Cebu City's Colon Street: Curating Frames Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Investigating the Nighttime Urban Heat Island (Canopy Layer) Using Mobile Traverse Method: a Case Study of Colon Street in Cebu City, Philippines

POLLACK PERIODICA An International Journal for Engineering and Information Sciences DOI: 10.1556/606.2017.12.3.10 Vol. 12, No. 3, pp. 109–116 (2017) www.akademiai.com INVESTIGATING THE NIGHTTIME URBAN HEAT ISLAND (CANOPY LAYER) USING MOBILE TRAVERSE METHOD: A CASE STUDY OF COLON STREET IN CEBU CITY, PHILIPPINES 1Rowell Ray Lim SHIH, 2István KISTELEGDI 1 University of San Carlos, Cebu, Philippines, e-mail: [email protected] 2 Department of Building Structures and Energy Design, Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology, University of Pécs, Boszorkány u. 2, H-7624 Pécs, Hungary e-mail: [email protected] Received 8 August 2016; accepted 21 April 2017 Abstract: Rapid urbanization has resulted in temperature differences between the urban area and its surrounding areas. Academics have called this as the urban heat island phenomenon. Among the places that have seen rapid urbanization is the City of Cebu. The Philippine’s oldest street, Colon, was chosen as the study area due to the near absence of vegetation and closely spaced buildings. Buildings that are spaced more closely as well as multiple absorptions and reflections produce higher and more viable street temperatures. This study tries to systematically understand the urban heat island effect between Colon and Lawaan, the rural area defined in this study. In order to quantify the urban heat island between two given locations, the mobile traverse method during the summer time, for a 10-day period in May 2016. A digital thermometer measuring platform was mounted on top of a vehicle to measure the different temperatures of Colon Street. Urban temperatures were also gathered in the Lawaan area using the same device. -

List of Participating Petron Service Stations September 6

LIST OF PARTICIPATING PETRON SERVICE STATIONS SEPTEMBER 6 - 21, 2021 REGION CITY / MUNICIPALITY ADDRESS METRO MANILA CALOOCAN CITY 245 SUSANO ROAD, DEPARO KALOOKAN CITY METRO MANILA CALOOCAN CITY ZABARTE ROAD, BRGY. CAMARIN, NORTH CALOOCAN, KALOOKAN CITY METRO MANILA CALOOCAN CITY 146RIZAL AVENUE EXT. GRACE PARK CALOOCAN CITY METRO MANILA CALOOCAN CITY 510 A. MABINI ST., KALOOKAN CITY METRO MANILA CALOOCAN CITY C-3 ROAD, DAGAT-DAGATAN CALOOCAN CITY METRO MANILA CALOOCAN CITY BLK 46 CONGRESSIONAL ROAD EXT., BAG CALOOCAN CITY METRO MANILA CALOOCAN CITY B. SERRANO ST. COR 11TH AVE CALOOCAN CITY METRO MANILA CALOOCAN CITY GEN. SAN MIGUEL ST., SANGANDAAN, CALOOCAN CITY METRO MANILA LAS PINAS ALABANG ZAPOTE ROAD LAS PINAS, METRO MANILA METRO MANILA LAS PINAS LOT 2A DAANG HARI CORNER DAANG REYN LAS PINAS METRO MANILA LAS PINAS NAGA ROAD LAS PINAS CITY, METRO MANILA METRO MANILA LAS PINAS BLK 14 LOT 1 VERSAILLES SUBD DAANG LAS PIбAS CITY METRO MANILA LAS PINAS CRM AVENUE, BF ALMANZA, LAS PIбAS METRO MANILA METRO MANILA LAS PINAS LOT 1 & 2 J. AGUILAR AVENUE TALON TRES, LAS PINAS METRO MANILA LAS PINAS ALABANG ZAPOTE RD., PAMPLONA LAS PINAS METRO MANILA LAS PINAS 269 REAL ST. PAMPLONA LAS PINAS METRO MANILA LAS PINAS 109 MARCOS ALVAREZ AVE. TALON LAS PINAS METRO MANILA LAS PINAS 469 REAL ST., ZAPOTE LAS PINAS METRO MANILA MAKATI CITY 46 GIL PUYAT AVE. NEAR COR. DIAN MAKATI CITY METRO MANILA MAKATI CITY G PUYAT COR P TAMO AVE, MAKATI CITY METRO MANILA MAKATI CITY LOT 18 BLOCK 76 SEN. GIL PUYAT AVE. PALANAN, MAKATI CITY METRO MANILA MAKATI CITY PETRON DASMARINAS STATION EDSA, MAKATI CITY METRO MANILA MAKATI CITY 363 SEN. -

Cebu 1(Mun to City)

TABLE OF CONTENTS Map of Cebu Province i Map of Cebu City ii - iii Map of Mactan Island iv Map of Cebu v A. Overview I. Brief History................................................................... 1 - 2 II. Geography...................................................................... 3 III. Topography..................................................................... 3 IV. Climate........................................................................... 3 V. Population....................................................................... 3 VI. Dialect............................................................................. 4 VII. Political Subdivision: Cebu Province........................................................... 4 - 8 Cebu City ................................................................. 8 - 9 Bogo City.................................................................. 9 - 10 Carcar City............................................................... 10 - 11 Danao City................................................................ 11 - 12 Lapu-lapu City........................................................... 13 - 14 Mandaue City............................................................ 14 - 15 City of Naga............................................................. 15 Talisay City............................................................... 16 Toledo City................................................................. 16 - 17 B. Tourist Attractions I. Historical........................................................................ -

69Th Issue Jan. 11

“Radiating positivity, creating connectivity” CEBU BUSINESS Room 310-A, 3rd floor WDC Bldg. Osmeña Blvd., Cebu City You may visit Cebu Business Week WEEK Facebook page. January 11 - 17, 2021 Volume 3, Series 69 www.cebubusinessweek.com 12 PAGES P15.00 SEAFARERS GIVE ECONOMY P300B 500K working in international vessels despite pandemic: Marino OVER half million Filipino Seafarers with big income By: ELIAS O. BAQUERO ping is unhampered even if He said that in the data seafarers are working continu- and having new families are there is Covid-19 pandemic,” of the Philippine Overseas ously around the world con- mostly investing in the busi- jected to a 14-day quarantine, Lusotan said. Employment Administration tributing to the economy some ness of their choice or keep and other health protocols. Lusotan said about that (POEA), there are more than US$6.5 million, equivalent to big savings in banks, and the The seafarers who are there are more than 3,000 two million Overseas Filipino P300 billion despite the pan- banks are lending capital to affected are those who are seafarers who are waiting to Workers (OFWs) around the demic, said Marino Party-List Micro, Small and Medium En- waiting to replace their coun- be called to board the vessels, world. The highest numbers of Rep. Macnell Lusotan. terprises (MSMEs). terparts who are on board ves- but because of the pandemic, OFWs are in the Middle East. Lusotan told Cebu Busi- Most Filipino seafarers sels and who choose to extend they are stranded in Manila, Of the two million, 25 percent ness Week that the Filipino abroad only problem is their their contract because of the some of whom are living with or 500,000 are seafarers. -

Tradename Bayad Center Name Address Town/City Province Area Region Txn Type

BAYAD CENTER TXN TYPE TRADENAME ADDRESS TOWN/CITY PROVINCE AREA REGION NAME (CICO) 13SIBLINGS 13SIBLINGS COR ANTERO SORIANO GENERAL LOGISTICS LOGISTICS HIWAY,CENTENNIAL RD. & CAVITE SOL REGION IV - A Cash in only TRIAS SERVICES SERVICES GEN TRIAS, CAVITE BAYAD CENTER - 3056 A. REDEMPTORIST 2AV PAYMENT PARAÑAQUE METRO REDEMPTORIST, ROAD, BACLARAN, GMM NCR Cash in only CENTER CITY MANILA BACLARAN PARAÑAQUE CITY 3 AJ BAYAD MASSWAY SUPERMARKET BAYAD CENTER - CENTER - BRGY BINAKAYAN, KAWIT KAWIT CAVITE SOL REGION IV - A Cash in only MASSWAY MASSWAY CAVITE 888 CASHER BLOCK 17, L17, STALL 1, BAYAD CENTER - LAS PIÑAS METRO CORPORATION - DONNA AGUIRRE AVE. PILAR, GMM NCR Cash in only PILAR VILLAGE CITY MANILA PILAR LAS PIÑAS CITY BLK 9 LOT 22 PINAGSAMA AGINAYA BAYAD CENTER - METRO VILLAGE PHASE 2, TAGUIG TAGUIG CITY GMM NCR Cash in only ENTERPRISE PINAGSAMA MANILA CITY AJM BUSINESS AJM BUSINESS PUROK 13, DAMILAG, MANOLO CENTER & I.T. CENTER & I.T. MANOLO FORTICH, BUKIDNON MIN REGION X Cash in only FORTICH SERVICES SERVICES BUKIDNON ALAINA JEM BAYAD CENTER - G/F RFC MOLINO MALL, TRAVEL RFC MOLINO BACOOR CAVITE SOL REGION IV - A Cash in only MOLINO BACOOR, CAVITE SERVICES MALL GROUND FLOOR, RUSTANS ALAINA JEM BAYAD CENTER - SUPERMARKET, VISTA MALL LAS PIÑAS METRO TRAVEL GMM NCR Cash in only EVIA EVIA, DAANG HARI ROAD, CITY MANILA SERVICES - EVIA LAS PINAS CITY GROUND FLOOR SERVICE AREA, FESTIVAL MALL, ALTERNATE BAYAD CENTER - COMMERCE AVENUE MUNTINLUP METRO REALITIES - GMM NCR Cash in only FESTIVAL MALL FILINVEST CORPORATE CITY, A CITY MANILA FESTIVAL MALL ALABANG, MUNTINLUPA CITY 1-E NOVA SQUARE QUIRINO AMZ BAYAD BAYAD CENTER - HWAY COR. -

Building a Strong Platform for Recovery, Renewed

2020 INTEGRATED REPORT BUILDING A STRONG PLATFORM FOR RECOVERY, RENEWED GROWTH, AND RESILIENCE Ayala Land’s various initiatives on stakeholder support, investment, and reinvention pave the way for recovery PAVING THE WAY FOR RECOVERY AND SUSTAINABLE GROWTH The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and the natural calamities that of digital platforms to reach and engage buyers. Staff of APMC, struck the Philippines in 2020 are still being felt by Filipinos to this the company’s property management firm, stayed-in its managed day. Ayala Land’s swift response to face these challenges showed properties and communities while the enhanced community the resilience of both the company and its people. quarantine was enforced. In a strategic pivot, ALIzens executed a five-point action plan— Helping the Community protecting the workforce, financial sustainability, serving customers, Ayala Land employees raised PHP82.6 million under the Ayala helping the community, and thinking ahead towards recovery. Land Pays It Forward campaign to provide medical supplies and This action plan enabled Ayala Land, its employees, and its personal protective equipment to three COVID-19 designated communities to withstand the challenges and position for recovery. treatment hospitals. The company helped raise PHP425 million for Project Ugnayan and allocated PHP600 million in financial With the continued trust and confidence of its shareholders and assistance to more than 70 thousand “no work-no pay” contingent stakeholders, Ayala Land will count on bayanihan (community personnel during the critical first weeks of the quarantine. spirit) to move forward and pave the way for recovery and Recognizing the difficulties of its mall merchants, Ayala Land sustainable growth. -

CEBU | OFFICE 1Q 2018 9 March 2018

Colliers Bi-Annual CEBU | OFFICE 1Q 2018 9 March 2018 Offshore Forecast at a glance Demand Total office transactions reached nearly gambling rises 107,000 sq m (1.2 million sq ft) in 2017. Offshore gambling is an emerging office Joey Roi Bondoc Research Manager segment and we see greater absorption from this sector over the next two to three years. The continued demand from Offshore gambling is emerging as a critical segment BPO and KPO firms should support at of the Cebu office market as it accounted for almost least a 10% annual growth in 25% of recorded transactions in 2017. Business transactions until 2020. Process Outsourcing(BPO)-Voice companies continue to dominate covering more than a half of Supply transactions while the Knowledge Process We see Cebu's office stock breaching Outsourcing (KPO) firms that provide higher value the 1 million sq m (10.8 million sq ft) services also sustained demand, taking 20% of the mark this year. Between 2018 and 2020, total office leases. Colliers sees the current we expect the completion of close to administration's infrastructure implementation and 400,000 sq m (4.3 million sq ft) of new office space. A combined 60% of the decentralization thrust benefiting Cebu as it is the new supply will be in Cebu Business largest business destination outside Metro Manila. Park (CBP) and Cebu IT Park (CITP). This should entice more offshore gambling, BPO, KPO and traditional firms to set up shop or expand Vacancy rate operations. We encourage both landlords and Overall vacancy in Cebu stood at 9.7% tenants to as of end-2017.This is lower than the 12% recorded at end-2016. -

Paylink Merchants 2005

LIST OF AFFILIATED MERCHANTS Count Merchant No. Legal Name DBA Name Address1 Address 2 City Area Code / Desc 1 181933 ABENSON, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (ALABANG) TIERRA NUEVA SUBD. ALABANG MUNTINLUPA 33 - MUNTINLUPA 2 1117761 ABENSON, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (BULACAN) IS PAVILIONS MEYCAUAYAN 58 - BULACAN 3 181834 ABENSON, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (CALOOCAN) RIZAL AVE. EXT. CALOOCAN CALOOCAN CITY 28 - CALOOCAN 4 1117167 WALTER MART STA ROSA, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (DASMARINAS) WALTERMART, KM 30 BO BUROL AGUINALDO DASMARINAS 59 - CAVITE 5 290288 ABENSON, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (ERMITA) 3/F ROBINSONS PLACE ERMITA MANILA 20 - MANILA 6 231852 ABENSON, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (EVER ORTIGA G/F EVER GOTESCO ORTIGAS AVE., STA. LUCIA, PASIG CITY PASIG CITY 25 - PASIG 7 231878 ABENSON, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (FARMER'S) FARMER'S PLAZA CUBAO QUEZON CITY 21 - QUEZON CITY 8 182485 ABENSON, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (GALLERIA) ORTIGAS AVE., QUEZON CITY QUEZON CITY 21 - QUEZON CITY 9 182469 ABENSON, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (GREENHILLS) UNIMART SUPERMART GREENHILLS SAN JUAN, METRO MANILA SAN JUAN 23 - SAN JUAN 10 181917 ABENSON, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (HARRISON) 1ST FLR. HARRISON PLAZA COMML. VITO CRUZ, MALATE MANILA 20 - MANILA 11 182501 ABENSON, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (LAS PINAS) 269 ALABANG ZAPOTE ROAD PAMPLONA LAS PINAS 32 - LAS PINAS 12 289397 ABENSON, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (METROPOLIS) G/F MANUELA METROPOLIS ALABANG MUNTINLUPA 33 - MUNTINLUPA 13 181875 ABENSON INCORPORATED ABENSON - PAYLINK (QUAD) QUAD I, MCC . MAKATI CITY 22 - MAKATI 14 181768 ABENSON, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (SHERIDAN) 11 SHERIDAN ST., MANDALUYONG MANDALUYONG 24 - MANDALUYONG 15 181859 ABENSON, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (SM CITY) SM CITY NORTH EDSA QUEZON CITY QUEZON CITY 21 - QUEZON CITY 16 181784 ABENSON, INC. -

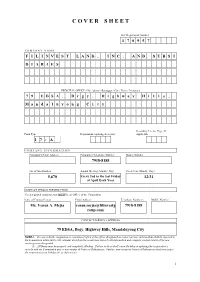

Fli 17A 2019

C O V E R S H E E T SEC Registration Number 1 7 0 9 5 7 C O M P A N Y N A M E F I L I N V E S T L A N D , I N C . A N D S U B S I D I A R I E S PRINCIPAL OFFICE ( No. / Street / Barangay / City / Town / Province ) 7 9 E D S A , B r g y . H i g h w a y H i l l s , M a n d a l u y o n g C i t y Secondary License Type, If Form Type Department requiring the report Applicable 1 7 - A C O M P A N Y I N F O R M A T I O N Company’s Email Address Company’s Telephone Number Mobile Number 7918-8188 No. of Stockholders Annual Meeting (Month / Day) Fiscal Year (Month / Day) 5,670 Every 2nd to the last Friday 12/31 of April Each Year CONTACT PERSON INFORMATION The designated contact person MUST be an Officer of the Corporation Name of Contact Person Email Address Telephone Number/s Mobile Number Ms. Venus A. Mejia venus.mejia@filinvestg 7918-8188 roup.com CONTACT PERSON’s ADDRESS 79 EDSA, Brgy. Highway Hills, Mandaluyong City NOTE 1 : In case of death, resignation or cessation of office of the officer designated as contact person, such incident shall be reported to the Commission within thirty (30) calendar days from the occurrence thereof with information and complete contact details of the new contact person designated 2 : All Boxes must be properly and completely filled-up. -

51St International Eucharistic Congress

51st International Eucharistic Congress • 8-Day Pilgrimage to Cebu • Date: January 27 – February 3, 2016 • Flight schedule: From Taiwan: 1.27.2016 (Wednesday) China Airlines CI 711 7:50 – 09:30 Kaohsiung – Manila Cebu Pacific Airlines 5J 565 12:10 – 13:30 Manila – Cebu From Cebu: 2.3.2016 (Wednesday) Cebu Pacific Airlines 5J 580 12:15 – 13:30 Cebu – Manila China Airlines CI 704 16:55 – 18:55 Manila - Taipei • Itinerary Day 1 January 27 (Wednesday): Kaohsiung – Manila – Cebu Afternoon: Sto. Nino of Cebu Minor Basilica, Magellan’s Cross Accommodation for Jan. 27-31, Feb. 2: Quest Hotel and Conference Center or Waterfront Hotel or Crown Regency Hotel and Towers. All breakfasts are served in this hotel. Day 2 January 28 (Thursday) 8:00 - 8:30 AM Preliminaries 3:00 - 5:00 Penitential Service 8:30 - 9:00 Morning Prayers 7:00 - 10:00 Visita Iglesia: 7 Churches 9:00 - 10:00 Catechesis Youth Day 10:00 - 10:30 Testimony 2:00 - 3:00 Praise and Worship 10:30 - 11:00 BREAK Catechesis 11:00 - 12:30 PM Holy Eucharist 4:00 - 6:00 Transfer to Plaza 12:30 - 2:00 Lunch Break Independencia 2:00 - 3:00 Press Conference with 7:00 - 4:00 AM Overnight Vigil at Plaza Speakers Independencia 2:00 - 4:00 Deaf Tracks 1 & 2 5:00 Holy Eucharist Day 3 January 29 (Friday) 8:00 - 8:30 AM Preliminaries 1:00 - 2:00 Press Conference with the 8:30 - 9:00 Morning Prayers Speakers 9:00 - 10:00 Catechesis 2:00 - 3:00 Deaf Track 3 10:00 - 10:30 Testimony 2:00 - 4:00 Departure for Cebu 10:30 - 11:00 BREAK Capitol Bldg. -

PHILIPPINES MARINE SPECIAL ECONOMIC ZONE PAMPANGA EXPORT PROCESSING ZONE up SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY PARK (North) GREENFIELD AUTOMOTIVE PARK STA

“OPPORTUNITIES FOR KOREAN INVESTORS IN PHILIPPINE ECONOMIC ZONES” A presentation for the: PHILIPPINE INVESTMENT SEMINAR by LILIA B. DE LIMA Director General, PEZA and Undersecretary, Department of Trade and Industry 22/F Diamond Hall, The Plaza Hotel, Seoul, Korea 10:00 AM, May 7, 2013 “OPPORTUNITIES FOR KOREAN INVESTORS IN PHILIPPINE ECONOMIC ZONES” A presentation for the: PHILIPPINE INVESTMENT SEMINAR by LILIA B. DE LIMA Director General, PEZA and Undersecretary, Department of Trade and Industry Guest House, Hanyang University, Ansan, Korea 10:00 AM, May 8, 2013 Philippine Economic Zone Authority An investment promotion and incentive granting agency attached to the Department of Trade and Industry. Reinforce Government’s efforts to: • Promote Investments • Create Employment • Generate Exports 16 EPZA- REGISTERED PUBLIC & PRIVATE ECONOMIC ZONES ( 1969 - 1994) LUISITA INDUSTRIAL PARK SUBIC SHIP. ENG’G. INC. BAGUIO EPZ VICTORIA WAVE CARMELRAY DEV’T. CORP. BATAAN EPZ GATEWAY BUSINESS PARK CAVITE EPZ LIGHT IND. & SCIENCE PARK LAGUNA TECHNOPARK LAGUNA INT’L. IND’L PARK MACTAN EPZ TABANGAO SPECIAL EPZ FIRST CAVITE IND’L. ESTATE LEYTE IND’L. DEV’T ESTATE MACTAN ECOZONE II Total Area : 3,183 hectares TOTAL OF 281 ECONOMIC ZONES * BAGUIO CITY ECONOMIC ZONE MARVIN PLAZA BUILDING 3OOD TERMINAL INC. SEZ JOHN HAY SPECIAL TOURISM ECONOMIC ZONE DPC PLACE BUILDING as of 31 March 2013 EMI SPECIAL ECOZONE SANCTUARY IT BUILDING MSE CENTER BATAAN ECONOMIC ZONE CAVITE ECONOMIC ZONE SM BAGUIO CYBERZONE BUILDING TRAFALGAR PLAZA SUBIC SHIPYARD LAGUNA INT’L. INDUSTRIAL PARK FORT ILOCANDIA TOURISM ECONOMIC ZONE OCTAGON IT BUILDING PLASTIC PROCESSING CENTER SEZ LIGHT INDUSTRY & SCIENCE PARK I PANGASINAN INDUSTRIAL PARK II VITRO INTERNET DATA CENTER BUILDING HERMOSA ECOZONE LIGHT INDUSTRY & SCIENCE PARK II LUISITA INDUSTRIAL PARK WYNSUM CORPORATE PLAZA IT BUILDING LEYTE IND’L. -

Cebuano-Culture.Pdf

Table of Contents Chapter 1 Profile................................................................................................................. 5 Introduction..................................................................................................................... 5 Area and Climate ............................................................................................................ 5 Major Cities ....................................................................................................................6 Cebu City .................................................................................................................... 6 Danao City .................................................................................................................. 7 Lapu-Lapu City........................................................................................................... 7 Mandaue City.............................................................................................................. 8 Talisay City................................................................................................................. 8 Toledo City ................................................................................................................. 8 Major Rivers ................................................................................................................... 8 Guadalupe and Mahiga Rivers.................................................................................... 9 Buhisan River.............................................................................................................