Laundering, and Possession with the Intent to Distribute Marijuana. Gonzalez was charged with various drug trafficking offenses as part of a 70-count superseding indictment related to his leader ship of a 12-year conspiracy involving the distribution of over 30,000 kilograms of marijuana worth more than $33 million. Twenty-five other co-conspirators were also charged and pled guilty for their involvement in the conspiracy. During the investigation, agents seized approximately 5,000 pounds of marijuana and more than $15 million in organization al assets. These assets included cash, investment accounts, bank accounts, vehicles, jewelry, and real estate properties. Gonzalez’s organization imported marijuana from Mexico, packaged it in the Phoenix area and distributed it to Massachusetts, New York, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Florida, Illinois, Wisconsin, and Califor nia. He distributed marijuana to his associates across the country using commercial trucks, cars and commercial shipping compa nies. Gonzalez was arrested in Morelia, Michoacan, Mexico, with the assistance of Mexican federal law enforcement authorities. -

Capos, Reinas Y Santos - La Narcocultura En México

iMex. México Interdisciplinario. Interdisciplinary Mexico, año 2, n° 3, invierno/winter 2012 Capos, reinas y santos - la narcocultura en México Günther Maihold / Rosa María Sauter de Maihold (UNAM / El Colegio de México; Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, Berlín) En las instalaciones de la Secretaría de la Defensa Nacional, en la capital mexicana, existe desde 1985 el museo probablemente más completo sobre el mundo del narcotráfico. Este narcomuseo, que no está abierto al público, exhibe los procedimientos de producción y distribución de la droga y dispone también de una sala denominada 'Narcocultura' en la que se muestran las joyas, las armas, la vestimenta y los relicarios que les han sido decomisados a los narcotraficantes. La colección ofrece desde una Colt 38 de oro con incrustaciones de esmeraldas, una AK-47 con una palmera de oro en la cacha, una pistola con placas conmemorativas del día de la Independencia en oro, chamarras antibalas y pijamas blindados hasta la vestimenta 'típica', los celulares con marco de oro e incrustaciones de diamantes, relojes de marca con los más inverosímiles y caros adornos, San Judas Tadeo en platino y joyas de incalculable valor. En aras del derroche de riqueza en estos objetos, se podría considerar la narcocultura como una cultura de la ostentación y una cultura del "todo vale para salir de pobre, una afirmación pública de que para qué se es rico si no es para lucirlo y exhibirlo" (Rincón 2012: 2). No obstante, esta cultura de 'nuevos ricos' que inspiran su modus vivendi en el imaginario que tienen de la vida del rico1 posee sus particularidades: es una estética del poder basado en los recursos materiales y simbólicos que manejan, y el mensaje es el de la impunidad, el de encontrarse por encima de la ley y su capacidad de imponer su propio orden y su propia justicia. -

Find Ebook # Mexican Drug Traffickers

P9YPVUBKHGJ0 / Kindle // Mexican drug traffickers Mexican drug traffickers Filesize: 4.54 MB Reviews This publication is really gripping and exciting. It really is basic but unexpected situations in the 50 % in the book. It is extremely difficult to leave it before concluding, once you begin to read the book. (Prof. Salvador Lynch) DISCLAIMER | DMCA MKGOXQF4ALEA ~ PDF // Mexican drug traffickers MEXICAN DRUG TRAFFICKERS Reference Series Books LLC Sep 2012, 2012. Taschenbuch. Book Condition: Neu. 245x189x10 mm. Neuware - Source: Wikipedia. Pages: 38. Chapters: Beltrán-Leyva Cartel traickers, Colima Cartel traickers, Guadalajara Cartel traickers, Gulf Cartel traickers, Juárez Cartel traickers, La Familia Cartel traickers, Los Zetas, Sinaloa Cartel traickers, Sonora Cartel traickers, Tijuana Cartel traickers, Joaquín Guzmán Loera, List of Mexico's 37 most-wanted drug lords, Juan García Abrego, Edgar Valdez Villarreal, Arturo Beltrán Leyva, Amado Carrillo Fuentes, Zhenli Ye Gon, Miguel Ángel Félix Gallardo, Miguel Treviño Morales, Sandra Ávila Beltrán, Heriberto Lazcano Lazcano, Vicente Carrillo Fuentes, Ismael Zambada García, Teodoro García Simental, Héctor Beltrán Leyva, Juan José Esparragoza Moreno, Los Negros, Nazario Moreno González, Jorge Lopez-Orozco, Carlos Beltrán Leyva, Antonio Cárdenas Guillén, Héctor Luis Palma Salazar, Rafael Caro Quintero, Carlos Rosales Mendoza, Miguel Caro Quintero, Sergio Villarreal Barragán, Alfredo Beltrán Leyva, Servando Gómez Martínez, Eduardo Ravelo, Ramón Arellano Félix, Benjamín Arellano Félix, Osiel -

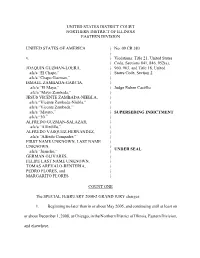

C:\Documents and Settings\Rsamborn\Local Settings

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS EASTERN DIVISION UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ) No. 09 CR 383 ) v. ) Violations: Title 21, United States ) Code, Sections 841, 846, 952(a), JOAQUIN GUZMAN-LOERA, ) 960, 963, and Title 18, United a/k/a “El Chapo,” ) States Code, Section 2. a/k/a “Chapo Guzman,” ) ISMAEL ZAMBADA-GARCIA, ) a/k/a “El Mayo,” ) Judge Ruben Castillo a/k/a “Mayo Zambada,” ) JESUS VICENTE ZAMBADA-NIEBLA, ) a/k/a “Vicente Zambada-Niebla,” ) a/k/a “Vicente Zambada,” ) a/k/a “Mayito,” ) SUPERSEDING INDICTMENT a/k/a “30 ” ) ALFREDO GUZMAN-SALAZAR, ) a/k/a “Alfredillo,” ) ALFREDO VASQUEZ-HERNANDEZ, ) a/k/a “Alfredo Compadre,” ) FIRST NAME UNKNOWN, LAST NAME ) UNKNOWN, ) UNDER SEAL a/k/a “Juancho,” ) GERMAN OLIVARES, ) FELIPE LAST NAME UNKNOWN, ) TOMAS AREVALO-RENTERIA, ) PEDRO FLORES, and ) MARGARITO FLORES ) COUNT ONE The SPECIAL FEBRUARY 2008-2 GRAND JURY charges: 1. Beginning no later than in or about May 2005, and continuing until at least on or about December 1, 2008, at Chicago, in the Northern District of Illinois, Eastern Division, and elsewhere, JOAQUIN GUZMAN-LOERA, a/k/a “El Chapo,” a/k/a “Chapo Guzman,” ISMAEL ZAMBADA-GARCIA, a/k/a “El Mayo,” a/k/a “Mayo Zambada,” JESUS VICENTE ZAMBADA-NIEBLA a/k/a “Vicente Zambada-Niebla,” a/k/a “Vicente Zambada,” a/k/a “Mayito,” a/k/a “30,” ALFREDO GUZMAN-SALAZAR, a/k/a “Alfredillo,” ALFREDO VASQUEZ-HERNANDEZ, a/k/a “Alfredo Compadre,” FIRST NAME UNKNOWN, LAST NAME UNKNOWN, a/k/a “Juancho,” GERMAN OLIVARES, FELIPE LAST NAME UNKNOWN, TOMAS AREVALO-RENTERIA, PEDRO FLORES, -

Drug Trafficking Organizations and Counter- Drug Strategies in the U.S.-Mexican Context Luis Astorga and David A

USMEX WP 10-01 Drug Trafficking Organizations and Counter- Drug Strategies in the U.S.-Mexican Context Luis Astorga and David A. Shirk Mexico and the United States: Confronting the Twenty-First Century This working paper is part of a project seeking to provide an up-to-date assessment of key issues in the U.S.-Mexican relationship, identify points of convergence and diver- gence in respective national interests, and analyze likely consequences of potential policy approaches. The project is co-sponsored by the Center for U.S.-Mexican Studies (San Diego), the Mexico Institute of the Woodrow Wilson Center (Washington DC), El Colegio de la Frontera Norte (Tijuana), and El Colegio de México (Mexico City). Drug Trafficking Organizations and Counter-Drug Strategies in the U.S.-Mexican Context Luis Astorga and David A. Shirk1 “Si la perra está amarrada/ aunque ladre todo el día/ no la deben de soltar/ mi abuelito me decía/ que podrían arrepentirse/ los que no la conocían (…) y la cuerda de la perra/ la mordió por un buen rato/ y yo creo que se soltó/ para armar un gran relajo (…) Los puerquitos le ayudaron/ se alimentan de la Granja/ diario quieren más maíz/ y se pierden las ganancias (…) Hoy tenemos día con día/ mucha inseguridad/ porque se soltó la perra/ todo lo vino a regar/ entre todos los granjeros/ la tenemos que amarrar” As my grandmother always told me, ‘If the dog is tied up, even though she howls all day long, you shouldn’t set her free … and the dog the chewed its rope for a long time, and I think it got loose to have a good time… The pigs helped it, wanting more corn every day, feeding themselves on the Farm and losing profits… Today we have more insecurity every day because the dog got loose, everything got soaked. -

The Drog Trafficking Phenomenom

Contents Introduction…………………………………………………………………………1 Chapter I 1. Drug Trafficking Organizations and their historical context……………3 1.1 Pioneering DTOs and their operational standards. 1.2 Transitional period and the advent of a brand new generation of DTOs. 1.3 The Narco Juniors. 1.4 Nowadays. Chapter II 2. Drug Trafficking Organizations revenues in black and white.................15 2.1 The underlying econom y of the DTOs a) A series of estimates. b) Drug Trafficking as a family enterprise, and regional span. c) Money Laundering. Chapter III 3. Comparative analysis..................................................................................21 3.3 Bolivia. Chapter IV 4. Organized Crime and its economic cycle…………………………………28 a) An analysis from an economic perspective b) Is legalization an option? 5. Conclusions………………………………………………………………..….39 6. Bibliography………………………………………………………..…………42 Introduction The essay you are about to read, tries to explain the rising development and growth of the organized crime in Mexico, how it came to be, grow, collision and mutate. Being as is a criminal phenomenon, wherein different players reap benefits, an economic perspective is necessary, pinpointing the estimated profits and revenues of organized crime. Likewise, we refer to the evolution of one of the countries that amazingly enough is one of tradition when it comes to production and consumption of narcotics: Bolivia, which had an apparently successful eradication experience for some years, by implementing public policies that managed to change coca leaf producer activities, though today a former coca leaf producer union leader rules the country. On the last chapter of this essay, a reflection is made in order to reinforce, redirect the anti drug trafficking policy implemented by the federal government, pondering on a new economic approach that might be given to criminal law, analyzing the drivers that lie behind organized crime. -

The U.S. Homeland Security Role in the Mexican War Against Drug Cartels”

STATEMENT OF THOMAS M. HARRIGAN ASSISTANT ADMINISTRATOR AND CHIEF OF OPERATIONS DRUG ENFORCEMENT ADMINISTRATION BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT, INVESTIGATIONS AND MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES AT A HEARING ENTITLED “THE U.S. HOMELAND SECURITY ROLE IN THE MEXICAN WAR AGAINST DRUG CARTELS” PRESENTED MARCH 31, 2011 STATEMENT FOR THE RECORD OF THOMAS M. HARRIGAN ASSISTANT ADMINISTRATOR AND CHIEF OF OPERATIONS DRUG ENFORCEMENT ADMINISTRATION BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT, INVESTIGATIONS AND MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ENTITLED “THE U.S. HOMELAND SECURITY ROLE IN THE MEXICAN WAR AGAINST DRUG CARTELS” PRESENTED MARCH 31, 2011 INTRODUCTION Drug trafficking and abuse exacts a significant toll on the American public. More than 31,000 Americans – or approximately ten times the number of people killed by terrorists on September 11, 2001, die each year as a direct result of drug abuse. Approximately seven million people who are classified as dependent on, or addicted to, controlled substances squander their productive potential. Many of these addicts neglect or even abuse their children and/or commit a variety of crimes under the influence of, or in an attempt to obtain, illicit drugs. Tens of millions more suffer from this supposedly “victimless” crime, as law-abiding citizens are forced to share the roads with drivers under the influence of drugs, pay to clean up toxic waste from clandestine laboratories, rehabilitate addicts, and put together the pieces of shattered lives. In truth, in order to calculate an actual cost of this threat, we must explore and examine the impact produced by transnational drug crime in corrupting government institutions, undermining public confidence in the rule of law, fostering violence, fueling regional instability, and funding terrorism.