CHAPTER 20 - Lesa Ni Mhunghaile 10/7/15 3:07 PM Page 547

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1.1 Employment Sectors

1.1 EMPLOYMENT SECTORS To realise the economic potential of the Gateway and identified strategic employment centres, the RPGs indicates that sectoral strengths need be developed and promoted. In this regard, a number of thematic development areas have been identified, the core of which are pivoted around the main growth settlements. Food, Tourism, Services, Manufacturing and Agriculture appear as the primary sectors being proffered for Meath noting that Life Sciences, ICT and Services are proffered along the M4 corridor to the south and Aviation and Logistics to the M1 Corridor to the east. However, Ireland’s top 2 exports in 2010, medical and pharmaceutical products and organic chemicals, accounted for 59% of merchandise exports by commodity group. It is considered, for example, that Navan should be promoted for medical products noting the success of Welch Allyn in particular. An analysis has been carried out by the Planning Department which examined the individual employment sectors which are presently in the county and identified certain sectoral convergences (Appendix A). This basis of this analysis was the 2011 commercial rates levied against individual premises (top 120 rated commercial premises). The analysis excluded hotels, retail, public utilities public administration (Meath County Council, OPW Trim and other decentralized Government Departments) along with the HSE NE, which includes Navan Hospital. The findings of this analysis were as follows: • Financial Services – Navan & Drogheda (essentially IDA Business Parks & Southgate Centre). • Industrial Offices / Call Centres / Headquarters – Navan, Bracetown (Clonee) & Duleek. • Food and Meath Processing – Navan, Clonee and various rural locations throughout county. • Manufacturing – Oldcastle and Kells would have a particular concentrations noting that a number of those with addresses in Oldcastle are in the surrounding rural area. -

Minerals Development Acts, 1940–1999

MINERALS DEVELOPMENT ACTS, 1940–1999 Report by the Minister of the Environment, Climate and Communications for the six months ended 30 June 2021 In accordance with Section 77 of the Minerals Development Act, 1940 And Section 8 of the Minerals Development Act, 1979 Prepared by the Geoscience Regulation Office Department of the Environment, Climate and Communications www.gov.ie/decc Department of the Environment, Climate and Communications Minerals Development Acts, 1940-1999 Report by the Minister for the Environment, Climate and Communications for the six months ended 30 June 2021 In accordance with Section 77 of the Minerals Development Act, 1940 and Section 8 of The Minerals Development Act, 1979 Geoscience Regulation Office Minerals Production MP 04/21 _______________________________________ Dublin Published by the Stationery Office To be purchased from Government Publications 52 St. Stephen's Green, Dublin, D02 DR67. (Tel: 076 1106 834 or Email: [email protected]) or through any bookseller. This report may also be found on the Internet at www.gov.ie where it was posted shortly after it’s presentation to the Oireachtas _______________________________________ Sale Price: €12.70 © Government of Ireland 2021 An Roinn Comhshaoil, Aeráide agus Cumarsáide Na hAchtanna Forbartha Mianraí, 1940-1999 Tuarascáil an Aire Comhshaoil, Aeráide agus Cumarsáide don sé mhí dár críoch 30 Meitheamh 2021 De réir Alt 77 den Acht Forbairte Mianraí, 1940 agus Alt 8 den Acht Forbartha Mianraí, 1979 Oifig Rialacháin Geo-Eolaíochta Táirgeadh Mianraí MP 04/21 _______________________________________ Baile Átha Cliath Arna Fhoilsiú ag Oifig an tSoláthair Le ceannach díreach ó Foilseacháin Rialtais 52 Faiche Stiabhna, Baile Átha Cliath, D02 DR67. -

LMETB Land and Buildings Insight

LAND AND BUILDINGS INSIGHT Foreword I am pleased to present an insight into the activity of LMETB’s Land and Buildings The Board of LMETB has played a crucial role in I want to bring your attention to a very innovative Department. With increased enrolments, successful patronage campaigns for supporting the collective achievements of LMETB development occurring in LMETB, namely our and I would like to acknowledge its contribution, in new Advanced Manufacturing Training Centre of new schools and rapidly expanding Further Education and Training provision, particular the members of the Land and Buildings Excellence in Dundalk which was the brainchild of there has been a significant expansion of associated capital projects over the Sub-Committee. The membership of the Land our Chief Executive. More on that later…!! past number of years. This overview will give the reader an appreciation of the and Buildings Sub-Committee comprises Mr. Bill Sweeney (Chair), Cllr. Sharon Tolan, Cllr. Nick The Land and Buildings Department has many projects currently being delivered by the Land and Buildings Team and a Killian, Cllr. Maria Murphy, Cllr, John Sheridan and established and maintained excellent working preview of what is planned for 2021. These are exciting times for LMETB as we Cllr. Antoin Watters. LMETB has made governance relationships with key stakeholders. This, coupled commence a whole host of new projects across Louth and Meath. a key priority and our Land and Buildings Sub- with LMETBs vision and experience allows us Committee is tasked with very detailed “Terms deliver state of the art capital projects within of Reference”. -

This Is Your Rural Transport! Evening Services /Community Self-Drive to Their Appointment

What is Local Link? CURRENT SERVICE AREAS Local Link (formerly “Rural Transport”) is a response by the government to the lack of public transport in rural areas. Ardbraccan, Ardnamagh, Ashbourne, Athboy, Flexibus is the Local link Transport Co-ordination Unit that Baconstown, Bailieborough, Ballinacree, Ballivor, manages rural transport in Louth Meath & Fingal. Balrath, Baltrasa, Barleyhill, Batterstown, Services available for: Beauparc, Bective, Bellewstown, Bloomsberry, Anyone in rural areas with limited access to shopping, Bohermeen, Boyerstown, Carlanstown, banking, post office, and social activities etc. Carrickmacross, Castletown, Clonee, Clonmellon, regardless of age. Crossakiel, Collon, Connells Cross, Cormeen, People who are unable to get to hospital appointments. Derrlangan, Dowth, Drogheda, Drumconrath, People with disabilities / older people who need accessible transport. Drumond, Duleek, Dunboyne, Dunsany, Self Drive for Community Groups. Dunshaughlin, Gibbstown, Glenboy, Grennan, Harlinstown, Jordanstown, Julianstown, Advantages of Local Link services Kells, Kentstown, Kilberry, Kildalkey, Services are for everyone who lives in the local area Kilmainhamwood, Kingscourt, Knockbride, We accept Free Travel Pass or you can pay. Information We pick up door to door on request. Knockcommon, Lisnagrow, Lobinstown, Services currently provided are the services your Longwood, Milltown, Mountnugent, Moyagher, on all Flexibus community has told us you need! Moylagh, Moynalty, Moynalvy, Mullagh, If a regular service is needed -

Age Friendly Ireland 51

ANNUAL REPORT 2020 Contents Foreword 1 Highlights 2020 2 Corporate Services 4 Housing 17 Planning and Development 22 Heritage 22 Road Transportation and Safety 26 Environment, Fire and Emergency Services 33 Community 42 Age Friendly Ireland 51 Library Services 55 Arts Office 58 Economic Development and Enterprise 64 Tourism 66 Water Services 70 Finance 72 Human Resources 74 Information Systems 78 Appendix 1 – Elected Members Meath County Council 80 Appendix 2 – Strategic Policy Committee (SPC) Members 81 Appendix 3 – SPC Activities 83 Appendix 4 – Other Committees of the Council 84 Appendix 5 – Payments to Members of Meath County Council 89 Appendix 6 – Conferences Abroad 90 Appendix 7 - Conferences/Training at Home 91 Appendix 8 – Meetings of the Council – 2020 93 Appendix 9 – Annual Financial Statement 94 Appendix 10 – Municipal District Allocation 2020 95 Appendix 11 – Energy Efficiency Statement 2019 98 This Annual Report has been prepared in accordance with Section 221 of the Local Government Act and adopted by the members of Meath County Council on June 14, 2021. Meath County Council Annual Report 2020 Foreword We are pleased to present Meath County Council’s Annual Report 2020, which outlines the achievements and activities of the Council during the year. It was a year dominated by the COVID pandemic, which had a significant impact on the Council’s operating environment and on the operations of the Council and the services it delivers. Despite it being a year like no other, the Council continued to deliver essential and frontline local services and fulfil its various statutory obligations, even during the most severe of the public health restrictions. -

Bellasis Presbyterian Church, Co. Cavan

Bellasis Presbyterian Church, Co. Cavan Baptisms 1833 – 1985; Marriages 1845 – 1951 No burials listed* [PRONI MIC/1P/267] *but see listings from graveyard below * This file updated 21.07.2019 Marriages When Name & Age Condition Rank or Residence at Father’s Rank or married Surname Profession time of Name Profession marriage 07 John Byars full age Bachelor Farmer Lataster John Byars Farmer July 1845 Anne Fagan full age Spinster - Crankree The late Farmer ? Fagan Witnesses were William Hogg James Byars NB: The Civil Register gives Letester and Cremlin in Column 6; and states “Drumgora, Meeting House of Bellasis”. The late Mr Fagan’s Christian name is obscure in both sources. It might be Hu[gh]. 18 Josias Wilson full age Bachelor Farmer Donena, William Wilson Farmer September Parish of 1845 Bailieboro’ Anne Byars full age Spinster - Tievenaman, Robert Byars Farmer Parish of Killinkere Witnesses were George Jameson George Brown 11 James Coote full age Widower Farmer Dromore, Thomas Coote Farmer December Parish of 1845 Bailieboro’ Jane Coote full age Spinster - Killaduff, The late Farmer Parish of William Coote Killiker 21 Alex Stafford jun. full age Widower Farmer Carrickmore Ben. Stafford Farmer January 1846 Lydia Byars 15 years Spinster - Tievenaman Samuel Byars Farmer (Civil Register gives Byers) Witnesses were George Jameson James Stafford When Name & Age Condition Rank or Residence at Father’s Rank or married Surname Profession time of Name Profession marriage 18 Thos. McIlwain full age Bachelor Farmer Lisanymore The late Saml. Farmer February McIlwain 1846 Jane Harrison 19 years Spinster - Drumagoland William Farmer Harrison Witnesses were George Jameson George McQuade (X his mark) 1 11 Thomas Watson full age Widower Farmer Fintavin James Watson Farmer June 1846 Sarah McIlwain full age Spinster - Lisnamore Thomas Farmer McIlwain Witnesses were Samuel McIlwain Robt. -

Irish Wildlife Manuals No. 103, the Irish Bat Monitoring Programme

N A T I O N A L P A R K S A N D W I L D L I F E S ERVICE THE IRISH BAT MONITORING PROGRAMME 2015-2017 Tina Aughney, Niamh Roche and Steve Langton I R I S H W I L D L I F E M ANUAL S 103 Front cover, small photographs from top row: Coastal heath, Howth Head, Co. Dublin, Maurice Eakin; Red Squirrel Sciurus vulgaris, Eddie Dunne, NPWS Image Library; Marsh Fritillary Euphydryas aurinia, Brian Nelson; Puffin Fratercula arctica, Mike Brown, NPWS Image Library; Long Range and Upper Lake, Killarney National Park, NPWS Image Library; Limestone pavement, Bricklieve Mountains, Co. Sligo, Andy Bleasdale; Meadow Saffron Colchicum autumnale, Lorcan Scott; Barn Owl Tyto alba, Mike Brown, NPWS Image Library; A deep water fly trap anemone Phelliactis sp., Yvonne Leahy; Violet Crystalwort Riccia huebeneriana, Robert Thompson. Main photograph: Soprano Pipistrelle Pipistrellus pygmaeus, Tina Aughney. The Irish Bat Monitoring Programme 2015-2017 Tina Aughney, Niamh Roche and Steve Langton Keywords: Bats, Monitoring, Indicators, Population trends, Survey methods. Citation: Aughney, T., Roche, N. & Langton, S. (2018) The Irish Bat Monitoring Programme 2015-2017. Irish Wildlife Manuals, No. 103. National Parks and Wildlife Service, Department of Culture Heritage and the Gaeltacht, Ireland The NPWS Project Officer for this report was: Dr Ferdia Marnell; [email protected] Irish Wildlife Manuals Series Editors: David Tierney, Brian Nelson & Áine O Connor ISSN 1393 – 6670 An tSeirbhís Páirceanna Náisiúnta agus Fiadhúlra 2018 National Parks and Wildlife Service 2018 An Roinn Cultúir, Oidhreachta agus Gaeltachta, 90 Sráid an Rí Thuaidh, Margadh na Feirme, Baile Átha Cliath 7, D07N7CV Department of Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht, 90 North King Street, Smithfield, Dublin 7, D07 N7CV Contents Contents ................................................................................................................................................................ -

Site at Eastham Road, Bettystown, Co Meath

SITE AT EASTHAM ROAD, BETTYSTOWN, CO MEATH FOR SALE BY PRIVATE TREATY EXCELLENT DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY FPP TO CONSTRUCT 45 HOUSES ZONING MAP EASTHAM ROAD ZONING LOCATION The site area is designated Objective A2 in Meath County Council’s Development Plan 2013 – 2019 - “to provide for new residential communities and OVERALL OSI MAP SITE PLAN Bettystown is located in the North Eastern corner of community facilities and protect the amenities of existing areas in accordance with an approved County Meath approximately 50 km north of Dublin framework plan”. and 35 km north of Dublin Airport. TOWN PLANNING The entire site has the benefit of a full planning The town is 8 Km south East of Drogheda and is designated as permission (LB/140907) (PL 17.245317) for the a small town in the East Meath Development Plan 2014-2020. DESCRIPTION construction of 45 residential units. The property currently comprises of an regular shaped Phase 2 of the Roseville development consists of 45 The subject site is located along the R150 just a few minutes’ greenfield site extending to approx 2.12 hectares (5.25 acres). dwellings comprising of 18no. 2 storey 3 bedroom walk to Bettystown Beach and adjacent to the Bettystown The property has road frontage on the western side of the site semi-detached houses, 22no. 2 storey 4 bedroom Town Centre which is currently undergoing a huge along the R150 and also benefits from an access through the semi-detached, 1no. 2 storey detached house, and redevelopment. existing Roseville housing development. 4no. 5 bedroom detached houses and all with off There are many excellent amenities in the area including the The lands are currently in grass, have a flat topography and street parking. -

Drogheda Masterplan 2007

3.0 Policy Context 52 Policy Context 3.0 Policy Context 3.1 Introduction a Primary Development Centre alongside other towns in the Greater Dublin Area. The NSS states that the role of There is an extensive range of strategic guidance and Primary Development Centres should take account of policy for land use planning in Ireland. This has been fully wider considerations beyond their relationship with the examined in the preparation of this Report. The following Metropolitan Area, such as how they can energise their section sets out a summary of the overall policy context own catchments and their relationship with neighbouring for the Study Area. regions. A population horizon of 40,000 is recommended for Primary Development Centres to support self- sustaining growth that does not undermine the promotion 3.2 National Spatial Strategy, 2002-2020 of critical mass in other regions. The NSS states that: The National Spatial Strategy (NSS), published in “Drogheda has much potential for development 2002, sets out a twenty year planning framework for the given its scale, established enterprise base, Republic of Ireland, which is designed to achieve a better communications and business and other links with balance of social, economic, physical development and the Greater Dublin Area.” (Chapter 4.3) population growth between regions. It provides a national framework and policy guidance for the implementation of The NSS also recognises and supports the role of the regional, county and city plans. The NSS identifies a Dublin-Belfast Corridor and records Drogheda's position number of 'Gateways', 'Hubs' and 'Development Centres' on that corridor. -

Meath Oral History Collection

Irish Life and Lore Meath Oral History Collection MEATH ORAL HISTORY COLLECTION _____________ CATALOGUE OF 50 RECORDINGS IRISH LIFE AND LORE SERIES Page: 1 / 27 © 2010 Maurice O'Keeffe Irish Life and Lore Meath Oral History Collection Irish Life and Lore Series Maurice and Jane O’Keeffe, Ballyroe, Tralee, County Kerry e-mail: [email protected] Website: www.irishlifeandlore.com Telephone: + 353 (66) 7121991/ + 353 87 2998167 Recordings compiled by : Maurice O’Keeffe Catalogue Editor : Jane O’Keeffe Secretarial work by : n.b.services, Tralee Recordings duplicated by : Midland Duplication, Birr Printed by : Midland Duplication, Birr Privately published by : Maurice and Jane O’Keeffe, Tralee These recordings were made between October and December 2009 This series of recordings was solely funded by Meath County Council Page: 2 / 27 © 2010 Maurice O'Keeffe Irish Life and Lore Meath Oral History Collection NAME: MARK BRADY, NAVAN, BORN 1941 Title: Irish Life and Lore County Meath Collection CD 1 Subject: An emigrant’s story Recorded by: Maurice O’Keeffe Time: 60:49 Mark Brady was recorded while home on holiday in Navan from his work in Mexico. He was born and raised in Flowerhill, Navan, where his parents ran a general grocery business. He describes his initial decision to study for the priesthood and his later decision, after four years study, to follow another path. He worked with his father at the business known as The Golden Goose, and also taught in England for three years. In the 1980s Mark decided to leave Ireland, travel for a while and, when he arrived at Tarahumara in Mexico, enthralled with the place and the people, he decided to stay and do his best to help the people, who were almost destitute. -

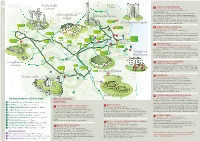

Garden Trail Map 2020

N2 Front cover images L-R: To Belfast, Beaulieu House & Garden, Drogheda Kells High Dundalk and Collon House & Garden, Collon, Co. Louth Carlingford 5 Francis Ledwidge Museum Crosses Janeville, Slane, Co. Meath, C15 DK82 Ardee Tel: +353 (0)41 982 4544 E: [email protected] N33 Drumconrath W: francisledwidge.com M1 World War I poet and soldier, Francis Ledwidge, was born and raised in Old Mellifont this lovingly restored C19th labourer’s cottage, containing memorabilia. Monasterboice The pretty cottage garden reminds us of the poet’s love for nature deep in Abbey the countryside around Slane. Nobber 3 Open: Mar-Oct, Mon-Sun, 10am-5pm. Oct-Mar, Mon-Sun, 10am-3.30pm. N2 Monasterboice N52 Ledwidge Day 26th July 2020. Fee: €3 Adults, €2 Seniors and Students, St Laurence’s Gate €6.50 Family. Please see website for more details. Loughcrew N3 Cairns Clogherhead D St. Peter’s Moynalty Collon 9 6 Killineer House and Gardens Church Drogheda, Co. Louth, A92 P8K7 Tel: +353 (0)86 232 3783 E: [email protected] OOldcastle Old Mellifont R132 Abbey W: killineerhouse.ie 13 Kells Monastic Site Termonfeckin Early C19th spectacular woodland garden with beautiful spring flowering 6 7 shrubs and trees. Formal paths and terraces lead to a picturesque lake and Hill of Slane A R154 Townley Hall Ballinlough Teltown Drogheda summerhouse. House L Francis Museum, I Ledwidg e Baltray Museum Millmount Guided tours of house available on dates below. Groups by appointment. LoughcrewLoLououughcghghc Slane Castle C R163 1 and Martello Open: Feb 1-20, May 1-15, June 1-10, Aug 14-28, Fee: €6 garden. -

Julianstown Architectural Conservation Area Character Appraisal December 2009

Julianstown Architectural Conservation Area Character Appraisal December 2009 Julianstown Architectural Conservation Area Statement Of Character 1 Published by Meath County Council, County Hall, Navan, Co. Meath. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or otherwise, without either the prior written permission of the Publishers or a licence permitting restricted copying in Ireland issued by the Irish Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, The Irish Writers centre, 19 Parnell Square, Dublin 1. All photographs copyright of Meath County Council unless otherwise attributed. © Meath County Council 2009. Includes Ordnance Survey Ireland data reproduced under OSi Licence number 2009/31/CCMA Meath County Council. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Ordnance Survey Ireland and Government of Ireland copyright. Historic maps and photographs are reproduced with kind permission of the Irish Architectural Archive and the Local Studies Section of Navan County Library. ISBN 978-1-900923-21-7 Design and typeset by Legato Design, Dublin 1 Julianstown Architectural Conservation Area Statement of Character Lotts Architecture and Urbanism On behalf of Meath County Council and County Meath Heritage Forum An action of the County Meath Heritage Plan 2007-2011 supported by Meath County Council and the Heritage Council Foreword In 2007 Meath County Council adopted the County Meath Heritage Plan 2007-2011, prepared by the County Heritage Forum, following extensive consultation with stakeholders and the public. The Heritage Forum is a partnership between local and central government, state agencies, heritage and community groups, NGOs local business and development, the farming sector, educational institutions and heritage professionals.