Secrets of the Blue Cliff Record

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhism in America

Buddhism in America The Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series The United States is the birthplace of religious pluralism, and the spiritual landscape of contemporary America is as varied and complex as that of any country in the world. The books in this new series, written by leading scholars for students and general readers alike, fall into two categories: some of these well-crafted, thought-provoking portraits of the country’s major religious groups describe and explain particular religious practices and rituals, beliefs, and major challenges facing a given community today. Others explore current themes and topics in American religion that cut across denominational lines. The texts are supplemented with care- fully selected photographs and artwork, annotated bibliographies, con- cise profiles of important individuals, and chronologies of major events. — Roman Catholicism in America Islam in America . B UDDHISM in America Richard Hughes Seager C C Publishers Since New York Chichester, West Sussex Copyright © Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Seager, Richard Hughes. Buddhism in America / Richard Hughes Seager. p. cm. — (Columbia contemporary American religion series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN ‒‒‒ — ISBN ‒‒‒ (pbk.) . Buddhism—United States. I. Title. II. Series. BQ.S .'—dc – Casebound editions of Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. -

Les Mis, Lyrics

LES MISERABLES Herbert Kretzmer (DISC ONE) ACT ONE 1. PROLOGUE (WORK SONG) CHAIN GANG Look down, look down Don't look 'em in the eye Look down, look down You're here until you die. The sun is strong It's hot as hell below Look down, look down There's twenty years to go. I've done no wrong Sweet Jesus, hear my prayer Look down, look down Sweet Jesus doesn't care I know she'll wait I know that she'll be true Look down, look down They've all forgotten you When I get free You won't see me 'Ere for dust Look down, look down Don't look 'em in the eye. !! Les Miserables!!Page 2 How long, 0 Lord, Before you let me die? Look down, look down You'll always be a slave Look down, look down, You're standing in your grave. JAVERT Now bring me prisoner 24601 Your time is up And your parole's begun You know what that means, VALJEAN Yes, it means I'm free. JAVERT No! It means You get Your yellow ticket-of-leave You are a thief. VALJEAN I stole a loaf of bread. JAVERT You robbed a house. VALJEAN I broke a window pane. My sister's child was close to death And we were starving. !! Les Miserables!!Page 3 JAVERT You will starve again Unless you learn the meaning of the law. VALJEAN I know the meaning of those 19 years A slave of the law. JAVERT Five years for what you did The rest because you tried to run Yes, 24601. -

Contents Transcriptions Romanization Zen 1 Chinese Chán Sanskrit Name 1.1 Periodisation Sanskrit Dhyāna 1.2 Origins and Taoist Influences (C

7/11/2014 Zen - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Zen From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Zen is a school of Mahayana Buddhism[note 1] that Zen developed in China during the 6th century as Chán. From China, Zen spread south to Vietnam, northeast to Korea and Chinese name east to Japan.[2] Simplified Chinese 禅 Traditional Chinese 禪 The word Zen is derived from the Japanese pronunciation of the Middle Chinese word 禪 (dʑjen) (pinyin: Chán), which in Transcriptions turn is derived from the Sanskrit word dhyāna,[3] which can Mandarin be approximately translated as "absorption" or "meditative Hanyu Pinyin Chán state".[4] Cantonese Zen emphasizes insight into Buddha-nature and the personal Jyutping Sim4 expression of this insight in daily life, especially for the benefit Middle Chinese [5][6] of others. As such, it de-emphasizes mere knowledge of Middle Chinese dʑjen sutras and doctrine[7][8] and favors direct understanding Vietnamese name through zazen and interaction with an accomplished Vietnamese Thiền teacher.[9] Korean name The teachings of Zen include various sources of Mahāyāna Hangul 선 thought, especially Yogācāra, the Tathāgatagarbha Sutras and Huayan, with their emphasis on Buddha-nature, totality, Hanja 禪 and the Bodhisattva-ideal.[10][11] The Prajñāpāramitā Transcriptions literature[12] and, to a lesser extent, Madhyamaka have also Revised Romanization Seon been influential. Japanese name Kanji 禅 Contents Transcriptions Romanization Zen 1 Chinese Chán Sanskrit name 1.1 Periodisation Sanskrit dhyāna 1.2 Origins and Taoist influences (c. 200- 500) 1.3 Legendary or Proto-Chán - Six Patriarchs (c. 500-600) 1.4 Early Chán - Tang Dynasty (c. -

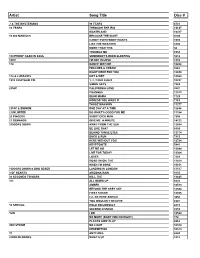

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

And Daemonic Buddhism in India and Tibet

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 The Raven and the Serpent: "The Great All- Pervading R#hula" Daemonic Buddhism in India and Tibet Cameron Bailey Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE RAVEN AND THE SERPENT: “THE GREAT ALL-PERVADING RHULA” AND DMONIC BUDDHISM IN INDIA AND TIBET By CAMERON BAILEY A Thesis submitted to the Department of Religion in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Religion Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2012 Cameron Bailey defended this thesis on April 2, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Bryan Cuevas Professor Directing Thesis Jimmy Yu Committee Member Kathleen Erndl Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For my parents iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank, first and foremost, my adviser Dr. Bryan Cuevas who has guided me through the process of writing this thesis, and introduced me to most of the sources used in it. My growth as a scholar is almost entirely due to his influence. I would also like to thank Dr. Jimmy Yu, Dr. Kathleen Erndl, and Dr. Joseph Hellweg. If there is anything worthwhile in this work, it is undoubtedly due to their instruction. I also wish to thank my former undergraduate advisor at Indiana University, Dr. Richard Nance, who inspired me to become a scholar of Buddhism. -

These Are the Days of Our Lives

These Are the Days of Our Lives 1.1 Synopsis These Are the Days of Our Lives is a four-hour chamber larp scenario about the lives of a group of women friends. It consists of four scenes in which the characters meet up in their late teens, late 20s, late 30s and late 40s. Between these scenes are offgame interludes in which the players choose the life events that they want to have happened to their characters during the ten-year intervening period. The scenario is soundtracked by music of the period appropriate for each scene, which serves as a timekeeper as well as setting underlying mood. The gamesmaster role is primarily that of an offgame facilitator, with minimal intervention during live scenes. The scenario is preceded by a preparatory workshop, and followed by a group debrief. 1.2 Vision The design intention of These Are the Days of Our Lives is for players to explore and experience the drama of real lives. Play should be naturalistic and expressive. It will mix comic and tragic moments, light-hearted enjoyment and serious concern and grief, in the same way that life itself does. The players will be fitting thirty years’ worth of ups and downs – in their characters’ own lives, and in their interrelationships – into a few hours of play, so it will be an emotionally intense experience which may drain or elevate. They’ll be invited to become strongly bonded as a group; and they may have reflections on their own lives as a result of what they’ve experienced in play. -

Mill Valley Oral History Program a Collaboration Between the Mill Valley Historical Society and the Mill Valley Public Library

Mill Valley Oral History Program A collaboration between the Mill Valley Historical Society and the Mill Valley Public Library David Getz An Oral History Interview Conducted by Debra Schwartz in 2020 © 2020 by the Mill Valley Public Library TITLE: Oral History of David Getz INTERVIEWER: Debra Schwartz DESCRIPTION: Transcript, 60 pages INTERVIEW DATE: January 9, 2020 In this oral history, musician and artist David Getz discusses his life and musical career. Born in New York City in 1940, David grew up in a Jewish family in Brooklyn. David recounts how an interest in Native American cultures originally brought him to the drums and tells the story of how he acquired his first drum kit at the age of 15. David explains that as an adolescent he aspired to be an artist and consequently attended Cooper Union after graduating from high school. David recounts his decision to leave New York in 1960 and drive out to California, where he immediately enrolled at the San Francisco Art Institute and soon after started playing music with fellow artists. David explains how he became the drummer for Big Brother and the Holding Company in 1966 and reminisces about the legendary Monterey Pop Festival they performed at the following year. He shares numerous stories about Janis Joplin and speaks movingly about his grief upon hearing the news of her death. David discusses the various bands he played in after the dissolution of Big Brother and the Holding Company, as well as the many places he performed over the years in Marin County. He concludes his oral history with a discussion of his family: his daughters Alarza and Liz, both of whom are singer- songwriters, and his wife Joan Payne, an actress and singer. -

Copy UPDATED KAREOKE 2013

Artist Song Title Disc # ? & THE MYSTERIANS 96 TEARS 6781 10 YEARS THROUGH THE IRIS 13637 WASTELAND 13417 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 9703 CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS 1693 LIKE THE WEATHER 6903 MORE THAN THIS 50 TROUBLE ME 6958 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL SOMEBODY'S BEEN SLEEPING 5612 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 1910 112 DANCE WITH ME 10268 PEACHES & CREAM 9282 RIGHT HERE FOR YOU 12650 112 & LUDACRIS HOT & WET 12569 1910 FRUITGUM CO. 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 10237 SIMON SAYS 7083 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 3847 CHANGES 11513 DEAR MAMA 1729 HOW DO YOU WANT IT 7163 THUGZ MANSION 11277 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME 12686 2 UNLIMITED DO WHAT'S GOOD FOR ME 11184 20 FINGERS SHORT DICK MAN 7505 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE 14122 3 DOORS DOWN AWAY FROM THE SUN 12664 BE LIKE THAT 8899 BEHIND THOSE EYES 13174 DUCK & RUN 7913 HERE WITHOUT YOU 12784 KRYPTONITE 5441 LET ME GO 13044 LIVE FOR TODAY 13364 LOSER 7609 ROAD I'M ON, THE 11419 WHEN I'M GONE 10651 3 DOORS DOWN & BOB SEGER LANDING IN LONDON 13517 3 OF HEARTS ARIZONA RAIN 9135 30 SECONDS TO MARS KILL, THE 13625 311 ALL MIXED UP 6641 AMBER 10513 BEYOND THE GREY SKY 12594 FIRST STRAW 12855 I'LL BE HERE AWHILE 9456 YOU WOULDN'T BELIEVE 8907 38 SPECIAL HOLD ON LOOSELY 2815 SECOND CHANCE 8559 3LW I DO 10524 NO MORE (BABY I'MA DO RIGHT) 178 PLAYAS GON' PLAY 8862 3RD STRIKE NO LIGHT 10310 REDEMPTION 10573 3T ANYTHING 6643 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP 1412 4 P.M. -

Mahayana-Deva. Mahd-Vakya

mahayana-deva. mahd-vakya. 759 a MaJiardraJta (opposed to hSna-ydna), epithet of a later system adh), as, m. paramount sovereign, universal quence, very dignified. (hd-ar), m. of a n. wild = Mahardha of Buddhist teaching promulgated by Nagarjuna, and emperor. Mahd-rdjika, as, pi. epithet am, ginger ( ranardraka). of in the ' class of or reckoned at as, m. a of treated Maha-yana-sutras ; (as), m. having gods demigods (variously 236 (ha-ar), species plant, (commonly J and 220 in of Vishnu. Mahdrbuda n. ten a great chariot,' N. of a king of the Vidya-dharas. number); (as), m. epithet Mahaja.) (ha-ar' ), am, millions. - as, m. an title of Mahd-rdjni, f. a great queen, the principal wife Arbudas = one thousand Mahdnna (hd- Mahayana-deva, honorary c a in her own see Pan. VI. Hiouen-thsang. Mahayana-parigrahaka, as, m. ofa Raja, queen right, reigning queen ; ar), 2, <)O.Mahdrha ( hd-ar), or valuable a follower of the Maha-yana doctrines. Mahdydna- epithet of DargS. Mahd-rdjya, am, n. the rank as, a, am, very worthy deserving, very title ofa or eminent ; prabhasa,N. of a Bodhi-sattva. Mahdydna-yoga- or reigning sovereign, sovereignty. Malid- precious, costly, splendid ; excellent, n. dead of late white sandal-wood. dastra, am, n., N. of a work. Mahdydna-san- rdtra, am, midnight, the night, at (am), n. Malid-lakshmi, is, N. of a work called ma/id- the time after close of f. the Lakshmi the Sakti of N5r5- graha, as, m., ; (also night, midnight, night. great (properly but sometimes identified with yana-samparigraha-s'dstra.) Mahdydna-sTitra, Mahd-rdtri, is, or mahd-rdtrl, f. -

Zen Masters at Play and on Play: a Take on Koans and Koan Practice

ZEN MASTERS AT PLAY AND ON PLAY: A TAKE ON KOANS AND KOAN PRACTICE A thesis submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Brian Peshek August, 2009 Thesis written by Brian Peshek B.Music, University of Cincinnati, 1994 M.A., Kent State University, 2009 Approved by Jeffrey Wattles, Advisor David Odell-Scott, Chair, Department of Philosophy John R.D. Stalvey, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements iv Chapter 1. Introduction and the Question “What is Play?” 1 Chapter 2. The Koan Tradition and Koan Training 14 Chapter 3. Zen Masters At Play in the Koan Tradition 21 Chapter 4. Zen Doctrine 36 Chapter 5. Zen Masters On Play 45 Note on the Layout of Appendixes 79 APPENDIX 1. Seventy-fourth Koan of the Blue Cliff Record: 80 “Jinniu’s Rice Pail” APPENDIX 2. Ninty-third Koan of the Blue Cliff Record: 85 “Daguang Does a Dance” BIBLIOGRAPHY 89 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are times in one’s life when it is appropriate to make one’s gratitude explicit. Sometimes this task is made difficult not by lack of gratitude nor lack of reason for it. Rather, we are occasionally fortunate enough to have more gratitude than words can contain. Such is the case when I consider the contributions of my advisor, Jeffrey Wattles, who went far beyond his obligations in the preparation of this document. From the beginning, his nurturing presence has fueled the process of exploration, allowing me to follow my truth, rather than persuading me to support his. -

AVALOKITESVARA Loka Nat Worship in Myanmar

AVALOKITESVARA Loka Nat Worship in Myanmar A Gift of Dhamma AVALOKITESVARA Loka Nat Tha Worship In Myanmar “(Most venerated and most popular Buddhist deity)” Om Mani Padme Hum.... Page 2 of 12 A Gift of Dhamma Maung Paw, California Bodhisatta Loka Nat (Buddha Image on her Headdress is Amithaba Buddha) Loka Nat, Loka Byu Ha Nat Tha in Myanmar; Kannon, Kanzeon in Japan; Chinese, Kuan Yin, Guanshiyin in Chinese; Tibetan, Spyan-ras- gzigs in Tabatan; Quan-am in Vietnamese Page 3 of 12 A Gift of Dhamma Maung Paw, California Introduction: Avalokitesvara, the Bodhisatta is the most revered Deity in Myanmar. Loka Nat is the only Mahayana Deity left in this Theravada country that Myanmar displays his image openly, not knowing that he is the Mahayana Deity appearing everywhere in the world in a variety of names: Avalokitesvara, Lokesvara, Kuan Yin, Kuan Shih Yin and Kannon. The younger generations got lost in the translation not knowing the name Loka Nat means one and the same for this Bodhisatta known in various part of the world as Avalokitesvara, Lokesvara, Kuan Yin or Kannon. He is believed to guard over the world in the period between the Gotama Sasana and Mettreyya Buddha sasana. Based on Kyaikhtiyoe Cetiya’s inscription, some believed that Loka Nat would bring peace and prosperity to the Goldenland of Myanmar. Its historical origin has been lost due to artistic creativity Myanmar artist. The Myanmar historical record shows that the King Anawratha was known to embrace the worship of Avalokitesvara, Loka Nat. Even after the introduction of Theravada in Bagan, Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva, Lokanattha, Loka Byuhar Nat, Kuan Yin, and Chenresig, had been and still is the most revered Mahayana deity, today. -

The Role of Live Performance in the Gongan Commentary Of

The Role of Live Performance in the Gongan Commentary of the Blue Cliff Record: Reflections on John McRae’s Remarks about a Seminal Chan Buddhist Text Steven Heine Florida International University MCRAE’S REMARKS ON THE TEXT It is widely acknowledged that the Blue Cliff Record 碧巖錄 (Ch. Biyanlu, Jpn. Hekiganroku), a collection in which Yuanwu Keqin (1063–1135) provides various kinds of prose remarks regarding one hundred cases that were originally selected and given poetic comments by Xuedou Chongxian (980–1052), is the seminal Chan Buddhist gongan/kōan 公案 commentary. The text’s innovative discursive structure in relation to its fun- damental religious message concerning the spontaneous yet funda- mentally ambiguous or uncertain quality of Chan enlightenment was a highlight of Song dynasty Chinese cultural and intellectual histori- cal trends. The Blue Cliff Record has long been celebrated for its use of intricate and articulate interpretative devices as the masterpiece or “premier work of the Chan school” 禪門第一書 (or 宗門第一書) that has greatly influenced the development of the tradition for nearly a thousand years since its original publication in 1128. As instrumental and influential as it is regarded, however, theBlue Cliff Record has been shrouded in contention in regard to the value of its approach to the role of language evoked in pursuit of awakening, and it is also clouded by controversy because of legends often accepted uncritically that obscure the origins and significance of the text. This collection is probably best known today for having apparently been destroyed in 1140 by Dahui, Yuanwu’s main disciple yet harshest critic; it is confirmed the collection was left out of circulation before being re- vived and partially reconstructed in the early 1300s.